Finest Hour 175

Jennie Churchill and Her Attempts to Be an Independent Woman

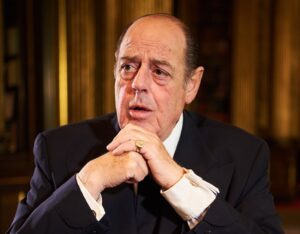

Lady Randolph (Jennie) Churchill

April 3, 2017

Finest Hour 175, Winter 2017

Page 06

By Anne Sebba

Anne Sebba is the author of Les Parisiennes: How the Women of Paris Lived, Loved and Died under Nazi Occupation (St Martin’s Press, 2016). Quotations in this article are from her biography American Jennie: The Remarkable Life of Lady Randolph Churchill (2007).

A few years after she was married, Jennie Jerome wrote to her mother Clara trying to close off a conversation: “Money is such a hateful subject to me just now…don’t let us talk about it.” She was explaining why she could not attend as many balls as she wished and why her expenses were so great. From the day she married Lord Randolph Churchill on 15 April 1874 in Paris, money (or the lack of it) dogged her life. The wedding could only take place the day after the money forming her marriage settlement had arrived. Leonard Jerome was finally prevailed upon to agree to a capital sum of £50,000, yielding approximately £2,000, a year of which Jennie was allowed to keep half as “pin money” and Randolph the other half. Without it, there would have been no wedding.

Born in 1854, Jennie’s upbringing and education had all been geared towards fulfilling her destiny, which, for a young girl of social standing, meant making a good marriage, preferably to a British aristocrat. Jennie was a highly talented pianist and extremely well read, as well as strikingly beautiful. Yet these attributes were merely accomplishments, not a means of earning a living. Nonetheless, Lord Randolph’s career as a Member of Parliament (and a second son) earned him nothing, and although he was briefly appointed to the Cabinet in 1886—a paid appointment—he resigned after six months on a matter of principle, believing he would be called back. But he never was and died in 1895.

Married at twenty, widowed by forty, Jennie now had to think to the future. And so, five years after Randolph’s death, she remarried. Although her marriage to the young and handsome George Cornwallis-West was a partnership which only increased her worries about money, arguably her precarious financial situation also fired a deep creative spark as she refused to give up on style, moved to an exquisitely romantic sixteenth century house less than an hour north of London, and set about trying to establish a reputation as a writer.

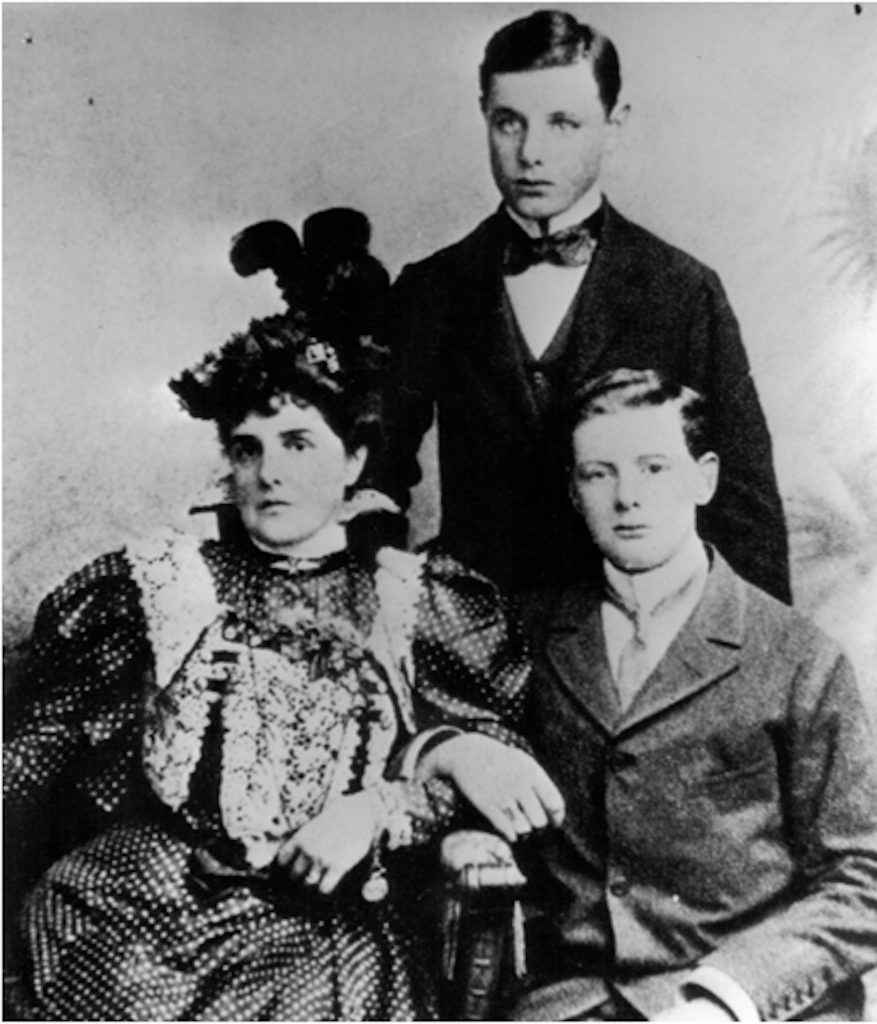

Entirely self-taught, Jennie worked first with Winston on a luxury magazine they called the Anglo-Saxon Review [see FH 174]. But this proved a drain on income so, once publication ceased, Jennie’s main attempt at generating money focused on her own ability to write. Curbing expenditure was always a nettle too sharp to grasp. Winston proffered stylistic advice when she sent him work in progress and was good at chivvying her on because he, too, was self-taught. He told her how to group her ideas, to make up her mind as to exactly what was her intention in each paragraph before she started, and to be prepared for constant rewriting.

At the same time, both her sons, Winston and Jack, constantly warned of the dangers of her extravagance, to which she responded not by cutting back but by trying to find ways to fund the spendthrift ways which their income did not begin to match. George, not without his own profligacies, wrote later that in money matters Jennie was without any sense of proportion. “The value of money meant nothing to her: what counted with her were the things she got for money, not the amount she had to pay for them.” Four years into this new marriage, Winston told his mother that he looked with very grave anxiety into the future. Heeding these warnings, Jennie made new efforts to fund her life. She was a natural communicator and by 1907 was writing in earnest, being pressed by her publishers to deliver a memoir, a book if gossipy enough, that Edwardian society was drooling to read.

The Reminiscences of Lady Randolph Churchill, published in 1908 by Edward Arnold in England and Century in the US, was politely reviewed, considered a pleasant if somewhat superficial insight into society, and went through several editions. It was dedicated to Winston and Jack, but, as she made clear in the preface, “there may be some to whom these Reminiscences will be interesting chiefly in virtue of what is left unsaid.” It failed to relieve her financial worries.

The Theatre

As she took stock of her life, Jennie’s natural love of drama—she had grown up with a theatre in her childhood home—spurred her on to try her hand at playwriting. This activity would bring her close to the theatrical world she adored as well as, she hoped, make money. Jennie may not have had a deep intellect but she had a genuine interest in literary matters, politics, music, and letters and was constantly reading. George believed she was a brilliant conversationalist because she remembered so much of what she had read. Writing a play would, if she could pull it off, take her into a new league; having her work staged was a challenge she had been ruminating on for some time. But she never found writing easy and, as soon as she had completed a draft, sent it to Winston for his comments. He was far from encouraging: “I do not think that the work is sufficiently strong in originality of plot, in situation, in dialogue, or in characterisation to justify its public production.”

Nonetheless Jennie ploughed on and, according to George, it was her idea to have Mrs Patrick Campbell, the most celebrated actress of her day, not only produce it but take the leading role. She was eleven or so years younger than Jennie, beautiful and witty with a talent for playing complex and fascinating women. Mrs. Pat (as she was known) may have been attracted to the idea of producing it herself partly because she knew that high society and royalty would take a close interest. But, long before opening day, in spite of the professional cast, multiple weaknesses were all too apparent.

His Borrowed Plumes,—or as some of the cast had taken to calling it “His Sorrowful Blooms”—was a highly autobiographical play within a play. Fabia Sumner, the heroine, was an authoress who led a busy social life and needed to write to make money. Her husband, Major Percival Sumner, was jealous of her success and began an affair. In the play everything ends happily with Fabia and her husband declaring undying love. In life, however, George was “seriously attracted” to Mrs. Pat and everything did not end happily.

The play opened at the Hicks Theatre (later The Globe, now The Gielgud) in Shaftesbury Avenue to a full house packed with a glittering mixture of celebrities and aristocrats. Winston sat in a box with his mother and stepfather looking, apparently, profoundly nervous. Despite the excitement surrounding the gala opening, it survived two weeks. It was not a bad play, in fact it was quite amusing, as the critics concurred. Max Beerbohm even described it as “very good entertainment….” Plays challenging traditional views of marriage and divorce and even female sexuality, however, had been around for a decade or so, and, compared with the scandalous reactions to Henrik Ibsen dramas, His Borrowed Plumes seemed rather tame.

George later remarked, “had the original intention been adhered to and only four matinees given these would have paid for the whole cost of production as people flocked to see a play written by one brilliant woman and produced by another. But it was kept on and, alas, being an indifferent play, it was another instance of an unsuccessful enterprise” (author’s italics).

Brush up Your Shakespeare

Slowly, as it dawned on Jennie that writing plays, however much fun, caused yet another drain on her resources, she conceived her most grandiose scheme, the project that best defined her identity as a lover of English culture and history yet perhaps could only have been driven by an American. That she rose above the drama in her private life to create a magnificent public pageant drawing on English history and literature is a tribute to her enormous personal courage as well as her love for her adopted land. Financially, it was a spectacular failure.

In May 1910, Edward VII died, and, in the weeks before the Coronation of George V, Jennie was working frantically to organise a Shakespearean Ball. This was part of an appeal she was helping to launch to raise at least £10,000 to go towards buying a site opposite the Victoria and Albert Museum in Kensington, South London to build a National Theatre where high-quality productions, not necessarily dependent on box office popularity, could be mounted. Several noted hostesses were giving balls to welcome the new era, but none was so original or magnificent as Jennie’s, nor with such a purpose. Jennie had persuaded Edwin Lutyens to transform the Albert Hall into a beguiling Elizabethan-Italianate garden, where six hundred or so guests—dressed in Shakespearean costumes—could dance until dawn. Jennie went as Olivia and George as Sebastian from Twelfth Night. She understood how crucial it was to have the Royal Family on her side and succeeded in persuading King George V and Queen Mary to grace the occasion, forty-eight hours before their Coronation.

Like everything Jennie did, no expense was spared to make the event compellingly authentic. The Albert Hall, under a fake blue sky replacing the dark red brick Victorian roof, became a faithful reincarnation of Tudor England. There was clipped yew in the shape of topiary birds, twirling grapevine on the marble terrace and a balcony where supper was served. The night was a dramatic success. But it was only one night. Soon Jennie was dreaming up something on a far greater scale with much wider appeal but with the same goal of promoting a Shakespeare Memorial and a National Theatre. She had in mind an ambitious scheme to stage an enormous exhibition at Earl’s Court, a generally derelict area of West London, which boasted a large stadium but little else, to be called “Shakespeare’s England.” Again she engaged Edwin Lutyens, this time to rebuild Earl’s Court “into a wonderful OLD London of the Elizabethan period with the picturesque wooden houses of the time, the same quaint old streets— some of them only a few feet wide—and the same curious old world atmosphere of that epoch of chivalry and romance.” Once again, she hoped it might be financially profitable for her personally as well as an important gift to posterity.

Jennie set about arranging for an Organising Committee as well as an Executive Committee, but all she wanted of the two Committees was their cooperation and goodwill while running the whole thing herself. She maintained that since she had originated the scheme, she was entitled to ten percent of the profits and not less than £500 in case of failure, believing that a premium should be put on her creativity in initiating the idea and her ability, through her contacts, to see it through.

As the tercentenary of Shakespeare’s death was approaching in 1916, various rival committees were being set up, each favouring their own pet scheme, which would serve as a suitable memorial. Some proposed the erection of a statue, others an ill-defined Shakespeare temple. Jennie was not the first to recognise the need for a National Theatre building in the capital linked to the country’s greatest dramatist—there had been one at Stratford, the Bard’s birthplace in Warwickshire, since 1879. But in those days, that was a rural outpost and far from London. It was Jennie’s brilliantly imaginative idea to create an event that would last several months and cater for the general public at popular prices to raise funds for a National Memorial Theatre, a modern-day theme park.

But although some of her friends kept restraining her, reminding her she must get estimates for the building works as well as for wages of the employees and performers, others led Jennie to believe that there was potential to make a lot of money, especially if the exhibition travelled to America with Jennie retaining an interest in it.

Taking it to America was a step beyond Jennie’s immediate thoughts. For the moment she needed to raise some £55,000 to build replicas of Tudor houses, the Globe Theatre, and the Mermaid Tavern, all designed by Lutyens. She approached wealthy friends and her own bank, Cox and Co, who, after serious investigations, agreed to back the project up to £35,000.

The exhibition opened with great élan and advertising; the side shows were interesting, the restaurants good, the sixteenth century dancing lively, and the orchestral concerts, under the conductorship of Sir Henry Wood, authentic. The Banqueting Hall, where “Queen Elizabeth” could be seen dining in state with her favourites and lovers, was imaginative and amusing. Yet in spite of all this, “Shakespeare’s England” flopped.

The highlight of the exhibition was a re-enactment of a medieval tournament held in the big hall, now laid out as a courtyard of a medieval castle. The jousting and revels were promised to rival the famous Eglington Tournament of 1839, while the costumes and armour of the competitors and the trappings of their horses would be historically accurate in the minutest detail. The entire scene was advertised as outdoing in splendour and magnificence the Field of the Cloth of Gold described in Henry VIII.

The newspapers all gave the tournament extensive coverage, but that event alone, hugely expensive to stage, could not prevent the exhibition losing money overall. It won her plaudits but no financial rewards and, finally, lost Jennie a husband. George, feeling excluded, maintained that far too much money had been lavished on the project, resulting in inevitable financial failure. Immediately after “Shakespeare’s England,” he gave up the marriage for good. Jennie, fifty-eight, told him she had “courage enough to fight my own battles in life,” and filed for divorce.

Old Curiosity Shops

There was one final approach to money-making which worked; she capitalised on her natural good taste and style to become what today would be called an interior decorator. Much of her advice was dispensed free to friends as she was still trying to earn money as a writer. But as she admitted to her nephew Shane, “I am disappointed that my contract with Harpers came to an end. It meant a good deal to me.” She sent him a collection of her recent articles written for Pearson’s Weekly, appealingly confusing her title “Great Talks on Small Subjects—no, Small Talks on Great Subjects.” And in 1916 Pearson’s also published Women’s War Work, a book that she edited and for which she wrote the preface.

In February 1921, Jennie managed to sell for £35,000 a house she had bought in Berkeley Square: “a clear profit of £15,000,” as Winston told Clemmie with undisguised relief. “She has already taken a little house in Charles Street. No need to go abroad. All is well. I am so glad.”

And so, in the spring of 1921, as Montagu Porch, a Nigerian-based civil servant who became her third husband in 1918, returned to Nigeria to explore investment opportunities there, Jennie went off to spend the profit from the sale of the house, staying with her old friend Vittoria Colonna, Duchess of Sermoneta, in Rome. The Palazzo Caetani, where Jennie had often stayed before the First World War, was being refurbished and Jennie was giving her friend advice on interior decoration. The two women enjoyed going to balls and shopping together: “we ransacked all the old curiosity shops and Jennie bought profusely; her zest in spending money was one of her charms.”

Among the items Jennie bought were some dainty slippers from the best Roman shoemakers—she always prized her slim ankles and kept her skirts short enough to display them. But wearing the new shoes (probably before her maid had scored the slippery soles) on a visit to her friend Lady Katharine Horner at Mells in Somerset, she fell down the staircase. What began as a sprained ankle quickly developed into gangrene, followed by amputation. On 29 June 1921, aged sixty-seven, Jennie died suddenly following a hæmorrhage. Like everything she did in her life, the leaving of it was highly charged and dramatic. Unprepared to the last, she died intestate.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.