Finest Hour 190

Churchill the Dramatist

Siegfried Sassoon in 1915

April 20, 2021

Finest Hour 190, Fourth Quarter 2020

Page 28

By Jonathan Rose

Jonathan Rose is the William R. Kenan Professor of History at Drew University and author of The Literary Churchill: Author, Reader, Actor (2014), from which this article is adapted.

Though he never wrote a play, he might have been a successful playwright. Winston Churchill admired Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw, John Galsworthy, and Noel Coward—and I am convinced that, had he chosen to direct his talents in that direction, he too could have produced well-made West End dramas. We all know that he played with toy soldiers as a boy, but we should also appreciate that he spent endless hours with a toy theatre. Throughout his adult life, he was a frequent and passionate playgoer, and it was in a theatre that he learned his formidable oratorial and performance skills.

But there was more to it than that. It is said that Oscar Wilde’s most memorable character was Oscar Wilde. In a very similar way, Winston Churchill was a stage character brilliantly crafted by Winston Churchill. Of course all politicians (not just Ronald Reagan) are actors, performing in front of audiences for dramatic effect, but Churchill understood the theatre better than most, and thus made himself into a mesmerizing showman.

The Scaffolding of Rhetoric

Like Wilde (who was a good friend of his mother’s), young Winston wrote dissertations on aesthetics. His 1897 essay “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric” laid out the rules for public speaking that we have come to call “Churchill–

ian.” It was clearly written by a student of the drama, applying to politics the techniques he had observed on stage. Short Anglo-Saxon words have more punch than multisyllabic Greek or Latinate terms (one is tempted to scribble in the margin “e.g., blood, sweat, tears”). Naturally “a clear and resonant voice” carries, though “sometimes a slight and not unpleasing stammer or impediment”—like his own lisp—“has been of some assistance in securing the attention of the audience.” Pay attention to rhythm, producing “a cadence which resembles blank verse rather than prose.” In fact, Churchill often wrote out his speeches not in continuous paragraphs, but in something like vers libre. Strive to evoke “a rapid succession of waves of sound and vivid pictures. The audience is delighted by the changing scenes presented to their imagination.” Here the model was cinematic, when the movies were still a very new medium. Victorian melodrama habitually indulged “a tendency to wild extravagance of language—to extravagance so wild that reason recoils.” But, Churchill advised, such hyperbolic pronouncements “become the watchwords of parties and the creeds of nationalities,” and he would deploy them against not only Hitler, but also Lenin, Gandhi, and (in the 1945 General Election) the Labour Party.

2025 International Churchill Conference

So far it might seem that “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric” offers only a bag of tricks to manipulate audiences, but Churchill takes his argument to a higher philosophical plane. Rhetoric, he insists, is more than an “artificial science….The orator is real. The rhetoric is partly artificial. Partly, but not wholly,” for the speaker is genuinely “sentimental and earnest”:

Indeed the orator is the embodiment of the passions of the multitude. Before he can inspire them with any emotion he must be swayed by it himself. When he would rouse their indignation his heart is filled with anger. Before he can move their tears his own must flow. To convince them he must himself believe. His opinions may change as their impressions fade, but every orator means what he says at the moment he says it. He may often be inconsistent. He is never consciously insincere.

To be an effective actor, the speaker must become the part he is playing. Being “earnest” is important, even if it is a matter of artifice. Churchill deconstructed and collapsed the distinction between theatre and reality. In “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric” he was thinking along lines parallel to Oscar Wilde’s “The Decay of Lying.” Both essays presume that “acting naturally” is either impossible or a bore: the human personality must be consciously constructed as a work of dramatic art. Or, as Wilde put it, “Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life,” an epigram that sums up Churchill’s political ideology.

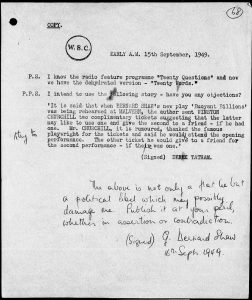

Channeling Shaw

One striking example of Churchill imitating art is from the later phase of the First World War. He was serving as Minister of Munitions, and he shocked his associates by quoting Siegfried Sassoon, a fiercely antiwar poet. Churchill’s brother Jack warned, “I should leave that man alone if I were you. He might start writing a poem about you,” but Winston shot back: “I am not a bit afraid of Siegfried Sassoon. That man can think. I am afraid only of people who cannot think.” He actually invited Sassoon to his London office and offered him a post in the Ministry of Munitions. As Sassoon remembered:

His manner was leisurely, informal, and friendly. Almost at once I began to feel a liking for him….He then made some gratifying allusions to the memorable quality of my war poems, which I acknowledged with bashful decorum. Having got through these preliminaries, he broached—in a goodhumoured and natural way—the subject of my attitude to the war, about which—to my surprise—he seemed interested to hear my point of view. Still more surprising was the fact that he evidently wanted me to “have it out with him.” Overawed though I was, I spotted that the great man aimed at getting a rise out of me, and there was something almost boyish in the way he set about it.

Sassoon was too diffident to rise to the bait, but Churchill was setting up a dramatic dialogue. A general concerned merely with winning the war might consider Sassoon dangerous, but as a student of the theatre Churchill knew that there could be no drama without conflict. He welcomed and needed an antagonist to be his foil. When it became clear that Sassoon declined to engage Churchill in debate, the poet observed:

our proceedings developed into a monologue. Pacing the room, with a big cigar in the corner of his mouth, he gave me an emphatic vindication of militarism as an instrument of policy and stimulator of glorious individual achievements, not only in the mechanism of warfare but in spheres of social progress. The present war, he asserted, had brought about inventive discoveries which would ameliorate the condition of mankind. For example, there had been immense improvements in sanitation. Transfixed and submissive in my chair, I realized that what had begun as a persuasive confutation of my antiwar convictions was now addressed, in pauseful and perorating prose, to no one in particular. From time to time he advanced on me, head thrust well forward and hands clasped behind his back, to deliver the culminating phrases of some resounding period….He now spoke with weighty eloquence of what the Ministry was performing in its vast organization and output, and of what it might yet further achieve in expediting the destruction of the enemy.

There is a logical explanation for this incredible scene. Churchill was reenacting Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara, where Andrew Undershaft, the master of a vast weapons-making empire, persuades the peace-loving poet Adolphus Cusins that he can serve mankind by manufacturing munitions. Churchill saw the play during its initial run and was so impressed that he tried to make Sassoon follow Shaw’s art.

“Betrayal”

With Josef Stalin, Churchill performed one of the most memorable scenes in his classic history The Second World War. When they met in Moscow on 9 October 1944, Churchill briskly set the drama in motion. “Let us settle about our affairs in the Balkans,” he proposed. “Your armies are in Roumania and Bulgaria. We have interests, missions, and agents there. Don’t let us get at cross-purposes in small ways.” He then sketched out on a half-sheet of paper his notorious “Percentages Agreement,” where Russia would get 90 percent of Roumania, Britain 90 percent of Greece, Bulgaria would be split 75 percent Russian and 25 percent British, and so on.

I pushed this across to Stalin, who had by then heard the translation. There was a slight pause. Then he took his blue pencil and made a large tick upon it, and passed it back to us. It was all settled in no more time than it takes to set down….

After this there was a long silence. The pencilled paper lay in the centre of the table. At length I said, “Might it not be thought rather cynical if it seemed we had disposed of these issues, so fateful to millions of people, in such an offhand manner? Let us burn the paper.” “No, you keep it,” said Stalin.

This made no political sense whatsoever. Of course the victorious Allies would have to demarcate occupation zones in liberated Europe, but that would involve extended and detailed negotiations, not some vague fractions scribbled on a scrap of paper. In practical terms, if British and Soviet occupation officers found themselves at loggerheads in Sofia, what would 25% of Bulgaria amount to? The Foreign Office was baffled by the “agreement,” and the War Cabinet demanded to know what the hell was going on. It certainly looked like a blatant act of Great Power imperialism, deciding the fate of millions in an afternoon, so one can understand why Churchill wanted to burn the paper—but then why on earth would he publicize, in a bestselling book, his attempt to destroy the evidence? “I don’t understand now,” recalled US diplomat Averell Harriman, “and I do not believe I understood at the time, just what Churchill thought he was accomplishing by these percentages.” As diplomacy, it was amateurish.

But as theatre, it was brilliant. Read this episode again, but this time treat it as a West End political melodrama, and you will be impressed by Churchill’s stage skills. If the percentages agreement seems simplistic, that was a matter of dramatic compression. A playwright portraying the negotiation of a treaty would of course use some kind of shorthand to summarize it rather than list all the tedious details. Churchill dissolved the boundary between theatre and reality, and to some extent he was more concerned with playing a role than with securing a workable agreement. The role might not be entirely heroic, abandoning small nations to Stalin, but morally problematic actions can rivet the attention of an audience.

In dramatic terms this scene was expertly constructed, a virtual monologue in which the ever-eloquent Churchill beguiles us with his grand bargain. Even more than Harold Pinter, whose most famous play is called Betrayal, Churchill was a master of ominous pauses. There are two in this scene, perfectly timed: one is just a couple of beats, the second is interminable, as the whole cast and audience gaze guiltily at the incriminating paper on the table. The laconic despot has no lines at all—except the mordant curtain line. He quietly waits for Churchill to walk into a trap of his own devising, which is sprung with devastating effect: the playwright understood the impact of a simple silent gesture. And the whole interlude foreshadows terrible (Cold War) conflicts to come.

Melodrama

Churchill’s favorite dramatic genre was melodrama, which dominated the Victorian stage. Here there were none of the moral ambiguities that later marked modernist literature, only a struggle between spotless heroes and depraved villains, in which the former always emerged victorious in the face of insuperable odds. Churchill was especially fond of imperial melodrama, a subgenre set in the colonies, where British soldiers were invariably gallant and the natives fell into two distinct categories. There were good natives: loyal, childlike, incapable of self-government, and properly grateful for British rule. They were oppressed or misled by wicked natives, defined as those who resisted the British. That goes a long way toward explaining Churchill’s diehard imperialism: in his mind, Mohandas Gandhi was obviously a wicked native.

Churchill once considered writing a stage melodrama about the Boer War, but his mother dissuaded him. She recognized that, after all the British reverses and troubling moral questions surrounding the conflict, the public was no longer in the mood for patriotic stage posturing and flag-waving. Melodrama was finally killed and buried amidst the holocausts of the First World War. As Ernest Hemingway put it in A Farewell to Arms, “Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the Dates.”

Churchill had written a melodrama of his own: his 1899 novel Savrola. It is arguably the worst novel of the nineteenth century, but even awful literature can reveal much about the mind of the writer, and Savrola turned out to be a remarkable prophecy. It tells the story of a brilliant author and public speaker who uses his wonderful oratorical powers to defeat the evil dictator of a Middle European country, a dictator who tears up treaties, stabs his political rivals in the back, murders prisoners of war, does not hesitate to use torture, and recklessly seeks an armed confrontation with the British Empire. Historians have long struggled to explain why Churchill, who was wrong about so many things, was right about Adolf Hitler from the very beginning. Once again, Churchill’s politics followed his literary imagination. He immediately recognized and resisted Hitler because the Führer so closely resembled the melodramatic villain he had created thirty years before.

Claptrap

In every melodrama there is a scene, as the play approaches its climax, where the hero seems to face inevitable defeat. But rather than capitulate, he delivers a fervent oration, proclaiming what he is fighting for, and hurling defiance in the face of the villain. This performance naturally obliges the audience to applaud furiously: they are fairly trapped into clapping, and therefore this hoary stage device was called “claptrap.” Here is an example that may be familiar to you: “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender….”

The general disillusionment that followed the First World War seemed to render melodrama hopelessly obsolete. After the Somme, how could anyone believe in simple heroes or villains? But by 1940 the British people were actually confronting absolute evil. The moral clarity of melodrama had returned. Churchill was the only British leader who had written a melodrama, and only he could stage a performance that roused the old Victorian stage passions. As a soldier who narrowly escaped from Dunkirk recalled:

the Nazis kicked my unit to death. We left everything behind when we got out; some of my men didn’t even have boots. They dumped us along the roads near Dover, and all of us were scared and dazed, and the memory of the Panzers could set us screaming at night. Then he got on the wireless and said that we’d never surrender. And I cried when I heard him….And I thought to hell with the Panzers, WE’RE

GOING TO WIN.

That was precisely the effect that claptrap is designed to produce on an audience, and Churchill had just delivered the finest claptrap ever uttered.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.