Finest Hour 194

Picturing Churchill:

FIG. 1 . Sir Winston Churchill speaking in Westminster Hall, on his 80th birthday; in the background is the oil portrait of Sir Winston by Graham Sutherland (30 November 1954)

September 28, 2022

Reckoning with the Graham Sutherland Portrait

Finest Hour 194, Fourth Quarter 2021

Page 25

By Allison Leigh

Allison Leigh is Assistant Professor of Art History and SLEMCO/LEQSF Regents Endowed Professor in Art & Architecture I at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

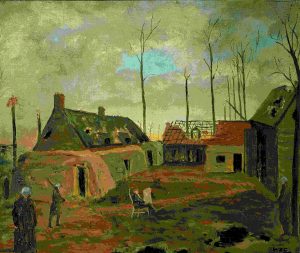

I want to begin by trying to describe a portrait of Sir Winston Churchill that no longer exists.1 It can be seen in a precious still from a recording that was made at its unveiling ceremony in November 1954 (Fig. 1). The painting was a gift to Churchill from both Houses of Parliament, but the statesman was infamously unhappy with the portrait, and we now know that within a year of receiving it at Chartwell, his wife had it destroyed. This story may be familiar. The scandal surrounding the work, which was painted by Graham Sutherland, has been discussed in numerous articles and books, and it was even dramatized on the hit Netflix show The Crown. The eminent English historian Simon Schama showed a precious transparency reproduction of the painting in a BBC documentary series in 2015. That image is nearly all we have left to get a sense of what the original painting looked like (Fig. 2).

In the reproduction, Churchill faces off with the viewer, looking intensely out from what was once the frame. It is hard to imagine how powerful and penetrating that gaze once was. The whole thing looks as though it was painted quite thinly, probably an effect of the statesman’s legs dissolving into nothingness below the calf. This was not an unusual trope for Sutherland; you can see it in other portraits he made in this period.2 But surviving photographs of the artist with the portrait of Churchill still in progress show that it was not the overall body that gave the artist trouble, but the statesman’s face and head (Fig. 3). He painted and repainted this area of the canvas numerous times.

Yet while the facial expression remained unresolved, the body and its position were fixed fairly early on. Sutherland was intent on painting the leader seated and he used a rather square-shaped canvas because it helped support that composition. In an interview he gave soon after the painting was revealed, he described this choice: “I wanted to paint him with a kind of four-square look—Churchill as a rock.”3

2024 International Churchill Conference

We know that the Prime Minister sat for the painter numerous times after Sutherland received the commission in July 1954, and we know that the painting was to be presented to Churchill on the occasion of his eightieth birthday in November. That gave Sutherland just over four and a half months to paint a full-length portrait intended to have a considerable public life. He was, as one might imagine, daunted by the task. He wrote a few weeks after accepting the commission: “it won’t be an easy thing at all, especially in the very short time they are allowing me.” The sittings for the portrait began in late August, after the Prime Minister suggested that Sutherland paint him in his own studio at Chartwell. According to Churchill, it was an ideal location for the sittings because there was a movable platform where his chair could be placed, and he claimed that the painter Oswald Birley had found it very convenient to paint him there in 1946.

What Sutherland produced in that same studio, however, was to be very a different painting. The sittings were, according to later accounts, rife with tension. From the beginning, Churchill asked the painter flat out: “How are you going to paint me? As a cherub, or the Bulldog?” Sutherland made it clear which it was to be in a letter from the time claiming that, from the beginning, Churchill “showed me the Bull Dog.” Tensions only heightened when the artist was forced to inform his sitter carefully that he would not be showing him the day-to-day progress. Churchill immediately protested: “Don’t forget I’m a fellow artist.” This forced Sutherland to relinquish a bit, and he began showing him a limited selection of his sketches. But even this tactic proved ineffective. According to the art historian Jonathan Black, “Churchill would look at a drawing one day and declare: ‘This is going to be by far the best portrait I have ever had done—by far.’ But then the next day he would look at the same drawing and say: ‘Oh no, this won’t do at all. I haven’t got a neckline like that—you must take an inch, nay, an inch and a half off.’”

![FIG. 4 . Graham Sutherland, Winston Churchill, 1954, chalk, 21 1/2 in. x 16 3/8 in. (546 mm x 416 mm), © National Portrait Gallery, London (Given by the artist’s widow, Mrs Graham Sutherland, 1980) [Inventory no. NPG 5333]](https://winstonchurchill.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/FH194-2.png)

Despite these difficulties, the studies which resulted from the sittings are astounding (Fig. 4). Churchill is, in some of the renderings, that impassable bulldog, all furrowed brow and intense absorption. But he is, at the same time, obviously tired, and flashes of sadness, even resignation, are evident behind the irascible veneer. These are sketches of a man who has obviously been worn down by time, but Sutherland seems to have been interested in more than this. For he was also carefully studying the man’s hands, the way he held his cigar, the manner in which he clutched at the arms of the chair, the way his sleeve interacted with his wrist (Fig. 5). Out of all this the overall composition of the painting began to form, yet Churchill’s face continued to be difficult to render (Fig. 6). Whereas the pencil marks comprising the suit in these sketches were usually put down with little fuss and even less correction, Churchill’s head was another matter. That area was often smudged and altered and erased.

![FIG. 5 . Graham Sutherland, Winston Churchill, 1954, pen and ink and pencil, 8 1/4 in. x 6 1/2 in. (210 mm x 165 mm) © National Portrait Gallery, London (Given by the artist's widow, Mrs Graham Sutherland, 1980) [Inventory no. NPG 5334]](https://winstonchurchill.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/FH194-3.png)

This process is echoed in the oil studies Sutherland made in the same weeks. All of them give us some sense of what the original painting must have looked like. One painted sketch, held in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in London, shows the artist’s notes to himself regarding the barrage of colors he saw comprising the old man’s face (Fig. 7). You can still make out his notations: blue high on the forehead, various sections of white along the temple and in the hair, red under the eye, on the cheek, and in the groove next to the ear lobe. Other oil studies show this storm of color as it became more fully realized. In some, Churchill was caught in a moment of perceptive absence, consumed by his own thoughts and hardly aware of the presence of the painter.

![FIG. 6 . Graham Sutherland, Winston Churchill, 1954, pencil and wash, 22 1/2 in. x 17 3/8 in. (570 mm x 440 mm) © National Portrait Gallery, London [Inventory no. NPG 6096]](https://winstonchurchill.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/FH194-4.png)

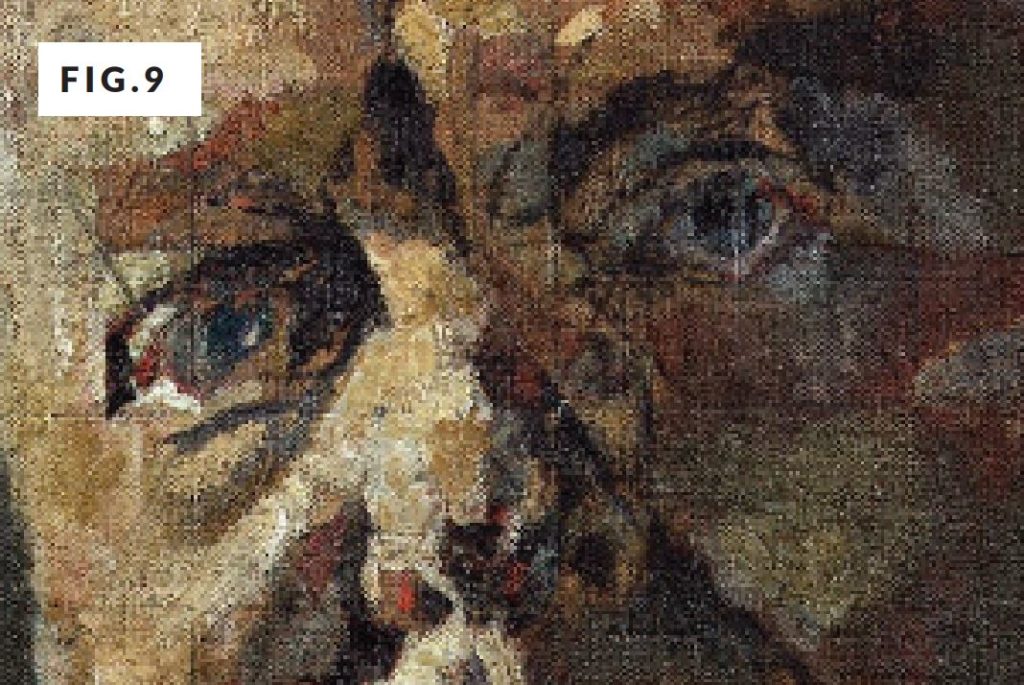

Yet one study in particular strikes me as possessing something of the tragic power of the final portrait that was destroyed (Fig. 8). It is not a large painting, but as you approach it, it is striking how much it holds its own on the wall with all the finished works around it. Even as a sketch, there is an intensity to the gaze of the man portrayed within it that is positively gripping. Looking at it closely reveals how complicated the colors and textures and linework in the final portrait must have been. Sutherland was mapping Churchill’s face in this study, but he was also making a plan of attack. He was trying to break his subject down into manageable pieces, pieces that could be reconstructed into a whole that was more than any simple binary of cherub versus bulldog. He was trying to make Winston a manageable subject for portrayal here—which of course he was not from an intellectual standpoint. He was a giant, a force immeasurable, he was History, he was Britain—but he was also an old man. And it strikes me that this must have been what the portrait captured (Fig. 9). If we imagine that this torrent of color was the face that sat atop that great rock of a man in the final portrait, it becomes clearer why Churchill hated it so much.

![FIG. 7 . Graham Sutherland, Winston Churchill, 1954, oil on canvas, 15 7/8 in. x 12 in. (403 mm x 305 mm) © National Portrait Gallery, London (Given by the artist’s widow, Mrs Graham Sutherland, 1980) [Inventory no. NPG 5331]](https://winstonchurchill.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/FH194-5.png)

At the same time though, I do not think this entirely explains it. And I do not want to fall into the trap of thinking that Churchill’s distaste for the portrait was a simple matter of him not liking how he looked (though I imagine that was indeed part of it). Of the scholars who have investigated the painting, most put forward one of two reasons for its failure. The first follows easily from what I was just saying—that Churchill disliked the work because he saw it as an attempt to diminish his standing in the Commons and to hasten his retirement. The other follows from what Churchill himself said at the ceremony when the painting was first revealed. He famously declared that “the portrait is a striking example of modern art”—a retort that drew much laughter from the audience. This would make it seem that the Prime Minister had something against modern styles of artmaking, that he was against the flattening of the pictorial field or the abstracting of familiar forms. But if one examines what Churchill said in the speech immediately after his infamous jab at modernism, one sees that this does not seem to have been the case. For just after he declared that “the portrait is a striking example of modern art,” he continued, “it certainly combines force and candor. These are qualities which no active member of either House can do without, or should fear to meet.”

![FIG. 8 . Graham Sutherland, Winston Churchill, 1954, oil on canvas, 13 5/8 in. x 12 1/4 in. (345 mm x 311 mm) © National Portrait Gallery, London (Given by the artist’s widow, Mrs Graham Sutherland, 1980) [Inventory no. NPG 5332]](https://winstonchurchill.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/FH194-6.png)

Knowing that Churchill associated modern art (and Sutherland’s painting) with these qualities—force and candor— makes me wonder what it was that he really disliked about this painting. And whether Churchill’s own writings on art might help us determine where the breakdown occurred. Luckily, we have a gem of a text, entitled Painting as a Pastime, which was written by Churchill and first published in 1948. It is packed with insights into what painting was for the statesman, and it lends clues regarding his contempt for Sutherland’s final canvas. When reading it, I have always been struck by one assertion he makes in particular. About halfway through, Churchill declares that “painting a picture is like fighting a battle.”4 He then continues: “In all battles two things are usually required of the Commander-in-Chief: to make a good plan for his army and, secondly, to keep a strong reserve. Both these are also obligatory upon the painter.”

For Churchill, the artist, like a great battle commander, must make a plan by first conducting “reconnaissance”—which for him meant attentively observing “from a special point of view.” Returning to Sutherland’s portrait it seems that this parameter at least was met. The studies, the numerous sittings, his constant reworking of the face—all this was in line with Churchill’s demand that the painter make a plan through careful observation. So, if this was not where Sutherland fell short, perhaps it had to do with a point that Churchill made next, for he believed that the great commanders and the great painters alike needed “reserves.” In the case of painting this meant knowing what proportion of black or white was needed “to produce every effect of light and shade, of sunshine and shadow”—essentially “the relations between the different planes and surfaces with which he is dealing.” Again though, it seems that Sutherland succeeded. The oil studies make it clear how masterful the artist was with what Churchill called proportion and relation. Sutherland hit the paper with white exactly where the light would have reflected off the sitter’s face most intensely— across the bridge of the nose, the tops of the cheeks, the chin, the forehead, and the pate.

To Churchill, the great master of such tonal proportions was J. M. W. Turner (Fig. 10): “When we look at the larger Turners… and observe that they…represent one single second of time, and that every innumerable detail, however small, however distant, however subordinate, is set forth naturally and in its true proportion and relation, without effort, without failure, we must feel in the presence of…the finest achievements of warlike action.” Later, Churchill also praised Turner’s use of color and made it clear that he had strong feelings about this element: “I must say I like bright colours…. I cannot pretend to feel impartial about [them]. I rejoice with the brilliant ones, and am genuinely sorry for the poor browns.” In this regard, Paul Cézanne seems to have been his hero. Churchill describes his ability to infuse even the most commonplace of objects with beauty and also mentions the “wonderfully vivified, brightened, and illuminated” modern landscapes of Manet, Monet, and Matisse.

To be sure, these are not the tastes of a man who does not like modern art. But they may explain why he disliked Sutherland’s portrait. For if Churchill really abhorred browns as much as he claimed, he probably would not have favored the symphony of umbers, bronzes, and chocolates that his own face and body comprised in Sutherland’s canvas. And he might have felt that what he liked so much about the Turners, that they represent a single second of time and that every detail seems natural and without effort—well, he might have felt this was missing from Sutherland’s work. For if the portrait was anything, it was a distillation of many moments of looking, compressed, not into a single second, like Turner’s train slicing through space, but into a man—condensed into someone who was the epitome of time and effort, and looked it.

Churchill knew time and memory were key to painting. And it is, in fact, with a discussion of those elements that he closed his essay, stating that: “The painter must choose between a rapid impression, fresh and warm and living, but probably deserving only of a short life, and the cold, profound, intense effort of memory…from which a masterpiece can alone result.” I think this might be the key. For Churchill, Sutherland’s rushed portrait, his numerous oil sketches, his drab browns, and his failure to distill one single second of time resulted in a work that deserved only a short life because it could not have been more than a rapid impression. What Churchill perhaps failed to see, though, was the intense effort Sutherland made to go beyond his sitter’s hardened bulldog exterior. He waited and he watched, for signs of something else—a softening, an opening, memory, knowledge, power. What Sutherland produced was extraordinary, even if we will never fully know what it originally looked like.

Endnotes

1. The text of this article is adapted from a lecture delivered in January 2020 at a symposium on “Churchill in Conflict and Culture” sponsored by the Hilliard University Art Museum and the National World War II Museum’s Institute for the Study of War and Democracy.

2. See especially his portrait of Edward Sackville-West (also completed in 1954).

3. The following quotes and details surrounding the painting’s commission and execution were derived from Jonathan Black, Winston Churchill in British Art, 1900 to the Present Day: The Titan with Many Faces (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017), pp. 152–77.

4. The following quotes were all taken from Winston S. Churchill, Painting as a Pastime (New York: Cornerstone Library, 1965).

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.