Finest Hour 174

Churchill’s Empire DNA – Empire Man to Reluctant Commonwealth Man: A Canadian Perspective

December 12, 2016

Finest Hour 174, Autumn 2016

Page 06

By Terry Reardon

Terry Reardon is the author of Winston Churchill and Mackenzie King: So Similar and So Different (2012).

The Victorian era was the zenith of the British Empire. It was then the superpower of the world holding sway over 300 million people, one-quarter of the world’s population.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Winston Churchill was born into the upper class, and his formative years were steeped in the belief of the greatness and righteousness of the British Empire, upon which the sun never slept. This romantic view of Britain’s position in the world remained constant all through his life.

But being a member of the upper class did not necessarily mean an upper income, and it certainly did not in the case of Winston Churchill. Thus he took full advantage of the international reputation he had earned by way of his exploits and heroics in the Boer War by embarking on a lecture tour of Britain and then North America.

He arrived in New York on 8 December 1900 and spoke in ten cities. In the United States he had faced audiences often in sympathy with the Boers; thus he was relieved when he crossed the border into Canada, where he was greeted by enthusiastic throngs—he spoke in Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto on the theme “The War as I Saw It.” The Toronto Globe reported that every seat in the vast hall was occupied and that Churchill possessed a vein of humour, upon which he drew with excellent effect.

Churchill met with future Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King while in Ottawa, and the rather priggish King was not impressed with Churchill drinking champagne at 11 AM. Six years later they met again in London. King, then a senior civil servant, had crossed the Atlantic with the objective of having the British government enact legislation to curb false advertising to potential immigrants. King was not inclined to meet with Churchill in view of his previous experience, but since Churchill was Under Secretary of State for the Colonies he had no choice.

They met at a luncheon arranged by Sir Evelyn Wrench, the editor of The Spectator. Wrench recounted the event in his diary. He recorded that Churchill expressed support for the encouragement of British emigration to the colonies, with John Burns, President of the Local Government Board, responding, “Why would you wish to establish under the British flag replicas of Tooting around the seven seas?” According to Wrench, Churchill just “smiled benignly.”1

A Whole New World

The First World War changed the geography of the old world, with long established dynasties overthrown and young countries such as Canada rapidly coming of age. Canada’s contribution was staggering—out of a population of five million, 619,000 volunteered, 61,000 were killed, and 172,000 were wounded. While the strong attachment to Britain remained, it was now becoming more of an equal partnership—this was evident when Prime Minister Robert Borden insisted that Canada sign the Versailles Treaty separately from Britain.

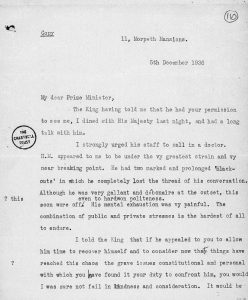

A further sign of independence came in 1922 and was triggered by an incident in the Chanak region of Turkey. Prime Minister Mackenzie King was asked by a reporter what would be his answer to Britain’s request for Canada to pledge troops for a possible action against the Turkish army. This was the first information that King had of the request, but he responded diplomatically that the Government would consider the matter. The procedure for communications between Britain and the Dominions involved routing through the British High Commissioner. This was a time-wasting process, and the British Colonial Minister, Churchill, had “jumped the gun” in advising the press.

The Chanak episode blew over, but it emphasized to King, anglophile though he was, that Canada could not continue in a subservient position. His first opportunity to redress the relationship came in the Imperial Conference of 1923—the British Foreign Minister, the highly articulate Lord Curzon, opened the Conference with a proposal that the British foreign minister should speak for all the Empire. King stated his position, which was that the Government of Canada would speak for itself. King eventually won the day, with the furious Curzon writing to his wife, “The obstacle has been Mackenzie King, the Canadian, who is both obstinate and stupid, and is nervously afraid of being turned out of his own Parliament when he gets back.”2

Three years later, at the 1926 Imperial Conference, King, abetted by South African Prime Minister James Hertzog, pushed for recognition of the Dominions’ independent status. This resulted in the Balfour Declaration, which stated that the Dominions “are autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, although united by a common allegiance to the Crown, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations.”3 Five years later the House of Commons debated the Statute of Westminster, which was to give formal recognition to the Balfour Declaration. Churchill, the first speaker on the bill, was opposed to changes, which he saw as diminishing the pre-eminence of Britain; but he was out of step with his parliamentary colleagues, and the bill was passed.

Into the Storm

Mackenzie King was a firm supporter of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in his appeasement policy of Germany, and he was suspicious and uncomfortable with Churchill’s many exhortations to the British Government to increase military expenditures to keep pace with those of Germany. In 1937 King met with Hitler in Berlin, with the Führer assuring King that “you need have no fear of war at the instance of Germany. We have no desire for war, and we don’t want war. Remember that I myself have been through a war. We know what a terrible thing war is and not one of us wants to see another war.”4

As we now know, Hitler was not being entirely dishonest—so long as he got what he wanted, there would be no war. King was obviously relieved by Hitler’s statement, but to his credit he stated that if Britain were attacked, Canada would come to Britain’s aid. Whether that made any impression on Hitler is not evident, but it certainly made no impact on his future decisions.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, the Canadian Parliament considered its position. The inter-war years had changed its relationship with Britain—in 1914 when Britain declared war Canada was automatically at war. Twenty-five years, later Canada’s parliament debated the matter and voted almost unanimously to join the conflict.

Canada’s neglect of its military needs in the 1930s saw it ill-prepared for war. But by extraordinary measures this was remedied, and the First Canadian Division sailed from Halifax, Nova Scotia, on 10 December 1939, with further troops transported over the next two months to increase the Canadian contingent to 23,000 soldiers.

Of crucial importance was the British Commonwealth Air Training Programme to train in Canada aircrew from Britain, Canada, and other Commonwealth countries. This achieved spectacular results, with 131,000 pilots and air crew trained at a total cost of $1.6 billion, Canada assuming three-quarters of that amount. In a letter to King on 1 January 1943, President Franklin Roosevelt referred to Canada as the “Aerodrome of Democracy.”5

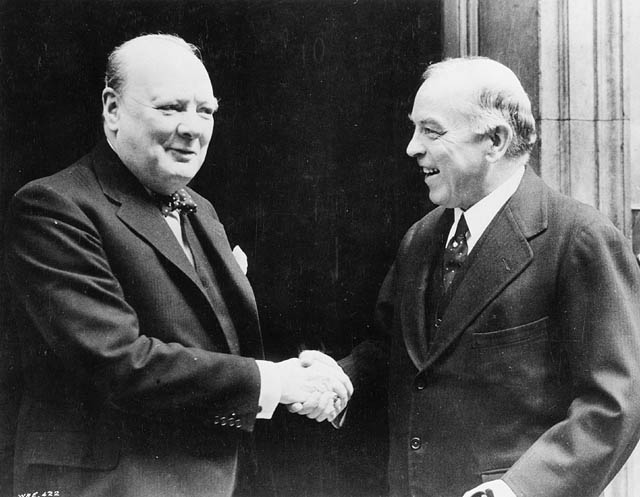

Churchill and Mackenzie King, London, 1941Finest Hours

Churchill and Mackenzie King, London, 1941Finest Hours

Although he had been highly critical towards Churchill in the past, King telegraphed to assure the full support of Canada when Churchill became prime minister in May 1940. These were not just empty words. British historian Richard Holmes notes that “in 1940–41 Britain would not have survived as an independent nation had it not been for the agricultural, industrial and financial aid received from Canada.”6

On 4 June 1940 Churchill made his famous “we shall fight on the beaches” speech. He talked of defending Britain and finished the sentence with “…if necessary for years, if necessary alone.”7 If he had been questioned on the “alone” he would undoubtedly have said that, of course, this included the countries of the Empire and the Dominions—the lack of clarification has been an irritant to many over the years, even accepting that the speech was composed at a highly stressful and crucial time in the war.

One year later, on 1 June 1941, Mackenzie King broadcast to the people of Britain and spoke directly to Churchill: “We have been inspired by your bravery, your undaunted courage and your determination to fight to the end.” King concluded: “To us you are the personification of Britain in this her greatest hour.”8

Churchill broadcast the next day to the people of Canada: “To Nazi tyrants and gangsters it must seem strange that Canada free from all compulsion and pressure, so many thousands of miles away should hasten forward into the van of the battle against the evil forces of the world….The people of Great Britain are proud of the fact that the liberty of thought and action they have won through their long romantic history should have taken root throughout the length and breadth of a continent from Halifax to Victoria.”9 High praise indeed—even though Churchill’s British, paternal attitude is evident!

With the United States in the war in December 1941, Churchill arrived to discuss strategy. On 30 December 1941 he spoke in the Canadian House of Commons. This included one of his best-known utterances. Referring to the French Government when it was considering an armistice with Germany in May 1940, Churchill stated: “When I warned them that Britain would fight on alone, their generals told their Prime Minister and his divided cabinet, ‘In three weeks England will have her neck rung like a chicken.’ Some chicken!” And, when the laughter of the MPs died down: “Some neck!”10 When Churchill left the House of Commons, he was photographed by Yousuf Karsh. The key image to emerge from the session became known as the Roaring Lion picture—the most famous photograph ever taken of Churchill.

While Churchill was appreciative of Canada’s significant contribution to the war, his attitude to the Dominions was still that it was a case of “The Tiger and Her Cubs.” This attitude was shared by the Americans. On 10 July 1943, Sicily was invaded. The communiqué included the “Forces of the United States and Britain.” Mackenzie King was highly indignant at the omission of the Canadian participants. His protests were ignored, and it took a direct appeal to President Roosevelt, before the announcement was changed to “British, American and Canadian troops….”11

In spite of this insult, the communiqué drafted for Eisenhower to announce the D-Day invasion in June 1944 referred to “British and American troops.” Again it required strong protests before the change was made to “American, British and Canadian troops.”12

A Sacred Mission

W ith the end of the war, Canada counted the cost. Out of a population of eleven million, more than one million voluntarily enlisted, 47,000 were killed, and 58,000 were wounded. The total expenditure in dollar terms was $18 billion. By the end of the war, Britain had received almost $3.5 billion in gifts and loans from Canada. In addition, Canada participated in a $5 billion loan in 1946 at a nominal interest rate of 2%—the United States lending $3.8 billion and Canada $1.2 billion. Much has been made of the major assistance given by the United States to Britain, but on a per capita basis, Canada gave more than three times as much.

After the war, Churchill had to accept the reality of the diminished role of Britain in the world, including its relationship with the Dominions and the few remaining countries still in the “Empire.” Britain had long since been replaced by the United States as Canada’s largest trading partner, although Churchill’s personal standing in the country, which he referred to as the Great Dominion, was undiminished.

In January 1952 he spoke in Ottawa. At a Parliamentary Press Gallery reception Churchill showed that he understood the changing relationship with the Dominions and could even bring humour into what most thought of as his anachronistic attitude. He stated: “The Canadian Press holds a high and distinguished place among the presses of what was once called the Empire. If that word slips out [laughter], I won’t ask your pardon.”13

Churchill’s speech included references to the wartime struggle and finished with an old favourite expression of his, referring to Canada’s linchpin role: “Upon the whole surface of the globe there is no more spacious and splendid domain open to the activity and genius of man, with one hand clasped in enduring friendship with the United States, and the other spread across the ocean both to Britain and France. You have a sacred mission to discharge. That you will be worthy of it, I do not doubt. God bless you all.”14

Churchill’s final visit to Canada was in June 1954, and he spoke to the country on the radio. After the radio broadcast Moran recorded, “…as his car drove off there was loud cheering and I could see that Winston was greatly moved….as the cheering grew in volume Winston perched himself out of his seat….there, with his hat in one hand, he held up the fingers of the other in the victory sign….in the air Winston kept talking of the kindly greeting the people of Ottawa had given him. ‘I purred like a cat,’ he said. ‘I liked it very much.’”15

Endnotes

1. Evelyn Wrench, Churchill by His Contemporaries, ed. Charles Eade (London: Hutchinson, 1954), p. 289.

2. R. MacGregor Dawson, William Lyon Mackenzie King: A Political Biography (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1958), p. 147.

3. Terry Reardon, Winston Churchill and Mackenzie King: So Similar, So Different (Toronto: Dundurn, 2012), p. 60.

4. Library and Archives Canada, The Diaries of Mackenzie King (Ottawa: On Line).

5. Lester B. Pearson, Mike, The Memoirs of the Rt. Hon. Lester B. Pearson, 2 vols. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972), vol. I, p. 208.

6. Richard Holmes, In the Footsteps of Churchill: A Study in Character (New York: Basic Books, 2005), p. 230.

7. Robert Rhodes James, ed. Churchill Speaks, 1897–1963: Collected Speeches in Peace & War (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1980), p. 713.

8. W. L. Mackenzie King MP, Canada at Britain’s Side (Toronto: Macmillan, 1941), pp. 277–78.

9. Winston S. Churchill, The Unrelenting Struggle (London: Cassell, 1942), p. 147.

10. James, Churchill Speaks, p. 788.

11. Reardon, Winston Churchill and Mackenzie King, p. 242.

12. Ibid., p. 280.

13. David Dilks, The Great Dominion: Winston Churchill in Canada, 1900–1954 (Toronto: Thomas Allen, 2005), p. 386.

14. Winston S. Churchill, Stemming the Tide (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1954), p. 219.

15. Lord Moran, Churchill Taken from the Diaries of Lord Moran (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966), pp. 606–07.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.