Finest Hour 190

Two Winston Churchills

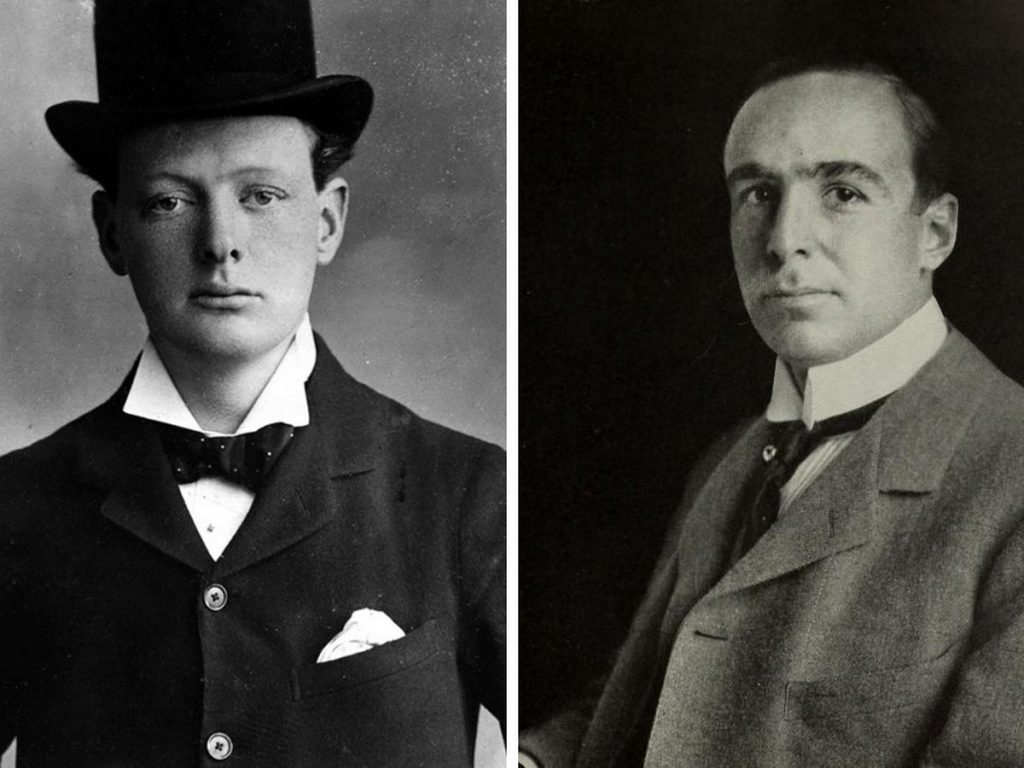

The two Winston Churchills

March 18, 2021

Finest Hour 190, Fourth Quarter 2020

Page 21

By Lawrence J. Siskind

Lawrence J. Siskind is of counsel at Coblentz Patch Duffy & Bass LLP in San Francisco, where he specializes in intellectual property law.

Although perhaps best known to history as the man who stood up to Hitler, Winston Churchill, journalist, warrior, and statesman, also made great contributions to American trademark law. Indeed, Churchill was a pioneer and one of the first proponents of trademark coexistence agreements.

Trademark coexistence agreements are peace treaties under which the owners of similar marks agree to forgo war and to divide the marketplace instead. The division may relate to goods, with one owner, for example, using its mark on raisins while the other uses its similar mark on oranges. The boundary may be geographic, allowing one party to market products on the West Coast while the other markets on the East Coast. Or the division may involve incorporating subtle distinctions in the marks themselves.

In the case of Churchill—while certainly more modest than saving civilization from Nazi conquest—his major contribution to trademark law involved a trademark dear to his heart: his own name.

2025 International Churchill Conference

A Tale of Two Churchills

In the preceding article, Ronald I. Cohen has described the confusion that developed when Churchill discovered in the spring of 1899 that there was an American author also named Winston Churchill who was busy publishing books.

This “American Winston Churchill” was indeed a successful author and a formidable fellow in his own right. At the Naval Academy, he had been a storied fencer and had captained the eight-oared crew. After graduation, he became editor of Cosmopolitan before leaving that post to devote himself full time to writing novels. He also harbored ambitions to run for elected office and later did so in New Hampshire. Suffice it to say that when the British Churchill became aware of the American Churchill, the two young men were on an equal footing, with comparable literary achievements and political aspirations.

The British Churchill immediately recognized that he faced a trademark problem. He was keen to lecture and promote his books in the American market, and he was aware of the public confusion caused by the two men engaging in similar activities under the identical “Winston Churchill” mark. Suing the American Churchill was not an option since, in the United States at least, the American Churchill had priority and superior rights to the mark.

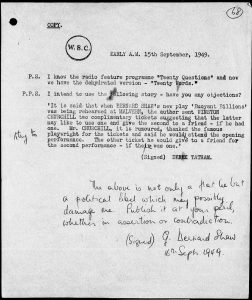

The British Churchill’s solution was to initiate the exchange of letters reprinted on the facing page. Here was a coexistence agreement based neither on products (both Churchills were in the business of producing literary works) nor on geography (both Churchills catered to an Anglo-American market) but on the marks themselves. The proposed addition of “Spencer” to his pen name, in the British Churchill’s view, would create a different commercial impression sufficient to allay public confusion. The courteous American Churchill went his British namesake one better, when he offered to insert the words “The American” after his name on the title-page of his books.

Although no formal coexistence agreement was drawn up, the British Churchill considered the matter well ended since the parties had agreed in principle. “All was settled amicably,” he wrote in My Early Life, “and by degrees the reading public accommodated themselves to the fact that there had arrived at the same moment two different persons of the same name who would from henceforward minister copiously to their literary, or if need be, their political requirements.”

Fast Fade

Despite the best intentions of the parties, the Winston Churchill coexistence agreement faded into irrelevancy over time. The British Churchill made only a partial effort to comply with his commitment to include “Spencer” in his mark. He reduced the name to its initial, and “Winston S. Churchill” became his nom de plume. If the American Churchill objected to this as a breach of the agreement, he never said so. For that matter, the American failed to follow up on his idea of inserting the words “the American” in the title pages of his books.

But the main reason the Winston Churchill coexistence agreement withered was, of course, the growing disparity in fame between the two trademark holders. Within a few years of the agreement being made, the British Churchill was experiencing a meteoric rise in politics. The American Churchill’s political career, by contrast, barely got started before it permanently fizzled out.

The disparity also extended to their literary careers. Despite the distraction of politics, the British Churchill’s writing production was prodigious, estimated to total some twenty million words. His history of The Second World War alone weighs in at 1.6 million words, not counting appendices. The American Churchill’s writing career, meanwhile, came to an end in 1919 when he withdrew from public life to contemplate religion. He died in 1947 before his British counterpart had published even the first of his six volumes of war memoirs.

The confusion between the two holders of the Winston Churchill mark has lingered. If it still confuses book sellers and buyers today, they may be comforted to know that more than a century ago it also upset Theodore Roosevelt, a longtime friend of the American Churchill, who harbored a very different opinion of the British one. Shortly after the two Churchills met in Boston in 1900, the British Churchill took a train to Albany to dine with TR, who was then Governor and Vice President-elect. Churchill did not make a positive impression. “I saw the Englishman, Winston Churchill,” Roosevelt noted to a friend. “[H]e is not an attractive fellow.”

In 1909, while on a hunting trip in Africa, the then former President Roosevelt wrote a long letter in pencil to his friend Senator Henry Cabot Lodge. Among other topics, Roosevelt referred to novelists whose works were available on that continent. He mentioned the name Churchill then quickly added: “I mean of course, our Winston Churchill, Winston Churchill the gentleman.”

Coexistence agreement or not, at least one member of the public was not confused as to which Churchill was which, and he was determined to do all he could to prevent confusion among others.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.