Finest Hour 193

Winston and the Welsh Wizard – Churchill and Lloyd George

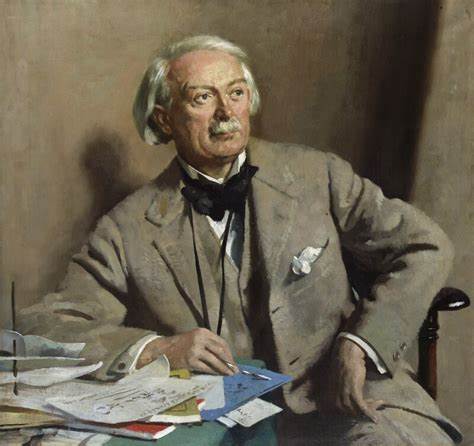

David Lloyd George

August 30, 2022

Finest Hour 193, Third Quarter 2021

Page 26

By John Campbell

John Campbell has written major studies of Lloyd George, Nye Bevan, Roy Jenkins, and others.

In his obituary tribute in the House of Commons in March 1945 Winston Churchill called David Lloyd George, with a typical historical flourish, “the greatest Welshman which that unconquerable race has produced since the age of the Tudors.” “When the English history of the first quarter of the twentieth century is written,” he concluded more specifically, “it will be seen that the greater part of our fortunes in peace and in war were shaped by this one man.”1

Today, of course, Churchill himself is consistently named both by historians and by the public as the “greatest Englishman” or the “greatest Briton.” But for years the two men who led the country to victory in the two global wars of the twentieth century were seen as equals. It used to be a favourite game of historians to debate which was the greater, however that might be defined. Today, though, Churchill’s reputation completely dwarfs that of his Welsh predecessor. This is largely because the Second World War is still endlessly celebrated in popular memory as Britain’s “Finest Hour,” and Churchill as the superhero who saved the world from Nazism, whereas 1914–18 has been written off as a futile and pointless bloodbath—as though it was not as necessary to resist German domination of Europe in 1914 as in 1939. In 1945 the cartoonist David Low drew Lloyd George and Pitt the Younger helping Churchill up beside them onto a plinth inscribed “Britain’s Greatest War Prime Minister.” But Lloyd George’s laurels have faded, leaving Churchill’s supremacy uncontested.

Contrasting Circumstances

Undoubtedly Churchill did surpass Lloyd George as a war leader in some respects. But this was largely because he enjoyed a much stronger position, politically and militarily, from which to direct strategy, whereas Lloyd George had to struggle to assert his authority over the generals. This in turn was because Churchill had Lloyd George’s experience in the previous war from which to learn. In 1916—and indeed in the earlier stages of the war, first as Chancellor and then as Minister of Munitions under Asquith—Lloyd George had to set up the whole war economy from scratch, in a country that had enjoyed a hundred years of peace. He had to create and energise the whole organisation of modern warfare with new ministries to direct labour, shipping, food production, and all the other structures of mass mobilisation, most of which had only to be reactivated in 1939. Dire though the military situation was in May 1940, it was arguably just as perilous when Lloyd George replaced Asquith in December 1916, with German U-boats inflicting heavy losses on shipping, food supplies down to a few weeks, and the nation already exhausted after two years of war and appalling sacrifice. Lloyd George quickly solved the shipping crisis by imposing the convoy system against the resistance of the Admiralty; and when he faced another crisis in the spring of 1918, when the Germans broke the stalemate on the western front and nearly broke through to Paris, the Prime Minister finally succeeded in securing Allied joint command, putting the British army under the ultimate command of the French general Ferdinand Foch. At least Lloyd George, unlike Churchill, had France as a powerful ally; on the other hand Churchill, from 1941, benefitted from the might of Russia draining Hitler’s strength in the east, whereas Russia had dropped out of the earlier war in 1917, allowing Germany to switch all her effort to the west. Both leaders were of course ultimately saved by the overwhelming force of the United States joining the conflict in 1917 and 1941.

2025 International Churchill Conference

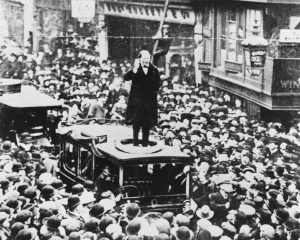

As a minister in various departments for most of the earlier war, Churchill had witnessed at first hand Lloyd George’s struggles to impose himself; and in 1940 he applied two specific lessons learned from Lloyd George’s example. First, from the moment he took office, Churchill appointed himself Minister of Defence so that he could personally command the military and direct strategy. Second, when Neville Chamberlain retired due to terminal illness in September 1940, Churchill ignored those who urged him to carry on as a national leader, above party, but insisted on being elected Conservative leader, so as not to be in Lloyd George’s position as a leader without a party. These two decisions account for the dominance he maintained over the next five years—even though the second did lead to his rejection by the electorate in 1945. Churchill also had the huge benefit of radio to broadcast his speeches. Comparing their techniques of leadership, it is remarkable that Lloyd George was able to lift morale and inspire the national effort without this means of direct communication, but solely by his speeches, reported in the newspapers and republished in book form. Both leaders commanded the House of Commons, but Lloyd George’s only national platform was the mass meeting.

Compared with Lloyd George, Churchill took little interest in plans for post-war reconstruction—he refused to be distracted by the Beveridge Report on welfare reform, for instance—whereas Lloyd George was always concerned that the immense sacrifices made by ordinary people during the war should be rewarded by improvements in their standard of living when it was over. Even as the Great War continued, Lloyd George’s government introduced the extension of national insurance, a major reform of education, and the extension of the franchise to all adult men and most women; and the Prime Minister promised more (“A fit country for heroes to live in”), though he was not able to deliver as much as he hoped because of the post-war recession and his dependence on the Tories.2

But this was because Lloyd George was much more than a war leader. In truth he should never have been a war leader at all. Whereas the Second World War was for Churchill the fulfilment of his destiny, the supreme crisis for which he had spent his whole life preparing, Lloyd George was diverted from what should have been his destiny as a radical domestic reformer, the role he had started to fulfil as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1908–14. The difference was clear in August 1914. Whereas Churchill loved war and could not deny that the prospect excited him in August 1914 (“I am interested, geared up and happy. Is it not horrible to be built like that?”3), Lloyd George hated it and was horrified at the prospect of having to support the war and then actively wage it:

I am moving through a nightmare world these days. I have fought hard for peace & succeeded so far in keeping the Cabinet out of it but I am driven to the conclusion that if the small nationality of Belgium is attacked by Germany all my traditions & even prejudices will be engaged on the side of war. I am filled with horror at the prospect. I am even more horrified that I should ever appear to have a share in it but I must bear my share of the ghastly burden though it scorches my flesh to do so.4

As it happened, Lloyd George grasped the scale of the national effort required earlier and was so much more energetic, inspiring, and motivating than anyone else in the government that he inevitably became Prime Minister when Asquith’s inadequacy could no longer be ignored.

Post-war Leaders

As war leader, Lloyd George led the country to victory—at terrible cost—in 1918; but his impact lasted well beyond the war. He transformed the office of Prime Minister and the whole machinery of government, introducing a new professionalism in place of the gentlemanly amateurism that had hitherto prevailed. He created the Cabinet Office, with a Cabinet Secretary taking and circulating proper minutes, where Asquith had merely written a letter to the King. He set up new ministries—of housing, shipping, labour, and health—most of which survived into the peace and extended the role of government into areas previously unimaginable. In his recent survey of the development of the office over three hundred years, Anthony Seldon ranks Lloyd George as one of only eight (out of fifty-five) “transformational” prime ministers (the others being Walpole, Pitt the Younger, Peel, Palmerston, Gladstone, Attlee, and Thatcher). Churchill does not make the list, quite rightly, because he did not leave a lasting legacy, apart from winning the war.5

After 1918 much of Lloyd George’s energy was diverted into making the peace and—with Georges Clemenceau and Woodrow Wilson—redrawing the map of Europe and the Middle East. It used to be held that the Treaty of Versailles led directly to Hitler and the Second World War, but, since Margaret Macmillan’s 2001 book Peacemakers, it is now generally recognised that they did not make such a bad job in very difficult circumstances. Whatever one’s view of that, the 1919 settlement in which Lloyd George played such a big hand unquestionably sowed the seeds of many of the difficulties the world still faces today in Israel, Palestine, Syria, Iraq, and the Balkans. Churchill was no longer in office to make the peace after 1945, but he was instrumental in drawing the post-war division of Europe with Stalin in 1944. As geopolitical peacemakers, neither Lloyd George nor Churchill can be judged wholly successful. On the other hand, if he did not finally resolve the eternal Irish Question, by the acceptance of partition and recognition of the independence of the Irish Republic in 1921, Lloyd George took the heat out of it for half a century. With the Montagu/Chelmsford reforms he also took the first cautious steps towards Indian independence, which Churchill furiously resisted.

Evolving Relationship

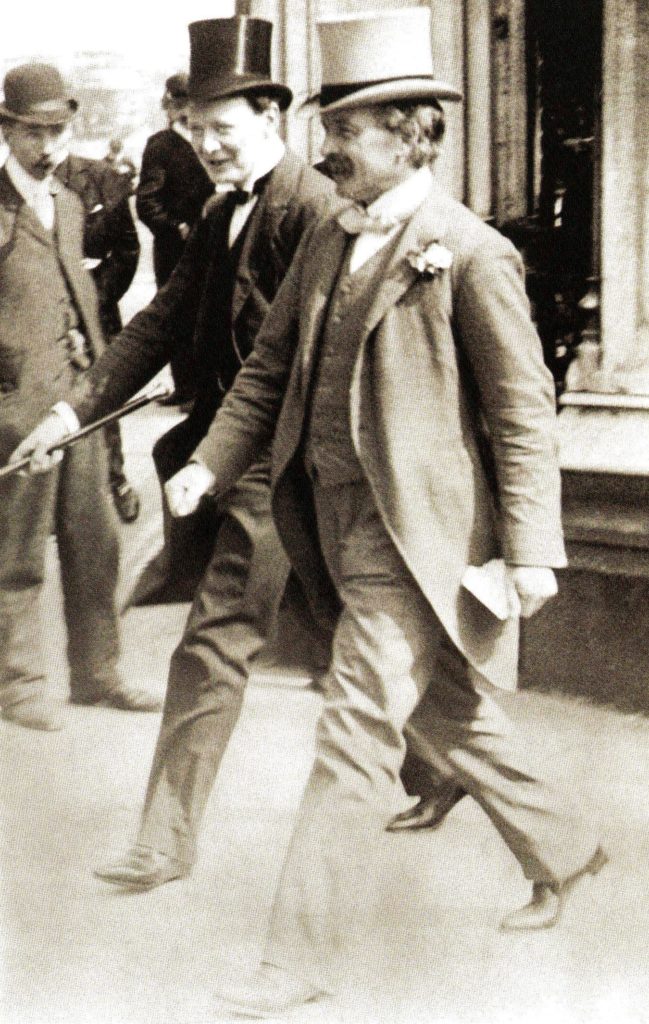

Churchill and Lloyd George were colleagues and rivals, sometimes allies and at other times opponents, for more than forty years. In public they always claimed to have enjoyed an unbroken friendship, but in reality they were often suspicious and derogatory about each other. Nevertheless they never lost a strong appreciation of each other’s exceptional qualities. The ups and downs of their long relationship can be traced through six distinct periods. At first, from around 1905 to about 1911, Churchill—eleven years younger than Lloyd George—was very much the junior partner, seeking Lloyd George’s advice before defecting to the Liberals and then, as President of the Board of Trade and Home Secretary, happy to work with him on his social reforms and echoing his rhetorical denunciations of the House of Lords in the constitutional crisis of 1911. At this time they were both regarded by the Conservatives as a pair of dangerous radicals.

From the moment Asquith moved him to the Admiralty in 1911, Churchill moved out of Lloyd George’s shadow, first in preparing for war—going head to head against the Chancellor for more money for the navy—and then, when war came, taking a bullish role in trying to direct it until he was undone by the Dardanelles debacle and dismissed from office in 1915 as the price of the Tories joining the government. Churchill thought that Lloyd George had not done enough to save him; but in the third phase it was Lloyd George, soon after becoming Prime Minister, who salvaged his career by bringing him back, first as Minister of Munitions and then, after the Armistice, as Secretary for War and Air, and Colonial Secretary—though Churchill was disappointed not to be made Chancellor. They had their differences in this period, notably over Churchill’s eagerness to support the White Russians against the Bolsheviks; but Churchill played a key role in the successful negotiation of the Irish Treaty in 1921.

After the fall of the coalition in 1922, their paths diverged again, as Churchill “reratted” back to the Tories and Lloyd George, in opposition, rediscovered his pre-war radicalism. Baldwin rewarded Churchill’s defection by making him Chancellor, in which role he was dismissive of Lloyd George’s proto-Keynesian plans to tackle unemployment by imaginative schemes of public works.

The 1930s found them both in the wilderness but still divided, despite occasional attempts to combine against the dull mediocrity of the National Government. They were on the same side in the Abdication crisis, both sympathising with the King’s wish to marry Wallis Simpson; but Lloyd George did not share Churchill’s obsession with blocking Indian independence and was slow to appreciate the need for rearmament against the threat of Nazism. His embarrassing flirtation with Hitler was short-lived, however; by 1939 he was convinced of the unavoidability of war and he played a dramatic part in forcing Chamberlain’s resignation in 1940, which paved the way for Churchill’s succession. But the final chapter was a sad one. Churchill wanted to bring Lloyd George into his War Cabinet, partly as a symbol of victory in the previous war but partly because he still admired his old colleague’s energy and motivating personality. But Lloyd George was now an old man; he was jealous of Churchill stealing his laurels and defeatist about the prospects of victory. He had a deluded idea that he should hold himself back to make a peace settlement when Churchill failed. (“I shall wait until Winston is bust.”6) The lowest point in their relationship came in May 1941 when Churchill in the House of Commons compared his old friend to Pétain.

But the reason Churchill wanted the seventy-seven-year-old Lloyd George in his War Cabinet in 1940 is that Lloyd George was the one figure in public life whom he always recognised as his equal, if not his superior. Violet Bonham Carter, Asquith’s daughter, who knew Churchill over his whole life better than anyone except Clementine, wrote after his death that Lloyd George’s “was the only personal leadership I have ever known Winston to accept unquestioningly in his whole political career.” Whereas their early partnership, in her view, “exercised no influence whatsoever on Lloyd George, politically or otherwise, it directed, shaped and coloured Winston Churchill’s mental attitude and his political course.”7 Robert Boothby, who served as Churchill’s PPS in the 1920s, recalled an occasion when Lloyd George came to see him in the Treasury. “Within five minutes,” Churchill told Boothby, “the old relationship between us was completely re-established. The relationship between Master and Servant. And I was the Servant.”8 He may not have meant it entirely literally, but Churchill would not have said it about anyone else.

Indispensable Men

Can we say which was the greater man? Obviously they both had their flaws. Both were ruthless, ambitious, self-centred and could be unscrupulous, but that is probably a condition of success in politics. In matters of personal morality, Lloyd George was a womaniser in his early life and effectively a bigamist in his later years, while Churchill was a faithful husband (though neither was a good father). Churchill was the indispensable man in 1940, and that is his undying glory. But Lloyd George was unquestionably the more skilful and effective peacetime politician and arguably the wiser statesman. As Churchill noted in his Commons tribute, he left his mark on every aspect of British life and government; the tragedy is that he could have achieved so much more had he not been diverted by the war, hijacked by the Tories between 1916 and 1922, and then excluded from a return to office by the rise of Labour and the first-past-the-post electoral system that consigned the Liberals to irrelevance. In the final reckoning Lloyd George too was the indispensable man at a moment of supreme crisis for the country; for that he deserves to share with Churchill the laurels of the Greatest Briton.

Endnotes

1. Speech in the House of Commons, 28 March 1945.

2. Speech at Wolverhampton, 24 November 1918.

3. Mary Soames, ed., Winston and Clementine (London: Doubleday, 1998), p. 96.

4. Kenneth O. Morgan, ed., Lloyd George: Family Letters (Cardiff: University of Wales, 1973), p. 167.

5. Anthony Seldon, The Impossible Office: The History of the British Prime Minister (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), pp. 95–135.

6. Colin Cross, ed., Life with Lloyd George: The Diary of A. J. Sylvester, 1931–45 (London: Macmillan, 1975), p. 279.

7. Violet Bonham Carter, Winston Churchill as I Knew Him (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1965), p. 161.

8. Robert Boothby, Recollections of a Rebel (London: Hutchinson, 1978), pp. 51–52.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.