Finest Hour 189

Churchill, the Admiralty, and Scotland

Churchill Barrier 1 built at Scapa Flow in response to sinking of HMS Royal Oak

October 4, 2020

Finest Hour 189, Third Quarter 2020

Page 26

By Robin Brodhurst

Robin Brodhurst is author of Churchill’s Anchor: Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound (Pen and Sword, 2000)

It was in Scotland that Winston Churchill was first offered the position of First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill, as Home Secretary, was staying with Prime Minister H. H. Asquith at Archerfield late in September 1911 and had been playing golf when the Asquith asked him “quite abruptly” whether he would like to go to the Admiralty. Churchill immediately responded that he would. The driving force behind this appointment was the need to impose on the Admiralty a Naval Staff, and the first choice had been Richard Haldane, a Scot, who had created an Army Staff at the War Office. Haldane, however, was by then in the House of Lords, and both Asquith and Churchill deemed it essential that the leader of such a high-spending department should be in the Commons, so Haldane gave way, although holding the view that it would have been better if he had gone to the Admiralty for a year, so as to impose the new Naval Staff, while Churchill held the War Office for that year and then went to the Admiralty.1

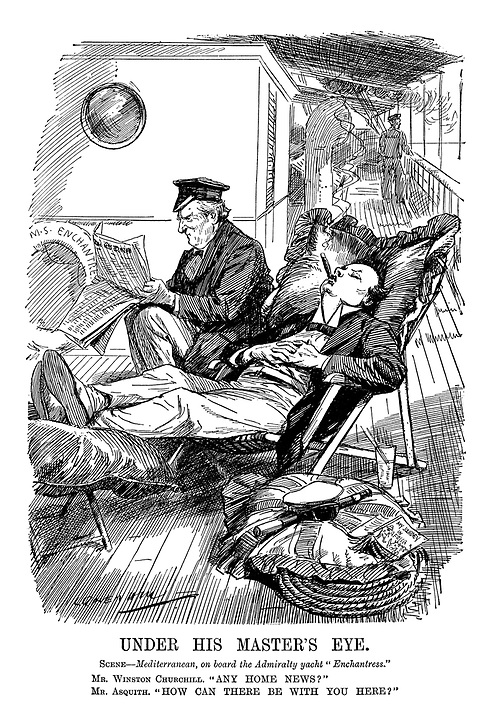

One of the greatest perks of the job of First Lord was the use of the Admiralty yacht Enchantress. She was a purpose-built yacht of 4000 tons, and Churchill used her extensively to visit both Royal Naval bases and fleets throughout his peacetime service as First Lord. In the three years that followed his appointment before war was declared, Churchill spent a total of eight months on board Enchantress. She had a crew of ten officers and 186 men and was a sister ship of the royal yacht Victoria and Albert. Churchill used her for two main purposes. The first, as mentioned, was to visit the Royal Navy, but just as important was to host politicians and friends. We tend to forget, in this age of instant communications via email and sat-phone, that earlier eras did not have that convenience, so Churchill would make a point of meeting politicians and others as he made a voyage by calling in at small ports, embarking them, carrying on his conversations and discussions, and then dropping them off at the next port. Much of this can be followed in his correspondence, as invitations are issued and arrangements are made.

In 1911 Churchill limited his visits on board Enchantress to the south coast. Enchantress, according to Admiral Fisher, was not a good sailor. He wrote to Churchill on 10 November 1911: “I confess I think it would be a good thing if I had a further talk with you and of course I should love the Enchantress (but not at sea!!!) She’s damnable at sea!”2 Churchill visited Portsmouth four times in November, usually for two nights at a time, once to escort the King and Queen out of Portsmouth harbour on their way to the Delhi Durbar and always to visit naval establishments. He did not, however, venture further than Portsmouth in those early months.

2024 International Churchill Conference

North to Scotland

It was not until the summer of 1912 that Churchill paid his first official visit to Royal Naval establishments in Scotland. He had visited Enchantress often in spring 1912, sometimes for a week at a time, but his longest trips in British waters were in August and September. He started on 19 August at Chatham, and worked his way up the east coast, via Sheerness, Harwich, Cromer, and Grimsby, before reaching Rosyth on 29 August. Here he inspected the dockyard before sailing to Dundee and St Andrews and then Cromarty, where he inspected Torpedo Boat Destroyers (TBDs) and submarines on 3 September.3 Enchantress then sailed to Aberdeen, where Churchill disembarked on 5 September, re-joining her two weeks later at Greenock on 13 September for a cruise among the islands of the Inner Hebrides on the west coast, calling at the Clyde shipyards, and then Lamlash on the Isle of Arran, Colonsay, Mull, Oban, and back to Greenock on 24 September. He returned south on Enchantress via the shipyards at Barrow-in-Furness and Birkenhead, and then Holyhead and Devonport, before disembarking at Portsmouth on 3 October. Among those who spent time on board during this period were Oliver Locker-Lampson (Conservative MP, who lived at Cromer); J. A. Spender (editor of the Westminster Gazette); Sir Edward Grey (the Foreign Secretary); Lord Morley (Lord President of the Council), who joined at Newcastle and stayed until Aberdeen; and Lord Fisher, then a once and future First Sea Lord. On the southward journey Enchantress called at Criccieth to embark David Lloyd George, his wife, and daughter for a day’s cruise.

Much of Churchill’s interest in Cromarty and Scapa Flow was in their defences (as well as those of Hull) since these were likely to be threatened in any war against Germany. There had been discussion in Cabinet on Cromarty and Scapa Flow in July. Churchill was adamant, having “spent a week in this wonderful natural harbour,” that Cromarty was “incomparably the finest [harbour] on the East Coast of Great Britain.”4 He was determined that it should have a floating dock and floating work shops so as to maintain and repair heavy ships, as well as defensive batteries, expecting the Treasury to pay up without question. Churchill far preferred Cromarty to Rosyth as a base, writing a Memorandum for the Naval Staff on 5 October explaining that “a fleet leaving Cromarty comes almost immediately into the open sea, instead of having to make its way down 17 or 18 miles of difficult channel, affording many opportunities to mines and submarines…. The docks and dredged channel at Rosyth cannot be counted upon for 4 years; the temporary base at Cromarty could be brought into existence in 6 months.”5 Given the close proximity to the bright lights of Edinburgh, it was not wholly surprising that many Royal Naval officers preferred Rosyth!

At War

The summer of 1914 was busy, and Enchantress was fully used, as in 1913. As far as can be seen from her log, she was confined to the South Coast, with trips across the channel to Cherbourg and Dieppe. There had been plans for Churchill to visit both the Russian navy at Kronstadt and the German navy at Kiel in June, but although the visits by the Royal Navy did go ahead, Churchill did not accompany them. All that is certain is that he did not visit Scotland at this time.

Once war was declared on 4 August, Churchill remained at first in London before his odyssey to Amsterdam. There was as far as can be traced only one visit to Scotland, which is not mentioned in either the Official Biography or The World Crisis. In The Gathering Storm, however, Churchill recalls visiting the Fleet at Scapa Flow and Loch Ewe in September 1914 and staying with Admiral Jellicoe so as to visit many ships and meet most of the senior officers. His concentration was firmly fixed elsewhere, initially on Amsterdam, and then on the Dardanelles. This is in contrast to 1939, when he was appointed to the Admiralty on 3 September and immediately visited the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow on 15 September.

Churchill’s first visit to the Fleet during the Second World War is well documented. He left London by train late on 14 September and arrived at Wick the next morning, transferring to Scapa and the flagship of the C-in-C, Admiral Sir Charles Forbes, HMS Nelson. Here Churchill discussed the naval situation and the safety of the anchorage, which had been a matter of considerable discussion in Cabinet before, on the 17th sailing to Loch Ewe, on the west coast, where most of the Fleet lay at anchor. Nelson, to Churchill’s surprise, had sailed without an escort because there were not enough destroyers. Churchill reflected that most of the senior officers in the previous conflict had been appointed by him, whereas the present senior officers had all been junior officers in 1914–15 and were mainly unknown to him.6 The problems, however, all seemed much the same. The principal problem was that Scapa Flow, while the right place to control the northern exit from the North Sea, was not yet safe from attack by U-boat. It had not been safe in 1914 and again was unsafe in 1939. The defences had been starved of money between the wars, like so much else. He stayed a second night on board Nelson, disembarked on the 18th, and drove back to Inverness. On his return to London from Inverness, Churchill was met by the First Sea Lord, to be informed that one of the Royal Navy’s seven aircraft carriers, HMS Courageous, had been sunk in the Bristol Channel. It was to be closely followed by another disaster, this time in Scotland.

The poor defences of Scapa Flow received their greatest blow in October 1939. Churchill had repeatedly warned that the defences were not secure and he was proven right, when, at one o’clock in the morning of 14 October, Germany’s U-47 torpedoed HMS Royal Oak, with the loss of 839 lives. In the First World War there had been two attempts by U-boats to enter the anchorage. Both had been defeated. Now, at the first attempt, Kapitänleutnant Gunther Prien, commanding U-47, managed to achieve his great success. Churchill was appalled. As his daughter Mary later said, “[He] felt the loss of life very much. He realised what it all meant, the loss of the great ship, the loss of the men—and what it meant in terms of the war.”7

It was not until well into the New Year that the First Lord managed another trip to see the Home Fleet in Scotland. Churchill departed from London by train on the evening of 6 March and arrived in Glasgow the next morning. On 7 March, he embarked on board Forbes’s flagship and accompanied the Fleet through the Minches and back to its anchorage at Scapa Flow, which was now considered safe, and where they would meet those parts of the Home Fleet that had been based at Rosyth during their absence from Scapa. Churchill paints a marvellous picture in The Gathering Storm of their voyage by day and night through these restricted waters, explaining that the waters were narrow and intricate, requiring exact navigation by the Master of the Fleet, the navigating officer of the flagship. Just as they were about to depart at lunch time, this officer was struck down ill, and so “a very young-looking lieutenant who was his assistant came up on to the bridge to take charge of the movement of the Fleet. I was struck by this officer, who without any notice had to undertake so serious a task requiring such perfect science, accuracy and judgement. His composure did not entirely conceal his satisfaction.”

Churchill’s passage to Scapa Flow was interrupted by an air raid on the anchorage, which dropped mines on the main entrance, forcing Forbes to delay his entrance for twenty-four hours while they were cleared. The delay not being acceptable due to his needing to return to London, Churchill was transferred to a destroyer in a cutter, rowing the mile between ships, and taken into Scapa Flow by what the commanding officer of the destroyer referred to as “the tradesmen’s entrance,” the Switha Sound.8 Churchill soon found his way on board HMS Hood, where he was entertained by Admiral Whitworth, commanding the Battle Cruiser Squadron, spent the night, and inspected ships and the new defences the next day. He caught the night train to London on the evening of 10 March and, once back at the Admiralty, issued a clutch of minutes reflecting all that he had discussed with both Admirals Forbes and Whitworth. Churchill reported to the Cabinet that he considered the Scapa Flow anchorage to be 80% secure, and that “the German aircraft, which… had been seen dropping objects in one of the entrances to Scapa had been mistaken for our own machines which had been co-operating with the defences for training purposes at the time,” a useful lesson for future avoidance of friendly fire incidents.9

Within days Churchill was caught up first in the planning, and then in the implementation of the Norway campaign, so he had no time to visit Scotland, let alone any other Royal Naval establishment. On 10 May he became Prime Minister and left the Admiralty. As Prime Minister he was to make many journeys to Scotland, both to embark for trans-Atlantic voyages to meet President Roosevelt and to visit Royal Naval facilities, but above all to visit Combined Operations training establishments, which were often based on the west coast of Scotland. Here he could see active preparations being made for the sort of operations he so dearly loved. Scotland, and its Royal Naval ports and bases, were close to the heart of Churchill, and he visited them as often as he could.

Endnotes

1. Randolph S. Churchill, Winston S. Churchill, Vol. II, Young Statesman, 1901–1914 (London: Heinemann, 1967), pp. 538–39.

2. Lord Fisher to Churchill, 10 November 1911, in Randolph Churchill, ed., Winston S. Churchill, Companion Volume II, Part 2, 1907–1911 (London: Heinemann, 1969), p. 1327.

3. TBDs were the early version of destroyers with the initial purpose of defending the battle fleet from attack by torpedo boats.

4. Churchill to Lord Haldane, 26 September 1912, in Randolph Churchill, ed., Winston S. Churchill, Companion Volume II, Part 3, 1911–1914 (London: Heinemann, 1969), p. 1649.

5. Ibid., Churchill memorandum, dated 5 October 1912, p. 1652.

6. Forbes had in fact served at the Dardanelles in 1915 as executive officer on board the flagship HMS Queen Elizabeth before being appointed Flag Commander to Jellicoe. He remained in the Grand Fleet until the end of the war, ending as Captain of HMS Galatea.

7. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Vol. VI, Finest Hour, 1940–1941 (London: Heinemann, 1983), p. 62.

8. Commander J. T. Lean, commanding HMS Punjabi.

9. Minutes of the War Cabinet, Martin Gilbert, ed., The Churchill War Papers, Vol. I, At the Admiralty, September 1939–May 1940 (London: Heinemann, 1993) pp. 867–68.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.