Finest Hour 189

A Scottish Honorary Degree

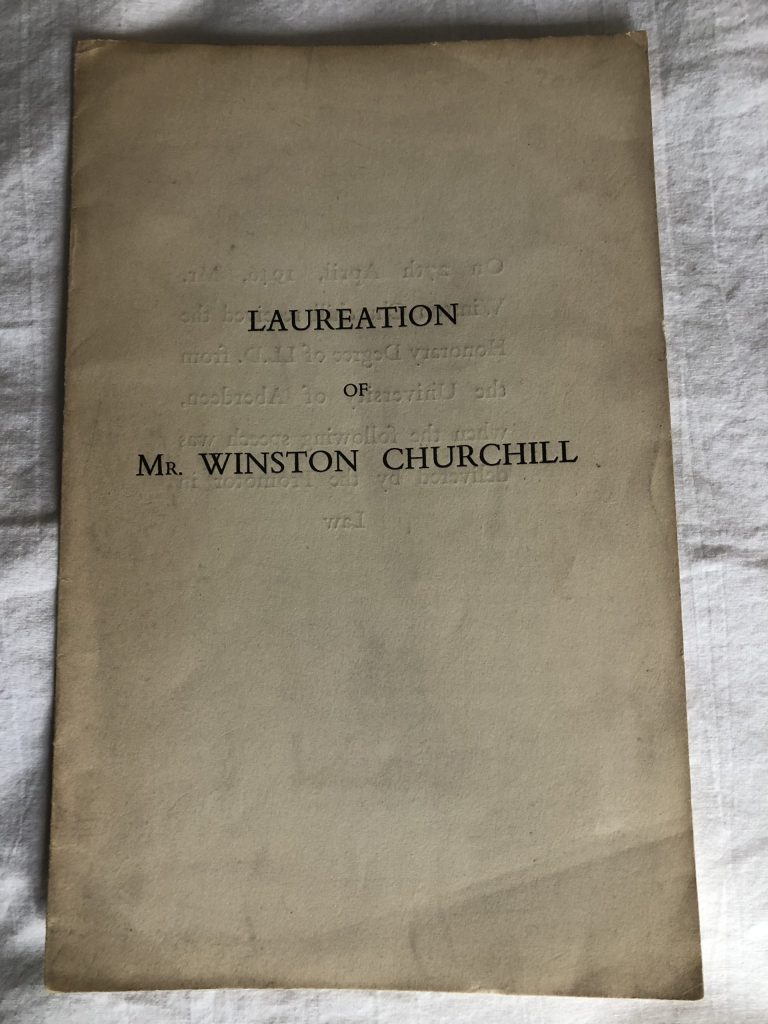

Program for honorary degree ceremony at the University of Aberdeen.

October 4, 2020

Finest Hour 189, Third Quarter 2020

Page 38

By Ronald I. Cohen

Ronald I. Cohen MBE is author of A Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill (2006).

Readers will be surprised to learn how few honorary degrees were conferred on Winston Churchill in the course of his long life. Although the practice of granting a degree honoris causa is more than five centuries old, the practice was not common until this past century. Even then, when such recognitions began to proliferate, Churchill was granted only fourteen in all. Only one of these came before he was prime minister (he was at the time Chancellor of the Exchequer). Three more came during the Second World War, all from North America, and ten more followed after the hostilities. The first of the post-war degrees that he received from universities in the United Kingdom was presented by the University of Aberdeen.

In some respects, the recognition from Scotland was not surprising. Churchill had already received the Freedom of the City and Royal Burgh of Edinburgh in October 1942, the first of forty-two City Freedoms that he ultimately garnered worldwide. On that occasion, Churchill said to the audience in Usher Hall:

I have myself some ties with Scotland which are to me of great significance—ties precious and lasting. First of all, I decided to be born on St. Andrew’s Day—and it was to Scotland I went to find mywife, who is deeply grieved not to be here today through temporary indisposition. I commanded a Scottish battalion of the famous 21st Regiment for five months in the line in France in the last war. I sat for 15 years as the representative of “Bonnie Dundee,” and I might be sitting for it still if the matter had rested entirely with me.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Dundee Denial

It did not rest with him. In the general election of 1922, Churchill lost a bitter battle for the seat at Dundee that he had held since 1908, standing fourth of six candidates. “Winston thought his world had come to an end. Not since the days of his lonely childhood, or even at the time he had lost the Admiralty, had he felt such a depression of spirit.” He never visited the city again. Years later, in October 1943, the Dundee City Council attempted a rapprochement and voted to “do ourselves and the community great honour by making him a Burgess of the city.” In response, Churchill’s Private Secretary, T. H. Beck, rebuffed the offer in the following terms:

I am desired by the Prime Minister to acknowledge your letter of October 8th, inviting him to accept the freedom of the City of Dundee, and to thank you for your courtesy. Mr Churchill regrets he is unable to accept the honour which you have proposed to confer upon him.

Churchill ultimately became a Freeman of all of the other cities he had ever represented in Parliament and of five Scottish cities, but his bitter electoral disappointment at Dundee after fourteen and a half years as the local MP prevented him from adding Scotland’s fourth-largest city to that list.

Aberdeen

Not quite three years after his refusal to become a burgess of Dundee, Churchill happily acceded to the invitation of the Aberdonians. On 27 April 1946, Churchill Day, the city gave him a double-barreled welcome by granting him the Freedom of the City at the Music Hall followed by an Honorary LL.D. at the University’s Mitchell Hall. “Wherever he went…there was welcoming laughter and applause, and this swelled to a roar as he moved up in the procession through a packed audience which had waited long and patiently for his arrival.”

Churchill spoke at both ceremonies. At the Music Hall he said, “Aberdeen is also famed for warm hearts, keen affection and bright eyes. I am deeply moved by your welcome. I regard it as a special compliment to an Englishman to be invited to receive the Freedom of this City and a degree from its eminent University, and the generosity and kindness which you show me are a joy indeed.”

At the university, Professor T. M. Taylor, The Promoter in Law, recalled the observation of Edmund Burke that the ancient spirit, though not always visible, “never fails to come forth whenever it is ritually invoked, ready to perform all the tasks which shall be imposed upon it by public honour.” Professor Taylor then fixed Churchill’s role:

In that crisis of our fate, there was but one man who could perform the saving act of ritual invocation: it was his supreme service so to do. Under his leadership, the ancient antithesis between word and deed ceased to hold; great oratory took on the quality of action, and in an hour of defeat the speeches of Mr. Churchill were the equivalent of victory. They fused and integrated our people, raising them to the height of their destiny, till the nation felt itself to be one—one in the face of present peril, one also with the historic and heroic past.

Turning to the Vice-Chancellor, Taylor concluded:

I do not presume even in summary to assess the contribution which Mr. Churchill made to our final deliverance. That is a task which will occupy the commentators of the future. But this I will say: to-day, we stand—let us all realise it—in the presence of one of the great figures of history. No distinction which we or any other mortal may confer, can add one scintilla to the lustre of his renown; but we may ask to have the honour of entering in the album of our graduates, the name of the greatest living Englishman.

In response, Churchill rose to face what was described as “a tumult of ecstatic cheers” and told the audience:

The Promoter in Law said a great many things which it is not perhaps good for a man to hear—it is going beyond what he should know or think about himself. I have been profoundly touched by his words. I humbly trust that history may not dissent from some at least of the conclusions which he placed before you.

…

As you know I have never accepted the suggestion that it was I who roused the British nation. I had the great honour and blessing, as I must regard it, to be gifted with those forms of expression, derived from long Parliamentary practice, which enabled me to be the exponent of the feelings which surged through almost every man and woman from Land’s End to John O’Groats in those days when we stood alone against the most awful forms of tyranny which had ever been known among men.

Thus ended Churchill’s contribution to this very special Aberdeen occasion, which was followed by a procession of students chanting the traditional Scottish verses, “Better lo’ed ye canna be, Will ye no come back again.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.