Finest Hour 180

Books, Arts, & Curiosities – A Gentlemanly Love of Liberty

August 3, 2018

Finest Hour 180, Spring 2018

Page 46

Review by James W. Muller

João Carlos Espada, The Anglo-American Tradition of Liberty: A View from Europe, Routledge, 2016, 212 pages, £115.00/$125.97, hardcover, ISBN 978–1472455727; £29.99/$49.95 paperback, 2018, ISBN 978–1138591592; $43.41 Kindle, ASIN B01GJZKJIC.

We learn on its first page that this book had its origin in a conversation in England between its Portuguese author as a young man and the Austrian-born British subject Karl Popper, a professor of political philosophy at the London School of Economics, then in his old age. The author, João Carlos Espada, with the woman who became his wife, had earlier taken part in the revolution that ended the long dictatorship in his country and was working as political adviser to Portugal’s democratically elected president Mario Soares. The president had arranged for Popper to deliver a lecture in Lisbon, where Espada had discussed with him his research on Popper’s critique of Marxism and his theory of democracy. Popper invited Espada to come to Britain to continue the discussion. Hence their conversation in 1988 at Popper’s house, which Espada tells us remained in his recollection after more than a quarter-century “as vivid as I recalled it when I left his home in the evening of that unforgettable first visit” (2).

The conversation took a particular turn by accident, when Espada espied, among the “highly selective collection” of books in Popper’s living room, not only works by Plato, Aristotle, Smith, Burke, Kant, and more recently Keynes and Hayek (1), but also

a huge shelf full of books by and on Winston Churchill. In my youthful openness, and my scholarly arrogance, I could not help putting the question: “why do you have so many books on Churchill? I thought he was mainly a politician.”

2024 International Churchill Conference

Thereupon Popper turned to Espada “and, with great intensity, said something like this: ‘sit down, my boy, I am afraid I have to teach you something very seriously.’” Then the old professor gave the young scholar “a full lecture” lasting “much more than an hour” about “Winston Churchill and the tradition of liberty among the English-speaking peoples” (2).

What Popper told Espada is that Churchill, as “the only leading politician, not only in Britain but in the whole of Europe, to have perceived the threat of Hitler almost a decade before he invaded Poland and started the Second World War,” had “saved western civilisation.” Knowing that that civilization could not survive without liberty, he had refused to compromise by making “a separate peace with Hitler,” although Britain was at a disadvantage against the Nazis’ military might. Had Hitler prevailed, western civilization would have been destroyed. Popper had so many books on Churchill “because he saved us.” He explained to Espada that the political culture of the English-speaking peoples combined “a deep love of liberty” and “a sense of duty,” which Popper called “the British mystery.” This culture was exemplified in the British gentleman, “who does not take himself too seriously,” but takes “his duties very seriously,” amid many who “speak only about their rights” (2). Popper rejected “the mistaken view” that the gentleman was a snob, pointing out that gentlemen sympathized with eccentrics and underdogs, and he took care to explain to his puzzled interlocutor what an underdog was. Then he told Espada that to “grasp the specificity of the Anglo-American tradition of liberty,” he would have to study and live in Britain or America (3).

What Popper told Espada is that Churchill, as “the only leading politician, not only in Britain but in the whole of Europe, to have perceived the threat of Hitler almost a decade before he invaded Poland and started the Second World War,” had “saved western civilisation.” Knowing that that civilization could not survive without liberty, he had refused to compromise by making “a separate peace with Hitler,” although Britain was at a disadvantage against the Nazis’ military might. Had Hitler prevailed, western civilization would have been destroyed. Popper had so many books on Churchill “because he saved us.” He explained to Espada that the political culture of the English-speaking peoples combined “a deep love of liberty” and “a sense of duty,” which Popper called “the British mystery.” This culture was exemplified in the British gentleman, “who does not take himself too seriously,” but takes “his duties very seriously,” amid many who “speak only about their rights” (2). Popper rejected “the mistaken view” that the gentleman was a snob, pointing out that gentlemen sympathized with eccentrics and underdogs, and he took care to explain to his puzzled interlocutor what an underdog was. Then he told Espada that to “grasp the specificity of the Anglo-American tradition of liberty,” he would have to study and live in Britain or America (3).

It was Allen Packwood, director of the Churchill Archives Centre at Churchill College, Cambridge, who later urged Espada to begin his book on Anglo-American liberty by recounting the conversation that had changed his life. Espada and his wife gave up comfortable positions in Lisbon so he could earn a doctoral degree at Oxford under the supervision of another naturalized Briton, Ralf Dahrendorf, who had been Popper’s student. Afterwards Espada taught in the United States at Brown, Stanford, and Georgetown. When he returned to Portugal, he founded the Institute for Political Studies at the Catholic University of Portugal in Lisbon. There the man who sought liberty through revolution in his youth learned what it takes to sustain it. As a professor of political science, Espada has taught a generation of students, some of them now among his faculty colleagues, his appreciation for the distinctive advantages of Anglo-American liberty. Eventually, as the leading lusophone Anglophile, Espada became a prominent expositor and proponent of that tradition on the continent of Europe. He takes pride in the fact that Britain’s oldest alliance, dating back to the fourteenth century, is with Portugal.

The Anglo-American Tradition of Liberty, which is in part Espada’s intellectual autobiography, reflects his vocation as a teacher. Often he tells us how he introduces authors whose works contributed to his education to his students or what students think of them. Aristotle says that the characteristic activity of friends is conversation, and the book’s tone is friendly and conversational: often Espada repeats an important point for the benefit of the reader, as a teacher would in class. In his acknowledgments he explains that his book “was not made according to a previously established plan” but “has emerged gradually,” mostly “from teaching” (ix), following a distinction made by the Austrian-born economist Friedrich Hayek between “organisation or made order and spontaneous or grown order” (65–66).

In successive chapters of the book Espada explains what he learned from a succession of scholars, some of whom he knew in person: first “personal influences” from Popper, Dahrendorf, British Labour peer and political theorist Raymond Plant, and American political writer Irving Kristol and historian Gertrude Himmelfarb; next lessons from “cold warriors,” French political theorist Raymond Aron, Hayek, British diplomat and academic Isaiah Berlin, philosophy professor Michael Oakeshott, and naturalized American political philosopher Leo Strauss; then proponents of “orderly liberty,” British philosopher Edmund Burke, American founder James Madison (whom Espada contrasts with the revolutionary French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau), and French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville.

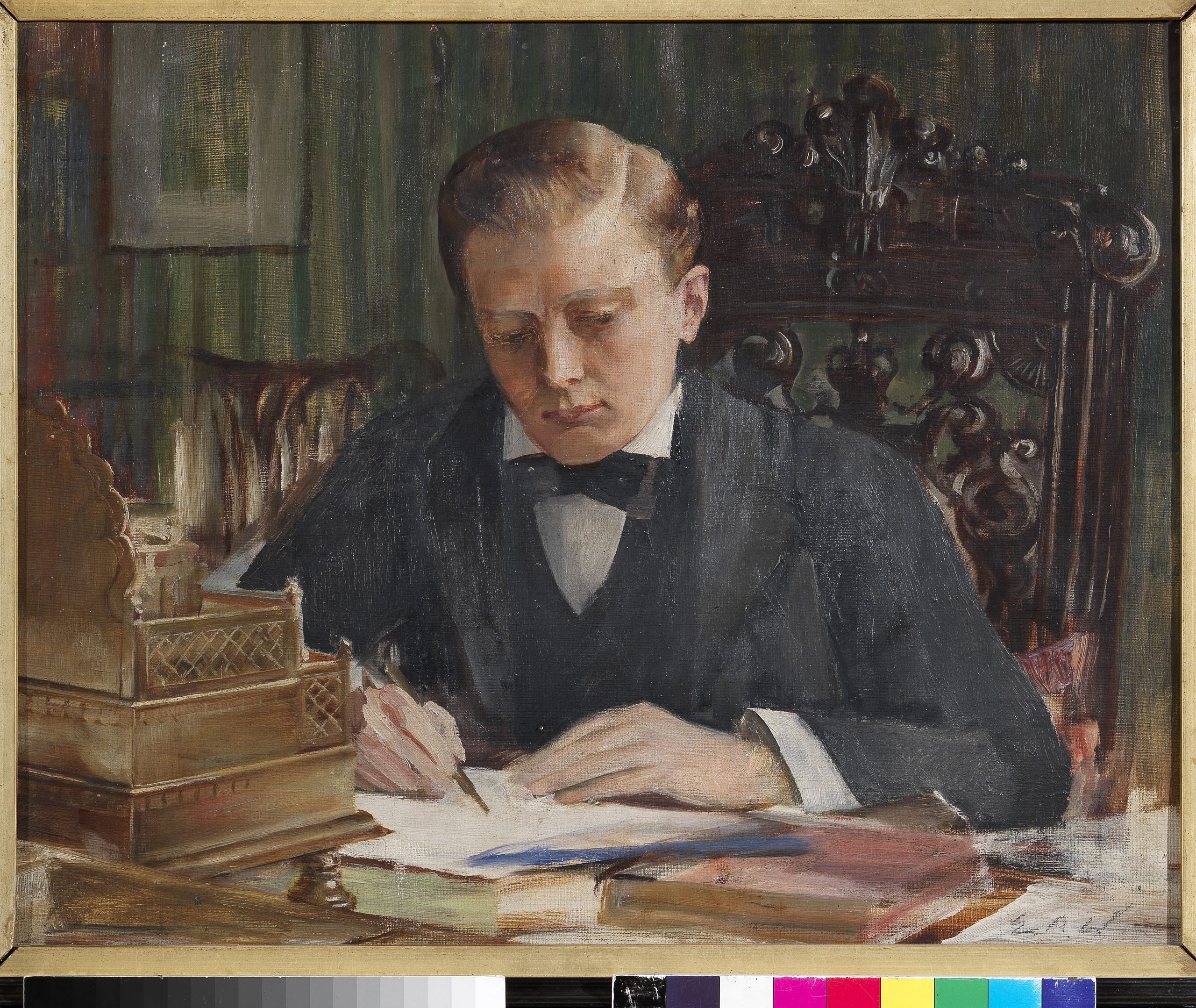

These essays lead up to his chapter on Winston S. Churchill, subtitled “The English-speaking peoples and the free world.” Espada quotes British historian Geoffrey Elton’s description of Churchill as, “quite simply, a great man” (188), and the cover of his book has a handsome photograph of Churchill’s statue in Parliament Square. Although the author admits that the statesman’s “works are not widely read and certainly not studied” among intellectuals, he claims that Churchill may have been the greatest twentieth-century “representative of the western tradition of liberty” (139). His lifelong opposition to communism and Nazism, to tyranny from the left or from the right, arose from his devotion to the British “tradition of limited government and of liberty under law” (151).

One of Espada’s favorite quotations is from the British political writer Anthony Quinton, who argues that “the effect of the importation of Locke’s doctrines into France was much like that of alcohol on an empty stomach” (6; cf. 7, 102, 106, 108, 159, 186), making revolution in France bolder, bloodier, and brighter than constitutional changes in Britain for want of a tradition of limited government to restrain excesses of popular rule. Espada emphasizes the importance of Churchill’s argument in A History of the English-Speaking Peoples that liberty, the rule of law, and agreement that a man’s home is his castle allow British subjects to achieve happiness. Thus Espada’s book offers a different view of Churchill, making him an intellectual defender of the liberty that even now allows Englishmen to live a contented life, rather than a backward-looking statesman longing for the Victorian era. In the last chapters of the book, written before Britain’s vote to leave the European Union, Espada, who is not anti-European, applies the spirit of Anglo-American liberty to Europe’s twenty-first century troubles by urging European statesmen to stop longing for continental uniformity and respect differences in the settled ways of life of their distinct European nations.

The first version of this book was published in Portuguese as A Tradição Anglo-Americana da Liberdade: Um Olhar Europeu (Lisboa: Principia, 2008). The revised and expanded English version has just been reissued in a paperback edition more affordable than the expensive hardcover edition published in 2016, making this fine book by an academic adviser of the International Churchill Society and the president of the International Churchill Society, Portugal, available to a wider circle of readers interested in gaining a deeper understanding of Churchill.

James W. Muller is Professor of Political Science at the University of Alaska, Anchorage, and chairman of the ICS Board of Academic Advisers.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.