Finest Hour 189

“He Is a Great Man”

Lord Rosebery in Harper's Weekly circa 1902

October 4, 2020

Finest Hour 189, Third Quarter 2020

Page 20

By Piers Brendon

Piers Brendon is author of Churchill’s Bestiary: His Life Through Animals (2018) and former Keeper of the Churchill Archives Centre.

On a visit to Lord Rosebery’s palatial country house Mentmore in 1880, the radical politician Sir Charles Dilke noted that his host was “the most ambitious man I had ever met.” Years later Dilke added a marginal comment, “I have since known Winston Churchill.”1 Needless to say, young Winston was ambitious, occasionally telling—and convincing—complete strangers that he was destined to lead his country. But Rosebery’s ambitions were more diffuse. They were famously summed up in his expressed desire to marry an heiress, win the Derby and become Prime Minister. Perhaps this story is apocryphal since the three wishes were apparently made at the Mendacious Club, which he formed with the American socialite and political fixer Sam Ward. Yet all three were fulfilled, which did not prevent Rosebery’s life from becoming what the journalist A. G. Gardiner called a “tragedy of unfulfilment.”2 That life fascinated Churchill. As he wrote in a sparkling essay on Rosebery in Great Contemporaries, “With some at least of those feelings of awe and attraction which led Boswell to Dr. Johnson, I sought occasions to develop the acquaintance of childhood into a grown-up friendship.”3

Lord Randolph

Archibald Primrose (1847– 1929), who became fifth Earl of Rosebery at the age of twenty, had been two years ahead of Winston’s father, Lord Randolph Churchill, at Eton. They forged a close bond at Oxford where they were both members of the fast, aristocratic set whose main activities were drinking, gambling and sport. Unlike Lord Randolph, younger son of the Duke of Marlborough, Rosebery was immensely rich, inheriting over 20,000 Scottish acres and a clutch of stately homes to go with them. So while Lord Randolph merely kept his own pack of harriers at Merton College, Rosebery spent a small fortune on the Turf. The Dean of Christ Church was not amused, insisting that Rosebery must either give up his race-horses or his undergraduate studies. Characteristically Rosebery chose to sacrifice the latter, departing from the university without a degree. This was the sort of grand gesture that appealed to Lord Randolph, who shared Rosebery’s intense pride of caste whereby, as an Eton contemporary wrote, “a man seems to ascend in a balloon out of earshot every time he is addressed by one not socially his equal.”4

Rosebery and Lord Randolph, however, had much more in common than patrician hauteur. They were both clever, erratic, sardonic, prickly, self-indulgent, and highly strung. Both were mesmeric orators, captivating huge audiences on the stump and holding sway in parliament, though Rosebery lacked Lord Randolph’s common touch and his brutal capacity for invective. Instead, wrote one biographer, Rosebery adopted in the House of Lords “the tone of a very consciously sane chaplain addressing the inmates of a home for imbeciles.”5 As political antagonists they occasionally attacked each other: in 1885 Rosebery declared that since it took forty generations to turn a wild duck into a tame duck “you cannot expect Lord Randolph Churchill to become a serious statesman all at once.”6

2024 International Churchill Conference

Yet they had some ideas in common: both aspired to be national leaders even at the cost of party loyalty, and, just as the Tory Lord Randolph added Upper Burma to the British Empire, so the Liberal Rosebery added Uganda. They enjoyed a bantering personal relationship. When Rosebery complained that Lord Randolph’s reference to his “enormous and unlimited wealth” would inundate him with mendicants, his friend retorted: “Your letter is most affecting but what can I do? You support that old monster [Gladstone], and therefore you must be fleeced and fined in this world.” When Lord Randolph asserted, “If there’s one thing I hate and detest it is political intrigue,” Rosebery responded with “a solemn and deliberate wink.”7

Privately Rosebery reckoned that to gain political advantage Lord Randolph would “sell his own soul.”8 But they remained close, though Lord Esher, another Etonian, considered Rosebery incapable of true friendship and “rather of the oyster tribe.”9 In 1906 Rosebery wrote a brief life of Lord Randolph, which was notable alike for its affection, brilliance and candour (tempered by discretion). It had the merit, too, of revealing much about its author, who paid vivid tribute to the wayward charm of his subject. With his weird jay-like laughter, his poached-egg eyes and his jaunty moustache, which had an emotion of its own, Lord Randolph was a “striking combination of the picturesque and the burlesque.”

His demeanour, his unexpectedness, his fits of caressing humility, his impulsiveness, his tinge of violent eccentricity, his apparent dare-devilry, made him a fascinating companion; while his wit, his sarcasm, his piercing personalities, his elaborate irony, and his effective delivery, gave astonishing popularity to his speeches.10 Rosebery himself was also freakish and flippant, so much so that he was urged to take a more serious tone by Queen Victoria, one of two people on earth who really frightened him, the other being Bismarck.

Lord Randolph was handicapped, however, by a disease (probably syphilis, though this diagnosis has been challenged), which Rosebery thought was partly responsible for Lord Randolph’s fatal resignation as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1886. In the ensuing years, as Rosebery unforgettably wrote, Lord Randolph “died by inches in public…the chief mourner at his own protracted funeral.”11 His career ended at the very time Rosebery was establishing himself as Gladstone’s political heir. Yet Rosebery was handicapped by psychological ills. The spoilt child became an adult prima donna, a creature of moods and whims and crotchets. He was hyper-sensitive and ultra-fastidious. He craved power but refused frequent offers of preferment, disdaining the Westminster hurly-burly and desiring (in the oft-quoted words of his Eton tutor) “the palm without the dust.”12 And when in 1894 he was summoned to fill the vac- uum left by Gladstone, Rosebery likened the Prime Ministership to a dunghill. With a divided cabinet, confused policies and minimal achievements, he resigned just over a year later, extricating himself from what he later called an “evil-smelling bog.”13

Young Winston

In 1896 Rosebery also resigned as leader of the Liberal party, making a speech, which Winston Churchill extolled in a letter to his mother.

A more statesmanlike & impressive utterance is hard to imagine. He is a great man— and one of these days he will again lead a great party. The only two great men now on the political stage will be drawn irresistibly together. Their political views already coincide and L[or]d Rosebery and Joe Chamberlain would be worthy leaders of Tory Democracy.14

It is remarkable that even as a fresh-faced subaltern, just posted to India, Churchill was conjuring with the idea of realising his father’s dream of popular conservatism. This would combine perfectly, he thought, with Rosebery’s avowed policy of imperialism and social reform, all to be carried out by a new, centrist political coalition. But their adult relationship got off to a rocky start. At a country house party Churchill gave such a voluble and bumptious account of his escape from Boer captivity as to stampede fellow guests from the room. Rosebery complained, “I was almost jammed in the door.”15

Nevertheless Rosebery congratulated Churchill on his “fruitful and honourable career in South Africa”16 and invited him to lunch to meet the Duke of Cambridge. When Churchill sent him proofs of his book London to Ladysmith via Pretoria (1900), Rosebery responded generously: “What a natural wholesome manly record. We heed that particular species as no other European nation does.”17 He was still more effusive in February 1901, shortly after Churchill’s election to parliament:

Let me wish you heartily joy of your maiden speech. It is a great thing to have got it over, for it is a disagreeable though necessary operation, like vaccination circumcision and the like. But it is much more to have achieved a triumph, as you have.18 Soon Churchill was visiting Mentmore and the Durdans, Rosebery’s Epsom mansion, where the younger man had to apologise for frightening his horses while learning to drive a motorcar. Rosebery also showed concern about his diction and Churchill wrote, “I will take your advice about elocution lessons, though I fear I shall never learn to pronounce my S properly.”19 By the autumn Rosebery was assuring Churchill, “It is a great pleasure to me, both for your father’s sake and your own, to see you whenever you like.”20

For the next few years Churchill tried to persuade Rosebery to take the lead in forming a middle “party wh[ich] shall be free at once from the selfishness & callousness of Toryism on the one hand & the blind appetites of the Radical masses on the other.” The risks would be great, Churchill said, and “only the conviction that you are upholding the flag for which my father fought so long & so disastrously would nerve me to take the plunge.”21 Rosebery warned him not to “compromise your career by premature action.”22 He himself was morbidly passive and viscerally unreliable, “not a man to go tiger-shooting with.”23 He cherished his independence and (what Churchill called in a cancelled passage in Great Contemporaries) “his superiority to the common truck.”24

Sometimes Rosebery literally held aloof. In August 1903 he wrote to Churchill from Bad Gastein:

Here I am on a lonely peak, above but not in sight of all the Kingdoms of the world. It is an unspeakable solitude where the farming policies of [the Duke of] Devonshire and J[oseph] C[hamberlain] appear as phantoms from another world.25

This was a facetious reference to Chamberlain’s campaign to abandon free trade for imperial protection, the issue that caused Churchill to quit the Tories for the Liberal party in 1904. Rosebery also opposed tariffs, arguing (in a curious anticipation of the anti-Brexit case) that “a great commercial country like ours cannot reverse a commercial system, on which so much prosperity has been built, on a hypothesis.”26 But far from embracing allies, he insisted on ploughing his own furrow.

By 1905 Churchill was becoming disillusioned with Rosebery, who annoyed him by stating that, as a qualification for office, eloquence was worth less than proven administrative ability. Rejecting Churchill’s “poisonous insinuation” that this referred to him and Lloyd George, Rosebery professed to favour the promotion of “young talent” rather than “the system by which ministerial Struldbrugs…claim office till they drop into unregretted graves.”27 Worse still, Rosebery withheld crucial assistance over Churchill’s biography of his father. He first claimed that he had burned his recollections of Lord Randolph. Later he said that they had turned up but refused to let Winston see them, evidently intent on publishing his own memoir.

Oddly enough, Churchill told a different story in Great Contemporaries, asserting that he did not want to incorporate Rosebery’s work into his own, particularly as he had described Lord Randolph at school as a “scug.”28 Rosebery tried to mollify Churchill with lavish praise for his “marvellous picture of a gifted, complicated ill-fated lovable being, written with the affection of a son” (though privately he thought it was too filial).29 And he unconvincingly referred to his own memoir as an advertisement for Churchill’s biography. But the episode rankled, and years later Rosebery’s son was startled by a Churchillian growl: “Your father called my father a scug.”30

Churchill was further alienated when, on the eve of what proved to be a crushing Liberal victory at the polls, Rosebery disowned the party’s policy of gradual advance towards Irish Home Rule. To his mother Churchill wrote, “Rosebery has I regret to say greatly injured himself by his reckless speech. Parties do not forgive this kind of unnecessary quarrelsomeness at critical moments.”31 They remained on intimate terms. On becoming Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies in the new government, Churchill told Rosebery, “They bought me cheap.”32 Rosebery treated him to health bulletins. He was plagued by insomnia: “After a good night I am a man, after a bad night I am a mouse.”33 A month later, in March 1907, Rosebery wrote: “influenza and malaria make a diabolical combination. My only comfort is that I am not in office. In that I thank God hourly if not momentarily.”34 Edward VII himself deplored Rosebery’s barren self-isolation. In an involuntary tribute to the Earl’s enigmatic character, the King urged him “to rise like a sphinx from your ashes.”35

In similar vein Sir Edward Grey, Liberal Foreign Secretary, had once said that Rosebery’s genius elevated him above the crowd: “It’s as if God dangled him amongst us by an invisible thread.” But sitting “godlike, above the melée,” as Grey’s biographer put it, Rosebery became an increasing irrelevance.36 He was certainly far-sighted. He visualised the Empire as a Commonwealth of Nations, predicted that the entente cordiale with France would lead to war with Germany and divined that Liberalism would be squeezed between Conservativism and Socialism. But he was a Whig oligarch among progressive democrats, the last British Prime Minister never to have sat in the Commons. Churchill exclaimed to Gardiner:

What a mind, what endowments that man has! I feel that if I had his brain I would move mountains. Oh, that he had been in the House of Commons! There is the tragedy. Never to have come into contact with realities, never to have felt the pulse of things—that is what is wrong with Rosebery.37

This was the burden of Churchill’s essay in Great Contemporaries. Rosebery carried into “current events an air of ancient majesty.”38

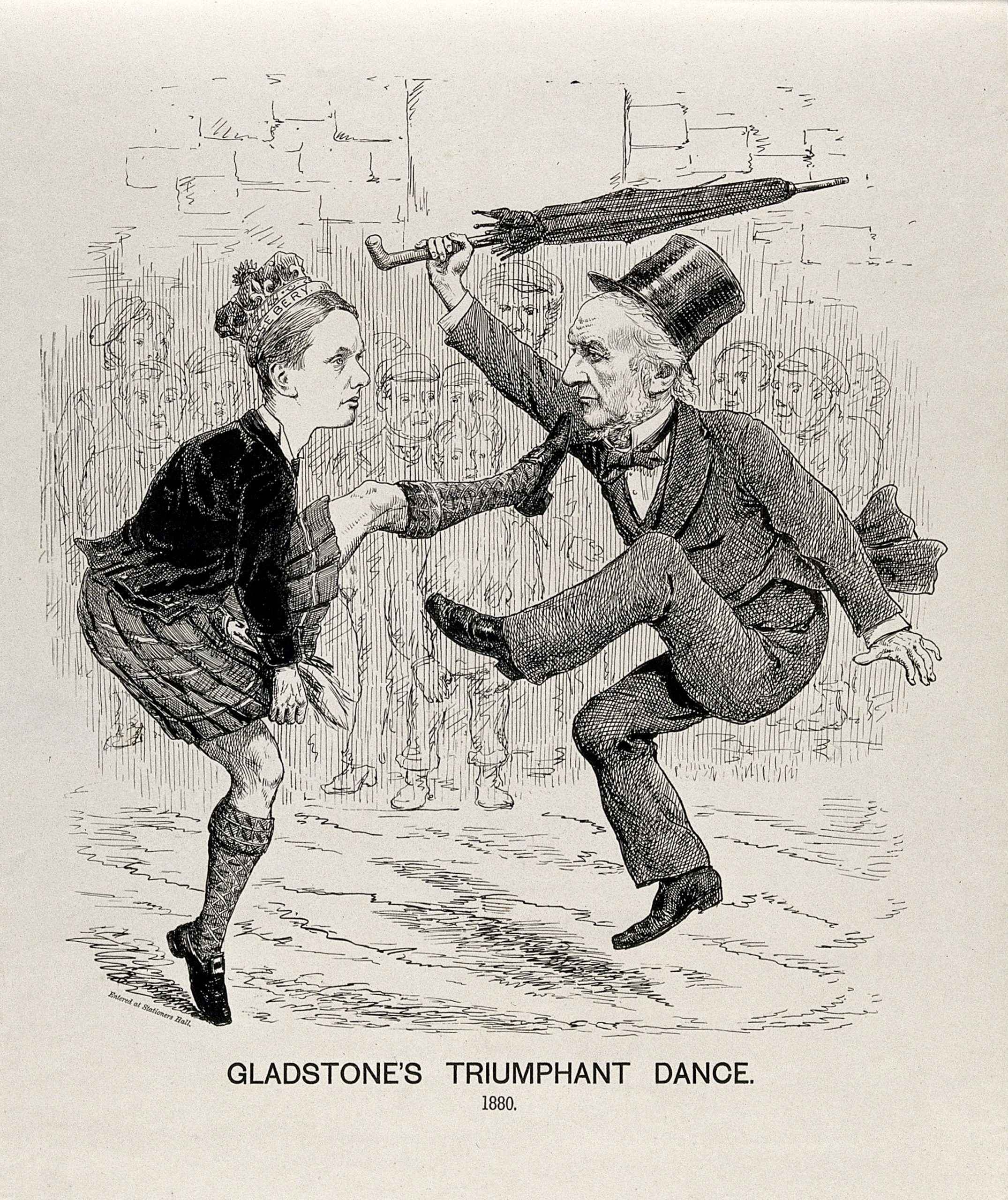

Lord Rosebery, wearing a kilt and a crown

Still Friends

In person Rosebery remained supremely gracious. When Churchill’s engagement to Clementine Hozier was announced, he wrote to Winston:

I have seen and admired your bride, and honestly believe that you have the fairest prospects of happiness. I am sure too that such a marriage will be an incalculable solace and assistance in your public career, so brilliant and successful and affluent of future distinction…just as an ill-match is hell, so a fortunate one is the Kingdom of Heaven on earth.39

As Churchill pursued radical social policies, the political gulf between the two men widened. Despite his theoretical dedication to noblesse oblige, a dedication Churchill shared, Rosebery opposed the introduction of old age pensions. He also attacked Lloyd George’s People’s Budget, denouncing it as “Socialistic” and defending dukes as “a poor but honest class.”40 Churchill was scathing about his performance, describing it as ignorant, inaccurate, inconclusive, tedious and feeble beyond words: “He really reminds me of a rich selfish old woman grumbling about her nephew’s extravagance.”41

In 1911, the Parliament Act restricted the power of the House of Lords. After speaking against it and voting for it, Rosebery never again entered that chamber. He became, as the Archbishop of Canterbury wrote, “a complete outsider in national affairs.”42 Churchill saw him occasionally and still delighted in his scintillating talk, which was likened to a fountain playing in the sunlight. He had learnt much from Rosebery, not least from his political failure, his crippling dilettantism, his lack of bulldog spirit. And Rosebery did Churchill one last service, urging him to write about “Duke John,”43 as he dubbed the victor of Blenheim, and lending him John Paget’s Examen, a rebuttal of Macaulay’s indictment of Marlborough. Churchill told Rosebery that this book had cleared away some of the difficulties he felt about writing a biography of “‘Duke John.’ (That would be rather a good title wouldn’t it?)”44

In his final years Rosebery’s health deteriorated and he described himself as a “well-preserved corpse.”45 When Prime Minister he had cheered himself up by humming “Rule Britannia.” As Churchill did not fail to mention in Great Contemporaries, Rosebery died to the strains, played on the gramophone at his instruction, of the Eton Boating Song.

Endnotes

1. Randolph S. Churchill (first two vols.) and Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill [henceforth Churchill] (London: Heinemann, 8 vols., 1966–88), vol. I, p. 53.

2. A. G. Gardiner, Prophets, Priests, and Kings (London: Alston Rivers, 1908), p. 278.

3. Winston S. Churchill, Great Contemporaries, edited by J. W. Muller (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2012, first published in London by Thornton Butterworth, 1937), p. 7.

4. Robert Rhodes James, Rosebery (London: Phoenix, 1995), p. 25.

5. E. T. Raymond, The Man of Promise: Lord Rosebery (London: Unwin, 1921), p. 34.

6. T. F. G. Coates, ed., Lord Rosebery: His Life and Speeches, Vol. I (London: Hutchinson, 1900), p. 463.

7. Marquess of Crewe, Rosebery, Vol. II (London: John Murray, 1931), pp. 491 and 493.

8. R. F. Foster, Lord Randolph Churchill (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981), pp. 339–40.

9. James Lees-Milne, The Enigmatic Edwardian (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1988), p. 97.

10. Lord Rosebery, Lord Randolph Churchill (London: Arthur L. Humphreys, 1906), pp. 34–35 and 120.

11. Ibid., pp. 79 and 199.

12. Churchill, Great Contemporaries, p. 11.

13. Crewe, Rosebery II, 659. Rosebery’s most recent biographer plausibly discounts the theory (advanced in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and elsewhere) that he suffered a nervous and physical breakdown resulting from terror about being implicated in a homosexual scandal at the time of the trial of Oscar Wilde. It is true that Rosebery had been adored by a pederastic schoolmaster at Eton and was reputed in homosexual circles to be what his (and Wilde’s) accuser, the Marquess of Queensberry, called a “Snob Queer.” He also collected pornography, indulged in smoking-room ribaldry and took care to open his own letters. But Rosebery had been happily married (to Hannah Rothschild), and his health problems seem to have been largely caused by “the unique pressures of his post as Prime Minister.” (Leo McKinstry, Rosebery: Statesman in Turmoil [London: John Murray, 2006], pp. 363 and 366.)

14. Churchill I, p. 313.

15. Rhodes James, Rosebery, p. 418.

16. CHAR 1/25/19, Rosebery to Churchill, 21 July 1900, Churchill Archives Centre (CAC), Cambridge.

17. CAC, CHAR 1/25/26, Rosebery to Churchill, 3 September 1900.

18. CAC, CHAR 1/29/7, Rosebery to Churchill, 20 February 1901.

19. McKinstry, Rosebery, p. 455.

20. CAC, CHAR 1/29/36, Rosebery to Churchill, 23 September 1901.

21. Churchill II, p. 47.

22. CAC, CHAR 2/2/20, Rosebery to Churchill, 12 October 1902.

23. Rhodes James, Rosebery, p. 258. This was Tim Healy’s verdict.

24. CAC, CHAR 8/579/40.

25. CAC, CHAR 2/8/51, Rosebery to Churchill, 10 August 1903.

26. McKinstry, Rosebery, p. 460.

27. CAC, CHAR 2/22/84, Rosebery to Churchill, 4 May 1905. Rosebery’s amusing but specious rhetoric led him astray: although Swift’s Struldbrugs grew old, they did not die.

28. Churchill, Great Contemporaries, pp. 8–9. “Scug” was Etonian slang for boor.

29. Churchill II, p. 141.

30. Rhodes James, Rosebery, 215.

31. CAC, CHAR 28/27/48, Churchill to Lady Randolph Churchill, 28 November 1905.

32. Rhodes James, Rosebery, p. 462.

33. CAC, CHAR 1/65/11–12, Rosebery to Churchill, 13 February 1907.

34. CAC, CHAR 1/65/23–24, Rosebery to Churchill, 5 March 1907.

35. Rhodes James, Rosebery, p. 463.

36. G. M. Trevelyan, Grey of Falloden (London: Longmans Green, 1937), pp. 80 and 76.

37. Gardiner, Prophets, Priests, and Kings, p. 280.

38. Churchill, Great Contemporaries, p. 9.

39. CAC, CHAR 1/73/70, Rosebery to Churchill, 15 August 1908.

40. Rhodes James, Rosebery, p. 465.

41. Churchill II, 327.

42. G. K. A. Bell, Randall Davidson, vol. II (Oxford University Press, 1935), p. 869.

43. Winston S. Churchill, Marlborough: His Life and Times (London: George G. Harrap, 1947), p. 18.

44. CAC, CHAR 8/196, Churchill to Rosebery 24 December 1924.

45. McKinstry, Rosebery, p. 490.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.