Finest Hour 194

Statesmen of the Great War

Sir James Guthrie

September 28, 2022

Winston Churchill and Sir James Guthrie

Finest Hour 194, Fourth Quarter 2021

Page 20

By Alastair Stewart

Alastair Stewart is a freelance writer and public affairs consultant.

Like most things in Edinburgh, the Scottish National Portrait Gallery is quite literally next to my office. Visiting in September was my first opportunity since this magazine published its dedicated Scotland edition last year. At last, I had my picture taken with Sir James Guthrie’s acclaimed portrait of Winston Churchill, which adorned the cover.

Designed by Robert Rowand Anderson and built between 1885 and 1890, the Scottish Portrait Gallery is a gorgeous, Gothic revivalist building. It shares a connection with Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery, where, in one of the main galleries, resides a 16-inch miniature model of the Churchill statue in Woodford Green, London. For good measure, it sits in front of a Spitfire. Glasgow always tries to outdo the capital.

Nevertheless, it is Guthrie’s Churchill portrait that is universally recognisable. But who was James Guthrie, and how did such a renowned picture come from such a neglected area of Churchill study as Scotland?

2024 International Churchill Conference

Churchill and Scotland

For context, Churchill monuments are in short supply in Scotland. Guthrie’s portrait is a global phenomenon, at all of 91.5 x 71.1 cm (and framed at 114.1 x 94 x 7.5 cm).1 The dimensions are essential, for it is considerably more than you will find elsewhere about Churchill’s plethoric Scottish connections (see cover of FH 189).

For me, the portrait captures Churchill’s coy irascibility. He is up to mischief; you can see it in the eyes. He looks almost fed up with his head/hand posture and dreaming of doing something better, something grander.

Guthrie managed to capture the moment Churchill was thinking of something naughty. There is a glow and light in the eyes of a timeless, boundless energy. He is up to something, and it is for onlookers to decide what. As they stand in front of Mr. Churchill in Edinburgh, that answer has delighted Churchill aficionados and passers-by for decades.

South African Adventure

How did such a picture come to be? For starters, it may shock some to learn it is essentially a glorified draft. If there is a worse fight than Edinburgh and Glasgow, it is Edinburgh and London.

The story begins with Colonel Sir Abraham Bailey, 1st Baronet KCMG (6 November 1864–10 August 1940).2 Bailey, by the 1930s, was one of the world’s wealthiest men. The South African diamond tycoon, politician, financier, and cricketer was well known in British society. Bailey was a soldier who served with distinction in both the Boer War and the South West Africa campaign in the First World War. He was also deeply committed to Britain and her empire and active in British politics. His devotion to and advancement of cricket saw regular cricket tours between South Africa and Britain. For Bailey, cricket was an essential mechanism for helping integrate South Africa into the British Empire.3

Bailey advocated and worked for a stronger, more united British empire. He funded the imperialist journal the Round Table from 1910 (an offshoot of the Round Table movement, calling for greater ties between Britain and her colonies).4 During the war, Bailey hosted political meetings at his London house in Bryanston Square.5

With some aptness, Bailey was friends with fellow South African and future Field Marshal Jan Smuts, as well as Winston Churchill, whose own South African connections are well documented. Additionally, Bailey’s son John married Churchill’s daughter Diana at St.Margaret’s Church, Westminster, on 12 December 1932.6

Shortly before the armistice of 11 November 1918, a local art dealer telephoned the director of the National Portrait Gallery (NPG), James Milner. This was done on Bailey’s instruction with a wish to commission two lifesize paintings to commemorate the role of the army and the navy in bringing the First World War to a close.7

Bailey wanted to recognize “the great soldiers who have been the means of saving the Empire” and “the gallant sailors who have taken as great a share in the victory.” His commissions were to show the British Empire “how our policy as far as the colonies are concerned has been successful.”8

Naval Officers of World War I by Sir Arthur Stockdale Cope and General Officers of World War I by John Singer Sargent were commissioned. Bailey paid £5,000 for each painting, in excess of £200,000 in today’s value. Bailey donated the two enormous canvases to the National Portrait Gallery in London, where they can be seen today.9

Milner and the chair of the NPG trustees, Lord Dillon, strongly encouraged that a third painting be commissioned. This one would be a tribute to those British statesmen and leaders who had conducted the war. Bailey agreed.

The third painting, of politicians, was first offered to Sir William Orpen, who declined since he had already been commissioned as the official British artist of the Versailles Peace Conference. Sargent suggested Sir James Guthrie instead.

The Man Comes Around— James Guthrie

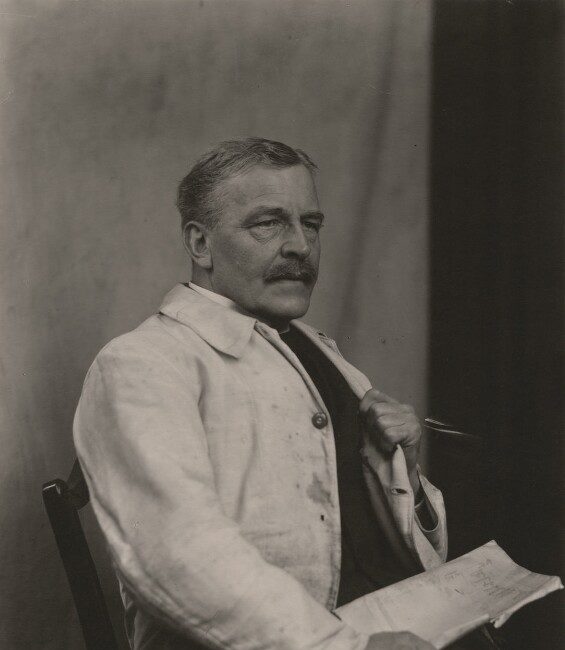

Sir James Guthrie (10 June 1859–6 September 1930) was born in Greenock, Scotland. The youngest son of Reverend John Guthrie, a minister of the Evangelical Union church, and Anne Orr, he initially enrolled at Glasgow University to study law. Fortunately for art, Guthrie abandoned law in favour of painting in 1877. He was mainly self-taught.

Guthrie became one of the leading painters in the group of artists and designers known as the “Glasgow Boys.” They were radical artists, intent on injecting modernism into Scottish art. The group wanted to challenge the tired, saccharine images that dominated the market at the time.10

Guthrie committed himself to paint directly from nature in Scotland. He studied in London and visited Paris. He also experimented with pastel drawings. In 1885 Guthrie established a reputation as a successful portrait painter and launched an award-winning career as a society portraitist.

Guthrie abandoned the radical posture of the Glasgow Boys and moved to Edinburgh. He became president of the Royal Scottish Academy in 1902 and was knighted the following year. He remained president of the academy until 1919.

He lived most of his life in the Scottish Borders, most notably in Cockburnspath, Berwickshire, where he painted some of his most important works. He died at his home in Rhu, Dumbartonshire, in 1930.

Statesmen

In February 1919, Sargent recommended that the trustees approach Guthrie, a close friend. Guthrie frequently used Sargent’s Tite Street studio in London for sittings (it is still active today and used by a working artist).

Guthrie was noted for attempting to capture the character of his sitters rather than displaying a superficial technical virtuosity. It was a skill that would define his seminal work, Statesmen of the Great War.11

The picture stands at some odds with his earlier work. Recently, Glasgow Kelvingrove posted on social media for “Silver Sunday,” the national day for older people. They shared the portrait of “Old Willie” from Kirkcudbright in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. He patiently stopped his chores to pose for Glasgow Boy artist James Guthrie when he visited the village in 1886.12 At the time, Guthrie was not interested in flattery. He wanted to capture the character and experience in subtle facial features. This portrait is a frank and realistic portrayal; there is an apparent dignity in this straightforward depiction. This is not a hero or a person of great renown.

In accepting the request Guthrie, at age 60, knew such a stunning portrait of First World War politicians would be his last major commission. He was correct. He also must have realised a certain grandeur was expected. The group portrait of seventeen figures, some seated and some standing, measures a massive 156 × 132 inches (400 × 340 cm) in portrait form. The oil canvas took six years to complete.

Guthrie began by making sketches of individual subjects. Each required between three and six sittings. The dominion and overseas subjects were in London in the spring and early summer of 1919, with others following during the next two years— including Churchill in 1920.

Churchill, Guthrie, and Scotland

There is a special significance to Guthrie’s Churchill portrait. It was, as has been slightly forgotten, a test subject. As preparatory work, Guthrie painted a study of each subject separately, considerably delaying the completion of his commission.

Guthrie worked on the final composition between 1924 and 1930. As he worked, he pinned individual portraits to the canvas and employed photo collages. This method may explain some of the failings of scale, notably the heads of Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon and former foreign secretary, and Churchill.

Guthrie’s individual portrait of Churchill has an almost innocent, child-like cherubic quality to it. Yet in the final version of the ensemble commission, there is an artificial shaft of light highlighting the centre of the canvas. Churchill is quite literally in the spotlight. As the First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill had been the sheet anchor of imperial strategy in August 1914. Following the Dardanelles fiasco, Churchill’s controversial departure from office in 1915 left serious questions about his judgment. That did not dissipate in the inter-war years. Any prophetic implications this might have for post-1945 viewers are coincidental, but looking at the painting today, one cannot help but ascribe a particular prophetic vision to Churchill’s position.

Guthrie’s seventeen oil studies of the sitters and an oil sketch of the composition were purchased and donated to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery by W. G. Gardiner and Sir Frederick C. Gardiner, Guthrie’s cousins. Today, Churchill’s portrait study forms part of the “Heroes and Heroines” display in Edinburgh. It is inspired by the Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle, whose portrait adorns the wall as you enter. Carlyle’s book On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History presented his theory of the importance of individuals in shaping history.13

The study of Churchill happens to be the most finished among the series representing contemporary politicians. While a draft for the larger, the picture has stood the test of time as a signature image of Churchill as a young statesman.

Churchill sits among the likes of William Gladstone, Ramsay Macdonald, the Duke of Wellington, Queen Victoria, J. M. Barrie, Douglas Haig, and even Harry Lauder (whom Churchill deemed an exemplar of Scottishness worldwide). The gallery also includes an early draft of the final oil canvas, titled Some Statesmen of the Great War (although this is in landscape format and very much lacks the grandeur of the finished work).14

After a delay caused by Guthrie’s illness, Statesmen of the Great War was first exhibited at the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh in the spring of 1930. Guthrie died on 6 September before he could complete the finishing touches. The immense canvas went on display in London in October 1930 and was also donated to the National Portrait Gallery in London, where it resides today. After the Second World War, and long after Guthrie’s death, the painting was renamed Statesmen of World War I.

Imperial March?

Guthrie’s final composition of assembled individuals is an imaginary meeting of the war cabinet. Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour holds forth on some point of diplomatic importance, as David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1916–22), considers matters.

Noticeable other members include Sir Joseph Cook, former Prime Minister of Australia (1913–1914); Billy Hughes, Prime Minister of Australia (1915– 1923); Sir Robert Borden, Prime Minister of Canada (1911–1920); H. H. Asquith, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1908–1916); Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, Secretary of State for War (1918–1919); Ganga Singh, Maharaja of Bikaner; and Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, Secretary of State for War (1914–1916).

A sense of collective responsibility hangs heavy over these men. Many of those seated are contemplating the import of the speech. It is undoubtedly a high-stakes round. Only Churchill seems to have confidence. Ultimately Guthrie rejected the landscape format used by Sargent and Cope, introducing a far grander sense of meaning into his portrait. This is a portrait of the government in action and on the cusp of some momentous decision.

In the background is the Winged Victory of Samothrace, also called the Nike of Samothrace. The significance cannot be ignored: the peace negotiations leading to the Versailles settlement took place in Paris, where this monument stands at the Louvre.

Where the problem rests, and why the individual portrait of Churchill is better appreciated on its own, is in evolving attitudes to war. Guthrie quite clearly had no trouble with Bailey’s underlying imperial agenda. The young radical and iconoclast was by now a rather conservative defender of the empire.

Yet Guthrie’s younger self might have had some qualms at presenting an image of men in their prime, with an untaxed countenance, given the wholesale slaughter of that particular war. The idea of heroic civilian leadership is little more than an indulgence. It ignores the reality that so many of these “decisions,” from the declaration of war to the introduction of conscription and the imposition of political control over the strategy, had been confused, expedient, and self-serving, seriously damaging the nation and the empire.

It is interesting to note that public reaction to the paintings was lukewarm. It corresponded with the societal sentiment that the end of the Great War was the end of bloodletting. It was not an exercise in patriotic affirmation. Classical allegory and the impunity of politicians was no longer in artistic fashion. No one was celebrating victory when the paintings were revealed at the National Portrait Gallery on 27 October 1930.

That the war to end all wars was to be a prelude to something bigger and nastier is a tragic twist of fate. Melancholy sentiment was a staple of the public consciousness after 1918: no one wanted to immortalise what was seen as flawed, if not catastrophically flawed, leadership in the Great War. That Churchill, the most derided, the most chastised leader, became the man most needed in the conflict to come is the great irony.

Aptly, there exist copies of Churchill’s World Crisis series with a dedication to “Abe / from / Winston / with every good wish / 6th Mar 1929.” Bailey was pleased with his commission, describing Guthrie’s picture as “magnificent” and “wonderful,” and even held a celebratory banquet in 1931 for those portrayed in the three pictures.

For Guthrie, the group portrait was the culmination of his career. But Statesmen of World War I is stained with the feeling that the men in it saw themselves in the Olympian way depicted, and this implies a cavalier approach to soldiers on a battlefield.

Churchill, an exceptional painter in his own right, wrote in Painting as a Pastime that “In all battles, two things are usually required of the Commander-in-Chief: to make a good plan for his army and, secondly, to keep a strong reserve. Both these are also obligatory upon the painter.”15 In this, Guthrie and Churchill were entirely correct, commanding, and successful.

Endnotes

1. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-107188

2. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02582470802417458

3. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/2124/sirwinston-churchill-1874-1965-statesman

4. Roger Adelson, “Sir James Guthrie and ‘Some Statesmen of the First World War,’” Scotia: Interdisciplinary Journal of Scottish Studies, 20 (1996), pp. 1–13.

5. https: www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/sir-james-guthrie-228

6. https://gutenberg.ca/ebooks/churchillws-paintingasapastime/churchillws-paintingasapastime-00-h-dir/churchillws-paintingasapaStime-00-h.html

7. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/sir-james-guthrie-228

8. https://archive.org/details/studiointernatio54lond/page/18/mode/2up?view=theater&q=Guthrie

9. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02582470802417458

10. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitExtended/mw0301/Statesmen-of-WorldWar-I#ref1

11. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-andartists/features/glasgowboys

12. https://useum.org/artwork/Sir-Winston-Churchill1874-1965-Statesman-JamesGuthrie-1920

13. http://www.shadyoldlady.com/location.php?loc=1911

14. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/8204/Some-statesmen-great-war

15. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/exhibition/heroes-andheroines-idealism-andachievement-victorian-age

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.