Finest Hour 180

A Regency Fit for a King: Churchill Visits Athens, December 1944

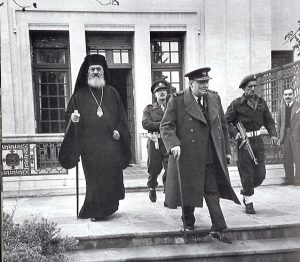

The Regent meets with his military chiefs of staff

August 24, 2018

Finest Hour 180, Spring 2018

Page 28

By Christos Bouris

Christos Bouris is a postgraduate student in the faculty of History and Archaeology at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

At Christmastime 1944, Winston Churchill travelled to Athens. It was a perilous journey, but the stakes were high: the future of Greece. Recently liberated from the Axis, Athens was now beset by confrontation between the communist-controlled EAMELAS (the first being a communist-led resistance group and the second her military counterpart) and British forces positioned in the Greek capital, assisted by Greek army units and security forces loyal to the Greek government. Both sides sought control of the city. The armed clash that ensued became known as “Dekemvriana” and ended with a British victory over the Greek communists.

Churchill arrived in Athens determined to use his influence in the negotiations between the Greek government and EAM in order to create a provisional government and avoid the outbreak of civil war. He also wanted to keep Greece free of communist control.

The Forces in Play

As early as 1943, when it was evident that the liberation of Greece from the Axis was imminent, clear differences emerged between the various Greek guerrilla forces fighting against the Germans and Italians. The main resistance groups were EAM-ELAS (which was the largest) and the right wing but mainly republican EDES. Both fought the common enemy but were also determined to consolidate their power and ensure that they would play a significant part in Greek politics after liberation. Another player was the Greek government in exile, which was essentially monarchist and in close relations with the British government, on whose support it was counting while it controlled the Greek military forces fighting in the Middle East and later in Italy.1

Gradually all the Greek resistance organizations were either eliminated or incorporated into EAM-ELAS and EDES, leaving only two factions with influence and power on Greek soil. Not satisfied with their respective areas of control, however, the two sides confronted each other militarily, beginning what is known as the “first round” of the Greek Civil War. Round One ended with the Lebanon agreement, the signatories of which included EAM-ELAS, EDES, and the Greek government in exile. This pact ensured the ending of hostilities between the two resistance groups and provided for the creation of a provisional government under George Papandreou, one fourth of whose cabinet would have to be composed of EAM-ELAS affiliates. Moreover, according to the armistice agreement signed on 20 May 1944, all the resistance groups would be subject to the control of the new government, as would the Greek armed forces in the Middle East; but this was not put into effect.2

Churchill was determined to support the Greek government and prevent the capture of Athens and Salonica by the communists. On 21 August 1944, he implemented operation “Manna,” which provided for the dispatch of a British military force of 10,000 men under Lieutenant General Ronald Scobie to Greece with the mission of securing and holding Athens and Salonica immediately after the withdrawal of German troops.3 Developments continued with the signing of the Caserta agreement in Italy between the Greek government and EAM on 26 September. This placed all the resistance units under the control of Scobie, while the communists accepted the arrival of British forces on Greek soil, agreed to keep ELAS out of Attica, and recognize Papandreou’s government as the EAM ministers took up their cabinet posts in Italy.4

The “Dekemvriana”

The Germans evacuated Athens on 12 October 1944. British troops occupied the city two days later, followed by the Greek government on the 18th. Reinforcements arrived in the form of elements of the 4th Indian Division and Greek army units from the Italian front. Control of Athens and its port Piraeus was then in the hands of the British and the Greek government forces, but the countryside was mainly controlled by ELAS. The Papandreou government remained in power due only to British support and not that of the Greek people and political parties.

Tension between the communists and the right wing simmered at every level of Greek society. One thorny problem was the reinstatement of Axis collaborators by the new government. Another was the sense that resistance fighters were being persecuted for their left-wing affiliations. Alongside these, the main issue was disbanding the resistance forces along with the royalist army units, which served the Greek government in exile, proceeding to the formation of a new national army. The will of the Greek government and General Scobie was to disband only ELAS and use exclusively royalist units as the basis for the new army.5 Scobie considered the royalists essential to support his own meager forces in Athens, but he insisted on disarming ELAS and pressed the Greek government to issue the order, which was published on 1 December.

The incident that triggered the outbreak of fighting was an EAM demonstration in Athens on 3 December, when Greek police opened fire killing several protesters. EAM-ELAS responded with an organized chain of attacks on police stations in the capital, prompting General Scobie to send his units against ELAS forces. The strength of the communist units was significant, amounting to around 12,000. This was more than Scobie expected and left British and Greek government forces in a difficult position until the arrival of large British reinforcements from Italy. During the fighting, the British used companies of a newly-created National Guard composed to a large extent of former members of the Security Battalions who had collaborated openly with the Germans during the Occupation.6

Our Man in Greece

From the beginning of the fighting, Churchill supported the decisions of General Scobie and the British ambassador in Athens, Sir Reginald Leeper, to suppress the revolt against the Greek government.7 Accordingly, the British Prime Minister resolved to intervene personally to resolve the conflict. In a dramatic decision, he flew to Athens along with Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and arrived there on Christmas day.

Churchill attempted to bring the different factions together and enable them to cooperate in finding common political ground so that peace and order would be restored. For this purpose, after much discussion with Leeper and the British Minister-resident at Allied Headquarters Mediterranean Harold Macmillan, Churchill formulated the plan of a conference consisting of representatives of the various Greek political parties, including EAM. To promote his design, Churchill met Prime Minister Papandreou and Archbishop of Greece Damaskinos, who would chair the conference. Macmillan states in his memoirs that the receipt of the invitations upset some of those invited, who resented the presence of EAM representatives, but these malcontents relented when the British threatened to reveal to the press the names of those who had refused the personal invitation of Churchill.8

GET OUR BULLETIN

Ultimately a conference was held comprising eminent figures from every political party, including three representatives of EAM-ELAS, along with high-ranking British political and military officials like Field Marshal Alexander. Churchill’s rationale behind sponsoring the conference was to put an end to the Greek conflict. He believed that the meetings would probably result in the formation of a united government and would show the world that Britain was determined to settle the Greek question.

In his opening speech, Churchill underlined his wish to end the Greek turmoil by political means, but at the same time he pointed out that—as a last resort—he was ready to resolve the issue militarily and indicated that he had the support of both Stalin and Roosevelt. After statements by Eden and Alexander, the British party departed, leaving the Greek politicians to their deliberations, which proved unfruitful.

The representatives of the establishment parties could not find common ground with EAM, whose representatives insisted that to sign an armistice they required control of half the cabinet seats and the complete disbanding of the troops supporting the government. Τhis provoked a strong negative response from the other politicians present. The only point on which almost all present could agree was the need to create a Regency, with Archbishop Damaskinos serving as Regent, while the return of George II, King of the Hellenes, to Athens would depend on the will of the Greek people, as expressed through a plebiscite.9

Regency by Fiat

On 26 December, the centrist newspaper Ελευθερία featured Churchill’s visit in its headline. The lead article suggested that the meeting he convened might resolve the turmoil.10 The next day’s headline referred to Churchill as the general representative of the Allies in Greece and analyzed the meeting and its results. The story mentions that during his speech Churchill expressed his will for Greece to be reinstated as a member of the United Nations through an agreement at the conference table and the creation of a provisional government. Additionally, he was reported to have stated that the British government was determined to enforce the rule of law in Greece and to clear the capital area of ELAS forces.11

On 28 December, the lead article in Ελευθερία once more reported on the conference and the fact that the participating representatives could not reach a general agreement beyond establishing a Regent in the place of the king, since the conditions for ending hostilities set by EAM were not acceptable to the other parties.12 More coverage was given to the Regency question following an extensive meeting on the 29th. The newspaper reported that on their return to England, Churchill and Eden would press George II to accept the decision of the conference and recognize Damaskinos as Regent until the Greek people could decide for themselves about the nature of the Greek polity.13

The decision to back the Archbishop as Regent was taken at the end of the second day of the conference when, after a private discussion with Damaskinos, the EAM delegates agreed to accept him. The communists had also asked to meet with Churchill privately, but he refused. The British Prime Minister was determined to do as he had threatened if the conference failed to arrive at a political solution: he would use military means to clear the Athens-Piraeus area of ELAS units. This he made clear in a telegram on 28 December sent to General Hastings Ismay in London.14 Churchill also did as he promised on his return to London and pressed the Greek king to accept Damaskinos as Regent by making it clear that the British government would recognize the Archbishop’s authority with or without the king’s support. This brought an immediate response from George II, who made a statement appointing Damaskinos as Regent.15

The opinion of the Greek communists about Churchill’s handling of the Greek question is found in a memorandum of May 1947 sent by the secretary general of the Greek Communist Party to Stalin. The Greek leader stated that, during the clash of December 1944, the British Prime Minister found Greece isolated and imposed his will, forcing EAM and the Greek Communist Party to accept an armistice early in 1945.16

What Was Achieved?

Churchill’s initiative to visit Athens and sponsor a conference of representatives from every main Greek party and political faction in order to stop the conflict that had broken out in and around the Greek capital did not result in a peaceful settlement. The Greek political establishment could not reach a compromise with the communist-led EAM-ELAS. Consequently, the clash continued between ELAS and the British forces in Attica, assisted by the regular Greek army units loyal to the Greek government and Greek security forces—some of whom had cooperated with the Germans.

Churchill’s intervention, however, did bring about general agreement of the parties represented at the conference for the appointment of a Regent until the Greek people could decide whether they wished to restore the monarchy. Without Churchill’s role and influence, it is highly unlikely that the Greek king would have accepted such an arrangement.

Endnotes

1. Charles Shrader, The Withered Vine: Logistics and the Communist Insurgency in Greece, 1945–49 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1999), pp. 23, 30–31.

2. Shrader, p. 35, and Baerentzen Lars and David Close, Η Ήττα του ΕΑΜ από τους Βρετανούς, 1944–5 [The Defeat of EAM by the British, 1944–5], in Ο Ελληνικός Εμφύλιος Πόλεμος 1943–1950. Μελέτες για την Πόλωση [The Greek Civil War 1943–1950. Studies in Polarization] (επιμέλεια: Close, David. ΑΘήνα: Φιλίστωρ, 1996), pp. 105–06.

3. Lars and Close, pp. 109–10.

4. Ibid., pp. 112–13.

5. Shrader, pp. 37–38; Lars and Close, p. 117; and Christopher Montague Woodhouse, Το Μήλο της Έριδος. Η Ελληνική Αντίσταση και η Πολιτική των Μεγάλων Δυνάμεων [Apple of Discord: A Survey of Recent Greek Politics in Their International Setting] (Αθήνα: Εξάντας, 1976), pp. 322–25.

6. Sharder, pp. 39–40 and Lars and Close, p. 123.

7. Woodhouse, p. 331.

8. Harold Macmillan, The Blast of War 1939–45 (New York: Harper and Row, 1968), pp. 520–21.

9. Winston S. Churchill, Triumph and Tragedy (London: Penguin, 2005), pp. 272–73; Woodhouse, pp. 334–35; Macmillan, pp. 522–26.

10. Ελευθερία (Πάνος Κόκκας), αρ. 93 (December 1944a).

11. Ελευθερία (Πάνος Κόκκας), αρ. 94 (December 1944b).

12. Ελευθερία (Πάνος Κόκκας), αρ. 95 (December 1944c).

13. Ελευθερία (Πάνος Κόκκας), αρ. 96 (December 1944d).

14. Churchill, pp. 276–77.

15. Ibid., pp. 278–79.

16. Φίλιππος Ηλιού, Ο Ελληνικός Εμφύλιος Πόλεμος. Η Εμπλοκή του ΚΚΕ [The Greek Civil War: The Involvement of the Greek Communist Party] (Αθήνα: Θεμέλιο, 2005), p. 93.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.