Finest Hour 193

The Tonypandy Riots, 1910 – Winston Churchill’s Nemesis

Tonypandy riots

August 30, 2022

Finest Hour 193, Third Quarter 2021

Page 15

By Dai Smith

Dai Smith was born in Tonypandy in 1945. He has been a Professor of Modern History at both Cardiff and Swansea Universities. His numerous publications include a history of the South Wales miners in the twentieth century.

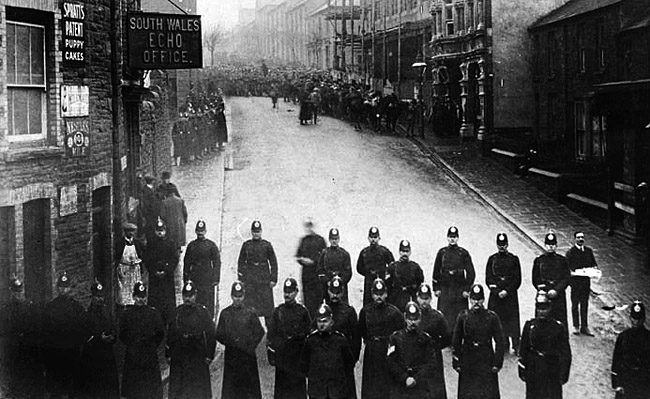

In January 1949, four years into the Labour Government of Clement Attlee created by a landslide electoral victory over Winston Churchill’s Conservative Party in 1945, the Lord Mayor of Cardiff proposed to his Council that a new road development in the city centre be named “Churchill Way.” The motion was carried on a split vote, with one dissenting councillor stating, “Tonypandy men had long memories.” Long enough, it seemed, to reverberate through the Rhondda Valley after two world wars in echo of the year-long coal strike of 1910–11 and the infamous riots of November 1910. At that time, the commercial high street of the mid-Rhondda town of Tonypandy was wrecked, and both Metropolitan Police and the military were sent in by Winston Churchill, then the Liberal Home Secretary.

What followed from that action was to haunt Churchill four decades later. He tried to exorcise the accusing spirit of what he and his supporters took to be both false memory and unfair interpretation. In a gracious reply to the Lord Mayor in February 1949, acknowledging the honour being paid to him, the great war leader—but then defeated politician—wrote: “I see that one of the Labour men referred to Tonypandy as a great crime I had committed in the past. I am having the facts looked up and will write to you again upon the subject. According to my recollections the action I took at Tonypandy was to stop the troops being sent to control the strikers for fear of shooting. Instead I sent Metropolitan Police who charged with their rolled mackintoshes and no one was hurt. I will let you know the result of my researches.”

Exactly one year later, in February 1950, a General Election took place, which eventually returned the incumbent Labour Government with a much-reduced parliamentary majority but on the highest percentage of the popular vote ever recorded— and more than a million votes beyond the Conservative total. During the campaign Churchill gave the electorate the further benefit of his researches into the events of 1910–11 that took place in the coalfield just twenty miles north of Cardiff. This time, addressing a rally at the Ninian Park football ground of Cardiff City, he stoked the fires of controversy in public. His account was adamant and clearcut. Troops had been held back by him, at first, and later had no direct contact with the men on strike. A few bloody noses were all the Metropolitan Police had caused.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Churchill thus gave his rapt audience what he called “the true story of Tonypandy, in order, to replace in Welsh villages the cruel lie with which they have been fed all these long years.” This was not some spontaneous reference made in the course of a long speech, nor were there any hecklers to whom he was merely responding. In 1950, the linkage between the once-and-future Prime Minister and a distant dispute was still a live issue, even one toxic enough to have all Conservative candidates briefed about the Cambrian Combine strike and for the Conservative Party to issue a circular stating that Churchill “allowed the troops to be drafted into the area as a reserve to the police, but they were not used.”

The righteous indignation of his opponents swiftly followed. The Rhondda West Constituency Labour Party issued to the local voters their own “Manifesto” as a “Tonypandy Reply” to “let Churchill know that you remember 1910 and the part he played in requesting the use of military forces.” Ness Edwards, the Labour MP for Caerphilly and himself a former historian of the South Wales Miners Federation (SWMF), told the press that “The miners are so infuriated…that Mr Churchill has inflicted a fatal blow to Tory aspirations in the South Wales coalfield (and that) the facts (show) Mr Churchill did use the military against the miners at Tonypandy, and the miners will never forget it.”

It would seem that between assertion and counter-claim, between myth and actuality, only one side could possibly be in the right. Enough documentation and evidence, official and reported, enough testimony from participants and witnesses existed to be placed on the scales and assessed accordingly. What, however, was weighed in the balance when the thumb prints of the two sides were also accounted for was something more intangible: motivations and perceptions, intentions and outcomes, ignorance and knowledge. Both parties, as it turns out, had some justification to remember Tonypandy in their own particular way. But, in the final analysis, only one of the contenders was increasingly desperate for self-justification. By 1950 the die was cast, the popular verdict was in, and on the cinema screens of South Wales whenever Churchill appeared on the Movietone newsreels his image was booed, and his very name met with the hiss of collective hostility. To understand exactly why this had occurred, the significance of what was at stake in Tonypandy in 1910 has first to be understood in its own contemporary terms.

Origins of the Dispute

By the late summer of 1910, eighty men in the Ely pit, one of four pits in the Naval Colliery complex to the south of the settlement of Tonypandy, had been engaged for some months with management in negotiation over the cutting price per ton to be paid for the working of a new seam of coal. This Bute seam contained a great deal of stone that was, effectively, dead work in so-called “abnormal places.” The differential in price was between 1/9d and 2/6d per ton. What may seem an abstruse matter of Edwardian industrial relations was, in hard fact, the basis for natural justice in the mining industry, the pivot for widespread demands for a minimum wage, and the buffer against which conciliatory labour relations would founder before and after the Great War.

In the more immediate sense this limited matter of concern in the Ely pit concealed a wider agenda. This was not the doctrine of syndicalism, or workers’ “control,” with which, after the publication of The Miners’ Next Step in 1912, Tonypandy also became synonymous. The real issue was the growing, overweening power of coal capitalism, as represented by the amalgamation of smaller concerns into integrated enterprises in which the sinking of shafts, the getting of coal, the rail transport, and shipping and sale of the mineral were all vertically combined. Nowhere was this more so than in mid-Rhondda, where D. A. Thomas, a coalmine owner and Liberal MP for Merthyr Boroughs and then for Cardiff, had built on his inherited Cambrian Colliery pits in nearby Clydach Vale to incorporate the Glamorgan Colliery pits to the north in Llwynypia, as well as those of the Naval Colliery to the south and, over the mountain from Tonypandy, a further colliery in Gilfach Goch. This meant the direct employ of twelve thousand men in the Cambrian Combine, all under an autocratic general manager in the form of the unyielding Leonard Llewellyn.

Rhondda supplied a third of all coal extracted in the United Kingdom, and the Cambrian Combine, largely for export, supplied fifty per cent of Rhondda’s total. Economically, Tonypandy was not “an obscure township.” This place, at this time, was an epicentre of British and Atlantic capitalism. Profit was all, and baseline profit was, in a labour intensive industry, utterly dependent upon control of the wages of the men. Compromise would be limited, and confrontation, so far as these mutually indemnified South Walian coalmine owners were concerned, was acceptable if their ultimate victory could be predicted.

To force the issue, from 1 September 1910, not only the eighty men in dispute but all 800 men in the Ely pit were locked out by the Combine. By 1 November, as a result of staged responses, the men in all the pits of the Combine’s collieries had agreed to strike in solidarity. The rationale of the men was that caving in to the cutting price offered would see similar imposition of terms elsewhere. Indeed, when the earlier absorption of the Glamorgan collieries into the Cambrian Combine had seen wage levels threatened there, only a strike in 1908 in the Llwynypia pits had forced a managerial climb down in the face of a possible escalation of the strike on a wider basis. A potential combination of trade union force had been readied versus the Combine, which was, in 1908, not yet ready to accept such a challenge. By 1910, however, the owners certainly were ready.

For the men’s part a mass meeting, organised by their joint leaders in a new committee of command and purpose, decided to make full use of the Trades Disputes act of 1906 to picket all the collieries into a complete stoppage. This was to include enginemen, stokers, boilermen, and officials so as to bring the possibility of any working to a halt. Crucially, it was agreed attempts to use or bring in non-compliant or blackleg labour would be fiercely resisted by mass picketing of all the collieries.

In full understanding of the implications of this show of power, and in the light of concerted union action in the adjacent Cynon Valley, the mine owners made two tactical moves. The first was to inform Military Command, via the Chief Constable of Glamorgan, as was accustomed practice, and as early as 2 November, that there was likely to be a request for military support of the police being drafted into the area. The second move was to decide that the manner in which they would respond to the strike would be to invest all available police strength, local and imported, within the perimeters of only one of their collieries, abandoning the rest thereby, and so make the Glamorgan Colliery a citadel into which, directly by rail, blackleg labour could be brought as a deliberate act of provocation. The latter was the name of the game from the beginning as, after mass picketing did stop at all other collieries by 7 November, any requests by official pickets to talk with those at work were peremptorily dismissed out of hand by Leonard Llewellyn, whilst Captain Lionel Lindsay, the aggressive and malleable Chief Constable, ordered his officers to charge indiscriminately into the large crowds gathering outside the Glamorgan Colliery on Monday, 7 November and again on Tuesday the 8th. This last ferocious fracas led to a fatality, a miner felled by a blow to the head from a “blunt object,” caused severe and several bodily injuries and, as a byproduct, triggered the “sacking of Tonypandy.”

Enter the Home Secretary

It was only after these related but disparate events that Churchill irrevocably entered the fray. Home Secretary since February of that year, Churchill was intent on being a peacemaker but was now duped into taking a stance that he had initially spurned as he was engulfed by a conflict he neither fully understood nor controlled. It was the local coalmining interest which, above all else, wanted the army to come to Tonypandy. Unlike any extra police—drawn from Bristol, Swansea, Gloucester, and the Met, a force of nearly 1,500 men under Lindsay by 15 November—all of whom would be a cost to Glamorgan County ratepayers, the military would be a free gift for the securing of colliery property, a deterrent to the demonstrations by thousands who might thus be dispersed and, as a back-up to police prevention of all peaceful persuasion to cease working, a virtual guarantor of the strikers’ ultimate defeat. The latter fact would be the cause of Churchill’s enduring reputation in “the long memories” of “Tonypandy men.”

It was certainly not the memory Churchill would have wished to induce as he was forced to react to unfolding events. To begin with, he had no wish, with a General Election looming in December, to endanger any Liberal sympathies crucial to ensuring the continuity of Prime Minister H. H. Asquith’s government. He was well aware, too, that Asquith, when Home Secretary in 1893, had been labeled “Featherstone Asquith” after troops shot and killed two miners in that minor West Yorkshire colliery town. Further, Churchill’s broad sympathies at that time were with the miners, whose appeal for an eight-hour day he had supported, as had his father before him. Churchill proudly boasted of the time in 1908 when he had attended and spoken at the annual miners’ rally held in mid-Rhondda. So, when he had been informed on the morning of Tuesday, 8 November that the Chief Constable’s request for troops had already been sanctioned by the War Office and that two companies of infantry were entrained, Churchill summoned Richard Haldane, the War Secretary, to the Home Office and, in agreement, they halted the enroute troop train at Swindon. Only 200 cavalry were allowed to proceed further, but under orders to remain in Cardiff. In addition, Churchill instructed that 200 Metropolitan policemen and ten mounted constables travel forthwith from London to Pontypridd to assist if necessary the irate Lindsay and to placate the incensed Llewellyn.

Churchill’s own message setting out his decisions was read out to a mass meeting of the strikers held on the afternoon of 8 November in the mid-Rhondda Athletic Ground. It had been warm in tone, if slightly ambivalent, as he both referred to himself as one of “their friends here” in Westminster and said that soldiers were being held back “for the present,” with only police being sent into the coalfield. To the Chief Constable, in a telegram sent one hour later, Churchill was firm about infantry not being used “till all other means have failed,” but left a door open by saying the cavalry would remain in “the district pending cessation of trouble.” Major General Nevil Macready was to be in sole command of the “military (who) will not…be available unless it is clear that police reinforcements are unable to cope with the situation.” The Chief Constable of Glamorgan would not be one to let any opportunity to capitalise on that loophole slip, and so Churchill’s first plan had quickly unraveled as local police aggression brought about a premature denouement.

From late afternoon to dusk on 8 November, a crowd of some 8,000 had gathered around the entrance to the extensive Glamorgan Colliery. Inside the gates, Lindsay commanded about 100 constables, some mounted, and backed Llewellyn in his consistent refusal to allow selected pickets onto the premises to talk with those at work. When the crowd began to stone the Power House, where the electric engine was maintained to prevent the colliery from flooding, Lindsay chose to drive two separate cohorts of men into the crowd to drive them the quarter-mile distances south to Tonypandy and north to Llwynypia. This led to the pitched battle clashes between baton-wielding police and pick-axe-handling miners. Casualties were many and frequent, with on-looking women and bystanders randomly involved. Trouble only ceased around 8 pm, when the police retreated into the colliery gates.

False Step

The narrative and timing of these events is the crux to comprehending Churchill’s next—and false—step. In essence, the version told him by the police and the mine owners was believed: that “a mob” setting out to invade and capture the Glamorgan Colliery had been foiled in their undertaking by a small but gallant force of police which, next time, might be overwhelmed. Telephonic communications to this effect from Lindsay in Tonypandy, and a telegram sent at 7:45 pm from the Stipendiary Magistrate, which confirmed he would be ready with fellow magistrates to read the official Riot Act upon the advent of troops, caused Churchill, in Westminster, to reverse his decision around 8 pm and telegram General Macready to move “all the cavalry into the district without delay…if the Chief Constable desires it.” The Chief Constable certainly did.

Consequently, in addition to the 200 Metropolitan policemen who had arrived in Tonypandy by 10 pm—too late to assist in anything that night—a squadron of the 18th Hussars were patrolling the streets by noon the next day. Then, in short order, by Wednesday, 9 November, separate companies of the Royal North Lancashire Regiment, the Lancashire Fusiliers, the West Riding Regiment, the Devonshire Regiment, and the Royal Munster Fusiliers were also on hand, either locally or on standby elsewhere in South Wales. Those desiring the presence of troops saw their task accomplished, especially Leonard Llewellyn, who commented acidly that “Mr Winston Churchill’s actions (in halting the troops) have really made things worse,” since on Sunday, 6 November he had personally “applied for military and saw the Magistrates on the Monday morning, and I told them of the seriousness of the case, and my complaint is that none of this bloodshed would have happened if the military had been here.”

What is clear is that the riot referred to by the local law authorities, and the bloodshed consequently involved, is that outside the Glamorgan Colliery and not the collective and directed rage against the local “shopocracy,” which followed, sequentially but not causally, in the township. Churchill’s change of response was a reaction to the claim of a direct threat to the Colliery premises and to the fate of the 300 horses artfully gathered underground there by Llewellyn and allegedly in mortal danger from flooding. The press had a field day on that canard, too. Churchill had, therefore, on the night of 8 November intervened directly in the strike and, although he did not align himself with the ongoing, deliberately confrontational tactics of the mine owners, he was now tarred himself in the eyes of the community. The relationship between the clashes around the conduct of the strike and the rampaging riot up and down Tonypandy’s High Street on the night of 8 November is the final clarification here needed.

Perceptions

The social pathology indicated by the smashing and looting of the shops is revelatory of a community fracture inimical to the self-image cherished by Liberal and Nonconformist Edwardian Wales. In sum, the communal leadership of a shopocracy was directly challenged in a carnival of disorder. Those shopkeepers who were multiple homeowners for purposes of rent, or operated a secret black listing system for bad debtors, or enjoyed a controlling level of political representation (enjoying civic and social intimacy with both mine owners and officials), or who were thought to have expressed disdain for the men on strike, were purposefully targeted. Tellingly, others were not. This world-turned-upside-down was, in this fashion, on show for one night only, although it had wider social and cultural repercussions during the strike and thereafter. The fury unleashed was violent but also selective. Bewildered analysts at the time, from all parts of the spectrum, could only, and quite inadequately, blame “strangers” or “drunks” or “youths,” and spirit away thousands of actual participants so that they dwindled to imagined hundreds. Churchill wrote reassuringly to the King, who was deeply concerned about the fate of the horses underground, to deplore the “insensate” action of a mob against innocent shopkeepers for whom they could have no rational “animosity.” Explanations for this redefining of community relations would have to wait on forensic historical research. Expressed innocence, at the time, was a whitewashing, rather elastic, concept.

Nonetheless, its simplifying of a crowd into a mob and a directed, conscious knowledge of local circumstances into a psychological frenzy was a convenient explication of social fracture if the wider strike narrative, as set out by such as the Combine’s eloquent contemporary defender, the newspaperman David Evans, was to be accepted—as indeed it was for more than seventy years. The key point of Evans’ Labour Strike in the South Wales Coalfield 1910–11, written hard on the heels of the strike’s ending in September 1911, was that the riot in the town occurred solely because the purpose of the (other) riot at the colliery had been thwarted. It was, therefore, to be all Churchill’s fault by not dispatching the military beforehand as requested by owners, police, and magistracy.

Churchill could, however, take more than a measure of comfort from the messages sent to him by the levelheaded General Macready, who quickly took a very dim view of the high-handedness of Llewellyn and Lindsay as to the deployment of his soldiers. Nor did Macready believe their version of what had actually unfolded. That was, in fact, a pup they had sold the distant Home Secretary on the evening of 8 November. In his memoirs, Annals of an Active Life (1924), Macready forthrightly contradicted them, and the account of their amanuensis David Evans:

Investigation on the spot convinced me that the original reports regarding the attacks on the miners on November 8th had been exaggerated. What were described as “desperate attempts” to sack the power-house at Llwynypia proved to have been an attempt to force the gateway (and) had the mob been as numerous or so determined as the reports implied, there was nothing to have prevented them from overcoming the whole premises. That they did not was due less to the action of the police than to the want of leading or indication to proceed to extremities on the part of the strikers.

Churchill was given every indication of the exact temper of the dispute, so far as the strike leaders were concerned, when, on 9 November, a delegation attended a convened meeting at the Board of Trade. Reconciling the two sides, a move spearheaded by Rhondda MP William Abraham (“Mabon”) the Lib-Lab elder statesman and President of the SWMF, proved to be a step too far, but what was underlined by the men’s delegation was that no objections were made by them to police protection of colliery property, only to police prevention, at the owners’ behest, of the ability to picket, as guaranteed by the far-reaching Trade Disputes Act of 1906. That was to remain the nub of it all.

Churchill showed that he understood this, and even to an extent sympathised with the complaint. The law, after all, could be invoked in more than one way. He asked the Chief Constable to be circumspect by not making “small things” a cause of resentful reaction, and he chafed at the disrespect shown to Macready’s cooler approach when labour was imported by train or fresh working—all without consultation—was undertaken. Churchill had written in an evenhanded manner on 16 November to Macready to set out his objective of having the troops there solely to hold the ring:

You should remember that the owners are within their legal rights in claiming to import labour but that you are entitled to judge time, manner and circumstances of such importation in order that no breach of peace may be unnecessarily provoked and to ensure that the authorities responsible for keeping order have adequate forces upon the spot. With this leverage you might be able to restrain or at any rate delay injudicious action on part of the owners… you should note my pledge that peaceful picketing will be protected.

Arguably the circle could not be squared. In the months which followed, amongst a plethora of incidents and prosecutions and false imprisonments, mostly orchestrated by Lindsay in his capacity as the law enforcement arm of the owners, two further confrontations stand out in which the outcome of the troops’ presence in mid-Rhondda was all too readily apparent to the strikers. There were running battles between the police and crowds determined to stop the arrival by train of blackleg labour on 21 November and again, in the strike’s last major incident, on 25 July 1911. In both instances, as the police fell back in disarray, Macready took command. In November, in the absence of the Chief Constable, he ordered up fifty Metropolitan police, batons not mackintoshes to hand, and then resolved the issue by sending half a company of the Lancashire Fusiliers to the hot spot of Penygraig, a company of the West Riding into Tonypandy, with a further squadron of Hussars to assist, whilst he also stopped “the eleven men obtained by Mr Llewellyn from Cardiff…at Pontypridd.”

In July 1911, as a result of managerial refusal to allow any persuasion of or meeting with blacklegs at the Ely pit of the Naval Colliery, where the strike had been occasioned in the first place, a crowd of up to 5,000 stoned the pit and its protective police cordon and rolled boulders down the mountainside from above the colliery. The military again were called in, and a company of Somerset Light Infantry outflanked the surprised strikers. Armed with ball cartridge rifles and bayonets, they enveloped the crowd from above, driving them with their fixed bayonets down into the streets for the waiting police to charge their scattered ranks.

Immense suffering, hardship, and privation finally took their toll. The Cambrian Combine strike petered out in despair and was formally ended after a full year in September 1911, with the men returning, sporadically, to their individual collieries on worse terms than before. Troops slowly diminished in number but remained present to the end. Churchill had offended the owners by his early vacillation and his scarcely complimentary feelings about them, but he had also effectively ended any possibility of success for the strategy and tactics adopted by the Cambrian Combine strike committee. It may well be that his inclination to bellicosity in future industrial relations disputes—in July 1911 he threatened to put 25,000 troops into London to do the work of striking dockers and as a Conservative minister during the General Strike of 1926 was an ardent advocate of troop deployment—was more than enough to cement his reputation as a foe of organised labour. Yet it was, decidedly and decisively, from Tonypandy in 1910 that the judgement against him was lodged and from where, in 1912, the syndicalist Noah Ablett would remind “you men of Tonypandy” of what happened when the state allegedly held the ring.

Long Legacy

Tonypandy was a cusp moment. After the defeat, the ground shifted in ways unexpected in their rapidity and profundity before the strike. In 1912 a form of the minimum wage was won by a nation-wide coal strike. In 1912 William Abraham (Mabon) resigned as SWMF President. The Executive Council of the SWMF welcomed the “advanced men” into its ranks. The days of Lib-Labism were at an end. Labour representation on the council in the Rhondda and as parliamentary seats increased exponentially and was fixed for generations across South Wales from the 1920s. Will John, a pre-eminent leader imprisoned in the strike, replaced Mabon as Rhondda West’s MP (until 1955), and in 1933 W. H. Mainwaring, an author of The Miners’ Next Step, became Labour MP for Rhondda East (until 1959). Arthur Horner, elected from prison to be the miners’ leader in Maerdy, Rhondda in 1919, wrote:

I walked over the mountains… through the night to Tonypandy in November 1910 when we heard that Winston Churchill had called out the troops against the miners… to reinforce the thousands of police already in the area…[and create a] vicious alliance of the Government and the coal owners, against miners who asked no more than a wage little over starvation level. I never forgot that lesson.

In 1936 Horner became Communist President of the SWMF and in 1946 was elected from South Wales as the General Secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers. The coal industry was nationalised by the Labour Government in 1947. The following year, the National Health Service, prefigured by numerous Medical Aid schemes in the coalfield, was ushered in by another former miner fromSouth Wales, Aneurin Bevan from Tredegar. “Squalid nuisance” was Churchill’s jibe at Bevan (see p. 31), but more significantly the metropolitan press christened him, with more essential truth than geographic accuracy, the “Tito from Tonypandy.”

It was what had transpired in so many such ways since 1910 that caused Tonypandy to haunt the career of Winston Churchill in 1950. It was why Tonypandy, allied to his name, caused Clement Attlee, in a private Labour Party meeting in 1940, to wonder whether a Labour presence in a Churchillled government was even possible. Tonypandy proved to be Churchill’s albatross, as much a social and cultural one as it was in any formal political sense, because of all that it represented as a legitimate protest against unyielding overlordship and for what it laid bare of the reality of power relationships. If there is a one-word answer to the question why the great and victorious war leader suffered his post-war electoral defeats, first in 1945 and again in 1950, then that word is “Tonypandy,” and not so much by then for what had happened, in confusion in 1910, as for what it signified with devastating clarity across Great Britain.

Sources and Further Reading

Winston Churchill steadfastly snubbed all proposals for a Parliamentary Enquiry into his action during the 1910–11 Cambrian Coal Strike. His apparent insouciance has been echoed by his numerous biographers, who serially treat the matter of “Tonypandy” in either a perfunctory or dismissive manner. In part, this may be because the primary published documentation we have, and from which the telegrams and messages cited in this essay derive, establish his genuine uncertainty and ambivalence at the time of his original decision making. The document is Colliery Strike Disturbances in South Wales: Correspondence and Report, November 1910, Parliamentary Papers, 1911 (5568). Churchill’s equally genuine concern and puzzlement, however, over his being endlessly coupled with this “minor” incident, even as he became a major political force and a world historical figure, is plain to see from the role “Tonypandy” played in 1949 and 1950 as he tried, unavailingly, to kick it away (appropriately enough in a soccer stadium). See, for example, the Western Mail for January 1949 and February 1950.

Historical accounts as to the sending (or not) of troops to Tonypandy are relatively straightforward and longstanding, despite an almost perennial howl of indignation in the Letter Pages of newspapers whenever the “cruel lie” (that he did) surfaces. I have addressed the issue again, definitively I hope, herein, but my central assertion is two-fold: first, that the tangential riot of destruction in the township is indicative of fault lines in the society of Edwardian and Liberal Wales, little understood at the time, heralding the passing away within a decade of the Wales of his friend, David Lloyd George; secondly, that the Cambrian Coal Strike and its directly associated riotous clashes were, however, the focal issue which brought about the importation of troops and Metropolitan Police, thereby exposing the myth of State neutrality asserted by Churchill. It would, thereafter, be the Wales of Aneurin Bevan, Churchill’s profoundest opponent, which would eventually be ushered in as the roots of social democracy were nurtured and developed to branch out in a postwar Britain. Their apogee would be the 1945 Labour Government. The association of Tonypandy with that widespread change in both dream and deed is clear.

I set out chapter and verse, along with a an array of other footnoted material, for these conjoined matters in my article “Tonypandy 1910: Definitions of Community” (Past and Present, May 1980, Number 87) and expounded further in both my Aneurin Bevan and the World of South Wales (University of Wales Press, 1993) and my In the Frame: Memory and Society in Wales, 1910–2010 (Parthian, 2010). More recently, Daryl Leeworthy drew connected threads together in his brilliant essay “Tonypandy 1910: The Foundations of Welsh Social Democracy” in Secular Martyrdom in Britain and Ireland (eds., Outram and Laybourn, 2017). Finally, on the streets of Tonypandy in 2010, there were memorial celebrations and parades, whilst school projects were undertaken so that the “long memory” might endure A splendidly produced book of contemporary photographs and documented evidence with expert commentary was published by Gwyn Evans and David Maddox, two former Tonypandy schoolteachers, with the title The Tonypandy Riots, 1910–11 (University of Plymouth Press, 2010), and therein you can see the mounted Hussars on the roads of the Rhondda Valley and the faces of those who proved, against all the odds, to be the nemesis of Winston Churchill.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.