Finest Hour 180

Action This Day – Spring 1893, 1918, 1943

August 8, 2018

Finest Hour 180, Spring 2018

Page 40

By Michael McMenamin

125 Years ago

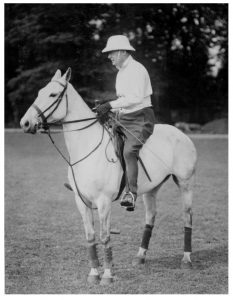

Spring 1893 • Age 18

“A Little Paternal Advice”

Winston spent the spring of 1893 “cramming” with Captain Walter James for the Sandhurst Entrance Examination scheduled for late June. Having twice failed the examination, Winston would have been expected to redouble his efforts, especially after Captain James had written to Lord Randolph in early March to say that Winston “means well but he is distinctly inclined to be inattentive and to think too much of his own abilities” and was “too much inclined up to the present to teach his instructors instead of endeavouring to learn from them.”

True to form, Winston did not meet those expectations in the seven weeks following that letter. On 29 April, Captain James once more wrote to Lord Randolph that, while he had no definite complaints to make, “I do not think his work is going on very satisfactorily.” James told Lord Randolph that he had spoken to Winston about this and suggested that he give his son “a little paternal advice and point out, what I have done, the absolute necessity of single-minded devotion to the immediate object before him.”

We do not know what if anything Lord Randolph said to his son, but the inference can be drawn that he must have said something, for in the next six weeks Winston’s efforts began to please Captain James. “He is working well and I think doing his best to get on,” James reported to Lord Randolph on 19 June, “and I have lately had no cause to complain of him.” While James added that Winston “ought to pass this time,” he concluded the letter by saying that “It would not do to let him know what I think of his chance of success as with his peculiar disposition, this might lead him to slacken off again.”

100 Years ago

Spring 1918 • Age 43

“Throwing a Bucket of Water over the Floor”

Peace with Russia at the start of the year allowed Germany to move millions of troops from the eastern front to the western front and come close to winning the war with a massive offensive in the spring of 1918. A good case can be made that without Churchill as Minister of Munitions since July 1917, Germany might well have succeeded.

2025 International Churchill Conference

On 19 January Churchill had written a letter to Prime Minister Lloyd George expressing his concern that the Government was not adequately preparing for the German offensive and warning that “The imminent danger is on the western front & the crisis will come before June.” In the event, the crisis came in March.

On 21 March, during Churchill’s fifth visit to France since becoming Minister of Munitions, the German offensive began. Churchill wrote in The World Crisis that the German offensive, “taking its scale and intensity, quantity and quality combined… must be regarded without exception as the greatest onslaught in the history of the world.” For half of the forty-mile front, Churchill wrote that “the density of the enemy’s formation provided an assaulting division for every thousand yards of ground, and attained the superiority of four to one….”

Churchill was right in the middle of the attack and experienced it first hand. He awoke in the early morning of 21 March to the sound of explosions of German mines under the British trenches, followed by “in less than one minute the most tremendous cannonade I shall ever hear…. The crash of the German shells bursting on our trench lines eight thousand yards away was so overpowering that the accession to the tumult of nearly two hundred [British] guns firing from much nearer could not even be distinguished.”

Within a week, the Germans had overrun Allied positions on the whole battlefield of the Somme, which the Germans had lost in 1916 with a staggering loss of life. Churchill returned to London on 23 March, and Lloyd George asked him how it would be possible to hold any positions on the battlefield now that their front lines had been breached. Churchill replied with a metaphor: “I answered that every offensive lost its force as it proceeded. It was like throwing a bucket of water over the floor. It first rushed forward, then soaked forward, and finally stopped altogether until another bucket could be brought.” The Germans might advance thirty or forty miles, Churchill explained, but eventually the front could be reconstituted.

Reassured, Lloyd George sent Churchill back to France to secure evidence that the British and French armies had the strength to withstand the German advance. While there, Churchill met with the French President Georges Clemenceau, and the two men toured the battlefields together at some considerable risk to their safety. They met Marshall Foch on 30 March, and Foch proceeded to give evidence of the accuracy of Churchill’s water bucket metaphor by marking on a map the huge gains made by Germany on the first day of the attack and then showed how each succeeding day, the German advance grew progressively smaller until they reached, in Churchill’s words, “this poor, weak, miserable little zone of invasion which was all that had been achieved on the last day. One felt what a wretched, petty compass it was compared to the mighty strides of the opening days. The hostile effort was exhausted.”

Churchill’s contribution to slowing the offensive began the year before when he first became Minister of Munitions in July 1917. He quickly reorganized the ministry by reducing fifty semi-independent, overlapping divisions into ten, whose leaders met with him daily as a Munitions Council. Sir Martin Gilbert notes that the result was that by 21 April 1918, less than a year later, Churchill’s ministry “had been able to send [British commander General] Haig twice as many guns as had been lost or destroyed since the start of the German offensive…the same was true of aircraft. He also had been able to replace every tank lost by one of a newer and better pattern.”

75 Years ago

Spring 1943 • Age 68

“What Stalin Would Think… I Cannot Imagine”

The spring of 1943 was kind to Churchill, with no major setbacks and only a few bumps in the road. On 7 April, American troops in western Tunisia linked up with the British Eighth Army. By 11 April, Montgomery had the remnants of the Afrika Corps in Tunisia on the run and had taken 25,000 prisoners. On 7 May, the British Army captured Tunis and the Americans seized Bizerta. By 9 May, 50,000 prisoners had been captured, including nine German Generals. By the end of May, the total had risen to more than 240,000 German and Italian prisoners. North Africa was at last free of the Axis occupation. The way was clear for the invasion of Sicily.

Sicily, however, was one of the bumps in the road. Churchill learned on 8 April that Eisenhower now opposed an invasion of Sicily, because there were two German divisions on the island as well as the expected six Italian divisions. Churchill responded in a memorandum that Ike’s view was “pusillanimous and defeatist doctrine” that would make the Allied governments “the laughing stock of the world.” Inasmuch as an Arctic convoy to the Russians had been cancelled because the escort ships were needed for the invasion of Sicily, he observed: “What Stalin would think when he has 185 German divisions on his front, I cannot imagine.”

Doubtless, Eisenhower was recalling the first contact between American and German forces when his soldiers were mauled at Kasserine Pass and lost 170 tanks. As a consequence of Eisenhower’s reluctance, Churchill resumed the heavy travel schedule he had endured during the first two months of the year, a schedule that had resulted in him being diagnosed with pneumonia that gave him a fever and a temperature of 102.

On 4 May, Churchill left England on the Queen Mary for his third trip to the United States during the war. Once in Washington, he was again invited by FDR to stay at the White House. While there, he and the President quickly reached an agreement giving the Sicily invasion the highest priority, Eisenhower’s reservations notwithstanding. The invasion of Italy would follow, with the focus shifting by November to preparations for a large-scale cross-Channel landing in May 1944.

Churchill also cleared up another bump in the road with FDR after having learned that the Americans had stopped exchanging information on the development of the atomic bomb. FDR ordered the resumption of this exchange.

Churchill did not return to England when the Washington conference ended. On 27 May, he took a flying boat to Gibraltar by way of Newfoundland, a seventeenhour flight. On 28 May, he flew for three hours in a converted Lancaster bomber to Algiers. On 1 June, after stopping at an American air base in the desert, he flew to Tunis, where he addressed a large number of the First Army troops who helped to drive the Axis forces from North Africa. On returning to Gibraltar in the Lancaster on 4 June, bad weather caused him to change his original plans to switch to a more comfortable flying boat and to stick with the Lancaster. That same day, a Pan American flying boat from Lisbon to England on a similar flight path was shot down by German fighter planes with all passengers killed, including the British actor Leslie Howard.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.