Finest Hour 184

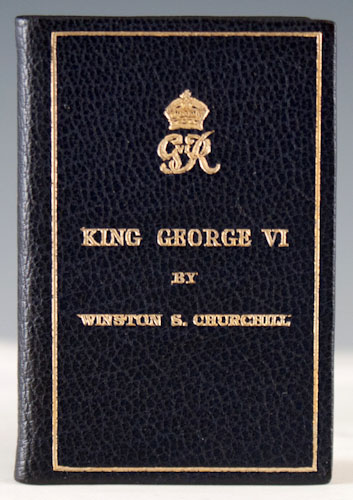

The Dutiful King: George VI

Coronation Day, 12 May 1937

July 3, 2019

Finest Hour 184, Second Quarter 2019

Page 29

By Hugo Vickers

Hugo Vickers is a writer and broadcaster who has written biographies of many twentieth-century figures, including Elizabeth, The Queen Mother (2005). His biography of Gladys Deacon, the second wife of Churchill’s cousin the ninth Duke of Marlborough, will be reissued in 2020.

King George VI died on 6 February 1952, and it fell to Edward Ford, the King’s Assistant Private Secretary, to break the news to Winston Churchill at 10 Downing Street. “Bad news, the worst,” he said, laying aside his papers and descending into considerable gloom. A few days later at the funeral, Churchill’s wreath bore the simple words: “For Valour.” By the time of his death, the King had earned the highest respect and admiration from his Prime Minister. On this the historians agree. Andrew Roberts, Churchill’s latest biographer, wrote that during the war the King and Churchill formed a bond “that was eventually to become as strong as any Churchill enjoyed in public life.”1 Sir John Wheeler-Bennett, George VI’s official biographer, cited Churchill as “the man with whom he was to work in later years in such close accord for the salvation of their country.”2

It was not ever thus.

Churchill became the King’s Prime Minister in 1940. At first the relationship was uneasy. The King and Queen Elizabeth were aware of the combative stand that Churchill had taken in regard to Edward VIII, urging him to fight his corner in the Abdication crisis. George VI and Elizabeth were appeasers by inclination. They were close friends of Lord Halifax, another contender for the post. None of this warmed them towards this rumbustious figure who took over the reins of power in wartime. Sir Alec Hardinge, then the King’s Private Secretary, described Halifax as “always the court favourite,” noting, “It took me a long time to get the King and Queen to look on the new Prime Minister with favour, but in the end the King at any rate made great friends with him.”3

2025 International Churchill Conference

A shared interest in the Royal Navy created at least a superficial bond of interest. On this they were able to build. As Prince Albert, George VI had first met Churchill in 1912 when the latter, as First Lord of the Admiralty, came aboard the Royal Yacht Victoria and Albert to greet King George V.

At the time of George VI’s Coronation in 1937, Churchill had made a stab at a loyal gesture, pointing out that he had served George VI’s grandfather, father, and brother “for very many years” and wished him a reign “blessed by Providence” adding “new strength and lustre to our ancient Monarchy.”4 By then Churchill had become somewhat disenchanted with the Duke of Windsor, the former King Edward VIII, who was causing trouble after the abdication. Churchill told his wife, Clementine: “I now realise that the other one wouldn’t have done.”5 King George VI’s reply, written in his own hand, thanked Churchill for his “very nice letter,” appreciated “how devoted” Churchill had been and still was to his “dear brother,” and thanked him for his “sympathy and understanding in the very difficult problems that have arisen since he left us in December.” The new King added that he fully realised “the great responsibilities and cares” that had now fallen upon him.6

Different Men

Churchill and the King could hardly have been two more different men. George VI was a modest, shy, and retiring man, who had been propelled unexpectedly onto the throne in December 1936. He had had no idea that this was to be his fate until a few weeks before, when it became clear that Edward VIII was resolute on marrying Wallis Simpson and prepared to depart. George VI took on what Sir Alan Lascelles called “the most difficult job in the world” without the training and expectations of his elder brother.7 He and Queen Elizabeth were not at all sure that the British public would want them, though, as it soon transpired, the nation preferred the image of their quiet family life—Sunday lunch, a walk in the park, a cup of tea—to the brittle and unappealing cocktail-shaker and nightclub world of Edward and Mrs. Simpson. And George VI did indeed possess what the Duke of Windsor described as that “one matchless blessing, enjoyed by so many of you and not bestowed on me—a happy home with his wife and children.”8 Queen Elizabeth was strong, with a moral backbone like a rod of iron. Though she would have strenuously denied being the power behind the throne, that is what she was. The new King only wanted to be a good constitutional monarch, and her support of him made this possible.

Churchill, by contrast, was considered by many to be a warmongering figure. He had been, as Wheeler-Bennett put it, “uninhibited by slavish loyalty to any one party, unencumbered by over-long devotion to outworn political shibboleths.”9 He had crossed the Chamber of the House of Commons. Was he a Liberal, a Constitutionalist, or a Conservative? He was full of oratory and bluster, a very different man from the King. He followed his instinct, often to his own advantage.

George VI had felt comfortable with Neville Chamberlain. He had been disappointed not to get Lord Halifax as the Prime Minister’s successor. Wheeler-Bennett suggested that it was not surprising if the King felt “somewhat overwhelmed by the very magnitude of Mr. Churchill’s personality.”10

To Canadian Prime Minister W. L. Mackenzie King, George VI said that “He would never wish to appoint Churchill to any office unless it was absolutely necessary in time of war.”11 By the time that Churchill entered the cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty in September 1939, he was invariably referring to George VI as “our noble King.”12 Nevertheless, His Majesty did not find Churchill easy to work with at first, noting: “Winston is difficult to talk to, but in time I shall get the right technique I hope.”13

No Better Prime Minister

Churchill became Prime Minister in May 1940. It did not take the King long to appreciate his good fortune in having him as his wartime Prime Minister. George VI soon realised that Churchill was a man of stature as well as a certain charm, and such was the gravity of danger to Britain and the Commonwealth that the two were soon thrown together in mutual collaboration. In time this became one of friendship and mutual admiration. The King began to look forward to Churchill coming for an Audience. Each was able to unburden his mind.

As early as 10 September 1940, these formal audiences had been replaced by informal Tuesday luncheons at which no staff were present, the King and his Prime Minister serving themselves from a side-table and able to talk freely about state business. Occasionally the Queen joined them. There were times when these luncheons were interrupted by air raids. The lunches continued for four and a half years, when both men were in London. Of these occasions Churchill later wrote: “I valued as a signal honour the gracious intimacy with which I, as first Minister, was treated, for which I suppose there has been no precedent since the days of Queen Anne and Marlborough during his years of power.”14

A feature of the growing relationship was that the King at last felt that he was genuinely useful. He and the Queen paid innumerable visits to different parts of Britain and so he was able to give Churchill first-hand accounts of the mood in the country.

Buckingham Palace was bombed twice within three days in September 1940, and altogether in the war some nine times. Churchill commented in January 1941: “I have been greatly cheered by our weekly luncheons in poor old bomb-shattered Buckingham Palace & to feel that in Yr. Majesty and the Queen there flames the spirit that will never be daunted by peril, not wearied by unrelenting toil.”15 By February 1941, King George VI was confident enough to write: “I could not have a better Prime Minister.”16

Troubled Waters

And so the relationship developed in a generally positive way. But it would be wrong to suggest that it was always harmonious. There were times when Churchill bulldozed his way through royal sensibilities. The King found that Churchill sometimes sent messages to the Nation that he felt should have come from him, while in 1942 Victor Cazalet noted “how Winston quite unconsciously has put [the King and Queen] in the background.”17

Then in May 1944 the King and Churchill cooked up the idea that they would both like to sail in one of the bombarding warships on D-Day. It took the King’s Private Secretary, Sir Alan Lascelles, to point out the dangers to the King. He dissuaded him by asking him to brief eighteen-year-old Princess Elizabeth as to whom she should appoint to serve as Prime Minister in the event of the deaths of both the head of state and the head of government. The King took the point and furthermore realised that the captain of the warship in which they would travel would be inhibited from taking a full part in the action for fear of losing his distinguished passengers.

The King then set about trying to dissuade Churchill, describing the trip as a joy ride. Churchill was not pleased and brushed aside suggestions that he might be killed. The King was prepared to go down to Portsmouth to command Churchill in person not to sail. Churchill was finally persuaded to drop the idea by a sharp telephone call from Lascelles. But he was cross, complaining to the King about the unnecessary curbs placed on what he called “my freedom of movement when I judge it necessary to acquaint myself with conditions in the various theatres of war.”18 The King’s conclusion was: “I asked him as a friend not to endanger his life & so put me & everybody else in a difficult position.”19

Another area of disagreement involved the King’s wish to visit his troops in India in February 1945. Churchill felt that the political implications made this undesirable. This time the King was not pleased, though he suggested that the reason was entirely competitive. Had he gone, he would have been able to wear the Burma Star (medal), while Churchill would not.

Royal Friendship

Queen Elizabeth also helped the relationship. On one occasion she wrote out in her own hand a poem written in Napoleonic times and had it delivered to Downing Street, one line of which read, “the bad have finally earned a victory o’er the weak, the vacillating, inconsistent good.” This boosted Churchill’s morale.

The King held the Order of the Garter in the highest esteem and had negotiated with the Government that this would be in his personal gift, rather than a political appointment. He was so keen to bestow this on Churchill that he offered it to him three times. The first occasion was on 15 December 1944, whereupon Churchill became “all blubby,” but declined because the war was not yet won.20 The second occasion was on 23 May 1945 when Churchill resigned as Coalition Prime Minister. He declined on the grounds that there was a General Election pending. The third offer was made on 26 July 1945 when Churchill submitted his resignation after the Socialists won power. The King described this as “a very sad meeting” and told the outgoing Prime Minister that he thought the people “very ungrateful after the way they had been led in the war.”21 Queen Elizabeth II finally achieved her father’s wish by persuading Churchill to accept the Garter in 1953.

In September 1951, Churchill became deeply anxious about the King’s health and consulted his own doctor, Lord Moran, about the matter. Moran considered the various bulletins—the use of a bronchoscope implying cancer and the lack of reassurances. He explained this to Churchill. “The sense of history surrounding the throne of England and the mystery of death fanned the flame of his imagination,” wrote Moran. “The demise of the sovereign seemed to him like a revulsion of nature. He sat there, brooding darkly upon it.”22

On 26 October 1951, Churchill was returned as the King’s Prime Minister. The King was not well, but was able to receive him, pleased to have Churchill back again. But this was to be a short phase. On 6 February 1952, the King died in his sleep at Sandringham. On that day Churchill’s Private Secretary, Jock Colville, found Churchill with tears in his eyes: “I had not realized how much the King meant to him.”23

The Prime Minister spoke eloquently to the Nation: “During these last months, the King walked with death, as if death were a companion, an acquaintance, whom he recognized and did not fear. In the end death came as a friend, and after a happy day of sunshine and sport, and after ‘good night’ to those who loved him best, he fell asleep as every man or woman who strives to fear God and nothing else in the world may hope to do.”24

In the House of Commons he was more prosaic yet: “The late King lived through every minute of this struggle [World War II] with a heart that never quavered and a spirit undaunted; but I, who saw him so often, knew how keenly, with all his full knowledge and understanding of what was happening, he felt personally the ups and downs of this terrific struggle and how he longed to fight in it, arms in hand, himself.”25

A relationship between King and first minister, which had begun somewhat indifferently, ended on the highest possible note.

Endnotes

1. Andrew Roberts, Churchill: Walking with Destiny (London: Allen Lane, 2018), p. 467.

2. John W. Wheeler-Bennett, King George VI: His Life and Reign (London, Macmillan, 1958), p. 58.

3. Hardinge private notes, quoted in Dr. Peter Liddle et al., eds., The Great World War 1914–45, Volume 1 (New York: Harper Collins, 2000), p. 374.

4. Roberts, p. 413.

5. Robert Rhodes James, A Spirit Undaunted (Boston: Little Brown, 1998), p. 127.

6. Ibid., p. 128.

7. Duff Hart-Davis, ed., King’s Counsellor (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2006), p. 359.

8. Abdication speech, 11 December 1936, quoted in HRH The Duke of Windsor, A King’s Story (London: Cassell, 1951), p. 413.

9. Wheeler-Bennett, p. 445.

10. Ibid., p. 446.

11. Roberts, p. 453.

12. Ibid., p. 466.

13. Ibid., p. 475.

14. Liddle, p. 335.

15. Rhodes James, p. 165.

16. Wheeler-Bennett, p. 447.

17. Quoted in Sarah Bradford, King George VI (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1989), p. 340.

18. Quoted verbatim in the King’s diary, 2 June 1944, in Rhodes James, p. 259.

19. Rhodes James, p. 259.

20. Roberts, p. 851.

21. Roberts, p. 885.

22. Lord Moran, Winston S. Churchill, The Struggle for Survival, 1940–1965 (London: Constable, 1966), p. 341.

23. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, volume VIII, Never Despair, 1945–1965 (London: Heinemann, 1988), p. 696.

24. Ibid., p. 697.

25. Ibid., p. 699.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.