Finest Hour 184

“Young, Gleaming Champion” Elizabeth II

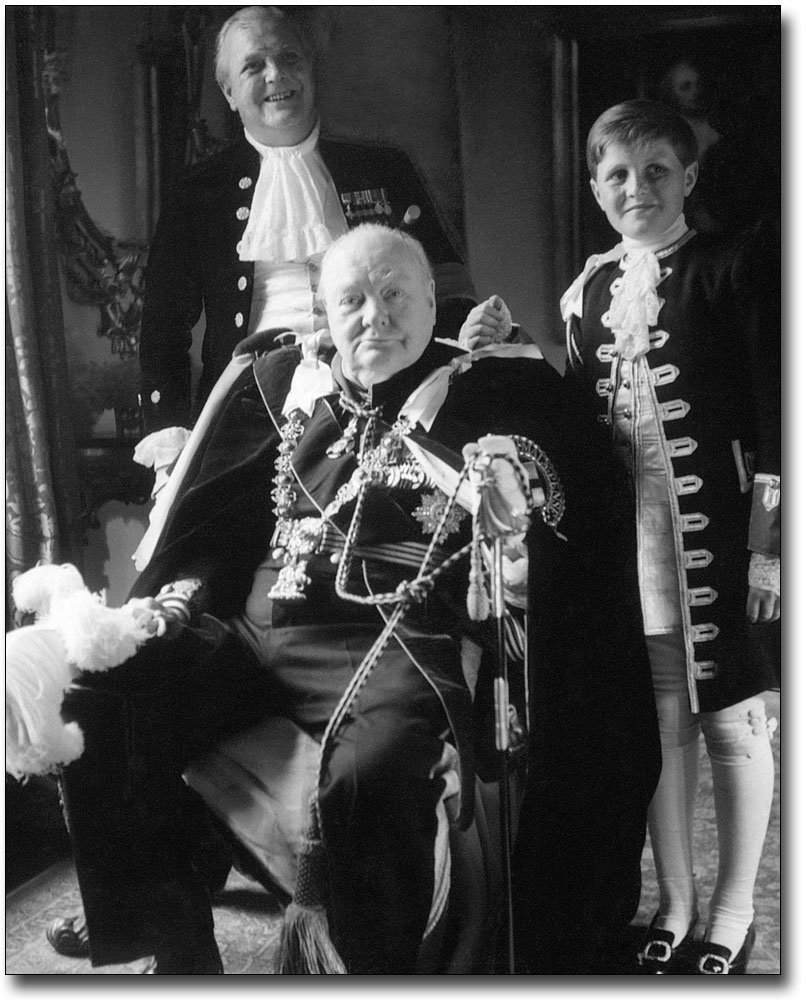

Queen Elizabeth II (second from left) following Churchill's funeral, 30 January 1965

June 26, 2019

Finest Hour 184, Second Quarter 2019

Page 34

By Ronald I. Cohen

Ronald I. Cohen MBE is author of A Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill, 3 vols. (2006).

As this issue of Finest Hour makes clear, Winston Churchill served under six monarchs. His extraordinary tenure of sixty-two years and thirty days as an MP began when he was elected during the reign of a monarch who came to the throne in 1837 and ended with a queen who still graces the throne today, 182 years later. And Queen Elizabeth II herself became the longest-reigning British monarch on 9 September 2015, when she surpassed her great-great grandmother, Victoria, who had served for sixty-three years and 216 days.

Churchill was fifty-one years old when Princess Elizabeth was born on 21 April 1926. When they first “met,” just over ninety years ago, in September 1928, Churchill, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, was visiting Balmoral as Minister in Attendance on King George V. The only other guest at the Royal Family’s Scottish estate that day was Princess Elizabeth of York, then aged two. With no expectation that their futures would become entwined, Churchill wrote to Clementine, who had not accompanied him, “[The Princess] has an air of authority and reflectiveness astonishing in an infant.”1

The King’s eldest son, the Prince of Wales, was then a youthful thirty-four, and there was little prospect that Churchill’s relationship with the eldest daughter of the King’s second son, the Duke of York, would deepen.

Heir Presumptive

How quickly things changed. Eight years later, the Prince of Wales, who had become King Edward VIII on the death of his father in January 1936, abdicated in December of the same year, and the Duke of York became King George VI. The Princess Elizabeth thus became the heir presumptive. Despite the change, not much significant interaction between Churchill and Elizabeth ensued. There was, of course, the incidental contact that flowed from Churchill’s deep relationship with Elizabeth’s father, and she was, and remained ever after, very conscious of the growing intimacy and mutual respect between the PM and the King.

Following the War, a very personal bond developed between Elizabeth and Churchill. In the spring of 1947, Jock Colville, who had served as Churchill’s Assistant Private Secretary during the war, was invited to become Private Secretary to Princess Elizabeth. Colville agreed, “spurred on by Winston Churchill who pronounced: ‘It is your duty to accept.’ It was in the event a greater pleasure than a duty, for I served a young lady as wise as she was attractive.”2

In another example of the developing warmth between them, on learning of the betrothal of Princess Elizabeth to Philip Mountbatten in early July 1947, Churchill sent a congratulatory letter to the King, to which the Princess herself sent a handwritten note: “I write to send you my sincere thanks for your kind letter of congratulations on my engagement, which has touched me deeply.” She added that she appreciated that Churchill had been “one of the first who have sent their good wishes.”3

Three months later, Churchill made it his business to drive to London to second the Address of Congratulations on the forthcoming royal marriage. Then, a month later, Churchill and Clementine attended the wedding at Westminster Abbey. In due course, attentive to her as always, Churchill sent good wishes to Princess Elizabeth on the first birthday of Prince Charles, on 14 November 1949, and she sent a telegram of thanks the following day.

On a purely personal level, Churchill and Princess Elizabeth also had a mutual interest in horse racing. In May 1951, the Princess invited Churchill to luncheon with her at Hurst Park racecourse prior to the Winston Churchill Stakes. The pressure was on since they had competitive horses in the running. Churchill’s was Colonist II; Elizabeth’s was Above Board. In the result, Colonist II won, followed closely by Above Board. Churchill wrote the Princess a week later, saying, among other things, and probably genuinely: “I wish indeed that we could both have been victorious—but that would have been no foundation for the excitements and liveliness of the Turf.”4 In June 1951, rather coincidentally, the horse she rode when she stood in for her father at the Trooping the Colour was named Winston.

When in September 1951, the King underwent surgery to remove his left lung, Churchill, then Leader of the Opposition, expressed his concern about Elizabeth and Prince Philip flying to Canada and the United States given the precarious state of the King’s health. Nonetheless, they did make the trip, and the King survived the surgery. By the time the royal couple returned from North America on 19 November, Churchill was able to welcome them back as the newly restored Prime Minister. He said: “Madam, the whole nation is grateful to you for what you have done for us and to Providence for having endowed you with the gifts and personality which are not only precious to the British Commonwealth and Empire and its island home, but will play their part in cheering and in mellowing the forward march of human society all the world over.”5

Given the Princess’s important position as heir presumptive, and the growing illness of the King, her royal responsibilities grew, and the Churchill relationship deepened.6 The dreaded but inevitable day occurred when the King died on 6 February 1952. The Princess, suddenly the new Queen, was at that moment again on the road, having left on 31 January for Kenya. Staying in the legendary, but remote— and now destroyed—treehouse at the Treetops Hotel to get closer to wildlife, she was delayed in learning of her father’s overnight death.

Queen Elizabeth II

Churchill called a meeting of the Cabinet for 11:30 that morning to inform them of “the grievous news.” The shock of the death of the King, his close companion during the War, dealt Churchill a severe blow. Jock Colville wrote, “When I went to the Prime Minister’s bedroom he was sitting alone with tears in his eyes, looking straight in front of him and reading neither his official papers nor the newspapers. I had not realized how much the King meant to him.” Oddly, when Colville “tried to cheer him up by saying how well he would get on with the new Queen,…all he could say was that he did not know her and that she was only a child.”7

Churchill’s grief did not end there. On the drive to London Airport to welcome the Queen back to Britain, his secretary Jane Portal later recalled, “He took me down in the car. He was going to broadcast that afternoon. On the way down, he dictated. He was in a flood of tears.”8 And yet, with that very brief bit of time between the King’s death and Churchill’s broadcast on the BBC, he composed one of the great eulogies of his career: beautiful, emotional, respectful, deeply caring, balanced and splendidly crafted.

In his remarks, the Prime Minister added anticipatory words about the new Queen. In these, we can sense his view of his sixth monarch: “Famous have been the reigns of our queens. Some of the greatest periods in our history have unfolded under their sceptre. Now that we have the second Queen Elizabeth, also ascending the Throne in her twenty-sixth year, our thoughts are carried back nearly four hundred years to the magnificent figure who presided over and, in many ways, embodied and inspired the grandeur and genius of the Elizabethan Age. Queen Elizabeth the Second, like her predecessor, did not pass her childhood in any certain expectation of the Crown. But already we know her well, and we understand why her gifts, and those of her husband, the Duke of Edinburgh, have stirred the only part of the Commonwealth she has yet been able to visit.”9

Indeed, it was this moment that marks the crossing of the divide in the Churchill-Elizabeth relationship. While she was his sixth sovereign, he was her first Prime Minister, and one cannot avoid noting the father image he would have represented for the young Queen, twenty-five years old at that moment, while he was seventy-seven, and twenty-five years older than her own father.

As much as he had admired Princess Elizabeth, it is fair to observe that, once she became Queen, and he her mentor, their relationship became mutually reverential, although it did ultimately and undeniably evolve into a more asymmetric relationship as her confidence grew. Colville explained Churchill’s attitude thus: “There was one lady by whom, from 1952 onward, Churchill was dazzled. That was the new Queen.”10 He added, “Here then was a woman whom he respected and admired more than any man.” In the early days of her reign, Colville noted that “A photograph of the Queen, smiling radiantly on her way to open her first Parliament, was framed and hung on the wall above his [Churchill’s] bed at Chartwell.” The photograph shows the Queen smiling and radiant, dressed in white, and wearing long white gloves. Gazing at the image, Churchill said to Lord Moran, his doctor: “Lovely, she’s a pet. I fear they may ask her to do too much. She’s doing so well.” And later that month, admiring the same photograph, Churchill said, “Lovely, inspiring. All the film people in the world, if they had scoured the globe, could not have found anyone so suited to the part.”11

Roy Jenkins described the relationship as follows: “He [Churchill] was imbued with romantic feelings both for the beginning of a new Elizabethan age and for the person of his new Sovereign.” He also referred to Churchill’s “respect for the institution of monarchy and near idolatry of the person of the just-crowned Queen.”12 And Churchill’s last Private Secretary, Anthony Montague Browne, said of their relationship, “WSC’s position is very easily summarised: he was the staunchest Royalist and he adored the Queen.”13

Working Relationship

While we do not, of course, have details regarding the substantive nature of the discussions that took place at the weekly Audiences between the Queen and her first Prime Minister, there is evidence of the warmth and collaborative nature of their relationship. Of the nature and tone of their meetings, Colville observed that Churchill’s “audiences had been dragg[ing] out longer and longer as the months went by and very often took an hour and a half, at which I may say racing was not the only topic discussed.” In general, the Queen’s Private Secretary Sir Alan “Tommy” Lascelles remained in an ante-room unable to hear the conversation but often catching peals of laughter. As he wrote in his diary, “Winston generally came out wiping his eyes. ‘She’s en grande beauté ce soir,’ he said one evening in his schoolboy French.”14

In terms of the balance of the relationship as time moved on, Montague Browne observed: “Certainly his relations with the Queen did not reach the level of comradeship they had attained with George VI. Given the difference of age they could hardly do so, but I did sometimes feel that the level of regard and affection was somewhat one-sided, although WSC was always treated with the greatest respect.”15

Indeed, the Queen offered Churchill membership in the Most Noble Order of the Garter, an honour that Churchill had refused from George VI after the War following his loss in the General Election. He famously said, “How can I accept the Order of the Garter when the people of England have just given me the Order of the Boot?” On this occasion, almost seven years later and less than six weeks before the Coronation, he accepted.16 Of that great honour, he wrote to his old friend, Pamela Lytton, in response to her congratulatory letter to him: “I took it because it was the Queen’s wish. I think she is splendid.”17

Following the Coronation of Elizabeth on 2 June 1953, Sir Winston broadcast on the BBC. The heartfelt tone of his words on the “day which the oldest are proud to have lived to see and the youngest will remember all their lives” referred admiringly to the “lady whom we respect because she is our Queen and whom we love because she is herself. ‘Gracious’ and ‘noble’ are words familiar to us all in courtly phrasing. Tonight they have a new ring in them because we know they are true about the gleaming figure whom Providence has brought to us.”18

One matter discussed by Churchill and the Queen about which we do know something is the question of Churchill’s coming retirement. This was, of course, a matter of considerable interest to Anthony Eden and other members of the Conservative Party, but, as we also know, Churchill continually flirted with the idea of staying on.

In an audience with the Queen on 29 March 1955 (in an “I would like to stay a little longer” moment), Churchill apparently asked whether she had any objection to his postponing his resignation. As Colville later wrote, “he thought of putting off his resignation. He had asked her if she minded and she said no!”19 While the Queen said she had none, Colville’s more cautious point of view prevailed, and Churchill determined that he had to leave. He asked Sir Michael Adeane, the Queen’s Private Secretary, to inform the Queen of his intended resignation as Prime Minister. Adeane, having conferred with Her Majesty, conveyed her reaction hours later: “She added that I must tell you that though she recognized your wisdom in taking the decision which you had, she felt the greatest personal regrets and that she would especially miss the weekly audiences which she has found so instructive and, if one can say so of State matters, so entertaining.”20

The date was fixed: 6 April 1955. A final dinner at Number 10 was proposed for 4 April. An excerpt from Churchill’s parting words to the Queen, delivered at that small private dinner, gives a sense of the deep devotion to her that he felt: “Never have the august duties wh[ich] fall upon the British Monarchy been discharged with more devotion than in the brilliant opening of Your Majesty’s reign. We thank God for the gifts He has bestowed upon us and vow ourselves anew to the sacred causes and wise and kindly way of life of wh[ich] Your Majesty is the young, gleaming champion.”21

Following his resignation, Churchill left on a much-deserved, and likely much-needed, holiday in Sicily. As he boarded the plane, he was handed a holograph letter from the Queen, in which she wrote in part: “In thanking you for what you have done, I must confine myself to my own experience, to the comparatively short time—barely more than three years—during which I have been on the throne and you have been my First Minister. If I do not mention the years before and all their momentous events, in which you took a leading part, it is because you know already of the high value my father set on your achievements, and you are aware that he joined his people and the peoples of the whole free world in acknowledging a debt of deep and sincere thankfulness.”22

Churchill of course replied, saying in part, and therein emphasizing his attitude toward his sixth sovereign, that “the whole structure of our new-formed Commonwealth has been linked and illuminated by a sparkling presence at its summit.”23

Last Respects

There was one more potential honour to consider for Churchill. It had become customary for departing Prime Ministers to accept earldoms if they wished to sit in the House of Lords (as Stanley Baldwin and Clement Attlee had done before Churchill’s departure, and Anthony Eden, Harold Macmillan, and Harold Wilson all did after). But surely Sir Winston Churchill merited greater recognition than an earldom? When Colville suggested to Buckingham Palace that a dukedom would be a more deserved reward, he was told, “that no more dukedoms would ever be given except to Royal personages.” The gesture of making the offer, however, did seem appropriate, provided Colville “could give the undertaking that the Prime Minister would refuse it.”24

Politics at the Palace? Indeed. Once she received the assurance that Churchill would refuse the offer of a dukedom, the Queen felt comfortable in extending it. It turned out to be a closer thing than she expected. When she proffered the dukedom, Churchill admitted afterwards that he was so taken by the Queen’s beauty, charm, and kindness that for a moment he thought of accepting. But then he remembered himself and begged to be allowed to decline. “And do you know,” Churchill said to Colville, “it’s an odd thing, but she seemed almost relieved.”25

The emotional closeness of their relationship is again revealed in the last meaningful written exchange they shared. In January 1962, after ten years of the Queen’s reign, and three years before Churchill’s own death, he wrote:

Madam,

At the conclusion of the first decade of your Reign, I would like to express to Your Majesty my fervent hopes and wishes for many happy years to come. It is with pride that I recall that I was your Prime Minister at the inception of these ten years of devoted service to our country.

The very next day the Queen replied,

My dear Sir Winston,

I was most touched to receive your letter of good wishes on the tenth anniversary of my succession.

I shall always count myself fortunate that you were my Prime Minister at the beginning of my reign, and that I was able to receive the wise counsel and also friendship which I know my father valued so very much as well.26

Following Churchill’s stroke in 1953, “Operation Hope Not” had been conceived and driven forward by the Queen, who had determined that Churchill should be accorded a state funeral on a scale befitting his position in history. According to Churchill’s daughter Mary, the Queen had indicated that intention to her father several years before he died, and he had been very gratified at the sovereign’s expressed wish. Details of the planning of the state funeral began to be made in 1958 under the guidance of the Duke of Norfolk, and a formal Committee was formed in 1963. Some of the plans had to be rewritten over time owing to the fact that Churchill, according to Lord Mountbatten, kept living and the pallbearers kept dying. The final document, completed in November 1964, was 200 pages long.

On 24 January 1965, seventy years to the day following the death of Lord Randolph Churchill, Sir Winston died. The following afternoon, it was announced by the Lord Privy Seal, that a message had been received from the Queen: “Confident in the support of Parliament for the due acknowledgement of our debt of gratitude and in thanksgiving for the life and example of a national hero, I have directed that Sir Winston’s body shall lie in State in Westminster Hall and that thereafter the funeral service shall be held in the Cathedral Church of St Paul.”27

At the funeral service, the “vast congregation was headed by the Queen who—waiving all custom and precedence—awaited the arrival of her greatest subject.”28

The culmination of the relationship, its warmth, and the great respect for her first Prime Minister is also evidenced by the inscription the Queen added to the wreath of white flowers she provided at the funeral service. Written in her own hand, it read:

“From the Nation and the Commonwealth. In grateful remembrance. Elizabeth R.”29

Endnotes

1. Letter of 25 September 1928 from Balmoral, Mary Soames, ed., Speaking for Themselves: The Personal Letters of Winston and Clementine Churchill (London: Doubleday, 1998), p. 328.

2. John R. Colville, The Fringes of Power (New York: Norton, 1986), p. 718.

3. Emphasis added. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, volume VIII, Never Despair, 1945–1965 (London: Heinemann, 1988), pp. 340–41.

4. Letter of 20 May 1951, ibid., p. 613, and in Fred Glueckstein, “Winston Churchill and Colonist II,” Finest Hour 125 (Winter 2004–05), p. 28.

5. Gilbert, Never Despair, pp. 662–63.

6. Elizabeth was never created Princess of Wales because George VI opposed the designation. See Colville, Fringes, p. 468 and n. 2.

7. Ibid., p. 640.

8. Gilbert, Never Despair, p. 697.

9. Robert Rhodes James, ed., Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches, volume VIII, 1950–1963 (New York: Chelsea House, 1974), p. 8338.

10. John R. Colville, Winston Churchill and His Inner Circle (New York: Wyndham Books, 1981), pp. 155–57.

11. Charles Wilson, Churchill: Taken from the Diaries of Lord Moran: The Struggle for Survival 1940–1945 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966), p. 425 and p. 429.

12. Roy Jenkins, Churchill: A Biography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001), p. 860.

13. Anthony Montague Browne, Long Sunset: Memoirs of Winston Churchill’s Last Private Secretary (London: Cassell, 1995), p. 173.

14. Quoted in Sally Bedell Smith, Elizabeth the Queen: The Life of a Modern Monarch (New York: Random House, 2012), p. 93.

15. Montague Browne, Long Sunset, p. 173.

16. It should not be forgotten that Lady Soames was herself admitted to the Order of the Garter in 2005.

17. Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (London: Heinemann, 1991), p. 911.

18. In addition to its inclusion in Robert Rhodes James’s Complete Speeches (New York: Chelsea House, 1974), the brief text of the broadcast was separately published in a charming and scarce miniature book, The Queen’s Message Broadcast on Coronation Day, 2 June 1953, by the Hand & Flower Press at Aldington.

19. Colville, Fringes, pp. 708–09.

20. Emphasis added. Gilbert, A Life, p. 939.

21. Emphasis added. Gilbert, Never Despair, pp. 1120–21.

22. Gilbert, A Life, p. 940.

23. Ibid.

24. Gilbert, Never Despair, pp. 1123.

25. Ibid., p. 1124.

26. Gilbert, Never Despair, p. 1333.

27. Ibid., pp. 1360–61.

28. Mary Soames, A Churchill Family Album (London: Allen Lane, 1982), captions 415–16.

29. Gilbert, Never Despair, p. 1364, and in The Times of 31 January 1965.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.