Finest Hour 189

Churchill in Dundee, 1921

Dunrobin Castle

October 4, 2020

Finest Hour 189, Third Quarter 2020

Page 32

By David Stafford

David Stafford is author of Oblivion or Glory: 1921 and the Making of Winston Churchill (Yale University Press, 2019), from which this article is adapted. He formerly served as Project Director of the Centre for the Study of the Two World Wars at the University of Edinburgh.

By 1921 the popularity of Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s Liberal-Conservative coalition was waning, and election talk was in the air. As a senior member of the Cabinet, Winston Churchill’s own political future was seriously at stake. Since 1908 he had been a Liberal MP for Dundee. He once described it as “a seat for life,” but the rise of the Labour Party meant he could no longer take this for granted. The city, Scotland’s third largest, was dominated by the jute industry, and the population was heavily working-class. As a result of the 1918 Representation of the People Act, the electorate had tripled and now also included thousands of women. The city’s slums were notorious for poor housing; drunkenness was rife; and the post-war slump meant unemployment had reached crisis proportions. Children walked hungry and shoeless in the streets.

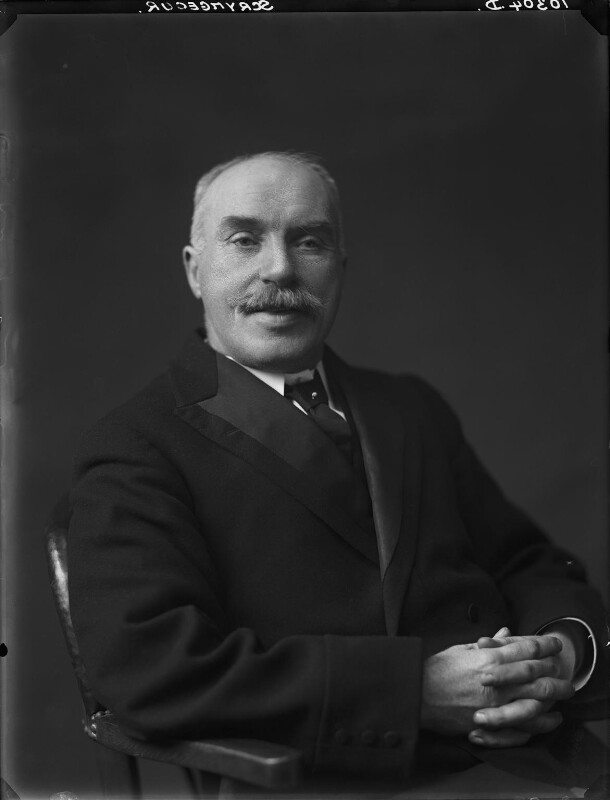

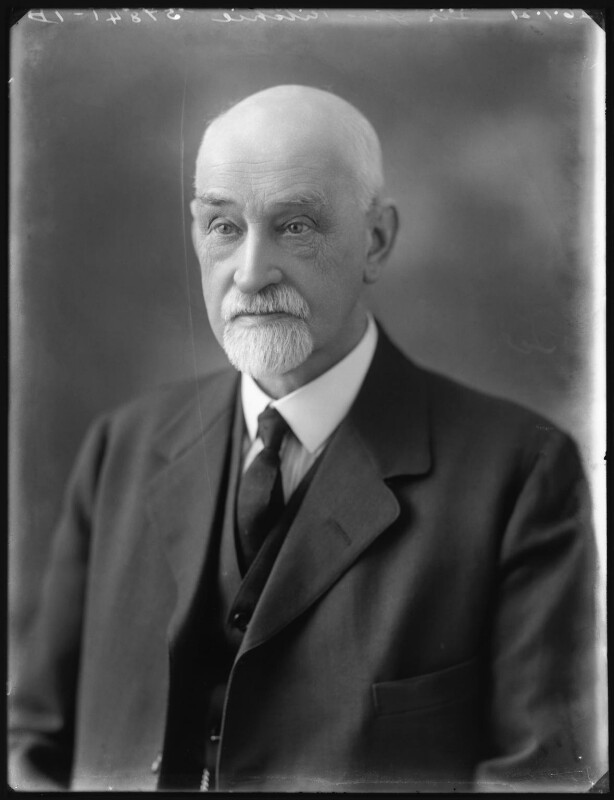

Churchill rarely visited the city more than once a year. It was a long and tedious journey by rail from London. Besides, in local businessman Sir George Ritchie, he benefited from an excellent constituency agent who kept him in touch with the city’s affairs. By now, however, even the normally sanguine Ritchie was seriously worried about the impact of Labour on local Liberal support. Disenchantment with the Government’s austerity programme, he warned Churchill in June, was a serious threat to his seat. The influential Secretary of the Jute Workers’ Union in the city, John Sime, thundered publicly and often that Churchill was “born a Tory, is still a Tory, and always will be a Tory.” Furthermore, Churchill’s violent denunciations of Sinn Fein meant that the city’s Irish voters, once his strong supporters, had also turned against him. A local anti-drink campaigner and socialist, Edwin Scrymgeour, had by now emerged as a serious electoral rival.1

Thus it was that when Churchill arrived in Dundee for his annual visit that September, he ran into serious hostility. Riots by the unemployed had engulfed city streets only days before. Dozens of shop windows were smashed. A crowd of thousands lustily singing the Red Flag besieged the home of the Lord Provost, and the police made dozens of arrests. Anger at both Churchill and the government in London was palpable. Churchill had hardly checked into the Royal Hotel before he was confronted by a delegation headed by Sime angrily demanding the immediate recall of Parliament and the amendment of the unemployment laws. When Churchill met with the City Council the next day, the atmosphere was likewise frosty. As the local MP, he had his constituents’ interest to promote. Being a Cabinet Member, however, meant he also had to defend Government policy. It was an impossible task. The mood was made worse after one of the Council’s Labour members began by furiously accusing the Cabinet of a “brutal and callous” response to the unemployed. Churchill hit back by pointing out how much the government had provided in benefits since the war and blaming a recent wave of strikes for weakening the economy.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Yet the fractious and often emotional council meeting left not just its audience dissatisfied. Churchill himself was deeply discomfited. What he had seen with his own eyes had clearly shocked him. Dozens of shops still had windows boarded up. Many children were visibly in what he described as “a savage and starving condition.” Back at his hotel he sat down and wrote a heartfelt personal letter to Lloyd George confessing that he had become convinced that there was “very great ground for complaint” about the Government’s unemployment policy.2

The Caird Hall Speech

As Colonial Secretary and one of the few Liberal ministers in the Conservative-dominated coalition, Churchill could do little to appease Dundee’s anger about economic and social issues. As a national rather than local actor, however, he was able to turn his 1921 visit to Dundee into a personal triumph.

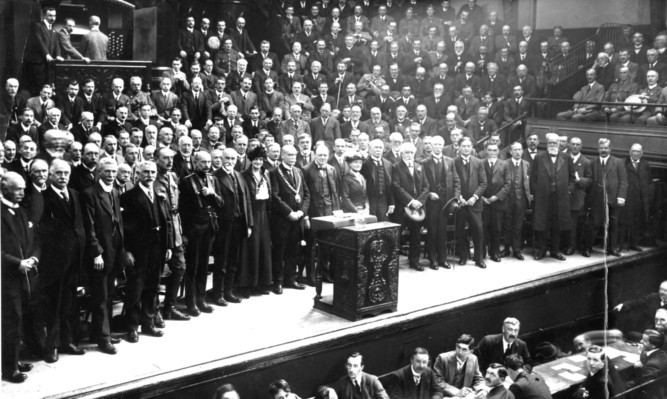

On the following day, Saturday, 24 September, Churchill delivered a speech he had been carefully preparing over the summer at Dunrobin Castle in the Highlands. The venue was the recently completed concert hall named after James Key Caird, a local jute baron and philanthropist who had also sponsored Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ill-fated expedition to the Antarctic. With its neo-classical grandeur and acoustically top-rated auditorium, Caird Hall held out the hope of a more prosperous future for the city on the River Tay. To ensure a sympathetic audience, Ritchie had made the event a ticketed affair. But this was a radicalized Dundee. Hundreds of entry tickets were forged, and only at the last minute were their holders barred from entering. Outside, a hostile crowd of several thousand sang socialist songs, and an unsuccessful effort was made to rush the hall. A heavy police presence attended the proceedings.

Still, despite an occasional heckler, inside Churchill found a responsive audience as he delivered yet another of his many masterful speeches. More importantly, the national press gave his talk widespread coverage. It was in fact a grand civic event, and the hall swelled with between three and four thousand people. The Lord Provost presided, and the platform included many local worthies, including Sir George Ritchie himself, as well as representatives of the Liberal and Conservative Parties. As a significant straw in the political wind, the Lord Provost opened the evening by stressing that he was chairman only in an official capacity. Personally, along with many others present, he had strongly supported the Government during the war. But since then, he told his listeners, many things had appened of which he did not approve. Here was a worrying portent for the future of the Coalition, as well as for Churchill himself.3

Having been alerted—and possibly stimulated—by the Lord Provost’s provocation, Churchill opened his speech by accepting that the present post-war period was a time of great social distress and anxiety where everyone was still suffering from “the grievous wounds of the war,” the imprint of which they would all carry to their graves. From this dark opening, he guided his audience step by step towards a brighter future that echoed familiar sentiments he had been expressing throughout the year. “I look forward confidently,” he eventually concluded amidst cheers, “to an ever closer association between the United States and the British Empire, for it is in the unity of the English-speaking peoples that the brightest hopes for the progress of mankind will be found to reside.”

How was this future to be reached? Churchill’s answer was by following the path of reconciliation. This was the time, he declared after moving on from his sombre opening scene, “for composing differences, for assisting each other, for leaving alone all quarrels and co-operating in the rebuilding as quickly as possible of the threatened prosperity of the country. Classes and nations must help each other.” One way was to settle war debts and re-establish a healthy and prosperous system of tariff-free international trade. Another was for the Great Powers of Europe, as well as of the Pacific, to create a climate of peaceful co-operation. Here he looked ahead to the near future and the forthcoming international naval disarmament conference to be held in the American capital. “I have high hopes of this Washington Conference,” he told his listeners. “It marks the re-entry of the United States into the responsibilities and difficulties of world politics,” and, he added, made him confident of the Anglo-American future.

Of course, perils awaited. Not surprisingly, Churchill pronounced that the greatest of these was Bolshevism. Earlier that month the Dundee Advertiser had carried a full-page appeal requesting donations for famine relief in Russia, where millions were starving in the aftermath of the Revolution and Civil War. Children were often abandoned and reduced to eating grass, roots, and rubbish. In total, some thirty-five million Russians were suffering. “One of the world’s greatest granaries,” Churchill declared, “has been reduced through four years of Socialism and Bolshevism to absolute starvation.” Worse, he added, Lenin and Trotsky had killed without mercy all those who opposed them and now lived off the wealth of those they had dispossessed. This claim rang true to his audience. In a despatch from Helsinki, the local paper had recently reported that sixty-one people had been shot in Petrograd for being implicated in the latest “plot” against the regime; most, it seemed, were “men of education, including two professors and a famous sculptor.” Churchill’s attack on the perils of Bolshevism concluded on a familiar note. Domestic supporters had been doing their best to disrupt the economy through strikes and disputes and “to ruin us here in Britain.” Luckily, Churchill added in a typical aside that drew approving laughter, “we always seem to get these foreign diseases in a less acute form.”

Churchill then asserted that the more immediate threat lay in Ireland, where a truce between Sinn Fein and Britain in the Irish war of independence had been declared that July. This was the centrepiece of his talk, and the one his audience was most anxious to hear. Again, reconciliation was the central theme. Past quarrels now had to be put aside, and this included, he stressed, differences between the Conservatives and Liberals themselves on how to deal with Ireland. But if the message was reconciliation, his tone was firm. In its offer of Dominion status to southern Ireland, the Government had gone “to the utmost limit possible.” So far, the negative response of Eamon de Valera, Sinn Fein’s leader, had been disappointing and puzzling. True, he was “riding a nationalist tiger,” and allowance had to be made for that. Nonetheless, Churchill told his audience that he was still uncertain where the Irish leaders stood. “I only know,” he said, “where we stand. We have reached the end of our tether.” This prompted cheers in the audience.

Churchill then added a sobering note by raising the prospect of an independent Irish Republic and what it would mean. He painted a dark and ominous picture of what could lie ahead: a fortified frontier between north and south with hostile armies on each side; constant fear that the Irish Republic was intriguing with other countries against Britain, possibly by giving them submarine bases; a tariff wall between the two nations; and hundreds of thousands of Irishmen living throughout the Empire immediately being declared “aliens” if war broke out between Britain and Ireland. “What a ludicrous and what an idiotic prospect is unfolded before our eyes,” he declared. “What a crime [Sinn Fein] would commit if…they condemn themselves and their children to such misfortunes.” To head off this dark future, a conference was clearly needed. It would be wise to be outspoken, and foolish to encourage false or dangerous hopes. It had to be a successful conference. “Squander it,” he warned in words clearly designed for the ears of de Valera, “and peace is bankrupt.”4 His final words linked Ireland’s fate to his broader vision for Britain:

When in moments of doubt or hours of despondency we fear that the course of events we are pursuing towards the Irish Sinn Feiners is repugnant to some of our feelings…we must cheer ourselves by remembering that a lasting settlement with Ireland—a healing of the old quarrel, a reconciliation between two races—would not only be a blessing in itself inestimable, but with it would be removed the greatest obstacle which has ever existed to Anglo-American unity, and that far across the Atlantic Ocean we should reap a harvest sown in the Emerald Isle.5

Peacemaker

The speech did little to alter minds in Dundee about Churchill’s suitability as their MP. After he finished speaking, Churchill had to exit by the back door and be hastily driven to his hotel. More than a year later, the governing coalition collapsed, and Churchill was defeated in the general election that followed. Neither Lloyd George nor the Liberals would ever again head a government in Britain. For the first time, Labour formed the official opposition. Before that, however, Churchill’s Caird Hall speech had guaranteed his selection as one of the chief British negotiators in talks with Sinn Fein that culminated in the creation of the Irish Free State. This, along with his settlement of Britain’s residual obligations in the Middle East during his time at the Colonial Office, meant that Churchill, contrary to his image as a belligerent warmonger, could now legitimately claim to be a peacemaker.

Churchill’s final two years as MP for Dundee marked an important step in his political rehabilitation. It had been sixteen years since his first biographer, Alexander MacCallum Scott, had identified him as a potential prime minister. The Dardanelles campaign in 1915 had put a brutal end to that perception. Yet by the autumn of 1921, the words “statesman” and “leader” were again being attached to Churchill’s name. In an editorial entitled “An Essay in Statesmanship,” The Times declared that “Discarding the debased coinage of party politics,” Churchill in his Dundee address “used the nobler currency that once used to pass and will, we trust, pass again between British public men and the British public.”6

Even more outspoken was an article in the weekly magazine Outlook. “Were I an ambitious young backbencher,” declared its anonymous author, “I would hitch my wagon to the star of the Colonial Secretary, a star that once seemed to be waning to telescopic dimensions, but of late has rapidly waxed from the third to the second magnitude and, in my opinion, will go on waxing. Winston seems to be the only one in the Cabinet with a sane and comprehensive view of world politics.” This was all the more remarkable a declaration because the magazine traditionally supported the Conservatives, who had long loathed Churchill as a traitor to their cause. It was an intriguing straw in the wind hinting at a major shift in the political landscape. Indeed, only three years later, Churchill would return to the Conservative fold—although no longer as a Scottish MP”—proudly don his father’s robes as Chancellor of the Exchequer, and confidently imagine that his next major move would be into 10 Downing Street.7

Endnotes

1. Sir George Ritchie to Churchill, 17 June 1921, in CHAR 5/24, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge; for a broad overview of Churchill and Dundee, see Tony Paterson, Churchill: A Seat for Life (Dundee: David Winter and Son, 1980).

2. Churchill to Lloyd George, 23 September 1921, in CHAR 5/24.

3. Dundee Advertiser, 26 September 1921.

4. For the text of the Caird Hall speech, see Robert Rhodes James, ed., Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches, Vol. III, 1914–1922 (New York: Chelsea House, 1974), pp. 3128–31.

5. Ibid., p. 3140.

6. The Times, 26 September 1921.

7. Outlook, 22 October 1921.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.