Finest Hour 194

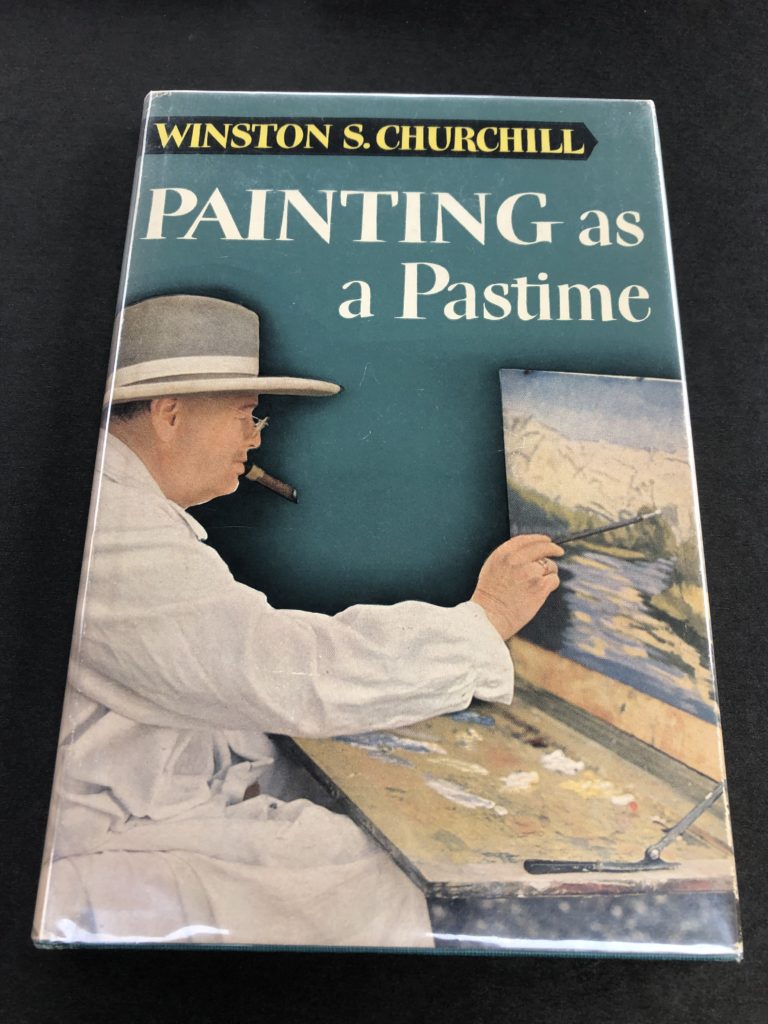

Sir Winston Churchill’s Painting as a Pastime

First US edition - McGraw-Hill

September 28, 2022

Finest Hour 194, Fourth Quarter 2021

Page 33

By Ronald I. Cohen

Ronald Cohen CM MBE is author of Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill (2006).

This article is not the place to explore what drew Churchill to painting in 1915 in that difficult period in the First World War when he left the Cabinet. Others in this issue tell that story. My goal is to tell how and where Churchill himself wrote about that hobby.

The first inkling of the possible publication of that story came in a letter from Winston to Clementine on 6 February 1921. Further to discussions he had obviously had previously with the Strand Magazine, he reported to her that the monthly would “accept my terms & will pay £1,000 for two articles with pictures reproduced in colour. As this will not be subject to Income Tax, it is really worth £1,600. So the painting has paid for itself, & a handsome profit over.”1

Clementine’s initial reaction was hesitant. Four days later, she asked Winston: “Would it not be possible to reproduce your pictures but for someone else to write the Article.” She was concerned that “the professionals would be vexed & say you do not yet know enough about Art” and that “[t]he danger there seems to me that either it may be thought naïf or conceited.” That said, she was enthralled by the terms:

2024 International Churchill Conference

I am as anxious as you are to snooker that £1,000, & as proud as you can be that you have had the offer; but just now I do not think it would be wise to do anything which will cause you to be discussed trivially as it were. If there is to be an argument let it be as to whether you are going to be a good ‘Imperial Minister’ or not.2

On 14 February, he replied to Clementine’s points: “All that you say about the article on painting I will carefully consider. There is nearly a year before it will appear and it will be the only one I shall write. It is quite unconnected with politics and therefore not open to any of the objections which have been urged against others.”3

The decision was taken to accept the terms of the Strand and the article was published in two parts in December 19214 and January 1922.5 While there have been subsequent appearances of the essay (about which more below), this is the only publication that begins with the following words:

I do not submit these sketches to the public gaze because I am under any illusion about their merit. They are the productions of a week-end and holiday amateur who during the last few years has found a new pleasure, and who wishes to tell others of his luck.

The essay was published, with or without reproductions, in periodical form in a condensed version in Reader’s Digest in 1933, then again in the reduced format in the Strand Magazine in 1946, and finally in the Saturday Evening Post in 1972. More importantly, the two parts were collected for the first time in volume form in the Earl of Birkenhead’s The Hundred Best English Essays in November 1929 and then in 1932 in Churchill’s own Thoughts and Adventures as the final two chapters, “Hobbies” and “Painting as a Pastime.”

The first suggestion that the essay merited separate, standalone publication was made in curious circumstances in 1945. At that time, Churchill’s publisher in the United States was Little, Brown. The Boston firm began their relationship with Churchill’s second volume of war speeches, The Unrelenting Struggle. It ended with the sixth volume, Victory, in 1946. Perhaps enthusiastic, however, about three printings of The Dawn of Liberation in a single month (August 1945), Raymond Everitt of Little, Brown sent a proposal to Churchill on 25 October 1945. Although Everitt was clearly unfamiliar with the existence of a Churchillian essay on painting, the firm was aware that Churchill was a painter. Accordingly, he wrote:

As publishers of your speeches since 1942, we would like to make a suggestion for a book by you. We should like to publish for you reproductions of a selection of your water colors, with perhaps a short text by you on amateur painting or amateur art. While we are not a bit sure that there would be a large audience in this country, we should be proud to do it and would go out of our way to get first-rate colour reproductions. Naturally, we would not urge you to let us publish it unless you thought it would be amusing to do and that you’d like that kind of record in book form. Please let us have some word at your convenience.6

I expect that, among other issues, Churchill would have been annoyed at Everitt’s ignorant reference to the Prime Minister’s “water colors.” Oils were his medium, not water-colours. As he wrote in Painting as a Pastime: “I write no word in disparagement of water-colours. But there really is nothing like oils. You have a medium at your disposal which offers real power, if only you can find out how to use it. Moreover, it is easier to get a certain distance along the road by its means than by water-colour.”

By separate letter of the same date to Aubrey Gentry of Cassell (a copy of which had also been sent to Sir Newman Flower) Little, Brown informed the British publisher that they had approached Churchill directly on the subject and they hoped that “you may like the idea and, if Mr. Churchill is willing to do it, we wish you would take the English end of the project.” Since they projected that “production expenses [would] be heavy,… we should not look forward to a large advance.” On 13 November, Churchill’s private personal secretary Jo Sturdee responded that “Mr. Churchill…does not wish to avail himself of your offer to publish some of his paintings in colour reproduction at the present time.” Sir Newman Flower wrote bluntly to Raymond Everitt on 10 January 1946. He said that Churchill

made it quite clear to me that there was “nothing doing”….I mentioned the matter to him again when I saw him two days before he left England, and he made it quite clear that all arrangements which he wished to make regarding these pictures had been long since completed.

There will be a very interesting book by him a little later, of which we shall give you the offer. I will let you know about this in due course.7

In the event, of course, neither the British nor the American firm became the publisher of the stand-alone edition of Painting as a Pastime.

By 1947, Churchill’s British publisher was firmly Odhams, which then held the copyright in Churchill’s pre-1940 works. In that year, they published new editions of My Early Life, Thoughts and Adventures, Great Contemporaries, and Step by Step. They were, therefore, logical contenders to publish the next Churchill oeuvre, which was the first separate edition of Painting as a Pastime, released in December 1948.8 It was published in an impressive 25,000 copies. Odhams reprinted the book in June 1949 (12,000 copies), in October (20,000 copies), and then again in 1962, and twice more in 1965.

Odhams made arrangements for publication in the United States by McGraw-Hill. To do so, they needed to clear the American rights with Scribners, which held the copyright in Amid These Storms.9 Although permission had apparently been granted in December 1947 against payment of $150, prior to the publication of the Odhams/Ernest Benn first edition, Odhams cabled back on 17 June 1949 to ensure that that permission still availed. Scribner’s replied that the sum was inadequate:

AT TIME DID NOT UNDERSTAND OUR CHURCHILL CHAPTERS COMPRISED ENTIRE TEXT PAINTING BOOK STOP UNDER CIRCUMSTANCES BELIEVE WE SHOULD RECEIVE FIVE CENTS ROYALTY AMERICAN SALES10

Odhams responded the following day:

THANKS CABLE CHURCHILL PAINTINGS STOP OUR COSTS PAINTING AS A PASTIME ISSUE NO. 194 | 35 AND QUOTATIONS BASED ON YOUR PREVIOUS OFFER BUT SUGGEST OUTRIGHT PAYMENT FEE SEVEN FIFTY DOLLARS OR ROYALTY THREE CENTS UNITED STATES SALES STOP OUR MARGIN VERY SMALL AND FEEL WE MUST STAND BY QUOTATIONS GIVEN PLEASE CABLE

On the next day, Scribners accepted:

CHURCHILL PAINTINGS ACCEPT YOUR OFFER OUTRIGHT PAYMENT SEVEN HUNDRED FIFTY DOLLARS

C. L. Shard, Odhams’s Book Department Manager, cabled on 4 July to acknowledge the arrangement and to advise of the American publishing deal they had arranged:

THANKS CABLE CHURCHILLS PAINTINGS SEVEN HUNDRED FIFTY DOLLARS OUTRIGHT AGREED STOP ARRANGED UNITED STATES EDITION WITH MCGRAW HILL AND ARE SHIPPING SHEETS

The McGraw-Hill issue was published in February 1950. It is also known (as early as April 1950) as a Whittlesey House publication, which is a trade-book imprint of McGraw-Hill. It went out of print in 1958.

Once sales of the McGraw-Hill issue were exhausted, the rights to the American edition reverted to Odhams. Its head, G. C. Piper, reverted to Scribners regarding the American rights, as they were interested in the marketing of a paperback edition in the United States. He added an interesting observation:

I take leave to doubt whether the issue of the original edition of PAINTING AS A PASTIME by McGraw-Hill adversely affected to any extent the sale of AMID THESE STORMS. We found that it had no effect on our edition of THOUGHTS AND ADVENTURES because, I think, people bought the book for the pictures and not the text.

The arrangement was confirmed, and the Cornerstone Library published the paperback in 1961. It was followed by second, third, and fourth printings in 1965 and 1966. Cornerstone also issued a cased version in 1965, perhaps wishing to piggyback on the recent death of Sir Winston.

Translations of the book were published in 1950 in Finnish, French, and German and subsequently in Japanese and Spanish.

Just days before Churchill’s ninetieth birthday on 30 November 1964, Penguin Books published a paperback edition in England. Second and third printings occurred in 1965 and 1968. A limited edition (500 copies) of Painting as a Pastime was published in San Francisco in October 1985 by Gump’s Department Store in honour of an exhibition, “British Style,” then occurring at the luxury retailer. All these copies were signed by Churchill’s grandson, Winston S. Churchill MP.

The final separate edition of this evocative essay on Churchill’s inspiring pastime was published by Levenger Editions of Delray Beach, Florida on 26 June 2002. It includes a new Foreword by daughter Mary Soames, in which she concludes: “I believe this compelling occupation played a real part in renewing the source of the great inner strength that was his, enabling him to confront storms, ride out depressions, and rise above the rough passages of his political life.”

Endnotes

1. Martin Gilbert, ed., The Churchill Documents, vol. IX, Disruption and Chaos, July 1919—March 1921 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2010), p. 1333.

2. Mary Soames, ed., Speaking for Themselves: The Personal Letters of Winston and Clementine Churchill (London: Doubleday, 1998), pp. 227–28.

3. Gilbert, p. 1352.

4. At pp. 535–44, with reproductions of eleven of his paintings, and prominent promotion of the article on cover of the ‘Christmas Number’ of the issue, with the title first announced as “Painting as a Pastime.”

5. At pp. 13–20.

6. Ronald Cohen, Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill (London: ThoemmesContinuum, 2006), vol. I, pp. 871–72.

7. Ibid., p. 872.

8. Under the combined imprint of Odhams and Ernest Benn, whose role in the production and marketing of the book is unknown.

9. The title of Thoughts and Adventures in the United States.

10. These cables are from the Scribner Archives, C0101, Author Files III, Box 12, folder 9.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.