Finest Hour 184

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – Twin Titans

June 19, 2019

Finest Hour 184, Second Quarter 2019

Page 45

Review by Mark Klobas

Mark Klobas teaches history at Scottsdale College and hosts a podcast for the New Books Network.

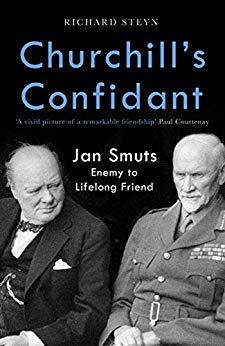

Richard Steyn, Churchill’s Confidant: Jan Smuts, Enemy to Lifelong Friend, Robinson, 2018, 224 pages, £25/$45. ISBN 978–1472140760

He was a man of formidable intelligence who, over the course of his long life, proved himself to be a patriot and an apostle for the civilizing mission of the British Empire. As a young man he made his reputation in the Boer War with a daring episode of defiance in the face of the enemy. A rising politician who served in several offices in the years leading up to the First World War, during the conflict he served with distinction both in uniform and out. After several years in the political wilderness, he returned to office at the start of the Second World War and as prime minister led his country to victory, only to be ignominiously turned out of office in its aftermath.

While many readers will discern in the previous paragraph the outline of Winston Churchill’s biography, it serves just as effectively as a summary of Jan Smuts’s equally extraordinary life and career. Yet Richard Steyn begins his study of the relationship between the two men by focusing instead on their differences, which were just as numerous as their similarities. As an adult Smuts lived an austere life that stood in stark contrast with Churchill’s love of luxury. To a degree this reflected the difference in their upbringing: whereas Churchill was born to one of the most illustrious families in Britain, Smuts’s parents were prosperous but otherwise undistinguished farmers. While Churchill proved an indifferent student, Smuts excelled academically, graduating with double first-class honors in South Africa and from Cambridge University before returning to the Cape Colony to work as an attorney. Though both were drawn to politics, initially it served as a point of division between them. In the aftermath of the 1895–96 Jameson Raid, a disillusioned Smuts renounced his early praise for Cecil Rhodes and moved to the Transvaal, where he became the state attorney in Pretoria. It was in this capacity that he first encountered Churchill in Lady- smith after the latter’s capture as a prisoner of war in October 1899, though more than six years would pass before the two met formally.

2025 International Churchill Conference

The cornerstone of a lifelong friendship was laid in January 1906, when Smuts traveled to London to lobby the new Liberal administration for self-government for the Transvaal. As the newly installed Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, Churchill played a major role in the settlement process that resulted in the creation of the Union of South Africa. In the years that followed, the two men’s careers often intersected, including their mutual service in Lloyd George’s government during the First World War and Churchill’s postwar stint as Colonial Secretary. Steyn describes how each influenced the other’s career at these points, but it was not until the Second World War that the two men truly worked in partnership toward pursuit of a common goal. This six-year period takes up nearly half of Steyn’s book, as he describes the numerous challenges the two prime ministers surmounted in pursuit of victory. Here Smuts’s political difficulties stand out, for he faced sharp divisions at home over South Africa’s participation in the war. While Smuts ultimately overcame this dissent, his problems were not helped by involvement in Allied and imperial war councils, which often necessitated extended trips abroad. Yet Steyn makes clear how much Churchill valued Smuts’s counsel, to the extent that he even proposed the South African as his most capable replacement should he himself become incapacitated, even though he knew such an idea was impossible politically.

An examination of the relationship between Churchill and Smuts offers a look at the interaction of two of the greatest international statesmen of their age and how in working together they helped shape their times. Unfortunately, this is not what Steyn provides in this book. For the most part what he offers is mainly a summary of Churchill’s life written from the perspective of the author’s comfort zone as a Smuts biographer. There is nothing in the way of original research and analysis, with even the published papers of the two men used only sparingly. Instead Steyn relies primarily upon a handful of biographies, most of which in the case of Churchill likely reside already on the shelves of most aficionados of the man. While readers seeking the basics about the lives of Churchill and Smuts might profit from reading this book, it falls well short of the penetrating examination the subject deserves.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.