Finest Hour Extras

What Killed Lord Randolph Churchill?

Lord Randolph Churchill © National Trust, Chartwell; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

December 30, 2021

By Andrew W. Ellis

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill, father of Sir Winston Churchill and a major political figure in his own right, died at home in Grosvenor Square, London, on Thursday 24 January 1895. He was forty-five years old and had been unwell for some time. Lord Randolph’s wife, Lady Jennie Churchill, was present at the death, as were his mother, the Dowager Duchess of Marlborough, and his sons Winston and John. The fact of the death was communicated quickly to Queen Victoria, the Prince and Princess of Wales, the Prime Minister and other leading figures. [1] Recalling the moment of his father’s death many years later, Winston Churchill wrote: “My father died … in the early morning. Summoned from a neighbouring house where I was sleeping, I ran in the darkness across Grosvenor Square, then lapped in snow. His end was quite painless. Indeed he had long been in stupor.” Winston had endured a difficult relationship with his father. He had hoped to serve alongside him as a Member of Parliament, but it was not to happen: “All my dreams of comradeship with him, of entering Parliament at his side and in his support, were ended. There remained for me only to pursue his aims and vindicate his memory.” [2]

During Lord Randolph’s final weeks, bulletins appeared in Britain’s two leading medical periodicals, the British Medical Journal and the Lancet. [3] His slow decline gave ample opportunity for The Times to prepare a lengthy obituary. It appeared the day after Lord Randolph’s death, extending across seven columns. The obituary summarised Lord Randolph’s childhood and early adulthood, including his spells at Eton and Oxford (where “he was said to have been a somewhat unruly undergraduate”), his marriage in 1874 and the birth of his two sons. It reviewed Lord Randolph’s “strange, meteoric career”, from his election as a Member of Parliament in 1874 to his appointment as Secretary of State for India in 1885, then Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons a year later. European perspectives were provided by correspondents from Paris, Berlin and Vienna. [4] Somewhat surprisingly, very few subsequent historians, including Winston Churchill, have made reference to the obituary. The possible reason for that will become apparent.

Lord Randolph had experienced a number of health problems during his adult life but The Times noted that he became increasingly unwell in early 1894 when his doctors had prescribed a period of complete rest. Lord Randolph decided that his complete rest would take the form of a trip around the world accompanied by Lady Jennie and a selection of servants. They also took a young doctor called George Keith, son of Lady Jennie’s gynaecologist, who was tasked with sending regular bulletins back to England. The party left England in late June of 1894. They journeyed to New York and Maine, then to Canada where they crossed to Vancouver on the Canadian Pacific Railway. After visiting San Francisco they continued on to Japan, Singapore and India. By the time they reached Bombay (Mumbai), Lord Randolph was in such poor health that Dr Keith was advised to bring him home as quickly as possible. They travelled through the Suez Canal to Alexandria in Egypt where Lord Randolph fell into a coma. He remained in a coma for much of the journey back through France to London where he arrived on 17 December 1894.

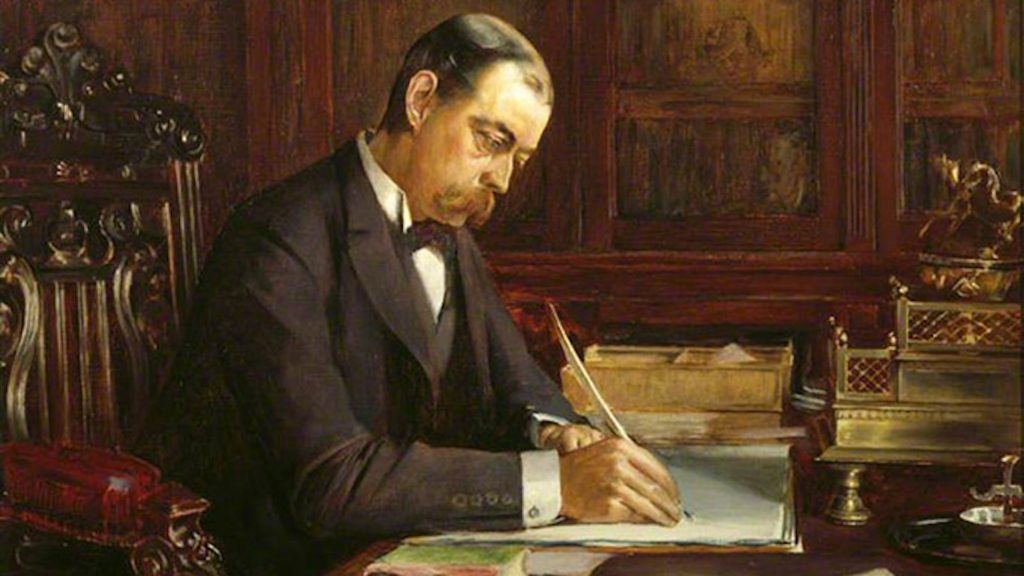

Dr Keith continued to be closely involved in Lord Randolph’s care, as did the family physician, Edward Charles Robson Roose, known as Robson Roose. Trained in medicine at Guy’s Hospital London, Roose began his career by setting up a practice Brighton, a fashionable health resort on England’s south coast. Roose attended to a number of wealthy patients when they were in Brighton. He moved to London in 1885 where he built up a practice catering to the rich and famous, including Prime Minister William Gladstone, cabinet minister Joseph Chamberlain and the Shah of Iran. [5] Roose combined a sympathetic bedside manner with a wide knowledge of medicine. He was physician to the Churchill family for many years, seeing young Winston through a serious bout of double pneumonia in 1886. Given the nature of Lord Randolph’s late ill-health, Roose regularly sought the advice of Dr Thomas Buzzard, one of Britain’s leading neurologists.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Back in London, Lord Randolph rallied from time to time but the nature of his illness was such that death was inevitable. It happened just five weeks after he returned to the capital. Large crowds watched his coffin pass through London en route for burial near the family home of Blenheim Palace. A memorial service at Westminster Abbey was attended by members of the establishment and politicians of all ranks and parties. Winston Churchill published a two-volume biography of Lord Randolph in 1906. That biography was Winston’s attempt to vindicate and come to terms with his late father. It focused on Lord Randolph’s political achievements rather than his character or his personal life. At the same time, a more personal memoir was published by Lord Rosebery, an old friend of Lord Randolph and a fellow politician. [6] More recent biographies have been written by Robert Rhodes James and Roy Foster. [7] Lord Randolph’s life is also discussed in many of the books on Winston Churchill and the Churchill family. [8] Biographies of Lady Jennie Churchill provide a different perspective, dealing more with Lord Randolph as a husband and father. [9]

General Paralysis

Lord Randolph’s death certificate gave the cause of death as “bronchial pneumonia from paralysis of the brain.” [10] That word “paralysis” had cropped up before, usually accompanied by the word “general”. On 19 January 1895, five days before Lord Randolph’s death, the Lancet published a short notice which said: “Lord Randolph Churchill’s condition during the last few days has generally been marked by an increase of cardiac weakness, with tendency to coma, interrupted by such occasional intervals of rallying and return to consciousness as are common in the advanced stage of general paralysis.” [11] The Times obituary observed that “The disease from which [Lord Randolph] suffered – general paralysis – had first seized him two or three years ago, and his trip round the world was undertaken in the hope that the change might tend to arrest its progress. This expectation was disappointed.” [12] The obituary ended with a statement from the Lancet which said: “No one knowing the conditions expressed by the term ‘general paralysis’ could have expected any other than the sad issue to his illness which took place early on Thursday morning”, adding: “Lord Randolph Churchill’s case has throughout been typical of general paralysis.”

The condition referred to on several occasions by theLancet and The Times is almost unknown today but was both familiar and feared in Victorian times. General paralysis first came to prominence in Paris early in the early nineteenth century when doctors began to encounter patients with a peculiar combination of “physical” and “mental” symptoms they had not seen before. They called the disease paralysie générale des aliénes which was translated into English as general paralysis of the insane then routinely shortened to general paralysis. In America the condition was known as general paresis (“paresis” meaning weakness). It was also referred to quite widely by the Latin name dementia paralytica (i.e., dementia with paralysis). The disease spread rapidly beyond Paris. By the mid nineteenth century cases were turning up regularly in hospitals and asylums across Europe. The first report of the condition in America came in 1843. Within a few decades, it had extended across the world. [13]

General paralysis was three or four times more common in men than women. Initial symptoms usually occurred between the ages of 30 and 50. The first “physical” symptom to appear was often a peculiar and highly characteristic fluttering of the tongue and lips that was typically combined with problems articulating words. Wider facial paralyses could occur. Progressive loss of power in the arms and legs was often accompanied by loss of feeling (numbness) in the affected regions. Poor control of leg movements and numbness in the feet caused sufferers to develop a characteristic ‘slapping’ gait with the feet positioned wide apart. That could sometimes occur in the absence of psychological symptoms, when it was known as tabes dorsalis or locomotor ataxia. Shooting pains in the legs were another recognised symptom.

The “mental” symptoms of general paralysis were variable. Most dramatic were grandiose delusions: textbook writers took great pleasure in describing patients who declared themselves to be Napoleon Bonaparte or the King of the World. Such delusions were often accompanied by an exalted mood and a sense of boundless optimism. Neurologist William Gowers said that patients in the early stages of general paralysis had a tendency to “regard all things through rose-coloured spectacles”. [14] Other patients experienced fear and a feeling of persecution, convinced that they were being hunted and in mortal danger. An early sign of cognitive decline was that patients struggled to recall the words they needed in conversation. Combined with poor articulation, that made their speech hard to understand. In the early stages, the symptoms often fluctuated, with patients having good days and bad days. As the disease progressed, rapid mood swings became common, with patients suddenly manifesting extreme rage for little reason and with no warning. Whatever the early psychological symptoms, all patients eventually declined into dementia accompanied by extreme weakness that left them immobile and largely unresponsive. That progression was predictable from the first lip fluttering or delusion. There was no escape: the disease was almost invariably fatal. At post-mortem, patients showed inflammation of the membranes (meninges) surrounding the brain and spinal cord combined with degeneration and loss of cells within those structures. [15]

Signs of General Paralysis in Lord Randolph Churchill

Keen to reassure the nation that Lord Randolph had received the best possible care, The Times obituary named five doctors involved in his treatment and diagnosis. Two of them were family physician Robson Roose and the young George Keith. The third was neurologist Thomas Buzzard who was based at the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptics in London’s Queens Square (now the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery). The Times described Buzzard as a man “who has made the nervous system a lifelong study”. His standing was such that when Lord Randolph’s condition became serious, Thomas Buzzard kept His Royal Highness Edward, Prince of Wales, apprised of the situation through correspondence with Sir Richard Quain, the Queen’s Physician Extraordinary.

The fourth doctor identified by The Times was William Gowers, a colleague of Thomas Buzzard at the National Hospital. Gowers was the author of Lectures on the Diagnosis of Diseases of the Brain and a two-volume Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System that was affectionately known within the National Hospital as “the Bible”. [16] William Gowers met with Buzzard, Roose and Keith on 10 January 1895 to discuss Lord Randolph’s condition. [17] For good measure, the four doctors then sought further confirmation of their diagnosis from Sir John Russell Reynolds, Professor of Medicine at University College Hospital, Fellow of the Royal Society, President of the College of Physicians, physician-in-ordinary to the household of Queen Victoria, and an expert on diseases of the nervous system. [18] The Times observed that between them, Buzzard, Gowers and Reynolds in particular “had a large acquaintance with cases exhibiting the varying phases of paralysis”. Importantly, they “entirely agreed in their diagnosis.” [19]

What was it about Lord Randolph Churchill’s illness that made Buzzard, Gowers and Reynolds so sure that he had general paralysis? The answer is that his last years he displayed both mental and physical symptoms that matched the textbook descriptions of the disease. Lord Randolph’s friend Lord Rosebery believed that the illness began in the early 1890s, when Lord Randolph was around forty years old. Lord Randolph routinely lived beyond his means. In 1891 his finances were in such a parlous state that he decided to travel to South Africa to invest in gold mines (and engage in a spot of game hunting). He borrowed money from Lord Rothschild who protected his investment by insisting that Lord Randolph should be accompanied by an experienced mining engineer. Thanks to the mining engineer, Lord Randolph was able to invest in mines that proved profitable. [20] With the benefit of hindsight, however, Lord Rosebery suspected that the quest for gold was the first indication of incipient general paralysis, saying: “Already, I think, the cruel disease that was to paralyse and kill him had begun to affect him.” Rosebery added: “The progress of the disease was slow at first, but its signs were obvious, and when it began his career was closed … There was no curtain, no retirement, he died by inches in public.” [21] Historian and Conservative politician Robert Rhodes James agreed, writing in his 1959 biography that “from 1891, Lord Randolph Churchill was a dying man.” [22]

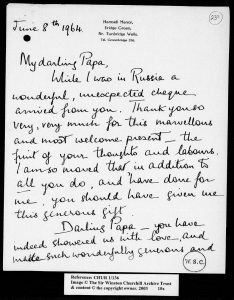

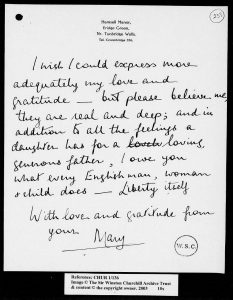

Lady Jennie Churchill met with Drs Buzzard and Roose in the summer of 1893 to express concern about her symptoms that now included poor articulation and intermittent numbness in Lord Randolph’s arms. When Lord Randolph heard about the meeting, he fired off an indignant letter to Thomas Buzzard. “I hardly ever had that numbness or difficulty of articulation”, he wrote, adding: “The only thing which has really troubled me & really might have made me ill is all this stupid gossip & fuss about my health.” That letter is dated 8 July 1893. The phrase “hardly ever” is an implicit admission that Lord Randolph had indeed experienced occasional numbness and difficulty with articulation. Despite his indignation, Lord Randolph agreed to a consultation. [23] Thomas Buzzard kept careful notes on all of his meetings with his famous patient. On Christmas Day 1894, when Lord Randolph was back to London, Dr Buzzard sat down to compile his notes into a single aide memoire. He observed that he had seen Lord Randolph back in 1885 but did not say what prompted that early meeting. In the summer of 1893, he had observed that Lord Randolph’s articulation was slurred and his tongue tremulous (as Lady Jennie had reported). Buzzard concluded that his patient “was in all probability commencing G.P.” (doctors’ shorthand for general paralysis). [24] Remarkably, Buzzard’s aide memoire survives, as does much of the correspondence from Lord Randolph’s last years between Lord Randolph, Lady Jennie, Robson Roose, Thomas Buzzard, George Keith and Lord Randolph’s mother, the Duchess of Marlborough. Those documents are held at the Churchill Archives at Churchill College, Cambridge and in the Thomas Buzzard Archive at the Royal College of Physicians in London. Many were reproduced in the first of a set of ‘companion volumes’ to the multi-volume biography of Sir Winston Churchill that was begun by his son, Randolph Spencer-Churchill, and continued later by historian Martin Gilbert.

In February 1893, a few months before his meeting with Thomas Buzzard, Lord Randolph rose to speak in the House of Commons. According to Robert James, members of parliament “were horrified in Churchill’s appearance. His white and prematurely aged face, shaking hands and dreadful articulation were too much for many, who quietly slipped out of the House.” [25] A year later, in March 1894, Lord Randolph lost his self-control during a Commons debate, screaming abuse at his own benches. An American acquaintance called Julian Osgood Field bumped into him in London. The two men discovered that they were headed for the same hairdresser. Field was shocked to see the change in Lord Randolph’s appearance, adding: “Once installed in adjacent chairs, the hairdresser made a casual remark about the weather. Lord Randolph flew into a rage, ordering the poor man to mind his own business.” Field was also shocked to see a change in the way Lord Randolph was walking. [26]

Lord Randolph gave his last speech to the House of Commons was in June 1894. Lord Rosebery described the event as “a waking nightmare”. [27] Another old friend, Wilfred Scawen Blunt, confided in his diary: “He is terribly altered, poor fellow, having some disease … which affects his speech, so that it is painful to listen to him.” [28] Lord Randolph took himself to health spas in Austria and Germany. On his return, he continued to address public meetings where audiences flocked to see him, expecting to bask in the witty, coruscating oratory of old. Now, though, in the words of Lord Rosebery, his audience “could no longer catch his half-articulated words, and soon went away in sorrow and astonishment.” Lord Randolph had a very different perception of his impact, declaring that he had never held such successful meetings. Rosebery believed that this lack of insight was itself “the hallucination of the disease”: in other words, Lord Randolph’s mistaken belief that his speeches were a great success was itself a symptom of his illness. [29]

In June 1894, Lord Randolph, Lady Jennie and Dr Keith embarked on their world tour. Several further symptoms of general paralysis manifested themselves during that tour. By August 1894, Lady Jennie was writing to her sister Leonie saying that Lord Randolph “is very kind and considerate when he feels well – but absolutely impossible when he gets excited – and as he gets like that 20 times a day – you can imagine my life is not a very easy one.” Dr Keith reported in September that he was quite unable to control his patient and in October that Lord Randolph was “one hour quiet and good-tempered, the next hour violent and cross.” Keith had to intervene at one point to prevent Lord Randolph attacking one of his valets. At the end of October, Keith wrote: “There is perhaps more loss of mental power, and his moods vary more quickly, at one moment irritable and silent and at another time talking and good tempered.” Keith also noted that his patient was experiencing fleeting delusions on a daily basis. [30]

In early August 1894, when Lord Randolph’s party was travelling across the Rocky Mountains, he suffered a new attack of a numbness. It was, said Dr Keith, “as bad as I have seen it.” Lord Randolph’s speech was also very poor. The numbness disappeared for a while but returned in October when his feet and hands were all affected. There was also a loss of power in his left hand. [31] Lord Randolph told his mother that he tackled the numbness by immersing his hands and feet in very hot water for prolonged periods of time. He claimed that Dr Keith was “highly relieved and confident” in the cure. Keith, however, made no mention of any therapeutic successes in his letters back to England, including his letters to the Duchess of Marlborough. Like his belief in the brilliance of his speeches, Lord Randolph’s assertion that his numbness was cured by hot water baths may have been an sign of lack of insight, combined perhaps with a desire to prevent his mother from becoming unduly alarmed. Lord Randolph’s handwriting became shaky and uncertain at around this time, with many corrections and crossings out. He blamed his poor handwriting on the unsatisfactory quality of the pen nibs available to him. [32] In late December, theLancet noted that paralysis had “rapidly declared itself during the last few months”, adding: “About four months ago … [Lord Randolph] was seized with transient paralysis of the left arm. Loss of power in other situations succeeded.” [33]

On 30 October 1894, Dr Keith wrote to Robson Roose from Singapore saying that Lord Randolph’s “speech is thicker and [he] has a tendency to use wrong words.” [34] On the same day, Keith wrote to the Duchess of Marlborough, saying that her son was becoming “very slowly and yet very steadily worse”. The following day he informed the Duchess that Lord Randolph “thinks he is quite well and will listen to no advice either from Lady Randolph or myself.” Lord Randolph told his mother: “I am very well.” The truth is that he was anything but well: the mismatch between his true condition and his perception of it was part of his illness. [35] By the end of October, Dr Keith was reporting “more loss of mental power”.

On 4 November Keith told Thomas Buzzard: “This has been the worst week since leaving home by a great deal. Lord Randolph has been violent and apathetic by turns … I notice a peculiar condition of the lower part of his face at times. The lower lip and chin seem to be paralysed, and to move only with the jaw … His gait is staggering and uncertain. Altogether he is in a very bad way … He cannot go on running down in the way he is doing, and last more that at the very outside, a few months.” [36] The decision was taken to fetch Lord Randolph home as quickly as possible.

The loss of mental power reported by Dr Keith in October 1894 continued. On New Year’s Eve, Sir Richard Quain, Physician Extraordinary to Queen Victoria, wrote to Thomas Buzzard on behalf of Edward, Prince of Wales, enquiring about Lord Randolph’s condition. [37] Buzzard replied: “As you are aware Lord Randolph is affected with ‘General Paralysis’, the early symptoms of which, in the form of tremor of the tongue & slurring articulation of words were evident to me in an interview two years ago … I think it likely, from what I have heard from members of the House of Commons, that the articulation difficulties may have been present something like three or four years. In Lord R’s case the physical signs – tremor, faulty articulations, successive loss of power in various parts of the frame have been much more marked than the mental ones which have hitherto been of comparatively slight character, grandiose ideas, however, not being absent at times & on some occasions violent of manner.” [38]

On 1 January 1895, when Lord Randolph was back in London, Thomas Buzzard described his patient’s condition as one of “mental feebleness”. [39] The progressive paralysis continued. Winston Churchill said that by the time his father reached England, he was “as weak and helpless in mind and body as a little child.” [40] Keith and Roose shared responsibility for Lord Randolph’s day-to-day care. Keith told Buzzard in mid-January that Lord Randolph had “been bad all day having one delusion after another”, adding: “He is much weaker today and seems to be sinking.” A few days later Keith reported that “Lord RC had an attack of acute mania last night lasting twenty minutes and another this morning for two hours”. After the second attack, Lord Randolph became completely comatose. Keith said simply: “Dr Roose and I agree that he is dying.” [41]

On 3 January 1895, Lady Jennie wrote to her sister Leonie: “Physically he is better but mentally he is 1000 times worse.” Lord Randolph had apparently been close to death. Lady Jennie said that “Even his mother wishes now that he had died the other day.” She continued: “Up to now the General Public and even Society does not know the real truth … it would be hard if it got out. It would do incalculable harm to his political reputation & memory & is a dreadful thing for all of us.” [42] Lady Jennie did not want the General Public or Society (meaning upper-class society) to learn of Lord Randolph’s weakness, staggering gait, rages, delusions and loss of mental power.

As the Lancet said, Lord Randolph’s case was typical of general paralysis as described in contemporary medical textbooks. Excitable behaviour, excessive optimism, rapid mood swings, delusions, a fluttering tongue, poor articulation, a short-lived facial paralysis, loss of power in the arms and legs with accompanying numbness, word-finding difficulties and lack of insight culminated in a final cognitive and physical decline. The Lancet added: “No one knowing the conditions expressed by the term ‘general paralysis’ could have expected any other than the sad issue to his illness which took place early on Thursday morning from rapidly increasing congestion of the lungs. All medical readers of the numerous bulletins reporting almost from hour to hour in the daily press the progress of his malady must have seen that the end was near, and latterly, despite the lingering course the terrible illness in question is wont to pursue, must have seen that the end was coming quickly. Lord Randolph Churchill’s case has throughout been typical of general paralysis.” [43]

The Disputed Cause of General Paralysis

Throughout the nineteenth century, many theories as to what might cause general paralysis were proposed. The Parisian doctors who first described it sought separate explanations for its physical and mental symptoms, but as it became increasingly clear that neurological damage could be responsible for both types of symptom, doctors began to search for a single explanation. Inflammation of the meninges and loss of brain substance evidently played a part, but what caused them to occur?

In 1857, two doctors working in Denmark called Friedrich von Esmarch and Peter Willers Jessen made the radical proposal that general paralysis was caused by chronic infection with the sexually-transmitted disease syphilis. That hypothesis gained some traction in Scandinavia but was largely rejected in the rest of Europe and North America. One problem was that doctors were often unable to find physical or documentary evidence of past syphilis infection in their general paralysis patients. Syphilis did not always leave lasting scars and both patients and their families would deny prior infection. A second problem was that general paralysis failed to respond to treatments like mercury and potassium iodide that had some success against syphilis. How, doctors argued, could general paralysis be caused by syphilis if the two diseases responded differently to the same medications? As a result, the majority of experts in the second half of the nineteenth century rejected the syphilis hypothesis, preferring to believe that general paralysis was caused by lifestyle factors. In his influential textbook Clinical Lectures on Mental Diseases, Edinburgh psychiatrist Thomas Clouston claimed that general paralysis could be triggered by bad liquor, a riotous lifestyle, promiscuous sexual indulgence, hard muscular labour, hard study, severe shocks, anxiety and eating meat (among other factors). He thought it possible that being infected with syphilis might predispose a patient to general paralysis but added: “I do not think there is any proof that [general paralysis] is syphilitic in origin.” [44] French psychiatrist Achille Foville wrote: “I may as well also mention the opinion expressed in 1857 by Jessen and Esmarch, that general paralysis is always and invariably of syphilitic origin. This assertion has … no supporters.” [45] In his Textbook of Mental Diseases (1897), T. H. Kellogg, former physician-in-chief at the New York City Asylum, blamed general paralysis on civilisation. Kellogg pointed in particular at “competition, reckless and feverish pursuit of wealth and social position, overstudy, overwork, unhygienic modes of life, the massing of people in large cities, the indulgence in tea, coffee, tobacco, stimulants, and social and sexual excesses.” [46]

Such opinions dominated in the UK. A week after Lord Randolph’s death, the British Medical Journal published one of a regular series of articles bringing its readers up to date on current thinking in relation to different medical conditions. On this occasion, the condition was general paralysis. (The timing of the article was probably not a coincidence.) The article said that while much about general paralysis remained obscure, “one factor is almost always to be traced, namely, hard work under conditions of excitement and responsibility.” [47] There was no mention of syphilis. The contribution from theLancet that appeared within The Times obituary embraced this view, saying: “Highly spirited and nervous by constitution [Lord Randolph] led an over-full life in every direction … being distinguished alike by his relentless tactics towards opponents and his irresponsible attitude towards friends, he drained to the very dregs the heady cup of politics … while he continued to double with the life … of the stormy statesman the life of the great nobleman and the man of pleasure, sport and fashion. Early success prompted him to over effort, a great and unexpected check caused him to redouble those efforts, and the result was to ruin his nervous constitution.” The Lancet added: “we believe that it will be a solace to his admirers to learn that during the end of his career the hand of sickness was upon him, so that in considering the claims upon their admiration they must in justice to the sound man neglect the failings of the sick man.” [48] This is important: at the time Lord Randolph Churchill died, established medical opinion rejected the notion that general paralysis was caused by syphilis, arguing instead that it was a consequence of lifestyle factors. Several recent commentators have failed to appreciate that crucial point.

The fact that when Lord Randolph died, general paralysis was blamed on overwork and lifestyle (rather than syphilis) explains why The Times and the Lancet felt able to be open about the diagnosis Lord Randolph’s doctors had unanimously arrived at. There is no way that the term general paralysis would have been deployed so freely if anyone believed that it would damage Lord Randolph’s reputation or impugn his memory. Shortly after Lord Randolph’s death, Sir John Russell Reynolds was made Baron Reynolds of Grosvenor Street while William Gowers was knighted in Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Honours List of 1897. That would not have happened if Queen Victoria and her advisors though that in publicly attributing Lord Randolph’s death to general paralysis, Reynolds and Gowers were declaring that the former Secretary of State for India, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons had in fact been syphilitic for many years.

Syphilis

Medical opinion only began to shift after Lord Randolph’s death. In an experiment that would absolutely not be permitted today, Austrian psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing demonstrated that if patients with general paralysis were deliberately inoculated with syphilis they did not develop symptoms, implying that they were already immune through having contracted the disease previously. That was in 1897. Within a few years, two major reviews were published, arguing that the evidence was moving in favour of syphilis as a major contributing factor if not the cause of general paralysis. The first came from the eminent German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin who concluded: “We must regard syphilis as the only essential cause of paresis [i.e., general paralysis].” The second came from British psychiatrist W. H. B. Stoddart who declared: “we may say for practical purposes that hardly anybody runs the risk of getting general paralysis who has not had syphilis.” [49]

The bacterium responsible for syphilis (Treponema pallidum) was identified in 1905. A test for syphilis antibodies was soon developed and found to be positive in a high proportion of patients with general paralysis, implying prior infection (however much the patients and their families might deny it). [50] Then, in 1913, Hideyo Noguchi and Joseph W. Moore reported finding Treponema pallidum in samples of the brains of patients who had died with general paralysis. The Times carried an account of Noguchi and Moore’s “important paper” in its issue of 13 August 1913, noting that the finding had already been replicated in laboratories in France, Germany and England. [51] Within a short space of time the debate was over. Esmarch and Jessen had been right after all: general paralysis was caused by chronic infection with syphilis which induced the inflammation of the meninges and the loss of brain tissue characteristic of the disease. The reason why general paralysis is so rare today is that when penicillin became widely available in the 1940s and 50s, it proved to be highly effective against syphilis. Penicillin can prevent infection from developing into general paralysis and can prevent early-stage general paralysis from progressing further. [52] Penicillin-based antibiotics remain the treatment of choice for syphilis.

We can now state categorically that if Lord Randolph Churchill died of general paralysis, it was because he contracted syphilis some years previously. The average time between being infected with syphilis and showing symptoms of general paralysis was ten to fifteen years. If Lord Randolph showed the first signs of general paralysis in about 1890, he probably contracted syphilis in the mid to late 1870s. We should really not be surprised if Lord Randolph acquired syphilis at some point. The disease was rife in Victorian England. William Gowers, one of the neurologists involved in Lord Randolph’s case, estimated that around one in ten of men in London from the “middle and upper classes” was infected. [53] Analysis of medical records for England and Wales found an infection rate of eight per cent for asymptomatic upper- and middle-class men in their mid thirties. [54] Lord Randolph was precisely the sort of impulsive risk-taker who was likely to contract syphilis. His own father once remarked that his “great faults [were] want of self control in his language, temper and demeanour and an imperiousness of disposition to those under him.” [55] Even when Lord Randolph was alive, there were rumours that he had syphilis. A friend and political colleague called Louis Jennings reputedly told journalist Frank Harris that Lord Randolph acquired syphilis as an undergraduate after a raucous evening in the company of fellow members of the notorious Bullingdon Club. The timing of that alleged incident which, if true, must have happened in about 1869, is a little early for the hypothesised time window, and the veracity of the story is debatable (to say the least), but it is not impossible. [56]

According to Lady Jennie Churchill’s biographer, Anne Sebba, some members of Lady Jennie’s family rejected the Oxford story, believing that Lord Randolph contracted syphilis from a chambermaid at the family seat of Blenheim Palace shortly after his marriage in 1874. Lord Randolph is known to have thought nothing of aristocratic men imposing themselves upon female members of staff: when the marriage of some friends of Lord and Lady Churchill was breaking up over the husband’s behaviour with female staff, Lord Randolph expressed amazement, asking: “What does one occasional cook or housemaid matter?”. [57]

American friend Julian Osgood Field said that syphilis began to cause Lord Randolph trouble soon after his marriage (which would fit with the Blenheim Palace theory). According to Field, Lord Randolph “was always willing, nay glad enough, to consult any specialist … [but] would never follow the treatment recommended.” That was not uncommon: the side effects of the anti-syphilitic treatments in use at the time – notably the mercury-based medications – were deeply unpleasant, including bad breath and loss of teeth. They were also tell-tale signs that a person was probably being treated for syphilis. Field was based in Paris. He described how Lord Randolph “came to see me in Paris, at my earnest entreaty, to see a famous physician” (mostly likely the celebrated syphilologist Alfred Fournier). Field plied Lord Randolph with a brandy cocktail to give him courage. When they arrived at the doctor’s practice, they found the waiting rooms to be full. Field tipped a manservant to allow Lord Randolph to wait discretely in the kitchen. He left Lord Randolph alone for a moment only to discover on his return that his friend had fled down the servants’ staircase. Field hauled him back. The specialist inspected Lord Randolph and gave him prescriptions and a warning as to what could happen if he did not take the medication and mend his ways. Lord Randolph had the prescriptions made up but told Field two days later that he had “chucked the whole damn lot away”. [58] There is no independent corroboration of Field’s story, but it fits the likely time window for infection and its details are perfectly in keeping with Lord Randolph’s character.

Any or none of the foregoing accounts might be true. What matters is that if Lord Randolph had general paralysis, he also had syphilis. In the great majority of cases, syphilis is contracted during sexual intercourse. The first sign of infection is the appearance of a painless ulcer called a chancre that develops at the site where the bacterium passed from the infected to the uninfected person (usually the genitals). The chancre appears between three and ninety days after the initial infection. Its presence marks the primary phase of syphilis, by which time the bacterium has already spread through the blood stream and the lymphatic system.

Between four to ten weeks after initial infection, the infected person enters the secondary phase of syphilis. Common symptoms are malaise, sore throat, headaches, swelling of the lymph nodes and an erratic fever accompanied by a painless, non-itchy rash on the trunk of the body and the hands and feet. The rash may create warty lesions called condylomata lata on areas of moist skin. Like the primary chancre, condylomata lata are highly infectious. Those secondary symptoms typically fade after three to six weeks, even in a patient who is not receiving treatment. The individual now enters a quiescent and relatively uninfectious latent phase. Patients may form the mistaken belief that the disease has gone away. It has not: syphilis remains in the body and can reveal its presence through occasional relapses involving malaise and fever combined with outbreaks of skin lesions and other symptoms. About one-third of people with untreated or poorly-treated syphilis go on to develop additional symptoms at some point after the secondary and latent phases have passed. The onset of those new symptoms marks the tertiary stage. General paralysis is a tertiary condition, now more likely to be referred to as tertiary neurosyphilis or just neurosyphilis. Another form of tertiary neurosyphilis occurs when the disease attacks the spinal cord, causing tabes dorsalis, also known as locomotor ataxia. [59] Impaired walking (gait) is one of the most obvious signs of tabes dorsalis. Given that the meninges that surround the spinal cord are continuous with those that surround the brain, it is not surprising that tabes dorsalis and general paralysis often co-exist in the same patient.

Tertiary syphilis can also affect the heart and blood vessels causing cardiovascular syphilis with circulatory problems and progressive heart failure. There are many other forms of tertiary syphilis whose nature depends on the organ systems affected. Different tertiary conditions frequently occurred in the same patient. The medical complexities of syphilis were described in textbooks like B. P. Thom’s Syphilis (1922), John H. Stokes’s Modern Clinical Syphilology (1928) and Rudolph Kampmeier’s Essentials of Syphilology (1946). [60]

Signs of Syphilis in Lord Randolph Churchill Before the Onset of General Paralysis

If Lord Randolph contracted syphilis in the early to mid 1870s, we would expect him to have shown symptoms of the disease before general paralysis announced its presence in about 1890. In fact, we know that he experienced a number of medical problems in that period. All of the problems mentioned below appear in the medical textbooks of the time as potential signs of syphilis. What is more, they appeared in the order that would be expected in someone progressing through the various stages of syphilis to the development of tertiary disease. I will deal with them in turn.

Sciatica and rheumatism. According to Anne Sebba, Lord Randolph visited society doctor Oscar Clayton in 1878, complaining of sciatica (pains in the lower back and down the legs). Lord Randolph, who concealed much of his ill-health from his wife, told Lady Jennie that Dr Clayton said that he was “below par”. A few months later, Lord Randolph visited Dr Clayton, this time complaining of rheumatism. Lord Randolph told Lady Jennie that Dr Clayton had said that he “was not at all well and that I must look after myself.” [61] One of the indications of syphilitic invasion of the spinal cord is lightning pains affecting the legs and feet. In his textbook of syphilis, B. P. Thom noted that lightning pains can be the first indication of neurosyphilis, adding that “they are not infrequently diagnosed as rheumatism, sciatica or neuritis”. Syphilis could also cause inflammatory changes in joints, affecting the ankles, knees and elbows that could be mistaken for rheumatism or arthritis. Rudolph Kampmeier admitted that, despite being an authority on syphilis, he had sometimes misdiagnosed syphilitic inflammation of the joints as common arthritis. [62]

Inflammation of the mucous membrane. There was a period between March and July 1882 when ill-health prevented Lord Randolph from fulfilling his parliamentary duties. The Times announced that “Lord Randolph Churchill has been seriously ill for some days with inflammation of the mucous membrane.” The announcement quoted Dr Oscar Clayton as saying that “Lord R. Churchill is decidedly improved to-day but he requires absolute quiet and rest.” [63] Lady Jennie nursed her husband in a country house near Wimbledon, away from prying eyes. The couple then travelled to America – Lord Randolph was a firm believer in the therapeutic effects of travel – but he was still unwell when they returned at the end of May and was unable to resume his parliamentary duties until July. Conservative politician Sir William Harcourt told his son of rumours that Lord Randolph’s problem was “internal piles”. Biographer Roy Foster suggested that this episode may have been syphilitic in nature. [64] The skin growths call condylomata lata could develop around the anus in the secondary stage or during latent phase recurrences up to six or seven years after the initial infection. They could be anything from a small mucous patch to “enormous flowery vegetations”, and could take several weeks to clear. [65] Lord Randolph would not have wanted the world to know about such embarrassing and diagnostic symptoms.

Deafness and vertigo. In the mid 1880s, Lord Randolph suffered increasing deafness combined with spells of dizziness (vertigo), an unpleasant condition that returned in the winter of 1892-93. [66] By the 1920s, doctors understood that chronic syphilis can damage the vestibulocochlear nerve that transmits auditory and balance information from the inner ear to the brain. It can also invade the inner ear itself, raising the internal fluid pressure and damaging the organs of hearing and balance. In the pre-antibiotic era, hearing loss and vertigo occurred in around one in twenty adults with syphilis. [67]

Palpitations, fatigue and congestion of the lungs. In August 1885, Lord Randolph reported feeling dull and tired, with “congestion of the lungs”. The following year, the congestion returned. Politician, theatre producer and race-goer Henry Labouchère told Lord Rosebery: “The action of his heart has given way and he takes a lot of digitalis.” In 1890 Lord Randolph was taken seriously ill with heart palpitations for which family physician Robson Roose prescribed belladonna (a sedative), laudanum (a tincture of opium used for pain relief and sedation) and digitalis (used to control heart rate and fibrillation). [68] By the 1920s it had become clear how many patients with long-term syphilis suffered damage to the heart and blood vessels, particularly the blood vessel called the aorta that carries oxygenated blood from the heart to the head and body. The walls of the aorta are prone to become flabby, puckered and stretched as a result of syphilitic infection, sometimes bulging to create an aortic aneurysm. If the valves in the heart that prevent back-flow of blood to the heart are also affected, the efficiency of the heart is further reduced. Between 25 and 50 per cent of patients with general paralysis also had cardiovascular disease. [69] Fatigue, palpitations and shortness of breath caused by a build-up of fluid on the lungs were common manifestations of cardiovascular disease in tertiary syphilis.

We are now a position to put together a cautious timeline taking Lord Randolph from initial infection to death. The timeline runs as follows:

• Early to mid 1870s. Lord Randolph contracted syphilis. In 1874 he saw a specialist in Paris who prescribed medication, presumed to be mercury-based. Lord Randolph threw it away. He visited Dr Oscar Clayton in 1878 and 1879 complaining of sciatica and rheumatism. The “sciatica” could have been the first indication of neurosyphilis: in this case inflammation of the membranes surrounding the spinal cord causing shooting pains in the legs and feet. The “rheumatism” could have been the result of inflammatory changes in the joints.

• March to July 1882. Lord Randolph suffered from “inflammation of the mucous membrane” that prevented him from fulfilling his parliamentary duties. What were rumoured to be “internal piles” could have been the growths known as condylomata lata that can develop during a latent phase outbreak.

• Mid 1880s and 1892-93 onwards. Lord Randolph experienced deafness and vertigo, possibly caused by syphilitic damage to the vestibulocochlear nerve or to the inner ear itself.

• August 1885. Lord Randolph complained of tiredness and “congestion of the lungs”, a possible sign of developing cardiovascular syphilis.

• 1890. Lord Randolph experienced heart palpitations for the first time. Palpitations are recognised consequences of cardiovascular syphilis. They remained with him through to his death. At least one acquaintance thought that the extreme optimism he showed when heading off to South Africa in search of gold was an early mental symptom.

• 1893-95. We are on firmer ground when noting the poor articulation and slurring of speech that were reported in 1893. A tremulous tongue and lips were also observed. In March 1894, Julian Osgood Field was shocked by the change in Lord Randolph’s gait. By October his walking had become staggering and uncertain. By the middle of 1894 his speech was described as painful to listen to. Lord Randolph acknowledged in 1893 that he had experienced episodes of numbness. More severe attacks occurred in 1894, affecting both his feet and his hands. He also lost power in his limbs, starting with his left hand. His handwriting became shaky and error-prone. Sudden outbursts of uncontrollable anger began. Soon Lord Randolph was showing frequent and rapid mood swings, becoming agitated and sometimes violent up to twenty times a day. . Delusions began in mid 1894. By January 1895, Lord Randolph was having one delusion after another, some of them grandiose. Lord Randolph consistently denied that his symptoms were real, sometimes insisting that he was perfectly well and sometimes seeking alternative excuses for his problems. That denial may itself have been a symptom of his disease. A general “loss of mental power” (incipient dementia) was noted in October 1894. By January his condition was one of mental feebleness. Winston Churchill said that his father was childlike in mind as well as body.

From the onset of Lord Randolph’s syphilis in the 1870s to his death in 1895 took around 20 years. General paralysis only took hold in the last few years but was unmistakable to experienced doctors.

Disputing General Paralysis: the Search for Alternative Explanations

Despite the evidence, and the unanimity of contemporary neurologists, some modern Churchillian scholars have been reluctant to accept that the father of Sir Winston Churchill contracted a sexually-transmitted disease that eventually killed him. Modern attempts to provide alternative explanations for Lord Randolph’s ill-health began with an article by Dr John H. Mather that appeared in edition 93 (1997/97) of Finest Hour, published by the International Churchill Society. Mather rejected claims that Lord Randolph died of general paralysis. He also rejected what he saw as the corollary assumption that the doctors who treated Lord Randolph believed him to be syphilitic. [70] Mather’s arguments have been cited with approval by Addison (2005), Celia and John Lee (2010), Langworth (2017) and others. In correspondence with Richard Langworth, Sir Robert Rhodes James apparently dismissed the idea that Lord Randolph has syphilis as a “canard” (i.e., a rumour or falsehood). Celia and John Lee called it a “smear”. Mather concluded: “It is no longer possible to say that [Lord Randolph] died of syphilis.” [71] Mather knew of the involvement in Lord Randolph’s case of Robson Roose, Thomas Buzzard and William Gowers through the publication of their correspondence and documents but did not reference The Times obituary or any of the articles that appeared in the Lancet and the British Medical Journal around the time of Lord Randolph’s death. Like most historians, Mather showed no sign of having been unaware of those publications.

Mather put forward a number interrelated arguments for why Lord Randolph did not have syphilis or general paralysis. Those arguments will be considered now.

1. The risk of contracting syphilis from a single encounter. Journalist Frank Harris and biographer Anne Sebba both suggested that Lord Randolph contracted syphilis through single episodes involving infected women, albeit in different times and places. [72] Mather argued that such accounts were highly unlikely because “the chance of contracting syphilis in one sexual encounter is less than one percent”. Mather did not provide a reference in support of that figure and observed elsewhere in his article that “the initial and secondary manifestations of syphilis are highly contagious.” [73]

The truth is that the chance of contracting syphilis from a single sexual encounter depends entirely on whether or not the partner has infectious skin lesions at the time of the encounter. A recent review estimated the risk of contracting syphilis at close to zero if the sexual partner is in the tertiary phase or an asymptomatic latent phase without skin lesions. In contrast, the risk rises to between ten and thirty per cent if the partner is in the primary or secondary stages of the disease, or is suffering a latent phase relapse with skin lesions. [74] Even if Lord Randolph had just a single encounter with someone with infectious skin lesions, the risk to him was substantial.

2. No evidence of transmission within the family. Mather argued that if Lord Randolph had syphilis, he would have transmitted it to Lady Jennie and through her to his sons Winston and John, yet there is no evidence of that having happened. [75] But Lady Jennie would only have been at risk of contracting syphilis if Lord Randolph was in the short-lived primary and secondary stages of syphilis, or was having a latent phase relapse. If she managed to avoided infection, then she could not have passed the disease on to her sons during pregnancy or childbirth (as can happen in congenital syphilis, sometimes misleadingly termed hereditary syphilis). According to Anna Sebba, Lord Randolph contracted syphilis from a chambermaid at Blenheim Palace soon after his marriage. Winston Churchill was born seven and a half months after his parents’ marriage, so Lady Jennie would most likely have been pregnant at the time. Also, if Lord Randolph consulted a doctor during an active phase (e.g., Dr Clayton in London or the unnamed specialist in Paris), he would have been told in no uncertain terms to refrain from sex until his symptoms had fully abated. In addition, he would not have wanted to expose a revealing rash to his wife.

Anita Leslie, author of the first biography of Lady Jennie, was the granddaughter of Lady Jennie’s sister Leonie and privy to family gossip and rumours. Leslie claimed that sexual relations between Lord Randolph and Lady Jennie ended in 1881. It is worth noting that diminishing sexual power is one of the first indications of syphilitic invasion of the spinal cord which can lead to total impotence. Loss of sexual potency would have hit Lord Randolph hard. At first, he would probably have avoided sexual relations rather than admit his problems to his wife, but Leslie claimed that he eventually summoned up the courage to confess his syphilis to Lady Jennie in 1886. [76] The fact that Lord Randolph’s wife and children avoided syphilis does not mean that he was not infected.

3. Over-diagnosis of syphilis as a cause of neurological illness. Mather argued that many Victorian doctors, including neurologist Thomas Buzzard, over-diagnosed syphilis as a cause of neurological illness. Mather wrote of Buzzard that “It was his opinion that 95 percent of his patients had the disease [syphilis]”, citing as evidence page 11 of Buzzard’s book Clinical Aspects of Syphilitic Nervous Affections (1874). Mather’s claim was subsequently echoed by Celia and John Lee. [77]

On page 11 of his book, Thomas Buzzard discussed paralyses occurring in men between the ages of twenty and forty-five. He said that where a paralysis could not be attributed to physical injury, a form of kidney disease called Bright’s disease, or a stroke secondary to heart disease, then in his experience there was a 95 per cent chance that the patient had syphilis. Buzzard was talking here about a very specific group of men with paralyses, men in whom other common causes had been excluded. He was not talking about general paralysis in which the paralysis takes the form of progressive weakness accompanied by loss of sensation (numbness). [78] Elsewhere in the book, Buzzard discussed neurological symptoms occurring in syphilitic patients as a result of narrowing of arteries, inflammation of the meninges and aggregations of dead tissue called gummas that can exert pressure on the nervous system. But like other authorities, Buzzard drew a clear line between syphilitic disorders and general paralysis, which he did not regard as syphilitic. In fact, Buzzard argued that a diagnosis of general paralysis should only be considered when other causes, including a history of syphilis, had been eliminated. Far from over-diagnosing syphilis in cases of general paralysis, Thomas Buzzard would only diagnose general paralysis when syphilis had, to his mind, been excluded. In 1874 that meant quizzing patients and their families, and looking for scars left by primary chancres. Neither method was reliable. [79]

Turning from Buzzard to the “well-respected neurologist” William Gowers, Mather argued that Gowers “emphasized this overdiagnosis of neurologic syphilis” in a series of lectures on Syphilis and the Nervous System he gave in 1899 (the same lectures in which Gowers estimated the prevalence of syphilis in men at seven to ten per cent). [80] Mather knew that Gowers was a colleague of Thomas Buzzard but it is not clear he knew that Gowers was consulted by Buzzard and Roose and agreed with them that Lord Randolph had general paralysis (as noted in The Times obituary). I have read Gowers’s lectures carefully and have been unable to find any statement to the effect that the neurological effects of syphilis were systematically over-diagnosed. Gowers did note complaints from some doctors that psychiatrists in general placed too much emphasis on diagnosis, but he rejected those complaints, maintaining that classifying mental disease was an important step towards understanding it. [81] Gowers did not accept that general paralysis was a syphilitic disease. [82]

On a related point, Celia and John Lee (2010) questioned whether, when Thomas Buzzard wrote about general paralysis, he was actually referring to the disease whose full name was general paralysis of the insane. The Lees argued, for example, that when Dr Buzzard wrote to Sir Richard Quain on New Year’s Eve 1894, he “only referred to Lord Randolph’s condition as general paralysis, leaving open the interpretation.” [83] As should be clear by now, the term “general paralysis” was used routinely in place of the more cumbersome “general paralysis of the insane”. The Times obituary andthe Lancet articles talked simply of general paralysis. The review that appeared in the British Medical Journal a week after Lord Randolph’s death was entitled “General Paralysis”. Buzzard’s use of the term “general paralysis” was entirely in keeping with general medical usage at the time. There was absolutely no ambiguity.

4. Roose on the cause of general paralysis. Mather argued that Robson Roose was inconsistent in his statements about the cause of general paralysis, blaming it sometimes on syphilis and sometimes on exhaustion. Roose was a generalist, not a specialist, but in 1875 he published a 25-page booklet entitled Remarks Upon Some Diseases of the Nervous System. Roose was in his mid twenties at the time and just starting out on his medical career. The booklet contains sections on hydrocephalus, delerium tremens, inflammation of the brain, apoplexy (stroke), chorea, epilepsy and hysteria. Interestingly, it is dedicated to “my friend, Oscar Clayton, Esq., As a tribute of esteem and admiration for his great professional skill.” Clayton was the doctor Lord Randolph visited in 1878 and 1879 complaining of sciatica and rheumatism. He was also the doctor quoted by The Times in 1882 in relation to Lord Randolph’s “inflammation of the mucous membrane”.

In the section on inflammation of the brain, Roose observed that chronic inflammation can affect the membranes surrounding the brain or the cerebral substance itself. According to Roose, “Chronic inflammation of the brain attacks persons of exhausted habits, brought on by excesses and irregular living … The only treatment is to try and combat the various morbid symptoms as they arise and improve the general health in every way; but, in two or three years, general paralysis is almost sure to occur.” That is the section quoted by Mather who commented: “Here the term ‘general paralysis’ is clearly associated with exhaustion – not syphilis.” [84] As should be clear by now, Roose was simply echoing the dominant view among specialists that general paralysis was caused by exhaustion brought on by excess and irregular living. Roose noted that chronic hydrocephalus – a very different disease – could occur in the children of syphilitic parents (i.e., congenital syphilis [85]), but at no point did he mention syphilis in relation to other diseases of the nervous system. Roose never blamed general paralysis (or chronic inflammation of the brain) on syphilis, nor can he be said to have over-diagnosed syphilis in his patients.

5. Lord Randolph’s treatment. Mather argued that “If Dr Buzzard had been convinced that Lord Randolph had advanced syphilis, he would have treated him with mercury and with potassium iodide … [but] Buzzard makes no mention of such treatments.” [86] That claim was endorsed by the Lees (2010) and by Langworth (2017). We have seen, however, that the fact that general paralysis did not respond to mercury was widely employed as an argument against syphilis being a cause of general paralysis. At the risk of becoming repetitious, Thomas Buzzard did not believe that general paralysis was caused by syphilis; neither did the eminent colleagues he consulted. Hence there was no point treating Lord Randolph’s general paralysis with mercury or potassium iodide. [87]

6. Missing symptoms. Mather noted that some of the symptoms of general paralysis were missing in Lord Randolph until shortly before his death in 1895. The variability of general paralysis is something that every authority commented on. For example, Lord Randolph seems never to have shown the asymmetric, unresponsive pupils that were a regular feature of general paralysis. But about a third of general paralysis patients did not show pupillary abnormalities. Lord Randolph was by no means unique in that regard. [88]

When Lord Randolph was on his world tour in 1894, he sent many letters back to England. Mather claimed that signs of dementia, a universal feature of late-stage general paralysis, were “absent from Randolph’s writings until the end of 1894”. Mather added that Lord Randolph “wrote more lengthily, and his script became shaky, but it was never unintelligible. Until the last, when he was in a coma, his thoughts expressed in writing were rational; they include a cogent letter to Winston while on the world tour in August 1894.” [89] The letter Mather cited was sent from Monterey on 21 August 1894. [90] In it, Lord Randolph strongly opposed the choice of army regiment that Winston had recently expressed, said how pleasant California was, and outlined his plans for onward travel to Japan and beyond. Mather could also have cited letters from Lord Randolph held in the Churchill Archives, including his last letter to his mother dated 22 November 1894 in which he expressed his views on Home Rule for Ireland whilst assuring the Duchess that he was “relieved of his troubles” for ever.

Those letters are indeed coherent, if somewhat rambling. Lord Randolph also repeated himself constantly across letters written to the same recipients within days of each other. There are indications of memory loss in the letters even if Lord Randolph’s intelligence and character remain visible. [91] At the end of October 1894, George Keith alerted Robson Roose to indications of a loss of mental power, including a tendency to use the wrong words. By 1 January, Lord Randolph was as helpless in mind as a little child.

Invasion of the brain areas responsible for thinking and memory seems only to have occurred to a significant degree in November or December 1894. But Lord Randolph displayed a fluttering tongue, poor articulation, mood swings and other symptoms of general paralysis two or three years earlier. Variability in the onset of dementia, like variability in the onset of other symptoms, was a well-known feature of general paralysis. [92]

7. Alternative explanations for Lord Randolph’s symptoms. In some ways, I have saved Mather’s most important argument for last. Mather argued that Lord Randolph’s multiple symptoms could be explained by a variety of other factors including exhaustion, high blood pressure, arterial spasms induced by heavy smoking, a long-term speech impediment and hearing difficulties, and a left-sided brain tumour which induced ‘psychic seizures’ induced by epilepsy. Mather regarded such a combination of factors as “a less titillating but far more logical diagnosis” than syphilis. [93] Syphilis was notorious for mimicking the effects of other diseases, so it would not be surprising if some of the symptoms shown by Lord Randolph could occur in other conditions. That said, some of the specific alternatives offered by Mather and others are problematic.

a) Optimism and rage. Regarding Lord Randolph’s over-optimism, impatience and short temper during his last five years, Mather argued that “Much of [Lord Randolph’s] behaviour … seems to be no more than an accentuation of his prior personality.” [94] It is true that Lord Randolph was always impulsive and short-tempered, but his outbursts in the House of Commons and the hairdresser in 1894 shocked people who knew him well. By the time he was into his world tour, Lord Randolph was out of control, flying into rages for little or no reason. Loss of the ability to control (inhibit) one’s own behaviour is associated with damage to frontal regions in the brain. [95] I would argue increasing signs of inability to control his own behaviour reflected reduced functioning of frontal regions caused by syphilitic inflammation of the meninges surrounding Lord Randolph’s brain and the invasion of his prefrontal cortex by Treponema pallidum.

b) Deafness. Continuing in the same vein, Mather proposed that the hearing problems Lord Randolph complained of in the mid 1880s were just an accentuation of hearing problems he had experienced as a youngster. [96] But the increasing deafness of Lord Randolph’s mid thirties was accompanied by distressing vertigo. There is no suggestion that Lord Randolph experienced vertigo as a youngster. As noted above, hearing loss and vertigo are both well-known symptoms of syphilitic damage to the auditory system.

c) Brain tumor. Turning to Lord Randolph’s speech problems, Mather said that he “always had a slight speech impediment … so it is difficult to single out problems with his speech.” [97] Anita Leslie said that before his illness, Lord Randolph “had a curious guttural pronunciation, almost a lisp, which increased when he was nervous.” [98] His colleagues in parliament and elsewhere were familiar with his way of talking but were shocked and dismayed by the slurred speech and poor articulation of Lord Randolph’s parliamentary speech of February 1893. William Scawen Blunt found his friend’s speech painful to listen to. By late October 1894, Lord Randolph’s speech was even thicker and he was showing a tendency to use the wrong words.

Mather suggested that the deterioration in Lord Randolph’s speech might have reflected a developing tumor deep in the left side of his brain, commenting that the “progressive march of the disease process strongly suggests an expanding lesion or mass.” [99] The effects of general paralysis were undoubtedly confused with brain tumors from time to time. American syphilologist John Stokes warned that “opportunities for the confusion of brain tumor with cerebral syphilis are numerous”. In a line that indicates just how much the medical landscape has changed, Stokes added: “fortunately brain tumor is much less common in ordinary practice.” [100]

d) Epilepsy. There are problems with the tumor theory, however. Many of Lord Randolph’s symptoms fluctuated from day to day, especially in the early stages of his final illness. A neurologist consulted by Anne Sebba observed that the symptoms caused by brain tumors are much more constant and argued that the “intermittent nature of some of [Lord Randolph’s] symptoms coming and going would be much against a brain tumour.” [101] That argument might potentially be countered by another of Mather’s proposals, which was that a deep-seated tumor could have triggered periodic epileptic activity in Lord Randolph’s brain. For example, Mather propose that electrical discharges resulting from a brain tumor could have generated “fugue states” or “psychic seizures” during which Lord Randolph was unable to call words to mind. Langworth argued that Lord Randolph’s speech problem was strongly suggestive of epilepsy. [102]

In most people, language is controlled by the left side (hemisphere) of the brain and can be affected by left-sided brain damage of many different sorts. The inability to remember words and sometimes using the wrong word are typical of a form of language disorder (aphasia) that is known as anomia. Anomia can definitely be caused by left-sided brain tumors: I have studied such patients in the course of my own research. [103] But word-finding difficulties are also found in patients with progressive dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease and the less common frontotemporal dementia. In those patients, the naming problems are associated with loss of brain cells in the temporal lobes of the brain, particularly on the left and towards the front. Patients in the early stages of general paralysis show word-finding problems very similar to those seen in Alzheimer’s disease, probably because of loss of brain cells in the same areas. [104]

Fluent speech requires the exquisite co-ordination of many muscle groups, including the ones that control breathing, the vocal cords, the tongue and the lips. Those muscle groups must be recruited at the right moment and with the right timing. Speech begins as motor programs created in specialised motor areas between the frontal and parietal lobes of the left hemisphere. It then recruits multiple brain regions, including the cerebellum and the basal ganglia, structures at the base of the brain that are important for co-ordinating voluntary movements and ensuring the precise timing of movements. Slurred speech and poor articulation represent a form of language disorder known as dysarthria. Dysarthria can be caused by damage to speech motor areas, the cerebellum, the basal ganglia and pathways that communicate between brain areas and transmit instructions to the muscles. The precise form of the dysarthria varies according to the site of the damage. We have only brief accounts of Lord Randolph’s speech after the onset of his illness but it seems to have been characterised by slurring and poor articulation of sounds. One possible explanation would be that his speech was impaired as a result of invasion of his cerebellum and basal ganglia by Treponema pallidum. [105]

As regards epilepsy, the condition was virtually untreatable in the 19th century but was studied intensively by neurologists and psychiatrists because of its frequency and impact on peoples’ lives. John Russell Reynolds, one of the doctors who agreed upon the diagnosis of general paralysis for Lord Randolph, was an expert on epilepsy. He published a book in 1861 called Epilepsy: Its Symptoms, Treatment, and Relation to Other Chronic Convulsive Diseases and wrote the chapter on epilepsy in the System of Medicine he edited in 1866. Thomas Buzzard knew as much about epilepsy as he did about general paralysis. Buzzard was personally responsible for founding the National Society for Epilepsy in 1892, three years before Lord Randolph’s death. Reynolds and Buzzard would have had no hesitation in diagnosing epilepsy if they thought it was responsible for any of Lord Randolph’s symptoms. They did not.

e) Arterial spasms. Mather suggested that the episodes of numbness that Lord Randolph experienced in August and October 1894, affecting his hands and feet, could have been caused by arterial spasms (vasospasms) provoked by his chain-smoking. [106] Vasospasms occur when muscles in the walls of arteries constrict, causing the arteries to narrow with a resulting reduction in blood flow. Vasospasms in the hands and feet cause the fingers and toes to go blue. When the blood flow returns to normal, the affected areas may turn red and throb, or go numb. This is known as Reynaud’s phenomenon. Such vasospasms can be relieved by warming and massaging the hands and feet, which may be why that treatment was attempted with Lord Randolph. But the symptoms of vasospasm affecting the hands and feet are not a close match to the numbness reported for Lord Randolph. The most common symptoms of vasospasm are migraines and chest pains caused by constriction of the coronary artery. As far as I am aware, Lord Randolph did not suffer migraines and his cardiovascular problems were those of insufficiency (breathlessness and fluid on the lungs) rather than vasospasm. In contrast, loss of the sense of touch, vibration, pain and position sense in the limbs are seen in up to 60 per cent of patients with neurosyphilis as a result of degeneration of nerve fibres in parts of the spinal cord. [107]

The alternative accounts of Lord Randolph’s illness are forced to posit multiple, unconnected causes for Lord Randolph’s various symptoms. As we have seen, some of the specific hypotheses are problematic. Even if we were to accept them all, other symptoms Lord Randolph displayed remain unaccounted for. They include delusions that are associated in other forms of dementia with degeneration affecting the frontal regions of the brain. [108] They also include the fluttering tongue and lips, and the gait disorder which are classic signs of tertiary neurosyphilis. Each and every one of Lord Randolph’s symptoms can be given a logical explanation in terms of syphilitic infection leading to general paralysis, tabes dorsalis and cardiovascular syphilis.

Andrew Norman, himself a medical man like John Mather, is one of the few historians to have engaged with Mather’s arguments in any detail. Norman’s book Winston Churchill: Portrait of an Unquiet Mind (2012) also contains the only reference I have found to The Times obituary. (The fact that Winston Churchill never cited that obituary or the Lancet articles may be one reason why they have not been picked up and used by more recent writers.) Norman could see no reason why one would invoke multiple causes for Lord Randolph’s assorted symptoms when one was capable of explaining them all. [109] I agree.

Winston Churchill on his Father’s Illness

In October 1894, when Winston Churchill was nineteen years old and his parents were on their world tour, the reports coming back from Dr Keith about Lord Randolph’s condition were causing increasing concern. Winston visited Robson Roose, familiar to him as the family physician, and persuaded Roose to tell him exactly how his father was. Roose showed Winston his father’s medical reports. Winston then wrote to his mother saying that he had “never realised how ill Papa had been and never until now believed that there was anything serious the matter.” [110] A week later, Winston wrote to Lady Jennie following another update from Dr Roose (probably based on the letter written by Dr Keith on 3 October mentioning Lord Randolph’s numbness and loss of power in his left hand; also his mood swings and the near assault on one of his valets).

It is inconceivable that Robson Roose could have talked Winston through the full medical reports without mentioning general paralysis, particularly at a time when that diagnosis carried few if any negative connotations. Winston could be forgiven for not reading the obituary that appeared in The Times the day after his father’s death, but The Times was the newspaper of record for all things concerning politics and the establishment. He must surely have read the obituary at some point, if only when preparing the biography of his father that he published in 1906. The term “general paralysis” appears in the second paragraph of the obituary and again in the section at the end that was contributed by the Lancet.

Winston addressed his father’s last illness in the biography, saying that in the winter of 1892, “a dark hand intervened … symptoms of vertigo, palpitations, and numbness of the hands made themselves felt, and his condition was already a cause of the deepest anxiety to his friends.” Winston added that when his father spoke in parliament in 1893, he spoke “with a voice whose tremulous tones already betrayed the fatal difficulty of articulation.” Commenting on his father’s lack of insight into his decline, Winston said: “By a queer contradiction it is ordained that an all-embracing optimism should be one of the symptoms of this fell disease. The victim becomes continually less able to realise his condition. In the midst of failure he is cheered by an artificial consciousness of victory.” [111]

The reason Winston gave in 1906 for his father’s illness was that “The great strain to which he had subjected himself … the vexations and disappointments of later years and finally the severe physical exertions and exposure of South Africa had produced in a neurotic temperament and delicate constitution a very rare and ghastly disease.” Winston did not identify general paralysis by name, alluding only to “the numbing fingers of paralysis laid that weary brain to rest.” [112] Apart from the fact that general paralysis was not very rare in the 1890s, the explanation Winston gave for his father’s illness in terms of strain, vexations, disappointment, etc. was very much the explanation offered by the Lancet and the British Medical Journal. It was the explanation that could be found in all the medical textbooks of the time and the explanation Robson Roose would have given Winston when he asked to be appraised of his father’s situation. That would all change when medical research established beyond doubt that general paralysis was caused by syphilis.

By the 1920s, Winston Churchill would have known that if Buzzard, Gowers and Reynolds were correct in their diagnosis, then Lord Randolph’s death was due to chronic syphilitic infection. When Winston was in his seventies, he told his private secretary that his father died of locomotor ataxia (tabes dorsalis), calling it “the child of syphilis”. [113] Winston chose to focus on the spinal cord symptoms like Lord Randolph’s gait disturbance, numbness and hearing loss rather than the mood swings, delusions and dementia that were also part of his father’s illness. We will never know if Winston would have been swayed by recent, alternative accounts of his father’s complicated medical history. Winston was a realist who understood human flaws and weaknesses. He developed a close relationship with his mother after his father’s death and would have been fully aware of Lord Randolph’s complex, flawed character. In recent times, historians like Martin Gilbert and Andrew Roberts have had no qualms about concluding that syphilis killed Lord Randolph. [114] And despite being an Old Etonian, Oxford graduate and former member of the Bullingdon Club like Lord Randolph, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson did not hesitate to state that Lord Randolph died “in political isolation and syphilitic despair”. [115]

The reluctance of some historians to accept that Lord Randolph died from syphilis and general paralysis puts me in mind of the refusal by members of the Richard III Society to accept that their hero suffered from curvature of the spine. Only when King Richard’s skeleton was discovered in 2012 did they reluctantly acknowledge that he had indeed suffered from the condition they had previously dismissed as a slur and a calumny. I believe the time has come to accept that Lord Randolph was one of the many young men of his type who contracted syphilis and that his susceptibility was compounded by his refusal to take treatments that might have prevented the infection from progressing. But he did refuse, with the result that his syphilis progressed from primary to secondary through latent to tertiary neurosyphilis and cardiovascular syphilis. Thomas Buzzard, William Gowers and Sir John Russell Reynolds knew what they were talking about when they diagnosed general paralysis as the main cause of Lord Randolph’s final illness. Knowing what we do now, we can plausibly identify several of Lord Randolph’s earlier medical problems as caused by syphilis. Lord Randolph Churchill was all too human and died of an all too human disease. Saying that does not in any way detract from his many achievements as a politician or reflect in any way on other members of his family.

Acknowledgements