Finest Hour 188

“To Have Worked with Him”

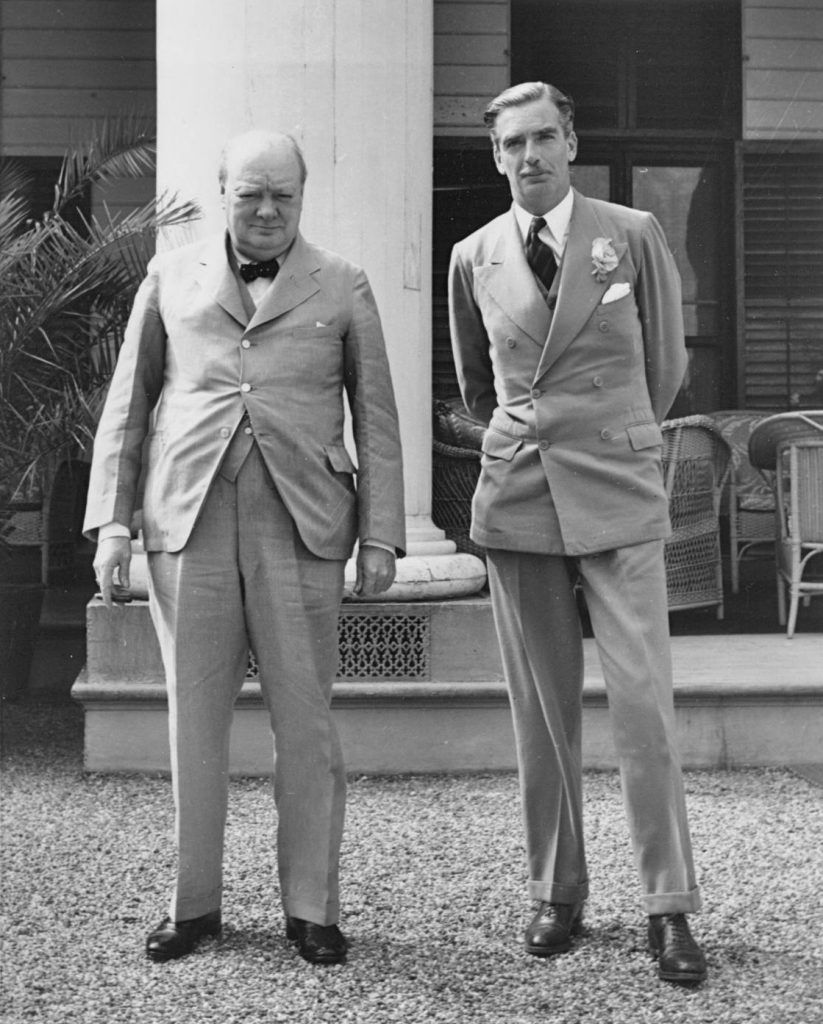

Churchill and Eden, 1943

August 5, 2020

Finest Hour 188, Second Quarter 2020

Page 33

By Iain Carter

Iain Carter is Director of the Conservative Research Department. He has previously been Political Director of the Conservative Party and a special adviser to the Leader of the House of Lords.

Winston Churchill said, “Politics is not a game. It is an earnest business.”1 There are few who have experienced the gravity of politics quite so acutely as he did, and during his own time in 10 Downing Street Churchill served alongside five men who went on to follow him as Prime Minister. Three of them, Attlee, Eden, and Macmillan, worked much more closely with him than did Alec Douglas-Home and Edward Heath. Yet the relationship all five of them had with Churchill played a part in their individual ascents to the pinnacle of British politics.

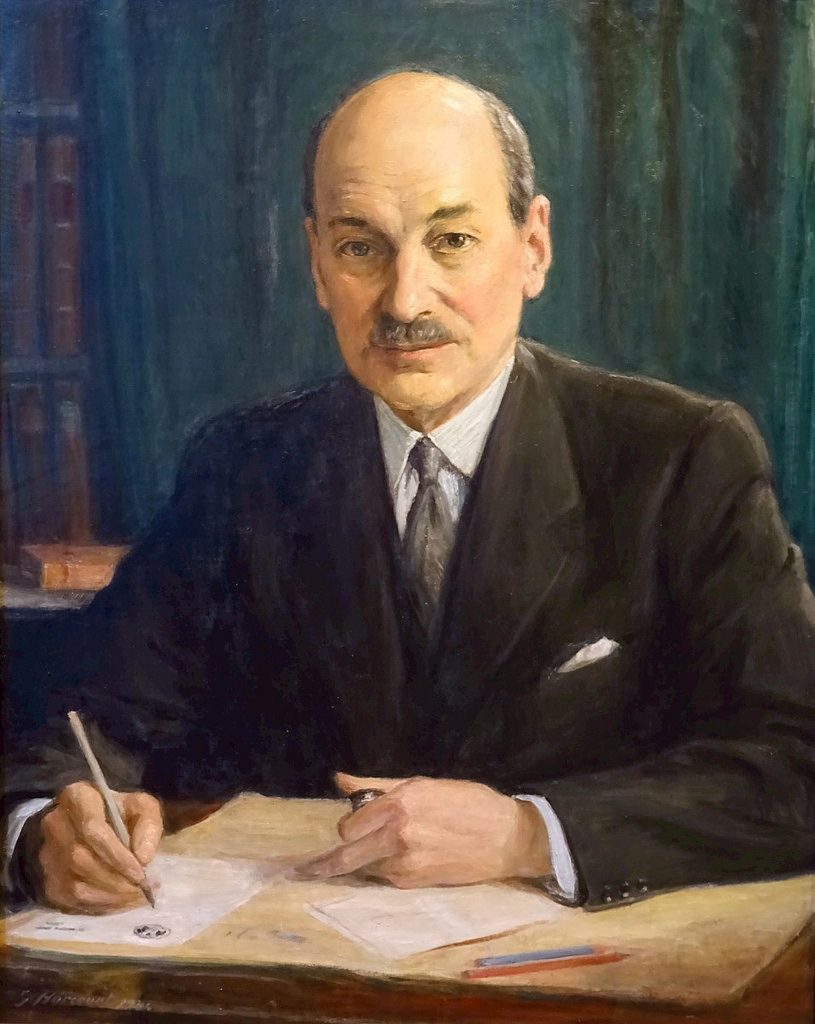

Clement Attlee

Ally and Rival

Perhaps the most interesting relationship between Churchill and those who followed him is the one he had with Clement Attlee. Without Attlee’s backing, it is far from certain that Churchill would have become Prime Minister in 1940. Attlee went on to serve with distinction in the War Cabinet, including as Deputy Prime Minister from 1942 onwards. His loyalty saw him back Churchill on major issues of strategy in discussions with the chiefs of staff, as well as facing down criticism from Labour colleagues. Despite this wartime unity, Attlee went on to become one of Churchill’s greatest political rivals, beating him in both the 1945 and 1950 general elections before the Conservatives were returned to power in 1951.

As may be expected of such a rival, many cutting assessments of Attlee have been attributed to Churchill. Two are well known: “An empty cab drew up and Mr. Attlee got out” and supposedly describing the Labour leader as “a sheep in sheep’s clothing.” Neither of these, however, can correctly be attributed to Churchill.2 When his private secretary “Jock” Colville repeated the first of these two jests in his master’s presence, Churchill replied: “Mr Attlee is an honourable and gallant gentleman and a faithful colleague who served his country well at the time of her greatest need. I should be obliged if you would make it clear whenever an occasion arises that I would never make such a remark about him, and that I strongly disapprove of anybody who does.”3 Churchill did quip to President Truman that Attlee was a modest man “with much to be modest about,” but that seems to speak more to his quick wit than to his view of Attlee.4

2024 International Churchill Conference

The genuine nature of Churchill’s esteem is reinforced by the fact that he continued to defend Attlee even in private and amongst fellow Conservative politicians. On one occasion at Chartwell after the war, the Conservative MP for Sevenoaks, Sir John Rogers, called the Labour leader “silly old Attlee,” only to be admonished by Churchill and told that if he repeated that again he would not be invited back.5 Perhaps most tellingly, when asked in 1946 by godson Freddie Birkenhead which of his former Labour colleagues he respected most, Churchill did not hesitate in naming Attlee, as opposed to the expected answer of Ernest Bevin.6 Such respect across the political divide was wholeheartedly reciprocated. Paying tribute in the House of Lords following Churchill’s death, Attlee expressed his pride “to have lived with him and, above all, to have worked with him” and declared that, “by any reckoning, Winston Churchill was one of the greatest men that history records.”7

This bond of mutual respect between these two giants of the twentieth century, formed in wartime, endured to the end of both men’s lives. Yet they were still able to clash as both colleagues and adversaries with irritation and asperity. Whilst there was significant agreement on foreign affairs and defence issues, domestically they often returned to arguments down established party lines. Some of these, such as nationalisation of industry, continue today. Commenting on the record of Attlee as Prime Minister in the 1951 Conservative Party Manifesto, Churchill was— unsurprisingly, given that this was a campaign document—scathing. He argued, “The attempt to impose a doctrinaire Socialism upon an Island which has grown great and famous by free enterprise has inflicted serious injury upon our strength and prosperity.” Churchill’s remarks, it should be noted, contained no personal antipathy. He went out of his way to acknowledge that Attlee was “well-meaning.” But Churchill doubled down on his criticism of socialism, arguing that “there is no doubt that in its complete development a Socialist State, monopolising production, distribution and exchange, would be fatal to individual freedom.”8

A conversation that supposedly took place around this time highlights the willingness of the former colleagues to spar in a good-natured way. Churchill is said to have encountered Attlee at the urinal in the Members’ toilets in the House of Commons and shuffled as far away as possible. Attlee said: “Feeling standoffish today, are we, Winston?” to which Churchill replied with characteristic wit: “That’s right. Every time you see something big you want to nationalise it.”9

The two men never became a fixture of one another’s social circles, which is perhaps no surprise given how different their personalities were. Despite Churchill’s fondness for entertaining at Chartwell, Attlee’s name does not appear in the visitors’ book of the house. Churchill also failed to invite Attlee to join the Other Club. When Colville suggested that he do so, Churchill replied, “I think not. He is an admirable character, but not a man with whom it is agreeable to dine.”10 Such a comment perhaps sums up in a single sentence the relationship these two men had.

Anthony Eden

The Heir Apparent

Anthony Eden’s relationship with Churchill is undoubtedly best viewed through his position as Churchill’s heir apparent. From as early as 1940, Churchill made promises to Eden about him being his successor as Prime Minister and leader of the Conservative Party. Eden wrote in his diary that Churchill had confirmed “he would not make L[loyd] G[eorge]’s mistake of carrying on after the war, that the succession would be mine.”11 Similar promises were to be made over the next fifteen years, probably made with the intention of following through, at least at the moment. Churchill was well aware of Eden’s increasing impatience to succeed him and joked to sculptor Oscar Nemon, “I really should resign. One cannot expect Anthony to live forever.”12

When Eden was first appointed as Foreign Secretary by Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin in 1935, Churchill expressed doubts about his abilities, writing to Clementine: “Eden’s appointment does not inspire me with confidence,” adding “I expect the greatness of his office will find him out.”13 By the time of Eden’s resignation from that office in 1938, however, Churchill’s view had been turned on its head and he felt real concern. He later wrote: “There seemed one strong young figure standing up against long, dismal, drawling tides of drift and surrender, of wrong measurements and feeble impulse….Now he was gone. I watched the daylight slowly creep in through the windows, and saw before me in mental gaze the vision of Death.”14

Eden went on to become one of Churchill’s most trusted lieutenants and was appointed by him to some of the most senior roles in government, including Foreign Secretary on two separate occasions and Deputy Prime Minister in 1951. During the war, Churchill even advised the King that Eden should replace him as Prime Minister should he be killed, saying that he was “an outstanding minister of the largest political party in the House of Commons and in the National Government.”15 Equally, during his period as Leader of the Opposition, Churchill delegated heavily to Eden. Although they naturally clashed at times whilst working alongside one another, there can be no doubt about the high regard that Churchill had for Eden’s ability.

After the war and despite what he had once said, Churchill found reasons to hold on to office. This went on during six years of opposition and Churchill’s return to Downing Street in 1951. Delays and excuses continued even as Eden became Churchill’s nephew-in-law following marriage to Clarissa Churchill in 1952. This caused significant tension between the two men. By the end, Churchill felt pushed out and developed what Colville described as a “cold hatred of Eden.” Churchill biographer Roy Jenkins—himself a former Cabinet minister—believed that this was an oversimplification. The relationship included a significant amount of appreciation and respect from years of the two men working successfully together.16 Nonetheless, Churchill’s change in his feelings towards Eden was real and perhaps explains why on his last evening in Downing Street, having entertained the Queen at a farewell dinner, Churchill said to Colville, “I don’t believe Anthony can do it.”17 This proved prescient. The strain of being the longest serving prime minister-in-waiting in British political history, along with serious illness, likely contributed to Eden’s unsuccessful period in No. 10. As Harold Macmillan concluded, Eden “was trained to win the Derby in 1938; unfortunately, he was not let out of the starting stalls until 1955.”18

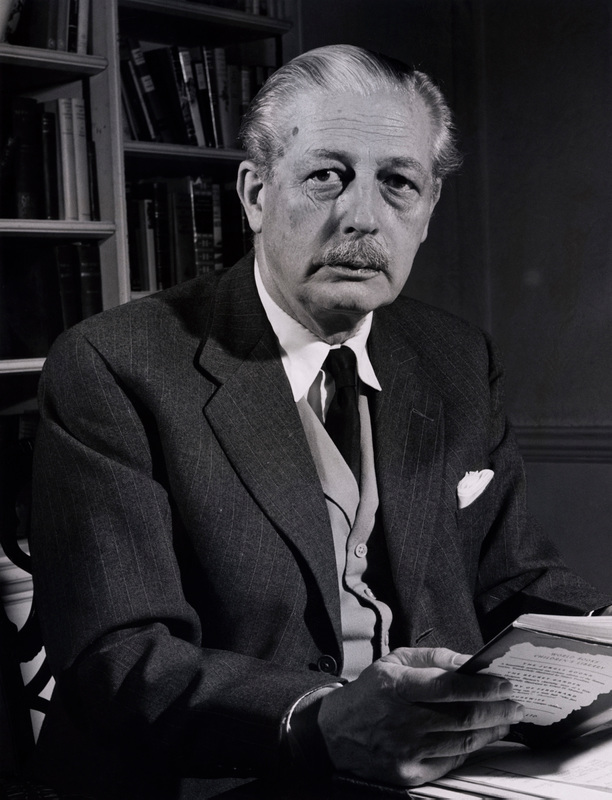

Harold Macmillan

The Rising Star

Like Eden, Harold Macmillan was another acolyte of Churchill’s who helped bring Chamberlain down over appeasement. Shortly before the Norway debate in 1940, Macmillan told Churchill, “We must have a new prime minister and it must be you.”19 Despite having first entered parliament almost fifteen years earlier following gallant service in the First World War, Macmillan had always remained on the backbenches. It was only when Churchill became Prime Minister that Macmillan was invited to join the government as junior minister in the Ministry of Supply. Observing this change in his career prospects, Macmillan is reported to have made the ill-advised remark to Churchill that “You and I owe Hitler something. He made you Prime Minister and me an under-secretary. No power on earth, except Hitler, could have done either.”20 Macmillan continued to rise within the government, however, achieving cabinet rank as Minister Resident in the Mediterranean in 1942. He also served a brief stint as Secretary of State for Air in Churchill’s 1945 caretaker government.

Although he lost his seat in 1945, Macmillan soon returned to the House of Commons, and his rise continued. He was reportedly Churchill’s first choice for Conservative Party Chairman in 1946 when, as Leader of the Opposition, Churchill described Macmillan as “one of our brightest rising lights.”21 While the Conservatives remained in opposition between 1945 and 1951, some of the younger Tory backbenchers expressed a desire for a fresh start with Macmillan as Party Leader. “They feel that Winston is too old and Anthony [Eden] too weak,” observed Harold Nicholson, “They want Harold Macmillan to lead them.”22 Macmillan, however, never truly displaced Eden as Churchill’s heir apparent. Instead, he continued to rise in government. Following Churchill’s return to power in 1951, Macmillan was made Minister of Housing and Local Government and given the task of delivering on a Tory campaign commitment to build 300,000 new houses a year. Churchill said to him, “It is a gamble—it will make or mar your political career, but every humble home will bless your name if you succeed.”23 Macmillan got the houses built, and this has formed part of his legacy. Churchill rewarded proven ability by promoting Macmillan to serve as Minister of Defence.

Despite owing his advancement to Churchill, Macmillan was one of the few members of the Cabinet to urge the Prime Minister to make a decision on when to stand down. A 1954 letter from Macmillan on this subject elicited a stern response from Churchill: “I was well aware of your views.”24 Macmillan’s efforts to speak to Churchill on the subject were not well received either. Privately, the Prime Minister began to remark that Macmillan was “very ambitious.”25

Suspicion was understandable since it had become conceivable that Macmillan could be a contender for the top job. At least in part, however, Macmillan was motivated by his concern for Churchill. In his diary Macmillan wrote that he was saddened to see the great leader’s powers in decline: “it breaks my heart to see the lion-hearted Churchill begin to sink into a sort of Pétain.”26 This is not out of character, given that Macmillan showed great personal kindness towards Churchill over a long period of time. Macmillan had been one of the 140 friends who contributed to the gift of a new car to Churchill in 1932. As Prime Minister in 1962, Macmillan ordered an RAF Comet air ambulance to fly Churchill home from Monte Carlo, where he had experienced a bad fall.

After he did finally leave Downing Street in 1955, any lingering resentment Churchill may have felt towards Macmillan did not prevent him from believing that Macmillan should himself become Prime Minister after Eden. “I’d like to see Harold Macmillan as Prime Minister,” Churchill said to Lord Moran in 1956.27 In the following year, this became a reality after Eden’s resignation over Suez. At the time Macmillan told the Queen that his administration might not last more than six weeks. In fact, it lasted more than six years. Perhaps fittingly, Churchill’s final re-election to the House of Commons came in 1959 under the leadership of his former protégé, who won a 100-seat majority.

Alec Douglas-Home

The Unexpected Prime Minister

Unlike Attlee, Eden, and Macmillan, Alec Douglas-Home did not hold any significant role in Churchill’s wartime government. Having been Neville Chamberlain’s Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) at both the Treasury and No. 10 in the 1930s, he was described as “invariably delightful” by Colville but hardly seen as a potential ally of the incoming Prime Minister in 1940. Indeed, following Churchill’s appointment to the top job, Douglas-Home had drunk a toast with colleagues to the “King over the Water” and remained Chamberlain’s PPS until the former Prime Minister left the War Cabinet due to ill health. Douglas-Home then volunteered for military service, but a need for significant spinal surgery put this out of the question and restricted his political activities. He did not attend the House of Commons again until 1943 and remained on the backbenches until the end of the war in Europe.

Churchill appointed Douglas-Home to a junior Foreign Office post in the brief caretaker government of 1945. When Churchill returned to power in 1951, he appointed Douglas-Home to serve as Minister of State for Scotland. By this time, Churchill had developed a positive view of the Scottish nobleman but did not mark him out as a future PM. This is not surprising given that by the time of his promotion to the Cabinet, the new Scottish Minister had also succeeded to become the fourteenth Earl of Home. “Your Home, Sweet Home seems to be doing well,” was Churchill’s fond, if slightly patronising assessment of the earl’s performance at the Scottish Office.28

Douglas-Home’s real rise came after Churchill retired. He served successively as Commonwealth Secretary under Eden and Foreign Secretary under Macmillan before renouncing his peerage in 1963 to become Prime Minister himself. By then, Churchill was in sharp decline and contemplating retirement from the Commons.

Douglas-Home and Churchill were never close. Not only had there been significant policy differences, the two men exhibited very different personalities. Douglas-Home appears never to have been invited to Chartwell. There was, however, mutual respect. As one of Britain’s most unexpected prime ministers, Douglas-Home was among the politicians to dine with Churchill at Hyde Park Gate in 1964 and present him with a resolution of the House celebrating Churchill’s six decades of parliamentary service following his final visit to the House of Commons. Churchill lived to see just one more Prime Minister in Downing Street, Harold Wilson, but it was Douglas-Home who brought down the curtain on thirteen years of Conservative government, which had begun with Churchill’s post-war return to power.

Edward Heath

Generations Apart

Edward Heath was clearly of a different generation from Churchill. By the time Heath was born in 1916, Churchill was in his forties and had already held several high offices of state. Heath did not enter the House of Commons until 1950 and received his first front bench appointment from Churchill in 1951, when he joined the Whips’ office in opposition, and continued there when the Conservatives entered government later that year. Heath continued as a junior whip until he was promoted to Chief Whip shortly after Eden took over from Churchill. There was, therefore, little personal connection between Churchill and Heath. Indeed, Heath was such a junior figure at the time that he does not merit a single mention in Colville’s Downing Street Diaries.

Nevertheless, Churchill obviously made an impact on Heath. As a young whip, Heath was asked to give the vote of thanks following Churchill’s speech to the 1953 Conservative Party Conference, the Prime Minister’s first public appearance following his stroke. Heath praised the leader’s “magnificent speech,” as would have been expected, but he went much further by expressing real admiration for Churchill, saying, “Every one of us here today knows that the sum of [the Government’s achievements] is due to his vision, to his inspiration and to his leadership throughout the past two years.”29

In later years Heath and Churchill corresponded and dined together. The Chartwell visitors’ book records that Heath was a regular guest in the late 1950s and early ’60s including a visit on Boxing Day in 1961.30 Heath also became a member of the Other Club in 1960. Since Heath did not become Leader of the Conservative Party until after Churchill’s death, however, their friendship is unlikely to have produced any direct political guidance. In any case, Heath did maintain a friendship with Clementine Churchill until her death in 1977.

Churchill’s governments continued to influence British politics through the latter half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. Many who served under his leadership went on to hold higher office. This goes beyond the five Prime Ministers described here. For example, the last surviving member of Churchill’s governments, Lord Carrington (Foreign Secretary under Margaret Thatcher), was still contributing to the House of Lords almost sixty years after Churchill left office. Many more continue to draw inspiration from Churchill to this day. Former Prime Minister David Cameron—born well after Churchill died—said, “when faced with difficult decision I often find myself asking—what would Winston do.”31 Current Prime Minister Boris Johnson wrote a best-selling biography of the man he describes as a “hero.”32 No doubt occupants of No. 10 will continue to find inspiration from the life and legacy of Winston Churchill for years to come.

Endnotes

1. https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/quotes/churchill-one-liner-quotes/, accessed 9 April 2020.

2. https://richardlangworth.com/ quotes-churchill-never-said-1, accessed 9 April 2020.

3. Robert Andrews, The New Penguin Dictionary of Modern Quotations (London: Penguin, 2003), p. 106.

4. Richard Langworth, ed., Churchill in His Own Words (London: Ebury Press, 2012), p. 321.

5. Leo McKinstry, Attlee and Churchill: Allies in War, Adversaries in Peace (London: Atlantic Books, 2019), pp. 15–16.

6. Andrew Roberts, Churchill: Walking with Destiny (London: Allen Lane, 2018), p. 894.

7. https://winstonchurchill.hillsdale.edu/clement-attlee-part-2/, accessed 9 April 2020.

8. Conservative Party, 1951 Conservative Party General Election Manifesto.

9. https://richardlangworth.com/ urinal, accessed 9 April 2020.

10. Andrews, p. 106.

11. Roberts, p. 599.

12. Ibid., p. 947.

13. Mary Soames, ed., Speaking for Themselves: The Personal Letters of Winston and Clementine Churchill (London: Black Swan, 1999), p. 402.

14. Winston S. Churchill, The Gathering Storm (London: Cassell, 1948), pp. 257–58.

15. Roberts, p. 735.

16. Roy Jenkins, Churchill (London: Macmillan 2001), p. 886.

17. John Colville, The Fringes of Power (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1985), p. 708.

18. D. R. Thorpe, “The Conscience of Politics: Sir Anthony Eden as Heir Apparent,” Finest Hour 172, spring 2016, p. 17.

19. Boris Johnson, The Churchill Factor (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2015), p. 54.

20. Vernon Bogdanor, “Harold Macmillan obituary,” Guardian, 30 December 1986.

21. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. VIII, Never Despair, 1945–1965 (London: Minerva, 1988), p. 227, n. 1.

22. Harold Nicolson, Diaries and Letters, 1945–62 (London: Phoenix, 2009), p. 32.

23. Harold Macmillan, Tides of Fortune (London: Macmillan, 1969), p. 364.

24. Jenkins, p. 879.

25. Thorpe, p. 17.

26. D. R. Thorpe, “Supermac’s Ascent,” Daily Telegraph, 2 June 2003.

27. Jenkins, p. 902.

28. David Dutton, Douglas Home (London: Haus, 2006), p. 19.

29. Anthony Seldon, Churchill’s Indian Summer (London: Faber and Faber, 2010), p. 45.

30. National Trust, Chartwell Visitors Book.

31. Letter from David Cameron to Katherine Carter, 12 September 2014, author’s collection.

32. Johnson, p. 4.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.