Churchill Society News

Jane Williams 1929–2023

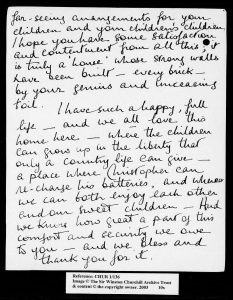

Celia Sandys & Lady Williams at the 34th International Churchill Conference

July 16, 2023

“Let Us Be Contented”

By David Freeman

Jane Williams (Lady Williams of Elvel, to provide her formal title) died peacefully at her London home on July 15. She was a longtime friend of the International Churchill Society (ICS) and the society’s senior honorary member. Her death marks a final break of sorts: she was among the most prominent of the last surviving members of Sir Winston Churchill’s personal staff. This, however, was only one of many remarkable facts about her in a long and incredible life that extended just far enough to enable her to watch her son Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, crown King Charles III in Westminster Abbey this past May.

Jane Portal was born in 1929, the daughter of Iris Butler, a journalist and historian, whose brother R. A. “Rab” Butler was a leading Conservative politician of the mid-twentieth century and who served in Churchill’s wartime and postwar governments. The father of Iris and Rab, Sir Montagu Butler, served as Governor of the Central Provinces of India and was the grandson of a Head Master of Harrow, Churchill’s old school. Jane’s father, Gervase Portal, who could trace his heritage back to King Charles II, was a half-brother of Sir Charles Portal, who served as Chief of the Air Staff during the Second World War. Thus, two of Jane’s uncles worked at close quarters with Churchill at the highest level.

It was “Uncle Rab” who told his niece in December 1949 that Churchill was looking to hire a new secretary and suggested that she apply. In conversation with Churchill’s granddaughter Celia Sandys, Jane told the 2017 Churchill Conference in Washington, D.C. about her job interview with the former Prime Minister, who was then Leader of the Opposition. Arriving at the Churchills’ London home of 28 Hyde Park Gate, she saw Churchill dressed in Parliamentary attire at the head of a hallway: “He walked down the passage towards me…put out his hand, shook my hand, walked very slowly all the way round me, smiled at me, and walked away. Joe Sturdee, who was the head secretary,…said to me, ‘Good, that’s all right. Can you begin on Monday?’” Jane did and continued to work for Churchill until his retirement in April 1955. The complete video of the conversation, which was the highlight of the conference, can be viewed here.

2025 International Churchill Conference

I must now beg your indulgence; I cannot write a eulogy for a friend without injecting myself. The 2017 conference marked the beginning of a wonderful friendship between Jane and me, but this almost did not happen.

The Churchill Society flew Jane first-class on American Airlines from London’s Heathrow to New York’s John F. Kennedy (JFK) International Airport. She travelled alone, so we arranged with Randall Baker, one of our stalwart local members whom we also lost this year, to pick her up from the airport. Randall had not met Jane before, so he dutifully stood inside the arrival hall holding up a sign that read “Jane Williams.” An elderly woman who appeared to fit the description approached him with her luggage. He took her to his car, but as they began making the drive into town, their conversation revealed that Randall had collected the wrong Jane Williams. Fortunately, the mix-up was quickly corrected, although for a moment there was panic in the ranks of the ICS leadership that we had lost the eighty-seven-year-old mother of the Archbishop of Canterbury and left her stranded at the airport.

To avoid a recurrence of such a problem on her departure after the conference, it was decided that we would hire a limousine service to take Jane to JFK and send one of our team leaders along to make sure everything went as it should. Her flight for London was scheduled early in the morning, which meant leaving the hotel in mid-town Manhattan at 5 am. Since my own flight home was not due to leave until much later in the morning, I volunteered to accompany Jane to the airport.

At five o’clock in the morning, Jane duly appeared looking fresh and proper in the lobby of Marriott’s Essex House on Central Park South. Our driver was waiting, and we were soon on our way to the airport. By way of conversation, I mentioned that I had attended the Metropolitan Opera the night before. In this way we discovered that we were both great opera aficionados. She said that she and her husband Charles were both dedicated Wagnerians, which struck me as ironic, but I kept that to myself.

At JFK we arrived at the American Airlines terminal, and I used my credit card to rent a cart to take her luggage inside, while the driver waited for me. At the counter, I told the agent Jane’s name, but, after some time studying her monitor, the agent told me that there was no passenger listed on the flight to Heathrow by that name. After further study it emerged that, although Jane had flown in on American, she was returning to London on British Airways, which codeshares with AA. That was all right then, but unfortunately BA operated from a different terminal, on the other side of the airport.

I bundled Jane and her luggage back into our waiting car, and the driver successfully navigated the complex of roadways that took us to the correct terminal. Once again, I used my credit card to rent a cart, and once again I took Jane straight to the counter, on the wall behind which was a large sign proclaiming “British Airways.” I informed the agent of Jane’s identity, only to be told, “Oh, this isn’t British Airways. This is Air Jamaica.” I looked once more at the sign on the wall to make certain I was not a complete fool. The agent then explained that BA had recently moved to a different counter, which—fortunately—was still in the same terminal.

Trying to remain calm, I escorted Jane to what I prayed would be the correct counter for once. A temporary banner identified the location to which I had been directed, and I approached the agent behind it, saying, “Please God, tell me this is really British Airways.” The agent confirmed that it was, and that Jane was a passenger on the next flight to London. I requested that they have someone escort Jane through security and down to the gate and ended by leaning over the counter and telling the agent, “This is the mother of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and, if we lose her, we are all going to hell.”

Fortunately, all went well after that fiasco. Jane had thoughtfully invited me to visit her the next time I was in London. Consequently, when I made plans to go to London the following June, I looked at the schedule of the Royal Opera House to discover what performances would be taking place during my visit. When I learned that Lohengrin was on the schedule, I recalled Jane’s stated passion for Wagner and decided that I would invite her to attend a performance with me. She immediately responded to say “yes,” and that “yes” cost me a lot of money.

I knew that I could not buy cheap seats, nor could I expect an elderly woman to navigate the steep steps of the amphitheatre at the Royal Opera House. I broke the bank and bought two tickets for seats in the middle of the stalls: prime viewing at a prime price. But it was worth every penny. How often would I get to take one of Winston Churchill’s secretaries to the opera? I thought I would also have to hire a taxi to collect her, but she insisted on travelling by herself on the Underground. She lived near a stop on the Piccadilly Line that could easily whisk her to Covent Garden. I half expected that she might wish to leave the performance early, given her age and the (typically Wagnerian) length of Lohengrin. Not a bit! She stayed to enjoy every minute.

We began a regular correspondence after that, which mostly focused on our mutual love of opera. I would send her lengthy emails every few months describing in detail each opera I had attended recently and my impressions of the performance. Although she read her email, she always responded with beautifully handwritten letters, noting one time that “Whilst I love the ‘IT,’ social media, etc. I am quite unable to reply in the same method. It is too late now (at 90 years!)” This was all to the good, so far as I was concerned, because I saved and cherished every letter.

Sometimes Jane would telephone me. There is an eight-hour time difference between London and Los Angeles, where I live. No matter, whenever I saw that an incoming call was from her, I would drop anything else I might be doing and answer immediately. There was no such thing in my world as an inconvenient time for her to call.

I took enormous pains with my “opera reports” to Jane, drafting, revising, and carefully proofreading each one before I finally hit “Send.” Always at the front of my mind was the fact that this was a woman who regularly took dictation from Winston Churchill for five and a half years. “That’s all I have to compete with,” I would think. She kindly replied that she enjoyed these reports so much that she would print them out and make notes on them with her own thoughts about the operas and the singers.

More than once, Jane would answer questions for me about Churchill’s habits as I worked at putting together an issue of Finest Hour. Could there be a more authoritative source? She once added a postscript to a letter that read, “When drafting letters for WSC he would not let us use ‘delicious’ or ‘grateful’ but he liked ‘warmest’!!” Thereafter I always ended my own letters to her with the word “warmest.”

Jane and I had planned a pair of return visits to the Royal Opera House in the summer of 2020 and were both “warmly” looking forward to this, but the Covid epidemic cancelled those plans, as it did so many other things in the world. She wrote in early 2021 to say that she had received her vaccination and experienced no side effects. Fortunately, we were able to meet one last time at that year’s Churchill Conference, which took place in London in early October, when the world was just beginning to re-emerge from lockdown.

I collected Jane from her home in a taxi and took her to the RAF Club, where ICS was having a reception. Inevitably we spoke about opera. Unfortunately, she was not able to remain for long at the reception, because by then it had become too disorienting for her to be among large groups of people. I was supposed to take her home as well and started to panic when I feared that I had lost her. “Not again!” I thought. Fortunately, I discovered the magnificent Paul Boateng (Lord Boateng), who told me that he had personally seen Jane to a taxi to take her home.

In one of her letters, Jane enclosed a sheet of paper with a few lines from the end of Churchill’s first essay in Thoughts and Adventures, printed in the “psalm” style in which he liked to have his speech notes arranged. “I thought,” she wrote, “you might like to read this ‘piece’ by Sir Winston. (I read it nearly every day.)”

Let us be contented with what has happened to us

and thankful for all we have been spared.

Let us accept the natural order in which we move.

Let us reconcile ourselves to the mysterious rhythm of our destinies,

such as they must be in this world of space and time.

Let us treasure our joys but not bewail our sorrows.

The glory of light cannot exist without its shadows.

Life is a whole, and good and ill must be accepted together.

The journey has been enjoyable and well worth making—once.

David Freeman is editor of Finest Hour.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.