Finest Hour 187

The Seventh Duke of Marlborough

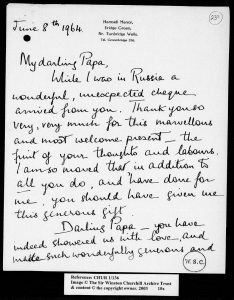

Lord Derby's Cabinet, 1867 - The Seventh Duke of Marlborough (seated at the table with head in hand) Lord Derby (standing with hand on despatch box at the right)

April 27, 2020

Finest Hour 187, First Quarter 2020

Page 14

By Fred Glueckstein

Fred Glueckstein is a frequent contributor to Finest Hour and author of Churchill and Colonist II (2015).

John Winston Spencer-Churchill was born on 2 June 1822 at Garboldisham Hall, Norfolk. He was the eldest son of George Spencer-Churchill, the sixth Duke of Marlborough, and Lady Jane Stewart, who was the daughter of the eighth Earl of Galloway. From his birth until the death of his grandfather—the fifth duke—in 1840, John held the family courtesy title Earl of Sunderland. This changed when he became first in line to succeed to the dukedom and was raised to the courtesy title Marquess of Blandford.

John Spencer-Churchill was educated at Eton and then Oriel College, Oxford. He served as a lieutenant in the 1st Oxfordshire yeomanry in 1843. On 12 July of that same year, he married Lady Frances Anne Emily Vane, eldest daughter of the third Marquess of Londonderry.

The young Spencer-Churchills had eleven children. Their third son, Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill, was born in London at 3 Wilton Terrace, Belgravia on 13 February 1849. Lord Randolph would become the father of Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill.

2024 International Churchill Conference

A Member of Parliament

Until he became the Duke of Marlborough in 1857, John was eligible to serve in the House of Commons. In 1840, he took his seat as the Conservative member for Woodstock in the parish of Blenheim, essentially the family “pocket borough.”

As a result of supporting Free Trade measures without the agreement of his father, whose influence at Woodstock was vital to his son, John was forced to relinquish his position as an MP and accept the stewardship of the Chiltern Hundreds on 1 May 1845. “Taking the Chiltern Hundreds” is the legal fiction used to resign from the House of Commons. Since members of parliament are technically not permitted to resign, they are instead appointed to an “office of profit under the Crown,” which requires MPs to vacate their seats.

In 1847, John was again elected for Woodstock and held that post until succeeding his father as duke in 1857. During his time in the Commons, he was best known as the author of the “Blandford Act” of 1856. The purpose of the act was to strengthen the Church of England in large towns by the “subdivision of extensive parishes, and the creation of smaller vicarages or incumbencies.”

The Seventh Duke of Marlborough

The sixth duke died on 1 July 1857, and John thus became the seventh Duke of Marlborough. He left the Commons for good and entered the House of Lords. He was later described by a biographer as “a sensible, honourable, and industrious public man.”1

Lord Randolph’s wife Jennie Jerome, Winston’s mother, remembered her father-in-law in her memoirs: “He had always been most kind and charming to me. If he seemed rather cold and reserved, he really had an affectionate nature. Although his children were somewhat in awe of him, having been brought up in that old-fashioned way which precludes any real intimacy, they were devoted to him.”2

The Duke performed various duties of political importance. As Prime Minister, Lord Derby appointed him Lord Steward of the Household in 1867. The position then carried Cabinet rank and so the Duke became a member of the Privy Council. The following year, and until December 1868, Marlborough served as Lord President of the Council. It was also in 1868 that Queen Victoria made the Duke a Knight of the Garter.

Viceroy of Ireland

When Benjamin Disraeli became Prime Minister in 1874, Marlborough was offered but declined the position of Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Two years later, however, he accepted the same position when the cunning Prime Minister saw it as an expedient to defusing a potential crisis. The Duke’s son Lord Randolph had foolishly threatened the Prince of Wales in a social scandal involving the Duke’s eldest son and heir. Sending the Spencer-Churchill clan to Dublin with the Duke as Viceroy and Lord Randolph as his secretary allowed for a necessary “cooling off” period to take place.

On 28 November 1876, Marlborough officially succeeded the Duke of Abercorn as the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, a position often more generally referred to as that of Viceroy. The Times reported the Duke’s arrival in Dublin on 13 December:

His Grace the Duke of Marlborough arrived at Kingstown this morning from Holyhead by the mail steamer Connaught. Although the weather was bitterly cold, and there was no shelter on the landing pier from a piercing wind, blowing from the north-west, a number of people assembled to see the new Viceroy, and awaited his arrival with exemplary patience. The steamer was three-quarters of an hour late, having been detained at Holyhead by a delay of the mail train.3

The Times told readers that the Duke, accompanied by Lord Randolph, was met on the landing by dignitaries and members of the Viceregal Staff. Taken to Dublin Castle, the Duke was received by the Lords Justices and Privy Council and delivered the Letters Patent of the Queen appointing him to the office of Lord-Lieutenant.

Young Winston and His Grandfather

In Dublin, the Duke and Duchess lived at Viceregal Lodge in Phoenix Park. Lord Randolph with his wife Jennie and young son Winston lived nearby in the Little Lodge. The Churchill family grew when Winston’s brother John Strange Spencer-Churchill was born at Phoenix Park on 4 February 1880.

In his autobiography My Early Life, Winston Churchill wrote that his earliest memories were of Ireland. One of his “clear and vivid impressions of some events” was of his grandfather, the Duke: “I remember my grandfather, the Viceroy, unveiling the Lord Gough statue in 1878. A great black crowd, scarlet soldiers on horseback, strings pulling away a brown shiny sheet, the old Duke, the formidable grandpapa, talking loudly to the crowd,” wrote Churchill. He added, “I recall even a phrase he used: ‘and with a withering volley he shattered the enemy’s line.’ I quite understood that he was speaking about war and fighting and that a ‘volley’ meant what the black-coated soldiers (Riflemen) used to do with loud bangs so often in the Phoenix Park where I was taken for my morning walks. This, I think, is my first coherent memory.”4

While her husband served as Viceroy, Winston’s grandmother instituted a relief fund to help avert the effects of the 1879 Irish famine. For her efforts, she was invested as a Lady of the Royal Order of Victoria and Albert by Queen Victoria. The family’s time in Ireland ended with Disraeli’s defeat in the general election in 1880. The Duke’s administration was considered popular and had worked hard to benefit Irish trade.

Upon his return from Ireland, the Duke resumed his work as president of the Shipwrecked Fishermen and Mariners’ Royal Benevolent Society, for which he served many years from 1858 to 1883. The Society, a national charity founded in 1839, provided help to former merchant seamen and fishermen as well as their widows and dependents.

The Duke made his last public appearance on 28 June 1883. It was a speech in opposition to the third reading of the Deceased Wife’s Sister Marriage Bill allowing a man to marry his dead wife’s sister. Parliament did not pass such an act until 1907, long after the Duke’s death.

At age sixty-one, the seventh Duke of Marlborough suddenly died in London of angina pectoris on 4 July 1883. After lying in state at Blenheim Palace, he was buried in the private chapel on 10 July. Winston Churchill was just eight years old when his paternal grandfather passed away. His early recollections of him in Ireland, however, would always be cherished.

Endnotes

1. George Clement Boase, “Seventh Duke of Marlborough,” Dictionary of National Biography, vol. X, 1885–1900 (London: Smith, Elder, 1902).

2. Ralph G. Martin, Jennie, The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill, vol. I, The Romantic Years, 1854–1895 (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1969), p. 165.

3. The Times, 13 December 1876.

4. Winston S. Churchill, My Early Life (New York: Touchstone, 1996), p. 1.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.