Finest Hour 171

The River War: Preparing the Definitive Edition

March 8, 2016

Finest Hour 171, Winter 2016

Page 10

By James W. Muller

The Discovery

The Discovery

It was a grey day in January 1989 when I discovered that my leather-bound copy of The River War, one of thirty-four volumes of the Collected Works of Sir Winston S. Churchill that I had recently purchased, was but an abridgment. Like Churchill himself, if on a more modest scale, I have always lived a charmed life; and, by extraordinary good fortune, my wife Judith and I were halfway through a fifteen-month wedding trip, for most of which we lived in civilized but straitened splendor in London at William Goodenough College, near Russell Square. I was an academic visitor at the London School of Economics and Political Science, working on a book about Churchill’s writings. But half a dozen noble distractions—books on and by Churchill that I have been editing since then—are my apology for my original work remaining incomplete more than a quarter-century later. Four of these distractions have been published, with two more soon to appear: new editions of Churchill’s autobiography My Early Life: A Roving Commission and his most impressive early book The River War: An Historical Account of the reconquest of the Soudan.

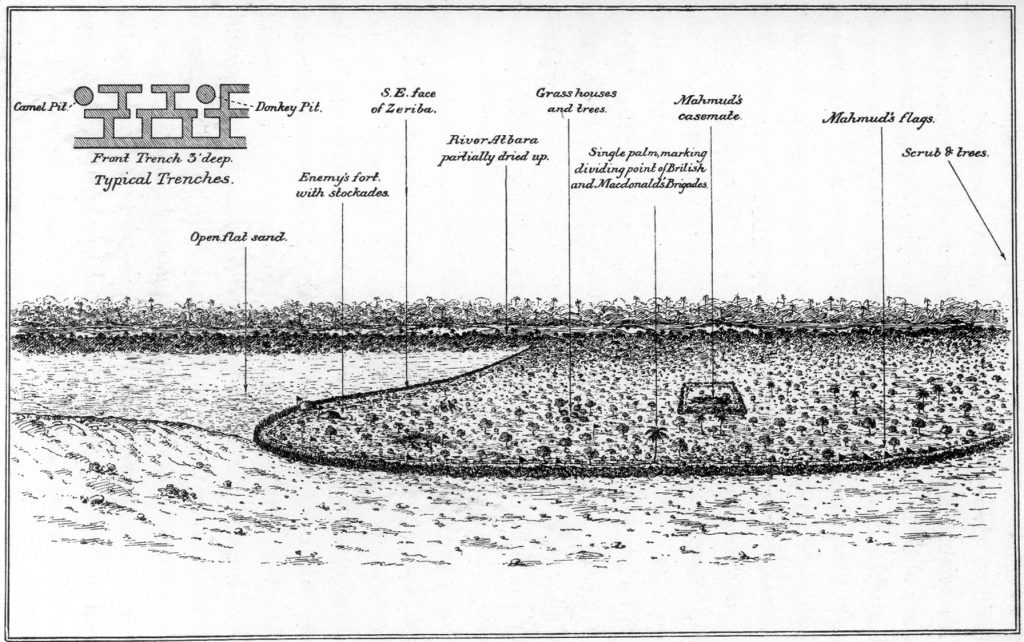

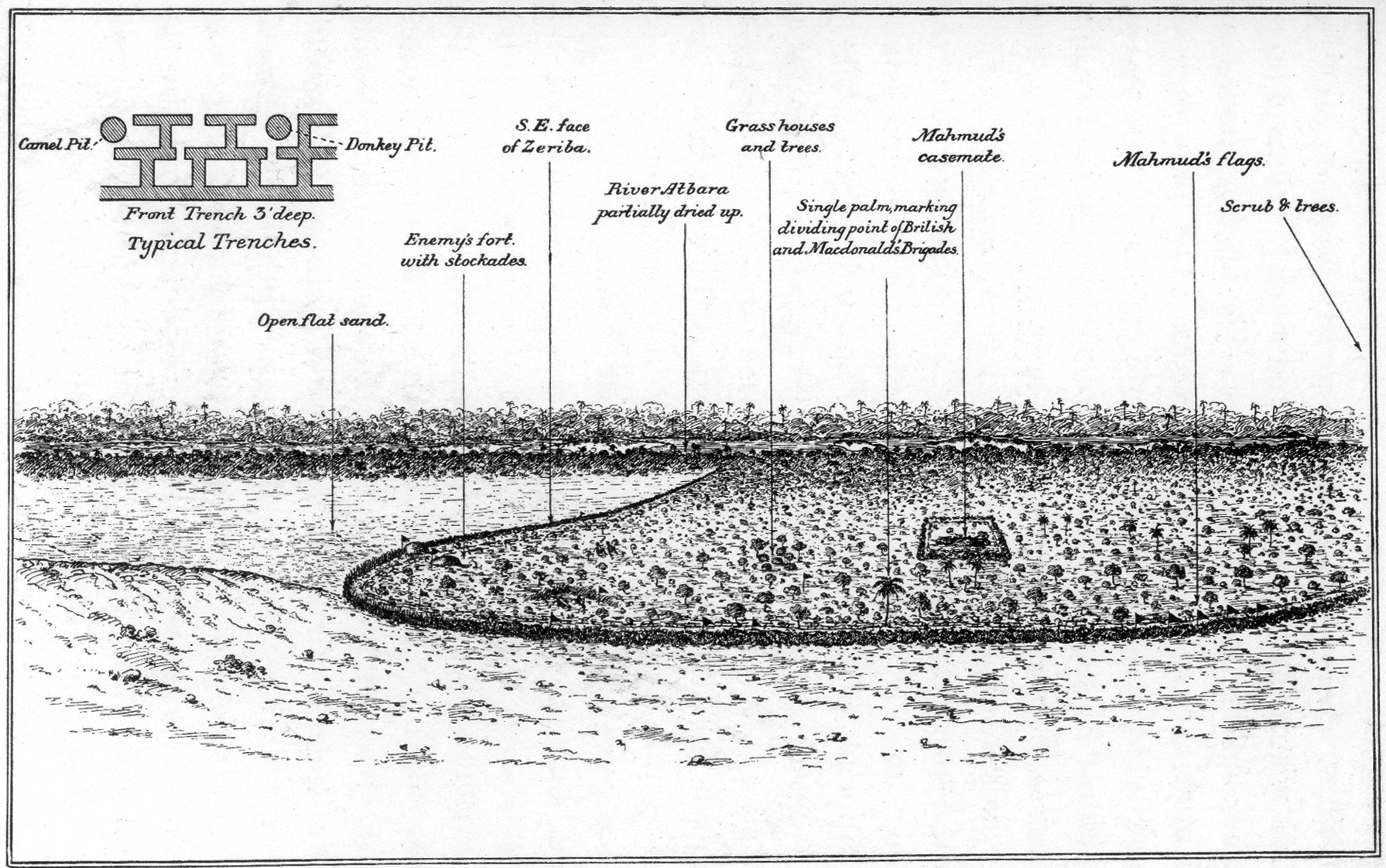

Having just finished in autumn 1988a draft chapter about Churchill’s experiences on the Nile nine decades earlier, I was learning that winter about his time in South Africa. But an entry in the bound catalogue of the old British Library stating that the first edition of The River War, published in November 1899, was a two-volume work had led me to look at it. A rare book, it had to be consulted not at my usual seat in the round Reading Room, where Karl Marx had written his book on capital, but in the North Reading Room, where rules were stricter. After the book was delivered to me there, I kept it for days to find out what the differences were between it and the version I owned. It turned out that the first edition had seven chapters, passages in all other chapters, three appendices, and many maps and illustrations that were left out of later editions. By the end of the month I realized that The River War was a much richer, more intriguing book than I had known from reading the shorter version.

The Idea

The Idea

Since the attack on New York’s World Trade Center on 11 September 2001, a quotation has flown round the Internet—a memorable pronouncement by Churchill about Islam, from the first edition of The River War, which cannot be found in any edition readily available today. It causes confusion when readers search for it in vain in shorter editions, because it is among the hundreds of passages in the first edition that were left out of the second. The importance of the changes and the rarity of both editions persuaded me that a new definitive edition of The River War was needed—one that restored the original text but also showed subsequent alterations.

Before long, my friend Paul A. Rahe, an historian then at the University of Tulsa and now at Hillsdale College, who wrote a fine chapter on The River War for my book Churchill as Peacemaker (1997), urged me to take up this work in succession to Cecil Rhodes’s brother Colonel Frank Rhodes, the original editor of Churchill’s book. My fellow governors of the Churchill Centre were enthusiastic about the project. Richard M. Langworth, then President of the Centre, invested his formidable energy and imagination in launching it, sharing his deep knowledge of all matters related to Churchill and, with his wife Barbara, welcoming me on visits to his voluminous library in New Hampshire. Parker H. Lee III, then Executive Director of the Churchill Centre, supported my work and, eventually, with the help of Anthea Morton-Saner at Churchill’s literary agency Curtis Brown, drew up the contract for this new edition, which has since claimed attention from her successor Gordon Wise. Subsequent presidents of the Churchill Centre John Plumpton, William C. Ives, and Laurence Geller also gave the project enthusiastic support, as did Administrator Lorraine Horn and Executive Directors Daniel N. Myers and Lee Pollock. The new edition is to be published this year in two volumes by Bruce Fingerhut at St. Augustine’s Press, who has been steady, perceptive, and game in returning the book to print.

2024 International Churchill Conference

The Task

The Task

The Churchill Archives Centre, where I was a by-fellow in fall 1995, houses Churchill’s papers, an inexhaustible collection of wonders. Its director, Allen Packwood, has been a stalwart supporter of my work on this book, together with his staff, just as his predecessor Piers Brendon has been. But neither at the Churchill Archives nor anywhere else have I found, in more than two decades since then, marked-up drafts of the first edition, showing passages to be dropped in the second edition, published in 1902, which became the basis for all subsequent editions, including the one I had used to write my chapter. The brief introduction to The River War in the Collected Works by Churchill’s bibliographer Frederick Woods breathes not a word about the fact that it was abridged. Many distinguished authors of books on Churchill are as unaware of the existence of the longer edition as I had been. But in the second edition, which is even rarer than the first, I found a brief explanation in Churchill’s new preface, dropped in subsequent editions, of the need to reduce the length of the book to make it fit into a single, cheaper volume.

Larry S. Arnn, then President of the Claremont Institute and now President of Hillsdale College, arranged for Thomas and Lori Krannawitter, Leah Conger, and Jeffrey Hall to scan two editions of The River War provided by Churchill bookseller Mark Weber. The old-fashioned typography left scans riddled with gibberish; my consolation for spending hundreds of hours correcting the text was that it was easier than typing every word of a book that ran to almost a thousand pages in the original edition. Mark answered my bibliographical inquiries and dozens of questions about variants, provided me with Churchill’s articles in periodicals, lent me (and subsequently the publisher) a copy of the first edition, helped me to locate other editions of the book, and, with his wife Avril, hosted me in Tucson during a visit to consult his massive stock of Churchill books.

To get to the bottom of the internal evidence about the changes made in revising The River War was one of the main reasons I took on this project. Denali Kemppel, then a student at Dartmouth College, assisted me in collating texts of different editions, with support from a grant by the Æquus Institute. I compared the first edition with the 1902 revision, marking differences for the new edition, which includes the whole text from both editions and will be printed in two colors with new footnotes so the reader can follow the changes. Students at the University of Alaska, Anchorage, especially Anastasia Mironova and Olga Bochkaryova, helped me proofread and establish the text of the new edition, making sure every word and punctuation mark is taken accurately from earlier editions of Churchill’s book.

Twists and Turns

The 1996–99 centenary of what our author called the River War, just before the turn of our new century, would have been an auspicious moment for publishing a new edition, but mine was far from ready then. Another edition appeared in 1997, introduced by the author’s homonymous grandson the late Winston S. Churchill, taking its text from a 1962 abridgment of the shorter version of The River War. The delay allowed me to profit from a steady trickle of new books about the campaign. One of them informed me that some fifty illustrations drawn for the first edition of The River War by Churchill’s brother officer and fellow Harrovian Angus McNeill but dropped from the book thereafter were still extant in the artist’s family. By the generosity of his granddaughter Sheila Fanshawe, they will be restored in the new edition, along with many colored maps that were dropped from the book after its first or second editions.

From another centenary book I learned that fourteen of Churchill’s fifteen handwritten dispatches for the Morning Post from the Sudan in the summer of 1898, his raw material and first draft for parts of the book, had come to light in the papers of the newspaper’s proprietor in the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds. Happening to be in London, I left the British Library, which by then had moved to new quarters near King’s Cross, and boarded a train to Leeds to read those dispatches, not knowing that Leeds was three hours away. After returning to London the same evening to retrieve my suitcase, I took a second trip to Leeds. Three days later, I had transcribed the whole text of the dispatches as Churchill originally wrote them, in a form quite different from the sanitized, shortened version published in the Morning Post and afterwards reprinted in books of Churchill’s early war dispatches. Later, my student Elizabeth Heim helped me decipher Churchill’s handwriting and compare it to his newspaper columns I had photocopied at the British Library newspaper archive. A new edition of the dispatches, which have never before been printed as Churchill wrote them, with notes indicating revisions made by the newspaper editor, will appear as a new appendix in the second volume—an intriguing element of the new edition.

I began to teach seminars on The River War to students at the University of Alaska, Anchorage, and their questions about personalities and events of a faraway campaign in the desert more than a hundred years earlier persuaded me to add more new footnotes. I resolved to identify, as far as possible, every person mentioned in the twenty-six chapters of the book, every passage quoted or referred to by Churchill, and terms and events that might be unfamiliar to the twenty-first century reader. This detective work, begun in the earliest days of the Internet but powerfully assisted over time by its increasing richness, which provided many good leads, has been among the most rewarding parts of the project. I have profited from countless books and articles chased down by indefatigable reference and interlibrary loan librarians.

Debts of Honor

The official Churchill biography by Sir Martin Gilbert answered many questions and provided clues for further research, which Martin encouraged at our meetings in London and Alaska. I had the new Churchill bibliography by Ronald I. Cohen always at hand, and its author provided advice and encouragement at all stages of the project. I had help from experts on the Sudan, such as the late Professor Robert Collins at the University of California, Santa Barbara. For biographical footnotes on Sudanese figures I also relied, with permission from his publisher, on the excellent biographical dictionary by the late Richard Hill. I made several visits to the Sudan Archive at the University of Durham, whose director Jane Hogan was unfailingly helpful. One of my students, Margaret Miller, née Dewhurst, made a separate trip thither to help with research. Douglas S. Russell, a fellow governor of the Churchill Centre and author of a book on Churchill’s career at arms, answered questions and shared bibliographic discoveries with me.

Before the turn of the new century, I befriended Lieutenant Colonel Paul H. Courtenay, formerly of The Royal Sussex Regiment and The Queen’s Regiment, who has for years done yeoman service as senior editor of Finest Hour. No one knows more about British military and court history than he does or is better informed about things in Britain that puzzle Americans. Not only has he read every word of the new edition and contributed to more wonderful footnotes than I can count: he has also enlisted assistance from friends who have lived in the Sudan, especially Henry Keown-Boyd, author of several books on the Sudan campaign, and Colonel Anthony C. Uloth, who served as Defense and Military Attaché at the British Embassy in Khartoum in the early 1970s. In addition to conversations at his house in Hampshire, at Blenheim Palace, in Anchorage, and at International Churchill Conferences over the years, we visited together such places as the Museum of the Corps of Royal Engineers, Chatham, to see the copper emblem from the tomb of the Mahdi and a statue of Gordon, and the Museum of the Queen’s Royal Lancers, then at Belvoir Castle but since 2007 in Thoresby Park (near Newark), whose exhibits show the history of the 21st Lancers, including the trumpet that blew the charge at the Battle of Omdurman on 2 September 1898.

Several years ago typesetting of the new edition began, carried out by a firm called Datapage in Bangalore, India, where the young Churchill served before and after his participation in the Sudan campaign, while his regiment was stationed in India. The complicated typography has made typesetting protracted, with thousands of change orders passing back and forth between Anchorage and Bangalore.

I am grateful to Sir Winston’s daughter the late Lady Soames for her example as a writer, for conversations about her father, for encouragement and good counsel throughout my work on The River War, and for writing a new foreword to my edition.

Finally, I salute my wife Judith, who has encouraged my work on The River War for the whole of our married life, and our daughter Helen, who has done likewise all her life and has also helped with proofreading; those who helped put together two volumes worthy of Churchill’s work; and all eager would-be readers of this new edition known and unknown to me, including some now sadly deceased, who have looked forward so patiently to its completion.

James W. Muller is Professor of Political Science at the University of Alaska, Anchorage, where he has taught since 1983, and Academic Chairman of The Churchill Centre. He is editor of the definitive edition of Winston Spencer Churchill, The River War: An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan, to be published in two volumes later this year by St. Augustine’s Press in association with the Churchill Centre.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.