Finest Hour 190

That Sinking Feeling

April 14, 2021

Finest Hour 190, Fourth Quarter 2020

Page 47

Review by Robin Brodhurst

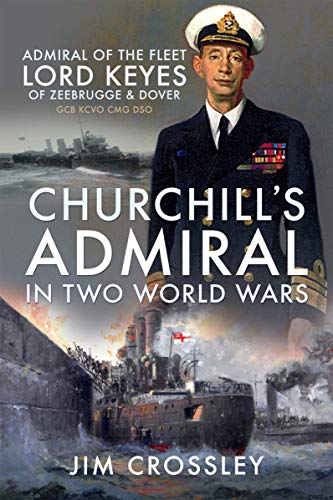

Jim Crossley, Churchill’s Admiral in Two World Wars: Admiral of the Fleet Lord Keyes of Zeebrugge and Dover, Pen & Sword, 2020, 200 pages, £25. ISBN 978–1526748393

Robin Brodhurst is author of Churchill’s Anchor: Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound (Pen and Sword, 2000).

Roger Keyes had an amazing career, involving service in every type of Royal Naval ship and fighting in China, Gallipoli, and the Channel. His bravery was never in doubt, nor was his leadership, which inspired great loyalty among those who served under him. Yet some people hated him. Where Keyes fell down was in the wider aspects of strategic view and political understanding. After a brilliant early career, he was over-promoted. A superb captain and a brilliant commander of small squadrons, both submarines and destroyers, Keyes failed in the roles of fleet commander and Whitehall mandarin.

Keyes’s performance in China in 1900 was symbolic of much that followed: amazing bravery, great leadership, and considerable luck, but also direct disobedience of an order so that he could be in action. Amazingly, he got away with it and received early promotion to commander at twenty-eight. Keyes returned to England a rising star and received command of the Devonport destroyer flotilla, where his leadership skills were very soon evident; he twiced managed to ambush the battleships of the Home Fleet on exercise. In 1910 those same traits were on display when he took command of the Royal Navy’s submarines. His political skills within the Royal Navy, however, began to show their failings. He ran afoul of the Admiralty in general and of First Sea Lord Jackie Fisher in particular.

2024 International Churchill Conference

To get him out of the way, Keyes was appointed chief of staff to the naval force assembling for the Gallipoli campaign in 1915. Like Winston Churchill, Keyes always believed that forcing the Dardanelles would have resulted in Turkey’s surrender. Most historians today would dispute that. Yet Keyes never forgave the political and army authorities who closed down the campaign. He returned to Britain, accepted command of a battleship in the Grand Fleet in June 1916—a month after Jutland—and was promoted Rear Admiral in April 1917.

After a brief stint in London as the first Director of the Plans Division, Keyes was appointed commander of the Dover Patrol in December 1917. This led to the famous Zeebrugge Raid of April 1918. Forever afterwards, Keyes’s name was linked to this episode (he ultimately became Baron Keyes of Zeebrugge), but even his most biased supporters cannot claim that it was a real success. The canal to Bruges was not blocked, and within four days U-boats could pass through it. What the raid did do was to provide a vast propaganda triumph for both Keyes and the Royal Navy. Crossley’s analysis here is good. He accepts the criticisms of Keyes’s plan and its execution, while praising, quite correctly, the admiral’s leadership and personal bravery.

Keyes’ final command was of the Mediterranean Fleet from 1925 to 1928, and here his failings were painfully evident. His lack of political and social antennae resulted in the farcical Royal Oak affair and the evident awareness among most of the fleet that he plainly favoured those officers who played polo. These were not the only reasons, however, why he never became First Sea Lord. The Labour government, which came to power in 1929, was unwilling to appoint an admiral who was more than likely to create a political crisis over disarmament, to which they were committed. Keyes retired as an Admiral of the Fleet and was elected to Parliament in 1934.

In the Second World War, Keyes made a dramatic intervention in the House of Commons during the Norway debate that resulted in Churchill becoming prime minister. Keyes then acted as Churchill’s special representa–

tive to the King of the Belgians, whom he always defended for choosing to stay in Belgium with his people rather than go into exile in England. Keyes bombarded Churchill and the Admiralty with advice and suggestions, as well as demands for a command. Churchill eventually made him Director of Combined Operations in July 1940, where he immediately made enemies of all of the Chiefs of Staff. His plans for operations were impractical, and he expected to be able to command them himself. Churchill was eventually forced to remove Keyes in October 1941. They remained friends.

This short biography has many positive aspects, including a good early history of both destroyers and submarines. There are, though, errors of fact: A. V. Alexander was never a pacifist nor was Dudley Pound “totally unable to stand up to bullying by Churchill.” The bibliography is dated, and there are no citations to guide readers to sources. Despite these failings, I do recommend this book. The life of Keyes is a good lesson for all young officers in how to succeed as a junior officer and in what not to do as a senior one.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.