Finest Hour 192

Observing “Churchill at the Helm”

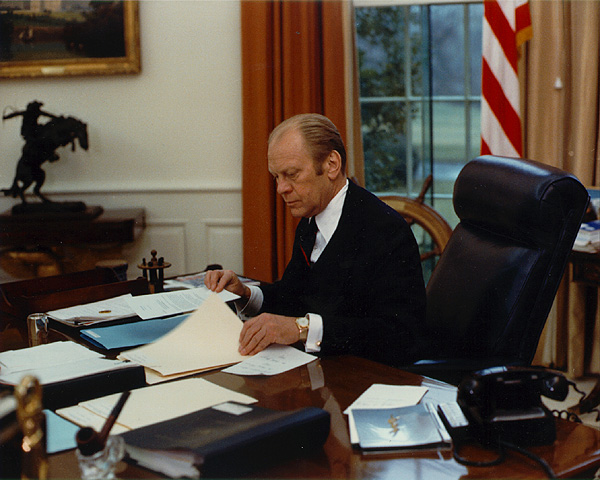

President Ford at work in the Oval Office.

December 15, 2021

Finest Hour 192, Second Quarter 2021

Page 34

By Gerald R. Ford

The International Churchill Society is grateful to Stacy Davis of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for bringing this document to our attention. It has never before been reproduced in print. The original document may be viewed online at: https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/document/0054/4525435.pdf

In January 1952, Winston Churchill travelled to Washington to meet with President Harry S. Truman. During his stay, Churchill was invited to be a guest in the gallery when the President delivered his annual State of the Union address to Congress. A few days later on 17 January 1952, Churchill himself spoke to the United States Congress for the third and final time. In the audience on both occasions was thirty-eight-year-old Gerald R. Ford (1913–2006), who was starting his fourth year as a member of the House of Representatives. One week later, the future thirty-eighth President of the United States (1974–77), sent this detailed account of Churchill’s appearances to his Michigan constituents.

State of the Union

The joint session of the Congress on this occasion was unusual because Winston Churchill sat in the gallery along with hundreds of others to listen to the President’s address. Mrs. Truman sat on the right of Mr. Churchill and Anthony Eden, the British Foreign Minister, on his left. When the Prime Minister entered the House Gallery he was given a very spontaneous ovation, and in the typical “Winnie” fashion he gave a most polite bow with gestures. It was interesting to note that Mr. Churchill, during the President’s address, read a copy rather than listened. On January 17th the Prime Minister will return to the House of Representatives to make an address of his own. The contrast between “H.S.T.” and “Winnie” will be interesting to observe.

Churchill’s Final Speech to Congress

Last week Winston Churchill made his third address in a decade to a joint session of the Congress. It is my recollection the two others were made while I was overseas with the Navy in World War II. On his third appearance in the House Chamber I had a reasonably good seat just behind the berobed Justices of the Supreme Court and a few rows of Senators. This was close enough to observe him carefully, watch his unusual mannerisms and feel his impact on the audience.

What was my reaction? One should divide the answer in two parts. First, what was the effect of his appearance and his method of speaking. Second, what of the content of his remarks.

The Churchill appearance and manner of speaking fell below the standard set by General Douglas MacArthur. Undoubtedly the setting for the Prime Minister wasn’t as dramatic as the occasion when General MacArthur appeared before the House and Senate last spring. Yet I looked forward to a Churchillian gem and somehow it wasn’t quite up to expectations. It surpassed President Truman’s best but then the President isn’t much of an orator. Somehow there was a hope Mr. Churchill would deliver another “blood, sweat and tears” speech. Instead the Prime Minister stuck precisely to his prepared text. Obviously this restriction cramped his oratorical style. Nevertheless it was a real treat to see and hear this great statesman who represents our staunch British friends. The audience in the House Chamber, before, during and after his address, warmly applauded this resolute leader of 77 years. The ovations were richly deserved.

The Prime Minister got off on the right foot in his speech when he said, “I have not come here to ask you for money.” At this point he was interrupted by applause. He struck another responsive note when tribute was paid to the late Senator Vandenberg of Michigan.

There was the usual pomp and ceremony customary to such occasions. There were eight Justices of the Supreme Court with only Justice Black absent. The diplomatic representatives of most nations were present. However, no emissary of Soviet Russia was in the group. Any representative of Stalin would have been more than slightly embarrassed by Mr. Churchill’s remarks. The members of the President’s cabinet also occupied reserved seats in the well of the House Chamber. Mr. Truman was absent. It was reported he watched the speech from a television set in his office.

The speech, or its content, was impressive. Mr. Churchill believes the United States, Great Britain and their allies can ward off a third global war by accumulating atomic weapons and other deterrents to aggression. The Prime Minister described America’s atomic bomb as the supreme deterrent and most effective guarantee of victory but warned the United States “not to let go of the atomic weapon until you are sure—and more than sure—that other means of preserving peace are in your hands.”

Mr. Churchill asserted he was here to ask, “not for gold but for steel, not for favors, but for equipment” to help in the British rearmament program. He convincingly stressed the importance of American-British cooperation in meeting problems around the world and declared our two countries now “are working together for the same high cause.”

Some vital questions were left unanswered but after all not every knotty issue can be resolved in a 35-minute speech. Mr. Churchill could have cemented American-British ties by announcing that Great Britain was dropping its official recognition of Red China. It was evident, however, the English patience was being strained by the policies of the Chinese Communists. In addition, most Americans would have felt better if there had been a little more “give” by the British on the issue of European Federation. There was a pledge by England to help European unity but one wonders if that can be attained with Great Britain remaining a bit standoffish.

When it was all over I walked back to the House Office Building with several other Congressmen, both Democrat and Republican. It was the consensus that Mr. Churchill had done a far better job of tying up American-British unity than could have been done by the preceding Prime Minister, Clement Attlee of the Labor government. Somehow one feels a greater strength in the British government with Winston Churchill at the helm.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.