Finest Hour 175

Sarah Churchill: More Than a Thread

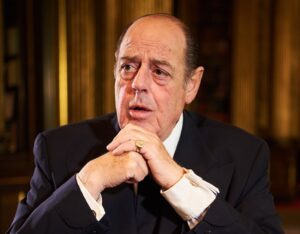

Winston and Sarah in Africa during the Second World War (photo: Imperial War Museum)

April 17, 2017

Finest Hour 175, Winter 2017

Page 22

By Catherine Katz

Catherine Katz earned degrees in history at Harvard and Cambridge. She is working on a biography of Sarah Churchill.

Sarah Churchill was the essence of the modern woman living in an era that was not yet ready for her.

Judged in her day as a “Bolshie Deb,” a runaway bride, a rising star of London’s West End, and “the one that’s always in trouble,” she was in her own words endlessly “written up, written down and always written about” as “a woman who happened to be a daughter of one of the ‘greats’ of history.”1

To describe Sarah merely as Winston Churchill’s daughter would be to tell only half her story. While Sarah was certainly her father’s daughter in both fact and temperament, restricting our understanding of her to this narrow lens belies her fierce independence, depth, intelligence, professional success, and personal impact on the lives of some of the most extraordinary figures of her era.

Though a tabloid fixture in her own times, Sarah Churchill is little known today. Amongst modern audiences who are familiar with her story, her life is often condensed into a few short and unjustly unforgiving biographical lines: Sarah Millicent Hermione, the third child of Winston and Clementine Churchill, was born in October 1914, two months after the First World War commenced. She became a moderately successful actress on the stage and screen, was thrice married (with two of her husbands being entirely unsuitable), and at times grappled tragically with alcoholism and financial difficulties, particularly towards the end of her life.

In spite of this limited understanding of Sarah Churchill today, contemporaries describe this complex woman differently. A journalist who knew her recalled: “More than anybody I have ever interviewed, she was a life enhancer, who made everything seem rosier, more entertaining, more glamorous. At the same time she was vulnerable. She wanted you to like her and was touched if you did.”2

Reading Sarah’s own words brings the color and vitality of her life into focus. From adolescence, Sarah struggled between upholding the expectations that her position as a Churchill wrought and establishing her name and her career beyond the scope of her family. Though she could easily have lived in comfort in her father’s aura until the end of her days, Sarah sought to be the sovereign of her own life, and in doing so became the most independently successful member of her family after Winston himself.

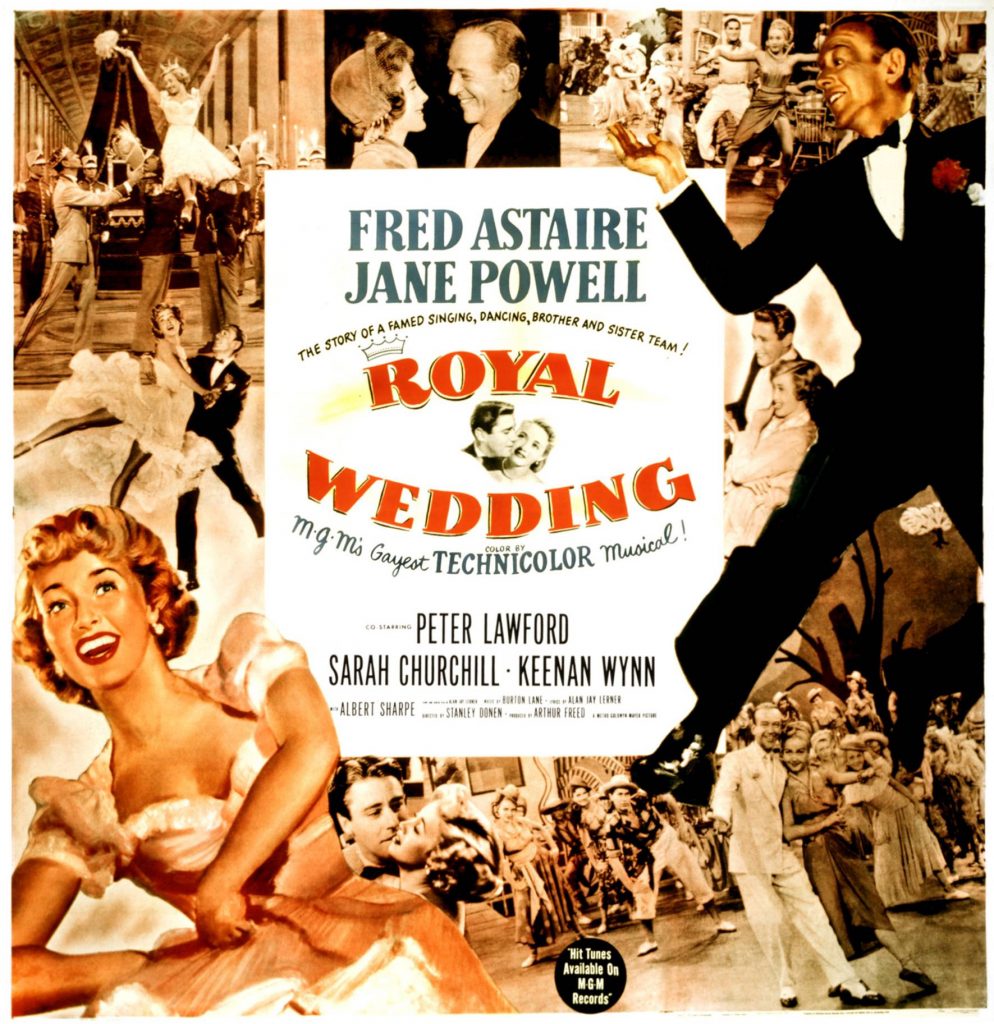

As a young woman, Sarah rejected the life expected of an aristocratic debutante. Lovingly nicknamed the “Mule” by her family because of her stubborn nature, she fought for a career of her own on the stage and marriage in 1936 to Austrian-born Jewish comedian and actor Vic Oliver. Though this marriage was not to last, her stage career blossomed. She starred in several popular productions prior to the outbreak of war but interrupted her career to join the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force and serve her country as a WAAF. Returning to the dramatic arts after the war, Sarah made the leap from stage to screen, from London’s West End to Hollywood. After eloping with society photographer Anthony Beauchamp in 1949, the pinnacle of her film career came in 1951 when she acted and danced opposite Fred Astaire in the film Royal Wedding. The pinnacle of personal happiness arrived in 1962 with her third marriage, this time to Lord Audley, the love of her life. His death, just fifteen months after their wedding, left Sarah devastated. And though her later years bore significant challenges, she authored six books, including poetry collections, a loving tribute to her father in A Thread in the Tapestry (1966), and her own memoir Keep on Dancing (1981).

While dancing with Fred Astaire is enough to make for a memorable life, it was the war that gave Sarah— much like her father—the opportunity to be her best. The necessities imposed by war broke down some of the barriers that had constrained her personally and professionally, giving this modern woman the chance to contribute and flourish. In doing so, she proved her true Churchillian character, succeeding as a natural-born ambassador for her country.

In a sense, life began anew for Sarah in 1940. After four years of marriage to Vic Oliver, She had grown and matured into a determined woman. While their respective careers and his philandering had stressed their relationship, the war brought on their inevitable separation. Oliver had become an American citizen in 1936—in part to marry Sarah—and when war erupted between Britain and Germany, the US government required all American citizens in England to return home or else lose their citizenship.

Sarah faced a crucial choice. She could return to America with her husband, or she could say goodbye. In a June 1940 letter to her mother, she explained her weighty predicament, concluding, “When I think of leaving England now—of going away from you all—at this critical hour—I can’t tell you what it does to me.”3 Sarah chose to stay, both to do her bit for her country and to discover what life held in store as her own master.

Though determinedly independent in her career, Sarah wrote in her memoir, “I think the only time I asked my father to exert his influence on my behalf was, ironically, to get me out of the theater.” She spoke to her father and—less than forty-eight hours later—became a WAAF.4

Initially, her WAAF commanding officers offered her an administrative position, assuming easy office work and quick promotion would be most appropriate for the Prime Minister’s daughter. Sarah was intent, however, on filling an intellectually challenging position, where she could make a meaningful contribution towards material results. She told her mother: “I do not mind the discomforts; I only want to find something I can do well.” Resolved, she interviewed for and was accepted into the Photographic Interpretation Unit of the RAF Intelligence Branch at Medmenham. In another letter to Clementine (in which she added two exclamation points beside her name, rank and serial number), Sarah elatedly wrote, “I must say one feels ridiculously proud of one’s uniform and all it stands for.”5

As a Section Officer in the Photographic Interpretation Unit, which analyzed aerial reconnaissance photos for European and North African operations, Sarah scrutinized images to identify critical targets for Allied bombers. The work was demanding, with twelve-hour overnight shifts and eye exams every eight weeks. Perhaps the most challenging, yet gratifying phase of her work came in advance of Operation Torch, during which Sarah’s unit worked in conjunction with ground intelligence to prepare for the Allied invasion of North Africa in 1942.

While Sarah found the independence and sense of purpose she craved at RAF Medmenham, the fact that she was the Prime Minister’s daughter required her to play a role unlike that of any of her fellow WAAFs. As a result of her unique position, she became a participant in several of the most politically charged moments in twentieth-century history. Winston and Clementine had decided that a member of the family should accompany the Prime Minster on his international travels as a trusted supporter and protector. Mary Churchill attended the Quebec and Potsdam Conferences, while Sarah joined her father as his aide-de-camp at the meetings between the “Big Three” at Cairo, Tehran, and Yalta. Sarah’s letters to her mother provide some of the most intimate commentary on these events that shaped the decades that followed.

In November 1943, Sarah travelled with her father to Cairo in HMS Renown to discuss Pacific theatre strategy with Franklin Roosevelt and Chinese President Chiang Kai-Shek. From there, they continued on to Tehran to meet Joseph Stalin and outline the strategy for a second front against Germany. Sarah— dressed proudly in her WAAF uniform—was the only female member of the delegation.

Stopping in Malta en route to Cairo, the RAF flew several members of the group in Mosquito bombers over Sicily. Looking at the ground beneath her, Sarah felt as if she had been there before: having analyzed photos of the Italian peninsula for months on end, she did not need a map to know exactly where she was. She wrote to her mother, “The only unfamiliar thing of course was the color. I knew it all in black and white—and it was pink.”6

The group arrived in Cairo on 22 November. While meetings between the heads of government transpired, Sarah waited in an antechamber with the Chinese aides. Suddenly, she was summoned to join the discussion inside. “We sat in a circle with two interpreters and had about 15 minutes conversation,” she told her mother, “Papa with Chiang and me with Madame Chiang,” who, Sarah noted, was suffering from “pink eye!” Despite her ailment, the Chinese First Lady was a striking and intelligent individual: “Papa was impressed by her—and there is no doubt that she is far and away the best interpreter.”7

With the imposing figure of Madame Chiang fresh in Sarah’s mind, the delegation moved on to Tehran on 28 November. After long days in Cairo and a grueling flight, Winston Churchill was exhausted and suffered from laryngitis. Sarah wrote, “Uncle Joe was already there and Papa wanted to start right there and then.” As her father’s guardian, she knew that meeting with Stalin in such a reduced state would not put her father in a strong position to negotiate. Sarah and Lord Moran, Churchill’s doctor, tried to persuade him to delay “and got [their] heads bitten off.” Ultimately he agreed to wait until he had rested, a decision that proved advantageous.8

The Prime Minster’s sixty-ninth birthday fell on the third day of the conference, which Sarah reported was the highlight of the trip, “not only because of all the ‘great’ that were gathered, but because of why they were gathered, and most of all—because of how they really get along….There was a great roar of laughter, the kind of laughter that is only heard among friends.” “Whatever follows,” she continued, “one couldn’t help but feel that a genuine desire for friendship was sown that night.”9

The Big Three gathered next in February 1945 to discuss European postwar organization at Yalta. After landing in Saki on the Crimean Peninsula, the delegations endured a harrowing six-hour drive over rough, ransacked Russian terrain, finally arriving at Vorontsov Palace— the only accommodation left standing. Tension and suspicion replaced the ebullient atmosphere at Tehran, with each of the leaders advocating a different vision for Europe’s future. After long sessions throughout the afternoon and evening, Sarah stayed up half the night discussing strategy and the fate of Poland with her father and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden.

Sarah had impressed Roosevelt at Tehran, prompting him to bring his own daughter Anna to Yalta as his aide-de-camp. Averell Harriman, the American Ambassador to the USSR, similarly brought his daughter Kathleen. Between conference sessions, the three women ventured out to Sevastopol, where they beheld the scars of war. Every house was “shattered,” and Romanian prisoners queued for their meager rations. Sarah told Clementine, “One has seen similar queues of hopeless stunned humans on the films—but in reality it is too terrible.” That night, when she reported what she had seen, her father solemnly told her, “Tonight the sun goes down on more suffering than ever before in the world.”10

While the Yalta Conference made Sarah a witness to war’s utter devastation, it also made her party to the harbingers of geopolitical change for Britain in the postwar world. At Tehran, Sarah had written to her mother of the admiration she felt for President Roosevelt and the genuine compassion and understanding she felt existed between the American leader and his British counterparts; at Yalta, however, FDR’s obvious effort to placate the Soviet Union ahead of Britain smacked of betrayal. During a conversation with Anna Roosevelt, Sarah learned that the President intended to leave Yalta to meet with Saudi Arabian leader Ibn Saud before all parties were satisfied with the plans for peace in postwar Europe. Disgusted, Sarah told Lord Moran, “As if…the conference isn’t so much more important than anything else.”11 The next day, Roosevelt departed promptly, and Stalin, “like some genie, just disappeared.”12

The Second World War gave Sarah Churchill an independent life befitting her talents and ambitions, while simultaneously reinforcing her identity as Winston Churchill’s daughter. It allowed this modern woman to surpass the expectations she held for herself, and those that others held for her. As her father’s aide-decamp, Sarah became an intimate witness to and actor in the crucial events that shaped history in a way that few women did during the Second World War. Her abilities and composure earned her the respect of the leaders of her time, prompting them to open doors for the women in their own lives to follow Sarah’s example.

The independence and confidence Sarah gained during the war fuelled her career in its aftermath. Though she never sought fame on the screen, preferring to act in live performances on stage, she boldly appeared in one of the first Italian films made in the war’s aftermath and moved to America as a single woman to pursue intriguing career opportunities that Hollywood provided.

But perhaps what brought her the most personal happiness was that her wartime role created a new closeness between Sarah and her parents—her father in particular. After all they had witnessed together at Tehran and Yalta, Winston turned to Sarah in times of difficulty throughout the rest of his life. With the end of war in sight, Sarah wrote to her mother on 7 April 1945, reflecting on all that had transpired: “The real happiness of these last years has been getting to know both you and Papa—I have always loved you, but not always known you, and this sudden discovery of you both is like stumbling on a goldmine!”13 And when it was all over, she wrote to her father, “All my love to you and Mummie—you’re terrific—both of you—wow, wow, and re-wow forever.”14

Endnotes

1. Sarah Churchill, Keep on Dancing (New York: Coward McCann & Geoghegan, 1981), pp. 9–10 and 321.

2. Lynne Olson, Citizens of London: The Americans Who Stood with Britain in Its Darkest, Finest Hour (New York: Random House, 2010), p. 113.

3. Letter to Clementine Churchill, 30 June 1940, SCHL 1/1/6, Sarah Churchill Papers, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge.

4. Churchill, Keep on Dancing, pp. 98–99.

5. Letter #1 to Clementine Churchill, 28 October 1941, SCHL 1/1/6; Letter #2 to Clementine Churchill, 28 October 1941, SCHL 1/1/6.

6. Letter to Clementine Churchill, 19 November 1943, SCHL 1/1/7.

7. Letter to Clementine Churchill, 23 November 1943, SCHL 1/1/7.

8. Letter to Clementine Churchill, 4 December 1943, SCHL 1/1/7.

9. Ibid.

10. Letter to Clementine Churchill, 6 February 1945, SCHL 1/1/8.

11. S. M. Plokhy, Yalta: The Price of Peace (London: Viking, 2010), p. 310.

12. Letter to Clementine Churchill, 12 February 1945, SCHL 1/1/8.

13. Letter to Clementine Churchill, 7 April 1945, SCHL 1/1/8.

14. Letter to Winston Churchill, 27 July 1945, SCHL 1/1/8.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.