Finest Hour 180

“School Display”: Churchill’s First Published Work

August 20, 2018

Finest Hour 180, Spring 2018

Page 34

By Fred Glueckstein

Fred Glueckstein wishes to thank Miss Tace Fox, Archivist and Record Manager at Harrow School, London for her invaluable assistance in researching the archives on his behalf.

Young Winston Churchill had just turned seventeen when his first published work was printed in December 1891 in the pages of the Harrow School’s weekly newspaper The Harrovian under the pseudonym Junius Junior.

Churchill’s first published work raises a number of curious questions. Why did he write the letter? What did the letter express? Was there a reason he used the pseudonym Junius Junior, and was there a response by schoolmates, or the school administration?

Letters to the Editor

Winston Churchill entered Harrow, an independent boarding school for boys in Middlesex, on 17 April 1888. While there, he took up fencing and spent a good deal of time in the gymnasium. Churchill eventually became fencing champion of the school in December 1892.

2024 International Churchill Conference

On 8 October 1891, Churchill had his first letter published in The Harrovian. It was a two-sentence appeal for more convenient opening hours for the school library. In writing the paper, Churchill would have been cognizant of The Harrovian’s policy, which appeared regularly in its pages, and read:

CORRESPONDENCE: The Editors will be glad to receive any correspondence from Harrovians, past and present; but in all cases the writer must send his name and address—not necessarily for publication, but as a guarantee of good faith. The editors do not always endorse the opinions of their correspondents. All communications should be legibly written on one side of the paper only, and addressed to the Editors of “THE HARROVIAN,” care of Mr. Overhead, Harrow.

Six weeks later, on 19 December 1891, Churchill wrote a much lengthier letter about the school’s lack of encouragement to boys to take a greater interest in the gymnasium’s activities. This letter, written under the pseudonym Junius Junior, was regarded by Churchill’s son Randolph as his father’s first true published work.1

First Letter from Junius

Dear Sirs, Great as the School undoubtedly is, it cannot afford to allow any of its mechanism to fall out of gear. When a public school possesses a Gymnasium, and especially such a fine one as ours, it becomes the duty of every one of us to see that it should not go to rack and ruin. I am far from asserting that the Gymnasium has gone completely down the hill, but it is no secret that it is going that way. This being so, it is for each and all to see that it goes no further in that direction.

We have lately been startled by an imposing announcement that the “School Display” would take place in the Gymnasium on Saturday, 12th December. Whether those who went to see this “Display” were satisfied is more than I can say, but everyone will assent when I state that the notice would have been much more correct, had it proclaimed that the Aldershot Staff would give a Display in the Gymnasium on Saturday, 12th December.

A School Assault-of-Arms is intended to bring out our own talent. The Aldershot Staff can be seen elsewhere, but untold gold could not purchase the services of the School. Among the performers, the School was conspicuous by its absence. The endeavour to prove that four equalled eight failed signally. Picture the “Display” without the assistance of the Aldershot Sergeants—it would indeed have been a “show.”

Now, what I ask, and what the School ought to ask, and will ask, is—Why did so few boys do anything? Why was the performance watched from the gallery by two members of the School Eight? Why is it that when, within a hundred yards of the Gymnasium, there is an athlete, whose sparring has ever been the guarantee of a full house, boxing was entirely omitted from the programme? It seems that to these questions certain answers might be made. “The School,” it might be said, “were asked and wouldn’t, the boxer has been approached and has refused, the members of the Eight have been exhorted, but they have declined with thanks.”

If that is so, there must surely be some reason for this spontaneous refusal, and to find this reason I turn to the Editors of The Harrovian.

There is another excuse that may be set forth. It may be urged that no one else was good enough to perform. In that case no further question is necessary. If, out of all who go to the Gymnasium, only five per annum are fit to perform before the School at the Assault, there is obviously a hitch somewhere.

All these things that I have enumerated serve to suggest that there is “something rotten in the State of Denmark.” I have merely stated facts—it is not for me to offer an explanation of them. To you, sirs, as directors of public opinion, it belongs to lay bare the weakness. Could I not propose that some of your unemployed special correspondents might be set to work to unravel the mystery, and to collect material wherewith these questions may be answered.

The School itself has an ancient history; even the Gymnasium dates back to a Tudor. In those days they were not wont to “Risk” [Tudor Risk was the first Superintendent of Gymnasium, 1874–87] the success of the School Assault-of-Arms in the manner in which it was done on Saturday last. For three years the Assaults have been getting worse and worse. First the Midgets, then the Board School, and, finally, the Aldershot Staff have been called in to supplement the scanty programme. It is time there should be a change, and I rely on your influential columns to work that change.

Who Is This Junius?

We can only speculate about Churchill’s use of the pseudonym Junius Junior. His interest in history, however, argues for the following explanation. Letters of Junius was a collection of private and open letters critical of the government of King George III from an anonymous polemicist (Junius), as well as other letters in-reply from people to whom Junius had written between 1769 and 1772. The collection was published in two volumes in 1772 by Henry Sampson Woodfall, the owner and editor of a London newspaper, the Public Advertiser.

It appears likely that Churchill’s chosen pseudonym was a reference to the the anonymous polemicist of the eighteenth century. Certainly, like the original, Churchill’s letter attracted replies also written under pen names such as that from “Octavus” published on 18 February 1892: “As to the letter which appeared in your last issue by ‘Junius Junior,’ there is no doubt that he is perfectly right in saying that the Gymnasium is going downhill. It is certainly not what it used to be. The competitions were more keenly competed for, the assaults were a greater success, and the standard of the Eight was much higher; and, I am sure, it is the unanimous desire of all well-wishers of the Gymnasium that this falling-off should not continue, but that every year should find Harrow better, keener, and more fitted for carrying off the Aldershot Shield than the preceding one.”

Another student styled himself “Aequitas Junior,” while acknowledging Junius Junior’s fervor for the welfare of the gymnasium but suggesting that his argument “seems to be just a trifle too severe on its present condition.” Aequitas Junior argued that during the last few years the proportion of the performances done at the school by outsiders had always been rather small and, in fact, the last time there were numerically far less outsiders than usual.

Aequitas Junior also wrote that a combination of accidents resulted in the members of the Eight having reasons for their absence, which included such unforeseen accidents as a fractured wrist; illness, and inability to practice because of an approaching scholarship. He ended: “It also strikes one as somewhat strange that your correspondent should say ‘the Eight have been exhorted, but they have declined with thanks.’ The absentees all had a very valid reason for their absence.”

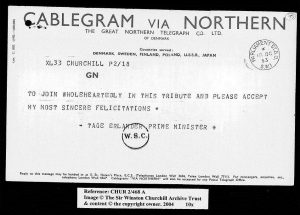

Exasperated with Aequitas Junior, Churchill wrote a second letter to The Harrovian dated 17 March 1892. In publishing Churchill’s letter, The Harrovian’s editor Leo Amery (who later served in Churchill’s Cabinet during the war) added a note: “We have omitted a portion of our correspondent’s letter, which seemed to us to exceed the limits of fair criticism.”2

Second Letter from Junius

Dear Sirs, When fired by the lamentable failure of the Assault-at-Arms I wrote my last letter to you, I expected an answer. I had hoped to see an emphatic denial of the charges which I made. I had looked for an explanation, offered not only to one, but to all of my questions.

It seems, however, that I was mistaken. Your correspondent, “Aequitas Junior,” does not answer my letter: he avoids my main statement and seeks to champion his cause from a side issue; in fact, sirs, I had to read his letter several times before I could determine whether it was intended for an answer or a confirmation of what I wrote. But since it explains the one sentence of my letter which he is good enough to quote, I have decided to consider it as an answer.

I will not pause to criticise his style nor comment on his probable motives, though I am inclined to think that both are equally poor. Beginning with his opening sentences we find that he thinks I have been “just a trifle too severe” on the conditions of the Gymnasium. I may have been. I will not dispute the point. But if the statements detailed at length in my last letter were only incorrect in one particular, and if the inferences I drew were only “just a trifle too severe,” the state of things must indeed be bad.

As to the rest of the letter, it does not answer or concern me. He seems, however, to be under the impression that I compared the School Eight with the Aldershot staff. I deny it. Such a comparison, if indeed possible, would have been too odious….

I assert, then, that my questions remain unanswered and my charges unrefuted. If what I stated were false, surely it were easy to prove it so, and if true, who should object? And in the presence of this half-hearted reply, which says, I allow, all there is to be said, and in the presence of the confirmation afforded to me by “Octavus,” I appeal to the readers of The Harrovian to decide whether in my last letter I stated fact or falsehood.

The Headmaster and Churchill

In 1941 Amery recalled: “As schoolboy editor of The Harrovian it fell to me to be the Prime Minister’s first editor and press censor. He submitted a trilogy of articles on Ducker [the school swimming pool], the gym, and the school workshop, breezy, entertaining and frankly critical of the existing administration of all these departments.”

“I can still see,” Amery mused, “the look of misery on his face as, in spite of his impassioned protests, I blue pencilled out some of his best jibes. However, even my pedantic zeal for the Victorian respectability of The Harrovian did not altogether save the expurgated text from criticism by the authorities concerned.”

Amery continued, “Mr. Welldon, the Headmaster, summoned the young author to his study and thus addressed him: ‘My boy, I have observed certain articles which have recently appeared in The Harrovian, of a character not calculated to increase the respect of the boys for the constituted authorities of the School. As The Harrovian is anonymous I shall not dream of inquiring who wrote those articles, but if any more of the same sort appear, it might become my painful duty to swish you!’ This, at least, is the story as Mr. Welldon more than once related it to me with great gusto.”3

Avery believed Churchill’s letters to The Harrovian reflected his schooling in the Fourth Form of Mr. R. Somervell, whose teachings provided him with a complete knowledge of the elements of the English language. Churchill’s writing under the pseudonym Junius Junior foretold his great gifts as a master of the spoken and written word, and it represented Churchill’s first authenticated published work.

Endnotes

1. Randolph S. Churchill, Winston S. Churchill, Volume I, Youth 1874–1900 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2005), p. 177.

2. William Manchester, The Last Lion: Visions of Glory 1874– 1932 (New York: Little Brown and Company, 1983), p. 156.

3. E. D. W. Chaplin, ed., Winston Churchill and Harrow: Memories of the Prime Minister’s Schooldays 1888–1892 (London: Harrow School Book Shop, 1941), pp. 22–23.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.