Finest Hour 190

A Distaff Big Three

January 1, 1970

Finest Hour 190, Fourth Quarter 2020

Page 44

Review by Anne Sebba

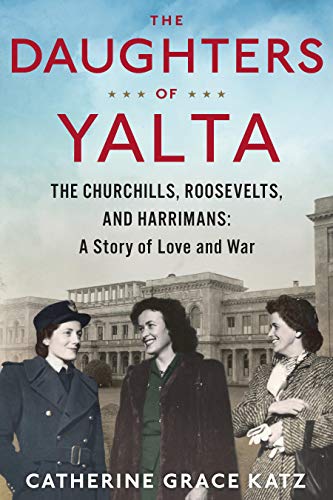

Catherine Grace Katz, Daughters of Yalta, Houghton Mifflin, 2020, 416 pages, $28. ISBN 978–0358117858

Anne Sebba’s latest book Ethel Rosenberg: An American Tragedy will be published in the US and UK in summer 2021.

When Sarah Churchill found herself next to NKVD Chief Lavrenty Beria at a banquet hosted by Stalin at the end of the Yalta Conference, she tried out her best textbook Russian phrases on him, such as “Can I have a hot water bottle please?” In response Beria leered at her and said, with former Soviet ambassador Ivan Maisky translating, “I cannot believe that you need one! Surely there is enough fire in you!”

Sarah, the elegant red–headed daughter of the British prime minister, was unfazed, perfectly able to hold her own with the murderous head of the Soviet Secret Police. So was Anna Roosevelt Boettiger, the thirty-eight-year-old married daughter of the ailing President Roosevelt, who, later at the same dinner, found herself the object of Beria’s attention. Beria, described by Stalin as the Soviet equivalent of Himmler, was trying to get Anna “tight” by ensuring her glass was constantly full for the numerous toasts required. She managed, when no one was looking, to refill her glass with soda water, not vodka.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Such anecdotes pepper this richly detailed book bringing alive one of the most important events in the Second World War. The weeklong Yalta conference, held at a critical moment in February 1945 to discuss the post-War reorganisation of Europe and division of Germany, is often remembered as an occasion when the Soviets, who had insisted on the beautiful Black Sea venue, gained more than did the British and Americans and as such marked the beginning of the Cold War. By seeing events through the tightly focused prism of three daughters of key protagonists—Sarah Churchill (the only one of the three in uniform); Anna Boettiger; and Kathleen Harriman, the vivacious, Russian-speaking ski champion daughter of the US ambassador to Moscow—there is, of course, a danger of making light of such crucial events. That danger is avoided by Catherine Grace Katz in her wonderful debut book.

The daughters of Yalta were linked, in addition to their fathers, by various complicated romantic entanglements, which lent an air of scandal to the diplomatic bag. Kathy Harriman was friends with, and regularly wrote to, Pamela Churchill, the stunningly beautiful British woman, who, in October 1939, had married the wayward, often unfaithful, son of the Prime Minister, Randolph Churchill, with whom she had a son, Winston. Kathy knew also that her father, Averell, had started an affair almost two years earlier with Pamela, almost twenty-eight years his junior. According to Katz, Averell’s reunion at Yalta with Sarah and her father evoked memories of Pamela, “even as he became increasingly burdened with concerns over Stalin’s intentions toward eastern Europe and Roosevelt’s naïveté in his relationship with the Soviet dictator.” Further complications arose as Kathy herself had recently had a brief affair with Anna’s married brother, Franklin Roosevelt Jr., which did not endear her to Anna.

The three women, none of whom was a diplomat, were acting behind the scenes, as they did not attend conference discussions but met with their fathers for lunch (or, in Churchill’s case, brunch) most mornings. Yet, by making use of a wide variety of diaries and letters—some newly released—Katz shows much more than simply what went on behind the scenes. She humanizes history, gives readers an inside view of the many cross-currents working particularly vigorously in February 1945, thus helping to explain how the elderly protagonists failed to show an altogether unified front. It is an original approach since, as Katz points out, “No three women in recent history had acquired such a seat at the table alongside the most powerful leaders in the world at a major international summit.”

Death and illness stalk the story from the start, with the crash of a plane in the sea off Malta just before the conference began, killing several key members of the British delegation on their way to Yalta. On the return journey, Edwin “Pa” Watson, President Roosevelt’s close friend and adviser, died at sea, aged sixty-one. Roosevelt himself was to die just two months later in April 1945. Harry Hopkins, previously the President’s closest adviser since 1931, was seriously ill for most of the conference and found himself marginalised at Yalta by the President’s daughter who, with no political experience, increasingly became her father’s closest confidante and adviser.

The power struggle between Hopkins and Anna is central to the story, because Hopkins was frustrated that Anna was not challenging her father’s poor judgement in his dealings with his allied counterparts. When Hopkins wanted to go home, too sick to work, Roosevelt felt abandoned. Yet Anna, while concluding in her diary that Hopkins was simply too pro-British, nonetheless begged him to stay, believing her father could not write his address to Congress alone, without Hopkins’ help. Hopkins, who had devoted much of his life to assisting Roosevelt, left the ship unceremoniously at Algiers and died in January 1946.

Winston Churchill’s constant preoccupation at Yalta, in addition to preservation of the British Empire, was Polish independence, the issue which had after all brought Britain into the war in September 1939. Churchill quite correctly believed that the Americans did not fully appreciate the significance of the issues involved here, and Harriman himself was aware that his President was not interested in Eastern Europe, since what happened there had very little effect on US domestic opinion. Churchill therefore felt alone on this issue and, in spite of the apparent agreement and success of the conference as the leaders famously smiled for photographers and posterity, it was clear that in reality the Soviet Union would extend its influence in Poland.

Winston admitted to Sarah when she asked after the conference, once on board the Franconia (where she was relieved to find both a hairdresser and chicken sandwiches, and mercifully no more caviar), if he was tired: “Strangely enough, no. Yet I have felt the weight of responsibility more than ever before and in my heart there is anxiety.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.