Finest Hour 194

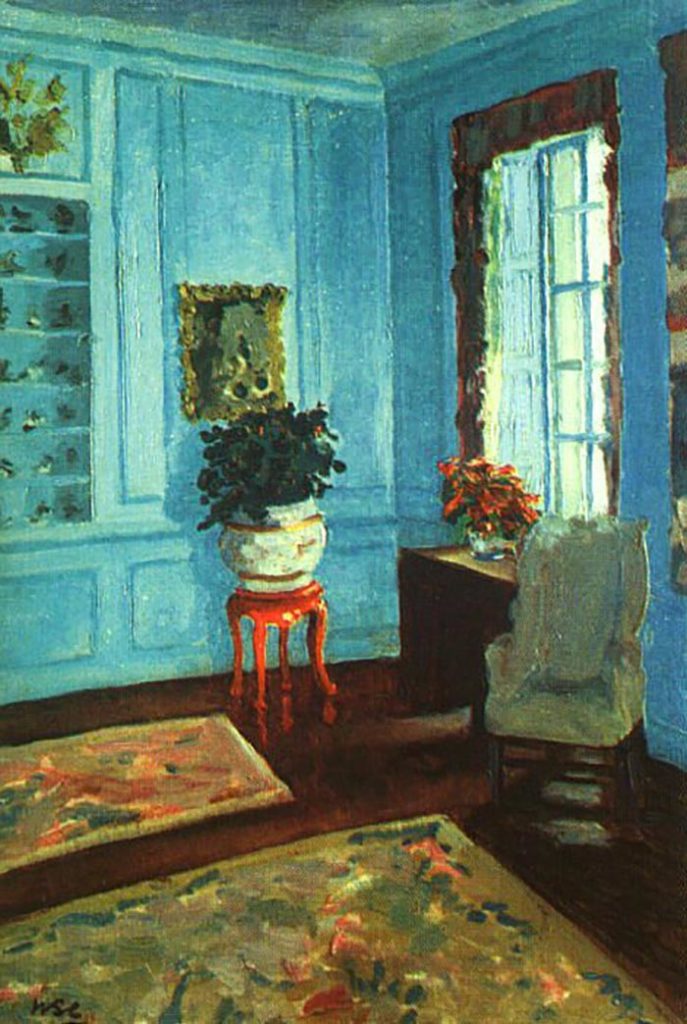

Brazil’s Blue Sitting Room

Dr. Gueiros, Churchill, Amb. Muniz, and Chateaubriand at Chartwell, 1949 (Photo: Alamy

August 30, 2022

How South America’s Citizen Kane Acquired His Churchill Painting

Finest Hour 194, Fourth Quarter 2021

Page 31

By Flavio Araujo

Assis Chateaubriand was the Brazilian equivalent to William Randolph Hearst. Brazil’s very own Citizen Kane—a media mogul with an extraordinary talent for self-promotion and generating controversies—founded and directed some of the largest media platforms in his country, including thirty-four newspapers, thirty-six radio stations, eighteen television stations, a news agency, and one weekly magazine. He earned himself the nickname “king maker” by making and breaking the reputations of politicians. Chateaubriand also served as the Brazilian ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1961.

Also like Hearst, Chateaubriand was a renowned art collector. He travelled around the world in search of fine art to purchase after certifying its authenticity. During the late 1940s, he met a gentleman by the name of Georges Wildenstein—a famous French gallery owner, who took an interest in the extroverted Brazilian tycoon about whom the international press talked so much. It was through Wildenstein that Chateaubriand learned about an auction due to take place at Christie’s in June 1949. On offer would be an oil painting by Winston Churchill, which became known as the “Blue Sitting Room.” Clementine Churchill had persuaded her husband to donate the canvas in aid of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA).

The British war leader was Chateaubriand’s hero. He had already dedicated several articles in his newspapers and magazines to Churchill and even invited the former prime minister to visit Brazil. Despite Chateaubriand’s claims that the sole purpose of the invitation was to have Churchill make a few statements to the Brazilian press in favor of free enterprise, the gesture was actually made as an attempt to exploit Churchill’s image and reputation for Chateaubriand’s own political gain. The answer came in the form of a short telegram sent by the Foreign Office to the British embassy in Rio, stating that, unfortunately, the former prime minister would not be able to accept the invitation.

Frustrated after failing to bring Churchill to Brazil and to meet his British hero, Chateaubriand determined that he would buy the painting going under the hammer at Christie’s. On the day of the auction, he checked into a luxury room at Claridge’s Hotel in London and instructed his assistant, Dr. Gueiros, to outbid all the other buyers. Although he had already been warned by Wildenstein that the painting did not have much intrinsic artistic value beyond the mere fact that it was Churchill’s artwork, Chateaubriand won the bidding for the “Blue Sitting Room” with an offer of £1,312— far exceeding the initial bid of £600. Chateaubriand’s secretary had prevailed in a bidding war against American actor Robert Montgomery, who could not afford to outbid him.

2024 International Churchill Conference

One day later Chateaubriand was contacted by Jose Muniz de Aragao, the Brazilian ambassador, informing him that they were both invited by none other than Churchill himself, who was then leader of the opposition, to visit him at Chartwell. Churchill had became curious to meet the avid Brazilian fan of his who had bought the painting. Naturally, Chateaubriand promptly entered his car along with Gueiros and the ambassador, and the three men sped off on their way to visit the British statesman at his country home.

Churchill, wearing his customary siren suit, was expecting the Brazilian party in the garden. After learning how much Chateaubriand spent on his painting, Churchill was quite shocked and reportedly said, “Dear sir, have you lost your mind? None of my paintings are worth that much….”

After some tea and small talk, Chateaubriand set into motion one of his crazy promotional stunts. In his broken English and assisted by the astonished Gueiros, he stated his wish to grant Churchill a title of “the noblest order of chivalry in Brazil—The Order of the Jagunço.” The poor ambassador struggled to define precisely the meaning of the Brazilian term jagunço— which was a cowboy or gunman notorious in the impoverished areas of northeastern Brazil and documented in folklore as both a historic and literary character.

Amused by the situation, Churchill politely submitted himself to the “ritual.” Chateaubriand opened a mysterious suitcase and removed a hat typically worn by jagunços, along with one of their typical (and smelly) coats made from cowhide. He asked Churchill to try them on. Then, as in a ritual ceremony, he tapped each of Churchill’s shoulders with a handmade dagger and, while holding it by its bone-made handle, commenced the ceremony with a speech conducted entirely in Portuguese. Next, in one of his characteristic acts of self-promotion, Chateaubriand insisted that time be made for a photograph of himself and the still-intrigued Churchill. He then bid farewell to his hero and proceeded back to London to celebrate his latest acquisition and brag about his experience with Churchill to the Brazilian press.

Chateaubriand subsequently donated his Churchill painting to the Museum of Arts of São Paulo (MASP), which he had helped to found and where the canvas remains part of the permanent collection. The £1300 Chateaubriand paid for the painting in 1949 would be the equivalent of £47,000 today, which explains Churchill’s astonishment at the sales price. It turned out, however, to be a shrewd investment, since Churchill paintings now regularly sell for millions.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.