Finest Hour 176

The Fabulous Leonard Jerome: Churchill’s “Fierce” American Roots

August 28, 2017

Finest Hour 176, Spring 2017

Page 10

By Paul J. Taylor

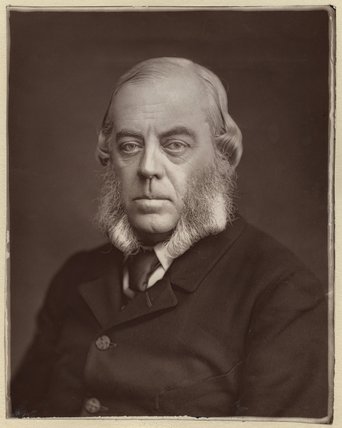

Winston Churchill once observed about a photo of his grandfather Leonard Jerome that he was “very fierce.” “I’m the only tame one they’ve produced,” he said modestly.1 Jerome, like his grandson, spent a lifetime beating the odds.

Despite an historic disdain for hereditary aristocracy, Americans love to create their own—if transitory—nobility. They are the wealthy, stars, glamorous, or notorious. Leonard Jerome was all that and more: he was a feisty, flamboyant, ultra-wealthy investor, sportsman, diplomat, raconteur, and arts patron. He easily made fortunes and easily lost them. His friends were a “Who’s Who” of the nouveau riche elite, and by age forty his informal moniker was “The King of Wall Street.”

Jerome’s life started humbly in 1817: he was one of ten children who tended chickens and other livestock on father Isaac’s farm in Palmyra, New York. Arriving in Palmyra at the same time was the family of a young Joseph Smith, who went on to found the Mormon church. The Jeromes had their own religious antecedents. Their French Huguenot forebears immigrated in 1710.

At age fourteen, Leonard toiled in a store, where he learned to haggle. He followed brothers to Princeton University, but, struggling with math and expenses, he transferred to and graduated from the less expensive Union College in Schenectady, New York. He then studied law and started a practice before an entrepreneurial spirit led him to found a newspaper and printing business. Both succeeded thanks to his shrewd management and hard-hitting political editorials.

2024 International Churchill Conference

The adult Jerome was a witty, charming, handsome, and extroverted civic leader. Hostesses vied to have him at social events. He met Clarissa (Clara) Hall, heiress to a small fortune, at a ball and fell in love. They married in 1849. Winston Churchill loved to brag that both his maternal grandparents had American officer ancestors in the Revolutionary War.

Opportunity Knocks

A knack for profitmaking led Jerome to New York City in 1850, where he and brother Lawrence invested and helped run an early telegraph enterprise. It flourished and rapidly sold for a big profit. Thus started a classic Horatio Alger story.

The Jerome brothers loved New York, America’s fastest growing commercial center and transportation hub. Vast opportunities were there, even as the city struggled with the problems of explosive growth. Jerome dove into the untamed waters of 1850s Wall Street stock speculation. His talents perfectly matched that world, and his intelligence and quick wit at late-night stag parties boosted his reputation. He surprisingly declared bankruptcy for a few weeks before establishing a lifelong pattern of rebounding and prospering.

In 1852, Clara gave birth to their first child, Clarita, and Jerome accepted President Millard Fillmore’s nomination as American consul to Trieste, a popular summer destination for nobility. He served for only eighteen months, long enough for Clara to be mesmerized by European society. Her fascination ultimately changed the Jeromes, Churchills, and world history.

A Midas Touch

Returning home, Jerome formed a stock brokerage partnership with his brother. They cunningly hosted posh lunches for editors and planted tips for publication about stocks they owned. Jerome’s wealth skyrocketed, estimated at ten million dollars at a time when New York had fewer than twenty millionaires.

Jerome became a patron of the arts, especially opera. He loved more than the music. He had a passion for female opera stars. His dalliances were often public. Rumors still abound about him and superstar Jenny Lind, the “Swedish Nightingale.” A carnal liaison cannot be proven, but Lind said Jerome was “the best looking” of her fans.2 When Clara became pregnant, Leonard suggested they name the baby “Jenny.”3 The child, born in 1854, was named Jeanette but called “Jennie.” A third daughter, Camille, was born in 1855 but died at age eight.

Winston Churchill’s American grandparents

Top: Leonard Jerome

Bottom: Clara Hall

Images courtesy of Randolph Churchill

A competition started in the mid-1850s to build lavish mansions. The Jeromes set the pace. Jennie’s childhood home was an opulent palace. Ballroom fountains could flow with champagne, and it had a 600-seat opera theater, a 100-guest dining room, a breakfast room for seventy, and a carriage house with elegant paneling and stained glass windows. Their horses lived better than most New Yorkers.

The Jeromes’ social ambitions were equally outsized. They entertained lavishly. Churchill said, “My grandfather thought nothing of spending $70,000 on a party, where each lady found a gold bracelet, inset with diamonds, wrapped in her napkin.”4

Needing another break, Jerome took the family to Paris in 1858, living sumptuously on the Champs-Elysees. Rich Americans were welcome at the Court of the Emperor Napoleon III, transfixing Clara. During the visit, their fourth daughter, Leonie, was born.

Turbulent Times

During the Civil War, Congress passed a mandatory military draft in 1863. Working-class New Yorkers rioted, killing blacks and burning entire blocks. Although the Jeromes owned about a quarter of the New York Times, Leonard was never its majority owner nor editor, as often claimed. But he was no passive investor. When the pro-Lincoln newspaper was targeted by rioters, Jerome joined other investors behind Gatling guns to protect the paper’s offices.

The war was a jackpot for Jerome. Receiving coded telegrams from the frontlines, he used the inside news in aggressive stock trading. Explosive growth in industry and railroads was also a boom. But his biggest asset was “an almost blind risk taking” rooted in “a complete confidence in his own destiny.”5 Still, he wisely created trusts for Clara’s future.

Gossip about Jerome’s adulteries abounds. In addition to Lind, liaisons included singers Adelina Patti and “Fanny” Ronalds. Then there was “Minnie” Hauk, allegedly his illegitimate child. Born about the time of Lind’s visit, she resembled daughter Jennie. Clara and Leonard took Minnie into their home, and she totally depended on them before rising to stardom as an opera singer.

Stories of serial philandering and illegitimate children may sound like rumormongering. But when Clara and Leonard’s longtime mistress Fanny came face-to-face, Mrs. Jerome said, “My dear, I understand how you feel. He is so irresistible.”6

Thoroughbred horses were Leonard’s other love. He founded the American Jockey Club and, with August Belmont, Jerome Park racetrack—home to the first Belmont stakes. Leonard made racetracks acceptable for the social elite. He became known as the “Father of the American Turf.”7 Jerome Park vanished in 1894, yet a namesake remains. Jerome had built a road to the track, but the city named it after a politician, infuriating Clara. She replaced the signs with her own: Jerome Avenue, one of the largest streets in the Bronx.

Clara Lives Her Dream

The family’s world turned upside down in the late 1860s. They moved to Paris. Biographers suggest many reasons. William Manchester points to Clara’s love of Paris and fascination with the Second Empire.8 Others speculate that Leonard’s adultery embarrassed Clara in New York society.9 Anita Leslie claims that Clara persuaded Leonard to go for two years, but a stock market crash intervened. All are possible, but most agree that Europe drew Clara like a moth to a flame. Since they remained a couple with frequent letters and regular visits, it is likely that Clara simply loved Europe, and Leonard indulged her. The fact is he went home, and his family stayed.

Jerome’s fortunes took a hit with the 1868 Black Friday crash, which began when gold speculators (not Leonard) tried to corner the market and artificially increase values. President Grant halted the plot, but shock waves affected markets for years. Jerome responded by giving up his mansion and restructuring other assets. His fortune reputedly halved, but the real impact is unknown. The family continued living high nonetheless.

Likely the Jerome women were oblivious. Clara and the three daughters had every luxury. Each repeatedly ordered outrageously expensive gowns by the dozen from Paris designers. Leonard remarked of Clara, “She hates money, or thinks she does. I’ve never discussed business matters with her.”10

Clara was obsessed with their standing in society. Daughter Clarita debuted at the Tuileries Palace. Jennie’s planned debut in 1870 was upset by Germany’s crushing victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the exile of the last French monarch.

New America and Old England

The family bolted to a stylish resort on the Isle of Wight. They quickly became popular guests at swanky events, including a shipboard gala where Jennie was introduced to Lord Randolph Churchill. Randolph told a friend that night that he would marry Jennie. She just as quickly caught the marriage bug. They were engaged three days later.

Both families were aghast. Whirlwind engagements were taboo. Randolph wrote for approval from his father, the Duke of Marlborough, who responded, “From what you have told me & what I have heard, this Mr. J seems to be a sporting, and I should think, vulgar kind of man. It is evident he is of the class of speculators, he has been bankrupt once; and may be so again.”11 The Duke said they should wait. His headstrong son would not.

Jerome represented the New American class of self-made men, while the Churchills were the Old England of inherited wealth that disdained work. Jennie’s father was opposed to the marriage at first. Then he warmed to it, only to change his mind, possibly because the Duke inquired about him through the British embassy.

Randolph broke the logjam with his election to Parliament and then getting the Prince of Wales to endorse the marriage. The Prince had once been guest of honor at the Jerome Mansion. Clara and Jennie pressured Leonard. He relented.

The final roadblocks were money and control. Jerome’s negotiating shattered tradition. He was willing to be more generous than the Duke, but insisted Jennie have her own income. This modern notion shocked the Duke. A compromise a week before the wedding had Randolph’s debts forgiven, and sums given by both families to assure annual incomes. Half of one trust’s income was for Jennie’s personal use. Jerome had won.

The 15 April 1874 wedding was the season’s top social event. And none too soon. Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was born 30 November 1874, 272 days after the couple had last seen each other. “Premature birth” was the official announcement, but was Jennie pregnant at the wedding? Who knows? When asked, Winston would playfully respond, “Although present on the occasion I have no recollection of the events leading up to it.”12

Meanwhile Jerome tended business in New York. He and Clara exchanged visits, and he constantly pleaded for news. Their other daughters also married into prominent British families. In 1881 Clarita wed Moreton Frewen from an ancient but poor family. Jerome liked the captivating groom at first, but Moreton was a squanderer whose money-making schemes always failed, enraging his father-in-law. Frewen’s nickname became “Mortal Ruin.”

Youngest daughter Leonie married more safely in 1884. Her husband Sir John Leslie was an Army officer and the son of an Irish baronet with estates covering 70,000 acres. Leonie’s daughter Anita became a chronicler of family history.

Jerome was enchanted by his grandchildren, “despite the strange English upbringing which made them seem reserved and different from the boys of his own recollection.” When he heard the emphasis on “gentlemanly birth,” he wrote: “The character of a gentleman I consider within the capacity of all—at least it requires no extraordinary intellect. A due regard for the feelings of others is in my judgment its foundation.”13

News that young Winston “seemed backward,” with poor school reports, led Jerome to counsel, “Let him be. Boys get good at what they find they shine in.”14

“Pass it On.”

By the 1880s, Jerome’s health flagged and so did his finances. He devoted more time to thoroughbred horses than to business. A contemporary account of him provides this description: “…The large, tall bony figure is attired in loose-fitting, old-fashioned black frock coat…the face bronzed by exposure to the weather…the hair iron gray….Once he dominated Wall Street as Jay Gould does now; but his was a merry despotism, and he was loved where Jay Gould would be hated.”15

Jerome gave up business entirely by 1888. His wealth had gone to family. He lived in a hotel, contentedly monitoring his racehorses. Clara’s letters expressed concern about his health, but he always said he was fine. He was not. He agreed to go to England to be cared for and left America a final time in December 1889. His daughters were shocked by his “tired and worn” look.16 His health faded, evidenced by a hacking, bloody cough. His grandchildren were told he had “galloping consumption” (virulent tuberculosis).17 Now an invalid, he was eventually taken to Brighton on the chance that sea air might help.

Leonard Jerome died on 3 March 1891, surrounded by his family. He told them on his deathbed, “I have given you all that I have. Pass it on.” His body was returned to America and entombed in a huge mausoleum—paid for years before—at the Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. His wife Clara and their daughter Camille are also buried there.

“Pass it on” can be interpreted many ways. But Jerome’s greatest legacy already had been “passed on” to his grandson Winston Leonard. Daily Mail war correspondent George Steevens once opined about Churchill: “He is what he is by breeding. From his father, he derives the hereditary aptitude for affairs….From his mother’s side… came the shrewdness, keenness, personal ambition, and sense of humor.”18

Jerome would have taken pride in his grandson’s world leadership and the fact that he actually earned a living by his wits as a journalist. A Nobel Prize for Literature and Number 10 Downing Street are a far cry from tending chickens in Palmyra.

Paul J. Taylor of Hingham, Massachusetts, is an author, a consultant, and a longtime member of the International Churchill Society. He is a distant cousin of Winston Churchill.

Endnotes

1. Michael Shelden, Young Titan: The Making of Winston Churchill (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), p. 36.

2. Anita Leslie, The Remarkable Mr. Jerome (New York: Henry Holt, 1954), p. 30.

3. Ibid.

4. William Manchester, The Last Lion, Winston Spencer Churchill, Visions of Glory, 1874–1932 (Boston: Little Brown, 1983), p. 101.

5. David Lough, No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money (London: Picador, 2015), p. 14.

6. Manchester, p. 99.

7. Leslie, p. 7.

8. Manchester, p. 98.

9. Lough, p. 15.

10. Leslie, p. 156.

11. Lough, p. 20.

12. Manchester, p. 50.

13. Leslie, p. 273.

14. Ibid., p. 304.

15. Ibid., 265.

16. Ibid., 307.

17. Shane Leslie notes from Leslie family papers possessed by Tarka King, Anita Leslie’s son.

18. Leslie, p. 304.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.