Finest Hour 190

Winston Churchill, Meet Winston Churchill

A novel by the American Churchill

March 18, 2021

Finest Hour 190, Fourth Quarter 2020

Page 17

By Ronald I. Cohen

Ronald I Cohen MBE is author of A Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill (2006).

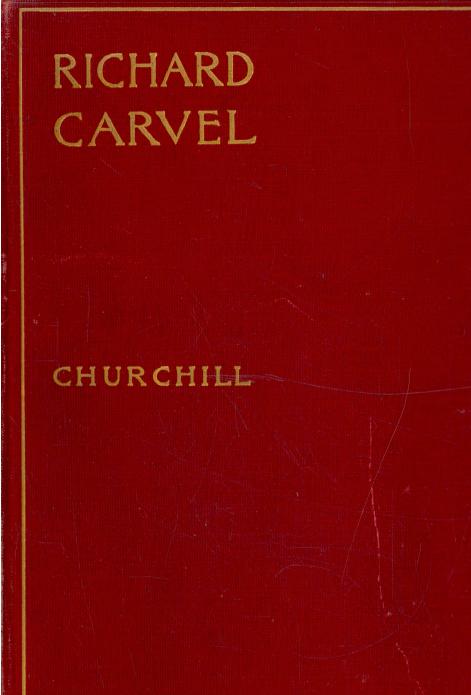

Collectors of Churchill books have inevitably run into offers of volumes by Winston Churchill with unfamiliar titles such as Coniston, Richard Carvel, and Mr. Crewe’s Career. One title looks close to familiar, The Crisis, but not quite right. You can find online listings for it today by British booksellers attributing authorship to “Sir Winston Churchill.” A little fact checking by prospective purchasers or half-diligent booksellers, however, will reveal that The Crisis and the other three titles were all produced by an American author named Winston Churchill and not the British Winston Churchill to whom this journal is dedicated.

The two Winston Churchills did have connections in terms of age and avocation. The American Winston was born in 1871, just three years before the British Winston. Both Winstons became well-known writers in the late 1890s, albeit continents and subject areas apart. In My Early Life (published in 1930), British Winston explained how he became aware of the American novelist.

In the spring of 1899 I became conscious of the fact that there was another Winston Churchill who also wrote books; apparently he wrote novels, and very good novels too, which achieved an enormous circulation in the United States. I received from many quarters congratulations on my skill as a writer of fiction. I thought at first these were due to a belated appreciation of the merits of Savrola. Gradually I realised that there was ‘another Richmond in the field,’ luckily on the other side of the Atlantic.

2024 International Churchill Conference

In fact, in the late 1890s, the American Winston, a native of Vermont, was far better known as an author than the upstart British cavalry officer with whom he shared a name. While The Celebrity (published in 1898) attracted some favourable attention, American Winston’s Richard Carvel (published in 1899) achieved an immense success. Two million copies were sold in a nation of just seventy-six million people at the time. The accrued revenues made the author a rich man. His next two works, The Crossing (1901) and The Crisis (1904), both rose to the top of the American fiction best-seller lists.

In 1898 and 1899, the British Winston Churchill had also produced two works, one non-fiction (The Story of the Malakand Field Force) about a military campaign on India’s North-West Frontier, and the other fiction (Savrola), which was being serialised in Macmillan’s Magazine. Savrola was published in volume form soon thereafter in February 1900 and would be British Winston’s only book-length work of fiction. He was, however, on the verge of publishing four volumes about his military campaigns in Africa, which he did between November 1899 and October 1900.

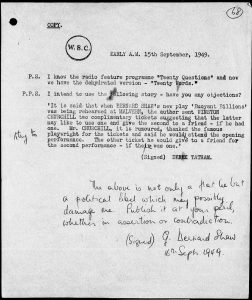

With so much literary activity between the two Winstons, confusion among the reading public looked to be problematic. British Winston took action. On 7 June 1899, he wrote his American counterpart of the “grave danger of his [own] works being mistaken for those of [the other] Mr. Winston Churchill.” Two weeks later, American Winston replied in a similar vein, and a “deal” was done. Henceforth, British Winston would be identified in his writings as “Winston Spencer Churchill” and the American novelist as plain “Winston Churchill.” First published in September 1930 in the English News Chronicle and a month later in My Early Life, this exchange of letters has become a classic (see page 20).

Mr. Winston Churchill Meets Mr. Winston Churchill

Following his first election to Parliament and an extremely successful lecture tour in the United Kingdom on “The War as I Saw It,” British Winston sailed for the United States on 1 December 1900 to continue his lucrative lecturing in North America. In New York, he was greeted by his agent, Major J. B. Pond [see FH 174], and met Vice-President Elect (and incumbent Governor) Theodore Roosevelt, as well as Governor-Elect Benjamin Odell and Mayor Robert Van Wyck. As part of his lecture tour, British Winston spoke at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City, where hewas introduced by Mark Twain.

After speaking appearances in Philadelphia, New Haven, Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, British Winston arrived in Boston on 17 December. His first stop was the post office, at which he meant to collect mail that should have been forwarded to him from elsewhere. No mail. Understandably the post office, seeing the name of a famous Bostonian resident, routed all such mail to the Back Bay Post Office, which served the American Winston’s house at 181 Beacon Street. In the circumstances, since his mission to collect his correspondence had failed and he was ailing, British Winston went directly to the Hotel Touraine, where he was staying, in order to rest since he had to perform that evening. Meanwhile, Major Pond went to the American Winston’s home to recover his client’s mail. No luck in that quest either, since there had not yet been time for the redirected mail to be delivered.

Major Pond, likely reluctant to return to his client with nothing to show for his trip, brought the American author back with him to meet the British Winston. The Baltimore Sun reported the following day on Pond’s brief introduction of the two Winstons:

The young, slender, lighthaired Englishman was in bed at his room at the Touraine shortly after noon, when his lecture manager, Major J. B. Pond arrived with the heavily-built, six-foot American author, smooth shaven, dark complexion, having merry black eyes and with his stout form encased in a Raglan of dark gray.

“Mr. Churchill, Mr. Churchill,” said the Major. The man on the bed turned over on his side and held out his hand.

“I’m sorry to find that you are ill,” said the Churchill in the Raglan as he caught the outstretched hand.

“Nothing serious, I guess” said the other. “Been travelling, you know; but, I say, how came you by that name?”

The author of Richard Carvel smiled. “It seems that there have been Winston Churchills over here for a good many years,” he replied.

The two Winstons spoke briefly, determining, among other things, that they had no ancestors in common. The Boston Globe’s account of the historic moment, otherwise similar to that of the Sun’s, ended with an understatement: “It was an odd meeting.”

In any case, the two Winstons arranged to meet for lunch about an hour later in the Dutch Room of the hotel, where they spoke at greater length. The Baltimore Sun reported that “there was a running fire of talk all the time” during which the two authors discovered that they both were interested in public affairs. After lunch, the two Winstons walked through the nearby Boston Common. As they chatted, British Winston suggested to his American homonym that he should go into politics, explaining, “I mean to be Prime Minster of England: it would be a great lark if you were President of the United States at the same time.”

American Winston’s Political Career

There is no record of how American Winston replied to British Winston’s suggestion, but he did subsequently run for and was elected to the New Hampshire House of Representatives, where he served from 1903 to 1905. He then attempted to secure the Republican nomination for governor of New Hampshire in 1906. In a front-page article entitled “Watch the Winstons,” the 9 August 1906 edition of New York Times picked up the trans-oceanic leadership theme laid out by the Daily Sketch the day before:

Here is Lord Randolph Churchill’s son at one and thirty the most striking and picturesque figure in the Liberal Party—a potential Premier. Across the water is his cognominal double, a man of 34, aiming at a post which is a step upon the way of a man whose goal is the Presidency.

Alas, American Winston lost the race. In 1912 he was nominated as Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive party candidate for governor—and lost again. Thus ended American Winston’s political career.

British Winston’s Boston Success

After the walk of the Winstons on Boston Common, British Winston returned to his room to prepare for his talk that evening at the Tremont Temple. The lecture was a great success. The Boston Herald stated that his lecture “drew to Tremont Temple one of the largest audiences ever seen within that edifice,” while the Boston Globe reported that “the audience was dressy, largely of British sympathies, and thoroughly enthusiastic.” Their several decks of headlines read: “Correspondent Warmly Greeted at Tremont Temple,” “Makes a Good Impression on Large Audience,” and “South African Experiences Interestingly Told.”

Following the lecture, the “well-known” American author, as the Globe described him, under the headline “WINSTON DINES WINSTON SPENCER,” arranged a dinner for the speaker at the Somerset Club, “where they made up a merry party, the affair being strictly informal. Nearly all of those present attended the lecture earlier in the evening and were charmed with Lieut. Churchill’s modest story of his many escapes while en route from Pretoria to the coast.” The one glitch in the proceedings was recounted many years later by British Winston in My Early Life:

He [American Winston] entertained me at a very gay banquet of young men, and we made each other complimentary speeches. Some confusion however persisted; all my mails were sent to his address and the bill for the dinner came in to me. I need not say that both these errors were speedily redressed.

The Winstons Separate

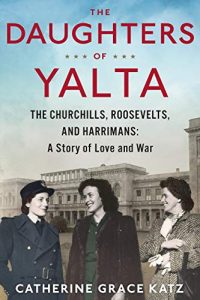

Sadly, the very positive and promising day in Boston was never repeated. Although the last sentence of the Baltimore Sun report of the meeting of the two Winstons was, “They have promised to cultivate each other’s acquaintance,” it never happened. There was no further correspondence, and they never again met in person. Even when the American Winston was interviewing leading statesmen in London during the First World War while researching his only work of non-fiction, A Traveller in War-Time (published in 1918), he did not trouble to seek out Winston Spencer Churchill. In fact, the American Winston stopped writing and withdrew from public life entirely in about 1919. When he died in Winter Park, Florida in 1947 at the age of seventy-five, American Winston was long since a forgotten figure in his own country. Nevertheless, the obituary writer for the New York Times observed that “In 1900, even after the British Churchill had been taken prisoner by the Boers and dramatically escaped, there was no question in this country as to which Churchill was the Winston Churchill.”

Today the brief connection between the two Winstons remains crystallized in their brilliant correspondence of June 1899, their Boston meetings of December 1900, and perpetual confusion in the second-hand book market. Sic transit gloria Churchillorum.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.