Finest Hour 190

It Is Finished

The complete official biography.

March 18, 2021

Finest Hour 190, Fourth Quarter 2020

Page 13

Review by Kevin Ruane

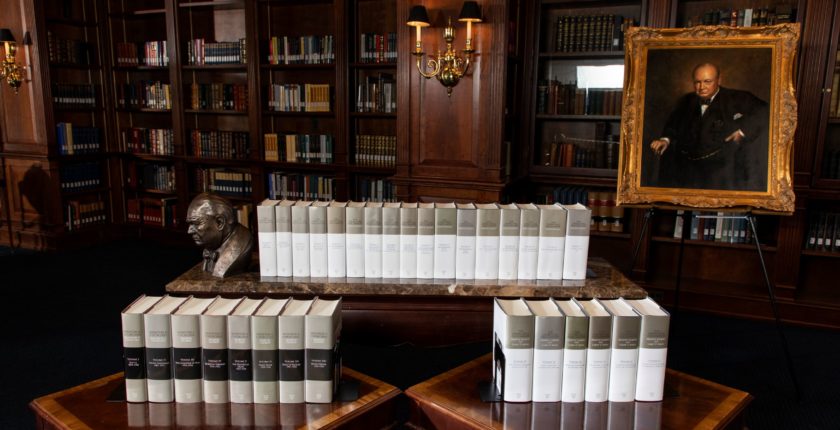

Martin Gilbert and Larry P. Arnn, eds., The Churchill Documents, volume 23, Never Flinch, Never Weary, November 1951 to February 1965, Hillsdale College Press, 2019, 2488 pages, $60. ISBN 978–0916308483

Kevin Ruane is Professor of Modern History at Canterbury Christ Church University and an Archives By-Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge.

The 1951–1955 Conservative government was the only one Winston Churchill formed as a result of winning a General Election. That distinction ought to have earned his administration a hallowed place in his career pantheon. Instead, it is often viewed as an anti-climax. If Churchill’s peacetime government gets any attention in historical surveys or biographies, it is usually as a postscript to the main event, his epic 1940–1945 wartime premiership. Churchill himself is portrayed as aged, ailing, and only spasmodically effective as prime minister before a stroke in 1953 worsened matters. There were occasional flashes of his old brilliance, but the day-to-day grind of peacetime leadership bored him. Having avenged his 1945 electoral defeat, Churchill stands accused in some quarters of doing little with power other than to cling to it. Friends and political intimates initially assumed that he would make way for his anointed successor, the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, within a year. But on he went to April 1955, the fading leader of a government both “undistinguished” and “bad for the country.”1

There is, alas, some truth to all this. Pushing seventy-eightyears-of-age at the time of the 1951 election, Churchill was unquestionably past his prime. The malaise, however, both personal and political, has been exaggerated. Historians specialising in the 1951–1955 period have shown that there was much more to Churchill and his administration than popular-critical memory allows.2 Now, with the appearance of the twenty-third and final volume of The Churchill Documents, the evidence is there for all to see, more than 2,000 pages of it in a massive amplification of Martin Gilbert’s Never Despair (1988), the concluding instalment of the official Churchill biography. The volume’s sub-title, “Never Flinch, Never Weary,” taken from a 1955 Churchill speech, describes perfectly the mind-set required of successive documents-volumes editors Randolph Churchill, Martin Gilbert, and Larry P. Arnn as they went about their Herculean task.

2025 International Churchill Conference

The majority of the documents in this volume come from the Churchill Archives and the United Kingdom National Archives, with a selection of speeches and contemporary political diary extracts adding further colour. There is also interleaving of Churchill family material, ranging from the Winston-Clementine correspondence to letters written by the Churchill children. Peering in through this intimate family portal, readers gain a sense of Churchill as a husband and father, a real feel for the man as opposed to the legend. Still, it is the business of government that bulks largest: here, in a single tome, is a corrective to the popular perception of Churchill’s post-war ministry as inert and ineffective.

On a personal level, Churchill’s greatest achievement in this period was his recovery from his stroke. At the political level, the dovetailing of Documents 23 with Gilbert’s Never Despair reveals a post-stroke Churchill refusing to surrender power, not from hubris but from a genuinely-held conviction that his great experience and renown put him in pole position to achieve two linked goals. The first was to reverse the nuclear arms race before weapons of mass destruction imperilled all mankind. The second goal, born of his fear of the nuclear consequences if Cold War shifted to Hot War, was the convening of an East-West heads of government summit, the first step towards what he hoped would be détente. In the end, Churchill failed in his quest: when he left office in 1955, the Cold War and nuclear weapons still disfigured the international landscape. But as many of these documents attest, his cause was noble, visionary, and praiseworthy.

Foreign and defence policy were Churchill’s favoured spheres of interest, but Documents 23 shows him active across the spectrum of peacetime government: law and order, education, public health, the nationalised industries, and many other issues received his close attention. For its first year, the government’s over-riding concern was a balance-of-payments crisis so severe that Churchill likened it to an economic “1940.” Drastic cuts in public spending were imposed, but the Prime Minister insisted on three exceptions: “Houses and meat and not being scuppered.” In the 1951 election, the Conservatives, noting the slow recovery of Britain’s cities from wartime bombing, pledged to build 300,000 new houses a year. Churchill was convinced that this had been a real vote-winner, and he was keen to honour the promise. Meat, meanwhile, was still rationed as it had been since the war, and it grieved him that the British people were so “shockingly ill fed.” In the event, government and country weathered the storm. By 1953 the economy was stable, by 1954 rationing was gone, and by 1955 the housing programme had hit its overall target.

When Churchill referred to “not being scuppered,” he meant the maintenance of Britain’s international status and interests. Although Documents 23 confirms the eclectic range of Churchill’s activity as premier, the collection is weighted towards documents on foreign, defence, and imperial policy. Churchill’s first paper for the new Cabinet, in November 1951, was on a foreign policy question: European integration. In opposition, Churchill had expressed such fervent public support for the idea of a United States of Europe that many people on the Continent, and even pro-Europeans in his own party, hoped that his return to power would see the UK assume leadership of an already tentatively federalising Western Europe. Churchill’s paper scotched that idea. “We help, we dedicate, we play a part,” he wrote of Britain’s relations with all supranational constructs, “but we are not merged and do not forfeit our insular or Commonwealth-wide character.” This directive ensured that the UK steered clear of the European Defence Community (EDC), a supranational grouping established to facilitate a West German military contribution to collective security. When the EDC collapsed in 1954, Eden, with Churchill’s encouragement, moved swiftly to craft a looser non-federal substitute, the Western European Union (WEU), more in keeping with the government’s preferred approach to European integration.

The WEU provides a good example of Churchill-Eden teamwork; Eden, the skilled diplomatist, fronted the international negotiations while Churchill leant his political throw-weight from the side-lines. It is no secret that Eden was often frustrated and angry with Churchill for denying him the keys to Number 10 for so long, but this should not obscure how effectively the two men worked together, not just on European security but on a host of other international questions. That said, when they disagreed it could be spectacular. Egypt offers a case in point. Here, Churchill’s default imperialism clashed with Eden’s more progressive outlook on Anglo-Egyptian relations. Specifically, Eden wanted to negotiate the withdrawal from Egypt of the 70,000 British troops garrisoning the Suez base, a sprawling complex offering protection to the Suez Canal. Eden hoped to transfer the base to Egyptian authority on the understanding that UK forces could return in an emergency. To Churchill, this was nothing less than “appeasement” of the Cairo government, and he privately sniped about Eden’s “Munich…on the Nile.” It took the emergence of the hydrogen bomb—an awesome weapon of mass destruction far outstripping the atomic bomb—to effect a Churchill-Eden realignment. When, in 1954, British military experts pointed out that the base could be destroyed by a single Soviet H-bomb, Churchill decided that withdrawing UK forces made sense after all.

Mention of the H-bomb brings us back to Churchill’s principal preoccupation. By the start of 1954, both the Americans and Soviets possessed hydrogen weapons. Britain, a mere atomic power since 1952, was left very much exposed to what Churchill called this “new terror.” For some years, the UK had been home to American air bases and nuclear-capable US Air Force bombers, but while Churchill accepted this situation in the spirit of Anglo-American cooperation, the consequence was that Britain was placed “in the very forefront of Soviet antagonism.” In contrast, North America lay safe beyond the operational reach of the current generation of Soviet bombers. In March 1954, the United States tested its biggest ever H-bomb (a 15-megaton monster). On hearing this, a distraught Churchill wrote to President Eisenhower to share his fear that “several million people” in London “would certainly be obliterated” by a comparable Soviet bomb. He added that fall-out, toxic death-clouds radiating far beyond ground zero, was a “peril which marches towards us and is nearer and more deadly to us than to you.”

Churchill was soon channelling his anxieties into a push for a summit at which UK, US, and USSR leaders could begin to work out ways to avoid prestige-engaging showdowns. Meanwhile, recognising that reversing the nuclear arms race was probably impossible, Churchill swung to the other extreme and pioneered the concept we know today as Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). In 1953, he suggested that “when the advance of destructive weapons enables everyone to kill everybody else nobody will want to kill anyone at all.” By 1954 he was persuaded that “equality in nuclear annihilation” between the two Cold War blocs could serve world peace by making war unthinkable. He also began to rein in his previously strong public criticism of the USSR and international communism; in a world of H-bombs, there was no place for ideological extremism, he reflected, only “peaceful co-existence.”

The success of Churchill’s summitry depended on American support as much as on Soviet receptivity. Following Stalin’s death in 1953, his successors in the Kremlin claimed to be interested in easing international tension. Churchill proposed to Eisenhower that Soviet sincerity be tested at a top-level meeting. The President disagreed. “Russia was a woman of the streets,” he maintained, “and whether her dress was new, or just the old one patched, it was certainly the same whore underneath.” Churchill was crestfallen. Nor was his mood improved when, at the start of 1954, the US administration unveiled its so-called New Look national security strategy. Henceforward, nuclear weapons would be America’s primary instrument of deterrence and (if required) retaliation. Intended to alarm America’s enemies, the New Look also scared Churchill.

These simmering tensions in Anglo-American relations boiled over in the spring of 1954 when the Eisenhower administration sought UK participation in a USled military coalition to intervene in Vietnam, where the French faced defeat in their long-running war against the communist Viet-Minh. US strategists saw Vietnam as the “trigger” domino of Southeast Asia, the country whose loss to communism could start a calamitous geo-strategic chain reaction. Appealing directly to Number 10, Eisenhower was confident that Churchill’s pro-Americanism would guarantee UK backing for intervention. What the President did not realise was that the H-bomb, and the nuclear thrust of the New Look, had set the outer limit on what Churchill would do for the “special relationship.” US-led military action in Vietnam would not only invite Chinese counter-intervention, the Prime Minister argued, but would also run a grave risk of thermo-nuclear war with the Soviet Union. There was “a powerful American air base in East Anglia,” he reminded Washington, “and war with China, who would invoke the Sino-Russian Pact, might mean an assault by Hydrogen bombs on these islands.”

British opposition stymied US plans for Vietnam but at some cost to Anglo-American harmony. When the French went on to lose the make-or-break battle of Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, an international conference at Geneva arranged a Vietnam settlement. Eden was the leading figure in the Geneva peace process, with Churchill lending staunch support from London, and the Conservative government’s role in restoring peace to Vietnam (for a time at least) is today recognised as one of its most important achievements.3 The Vietnam crisis also confirmed to Churchill how easily a local-regional problem could escalate into a great power conflict and led him subsequently to redouble his efforts to arrange an East-West summit. Wary of Eisenhower’s negativity, however, Churchill decided to take independent action: in a July 1954 cable sent direct to the Kremlin, he proposed a purely bilateral UK-USSR meeting, in Moscow if necessary.

Unfortunately, Churchill’s initiative quickly backfired. He expected (and duly dealt with) Eisenhower’s displeasure. What he failed to anticipate was the severity of his own Cabinet’s reaction. Ministers were outraged by his failure to consult them in advance and shocked by his flagrant disregard for the sacred principle of collective Cabinet responsibility. For three weeks, the government teetered on the brink of collapse, as Churchill’s backme-or-sack-me ultimatum was met with counter-threats of resignation from several colleagues. Ironically, the government was saved from implosion only by the Kremlin’s rejection of an exclusively Anglo-Soviet meeting. With that, ministerial tempers began to cool, but it had been a chastening experience for a prime minister accustomed to Cabinet fealty.

By the start of 1955, Churchill’s race was almost run. Weary and under renewed pressure from senior party figures to stand down, he set April as his month of departure. To his regret, a summit had still not materialised, while the nuclear stockpiles of the USA and USSR continued to burgeon. Then again, Britain’s stockpile was also poised to expand. Back in June 1954, Churchill and the top secret Defence Policy Committee agreed to the development of a British hydrogen bomb. No matter how much he abhorred weapons of mass destruction, Churchill wanted his country to have the best possible defence, and that meant the H-bomb. In March 1955, he revealed this momentous decision during the course of his last major prime ministerial speech to parliament. Reprinted in this volume, the speech, one of his finest ever, juxtaposed revulsion at the prospect of thermo-nuclear war with hope for the future if all sides in the Cold War came to enjoy approximate nuclear parity. For then, by a “sublime irony…safety will be the sturdy child of terror, and survival the twin brother of annihilation.” It was the perfect statement of Churchill’s MADness.

Churchill lived for almost a full decade after retiring, and the material gathered here faithfully records his final years. As might be expected, there is more family and less politics in these later documents, although Churchill did keep a weather-eye on events at home and abroad (including his successor Eden’s “Suez-ide” in 1956). “The closing days or years of life are grey and dull,” he confided to Clementine in one particularly poignant letter, “but I am lucky to have you at my side.” Readers will be moved by these intimate familial exchanges, but it is in the earlier assemblage of governmental material that this final volume in a project that started nearly sixty years ago makes its real contribution to Churchill studies. Through the tremendous efforts of Larry P. Arnn and his team at Hillsdale College, Churchill’s peacetime administration can no longer be dismissed as insubstantial and inconsequential.

Endnotes

- Simon Heffer, “Why it’s time to debunk the Churchill myth,” New Statesman, 15 January 2015. Andrew Roberts, in his deservedly acclaimed Churchill: Walking with Destiny (2018), allots just thirty of his 1000+ pages to the 1951–1955 government.

- See for example John W. Young, Winston Churchill’s Last Campaign: Britain and the Cold War 1951–55 (1996); Klaus Larres, Churchill’s Cold War: The Politics of Personal Diplomacy (2002); and Kevin Ruane, Churchill and the Bomb in War and Cold War (2016).

- On this claim, see Kevin Ruane and Matthew Jones, Anthony Eden, Anglo-American Relations and the 1954 Indochina Crisis (Bloomsbury, 2019).

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.