Finest Hour 190

Death to the French

January 1, 1970

Finest Hour 190, Fourth Quarter 2020

Page 37

By David Freeman

David Freeman is editor of Finest Hour.

Winston Churchill loved to read. He grew up in the Victorian Age when books did not have to compete for attention with any form of electronic entertainment. Not afforded the opportunity of a university education, he sought to fill the gaps in his knowledge through a rigorous program of reading while serving as a young cavalry officer in India.

At the start of Churchill’s political career in the Edwardian era, the bachelor MP opened accounts with London’s leading booksellers. We know something of Churchill’s tastes in reading from the purchase records that survive in the Churchill Archives at Cambridge. History, mostly political and military, features in orders, but he also kept up with contemporary fiction, including the works of H. G. Wells. What we do not always know for certain, however, is just which books he read.

Like many avid readers, Churchill bought more books than he could ever get through. Yet books always make handsome decorative features in any home. “Nothing makes a man more reverent than a library,” Churchill wrote in middle age when he had clearly come to realize that he would never read all of the books that he possessed. “Think of the mighty labours which have been accomplished for your service,” he continued, while contemplating all of the books available to be read, “but of which you will never reap the harvest.”1

2025 International Churchill Conference

Authors We Know

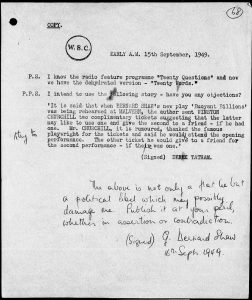

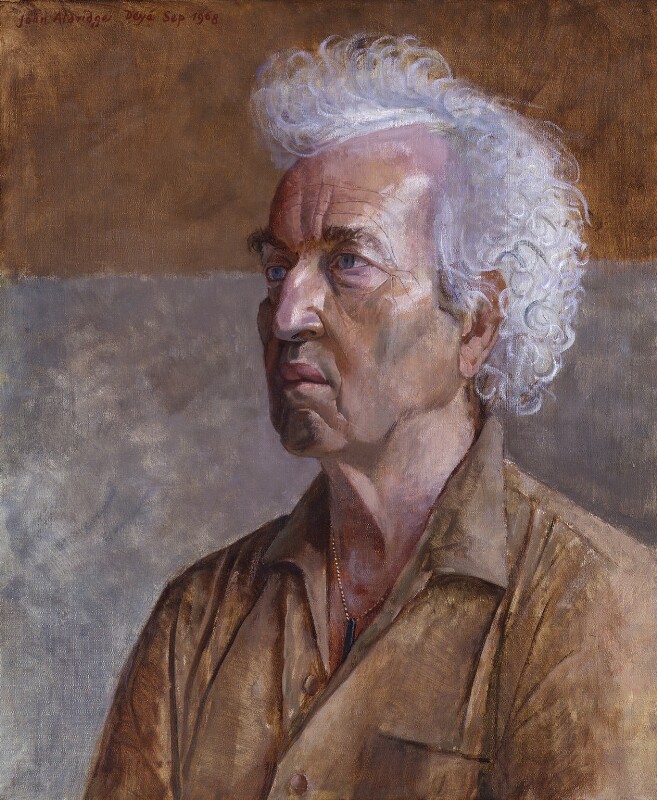

While purchasing does not always lead to reading, we do have some idea of which books Churchill did read and enjoy as a result of encounters he had with their authors. We are reminded in this issue of Finest Hour of meetings Churchill had with Mark Twain, George Bernard Shaw, and Siegfried Sassoon. He had Twain sign copies of twenty-five different books, he attended Shaw’s plays, and he memorized Sassoon’s poetry.

Our knowledge of what Churchill read increases substantially in his later years when his station in life had become such that people around him made a point of documenting what they observed him reading. “He liked autobiographies,” remembered his nurse, Roy Howells, who recorded that among Churchill’s favorite novelists were “Somerset Maugham, Rudyard Kipling, Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson.”2 Late in their lives, Churchill and Maugham enjoyed lunching

together in the south of France.

Churchill “sometimes read books that he himself had written,” Howells noted. “I do not remember him ever reading mysteries or detective stories, at least not modern ones,” Howells continued, “although he did read Witness for the Prosecution after seeing the film.”3

Churchill also made good use of public libraries. Either the library staff or his own secretaries, knowing his tastes, would bring him a selection to choose from, and typically he would read about half of them. “Most of his reading was done either in bed or in the drawing room,” Howells remembered, “and after reaching the end of a book he would hand it to me saying, ‘I don’t want to see his face again!’ He often referred to objects as ‘he.’”4

“Have You Read It?”

Sometimes it happened that authors sent Churchill their books. Robert Graves was a favorite of Churchill’s, who wrote about his experiences serving with the Royal Welch Fusiliers during the First World War in the classic memoir Goodbye to All That. At the end of the Second World War, Graves published his novelized version of the quest for The Golden Fleece and sent Churchill a signed copy. Churchill read it while in Italy during his first post-war holiday. “It is the stiffest of all your books,” Churchill wrote Graves, “but once it gets hold of you, you cannot put it down….For this I am indeed grateful.”5 Churchill would later enjoy Graves’s I Claudius (“which is very readable,” he told his wife), Claudius the God, and Count Belisarius.6

Churchill had a special connection to another contemporary classic. “Found the P.M. absorbed in George Orwell’s book, 1984,” recorded his doctor, Lord Moran, in February 1953. “Have you read it, Charles? Oh you must. I’m reading it for a second time. It is a very remarkable book.”7 The novel’s protagonist, the doomed Winston Smith, had been named by Orwell after Britain’s most famous living politician. On the Beach by Neville Shute was another apocalyptic novel of the time that Churchill read twice.

Female novelists did not go neglected by Churchill. Jane Austen’s Persuasion and Northanger Abbey appear on a list of books he took with him on a cruise late in life aboard Christina, the luxury yacht of his friend Aristotle Onassis. Jane Eyre he loved, finding it so arresting that he stayed up reading Charlotte Brontë’s masterpiece until two o’clock in the morning. “It is a wonderful book,” Churchill told Moran, “I am so glad I have read it.”8 His verdict on Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, however, was much different: “I find it difficult to follow—rather confused.”9 The confusion, however, may not have been due to the author.

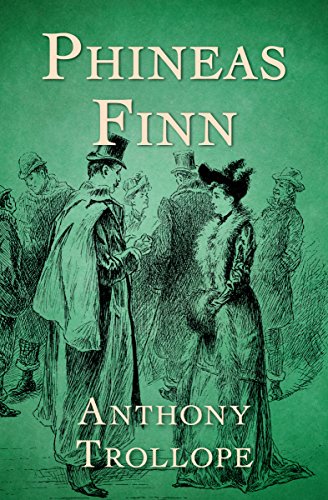

Phineas Finn to the Rescue!

Churchill had discovered the Brontë sisters late in life while recovering from a major stroke in the summer of 1953. “Funny that my education in Victorian novels should begin when I am nearly eighty,” he told Moran.10 He suddenly developed an all-absorbing passion for the Palliser novels of Anthony Trollope. These six books trace an imaginary set of characters through the political world of Victorian Britain.

The only thing surprising about Churchill’s reading of Trollope is that it came so late in his life. As a boy he closely followed the political careers of his grandfather, who served under Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, and his father, a mercurial politician of the mid-1880s. When Lord Moran found Churchill reading a biography of Disraeli, he ventured to say, “It must be heavy going, old politics?” “I like old politics,” Churchill growled.11

However late Churchill’s discovery of Trollope’s fictionalized account of the Victorian political world, the timing proved fortuitous. After his stroke, he needed a tonic. The Palliser novels gripped him completely. Even though he could not get out of bed before lunchtime or have the strength to turn the pages of a book, a solution was found. Jane Williams, one of Churchill’s secretaries at the time recalls: “Jock Colville [the Private Secretary] and I set up a reading table for him on his bed. One of us would sit by his side, and, when he came to the end of a page, he would close his eyes and we would turn the page for him.” “He would continue in this way,” Lady Williams recalls, “totally immersed for one to two hours.”12

Churchill was still Prime Minister at the time, and his Red Boxes of official documents would be sent down from Downing Street to Chartwell, where he was convalescing. His obsession with Trollope, however, meant the boxes often went unattended. “I can remember the papers piling up,” Lady Williams recalls, and Lady Churchill exclaiming, “Winston has fallen in love with Phineas Finn!”13 Finn is a title character in one of the Palliser novels.

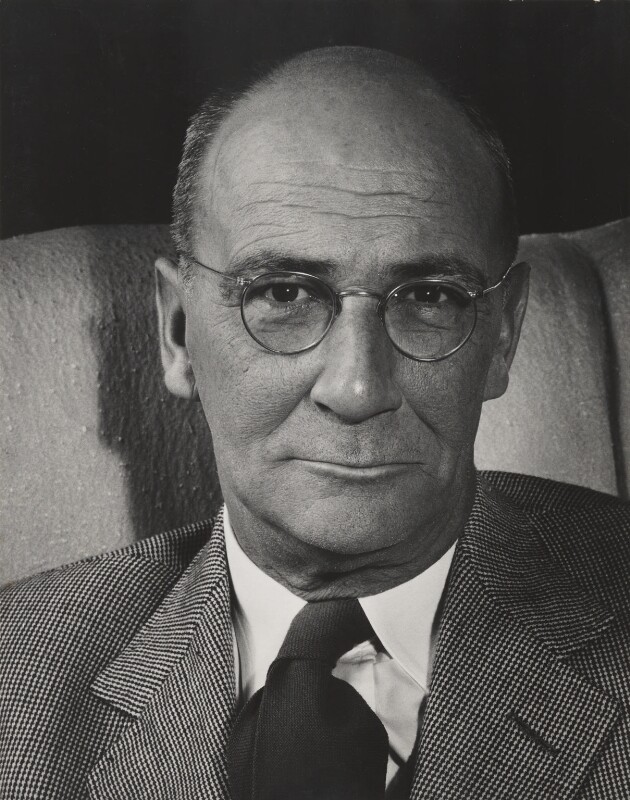

C. S. Forester

Of all the contemporary authors that Churchill read, C. S. Forester appears to have been the one he enjoyed the most over an extended period of time. Cecil Louis Troughton Smith was born in Cairo in 1899. He grew up in London and attended Dulwich College, which had been founded by a member of Shakespeare’s company and counts among its alumni P. G. Wodehouse and Raymond Chandler. Smith’s poor eyesight prevented him from serving in the First World War. Instead he appended Forester to his first and last initials to create his pen name and fought his battles on paper.

Forester wrote prodigiously, but his most popular books—the ones that are still in print—all revolve around imaginary military figures in historic conflicts. The heroes are model soldiers and sailors who persevere in the face of adversity. The General (1936) tells the story of a man who, like Churchill, went to Sandhurst to become a cavalry officer in the late Victorian period and served with distinction in the Boer War. During the Great War, he is rapidly elevated to the rank of Lieutenant General and thrust into the horrors of the Western Front. The Good Shepherd (1955), the basis for this year’s film Greyhound starring Tom Hanks, is a fast-paced story about a US Navy commander escorting a convoy across the Atlantic during the Second World War.

The African Queen (1935) was adapted into an enormously popular film in 1951 with Humphrey Bogart and Katherine Hepburn improbably cast as British civilians trapped in central Africa by the events of the First World War. The film delivers a much different ending from Forester’s novel, which—in proper Foresterian fashion—has the dreaded German gunboat sunk by the actions of the Royal Navy and not the book’s protagonists.

Hornblower

Forester’s most famous creation of all remains Horatio Hornblower. Originally intended as a one-off, the first Hornblower novel came out in 1937 and told the story of a Royal Navy captain on an unusual mission to Central America during the Napoleonic Wars in 1808. The book sold well enough that Forester continued Hornblower’s story from that point and eventually started writing novels about Hornblower’s early career, starting with his days as a midshipman. By that time, Forester had settled permanently in California, having gone to the United States during the Second World War to write propaganda on behalf of the British Ministry of Information.

“It was partly because of the accurate historical allusions they always contained,” Churchill’s bodyguard Edmund Murray wrote, that Churchill “would devour each of C. S. Forester’s Captain Hornblower stories as soon as he laid hands on it.” Churchill “was such a devotee of the celebrated Captain,” Murray continued, “that Forester would send him, from his home in America, an autographed copy of each new work.” “When the author came to visit England,” Murray concludes, “he was invited to Chartwell for lunch.”14

Forester had published three Hornblower novels by the time the Second World War began. Churchill remembered that he had little time for pleasure reading during the first two years of the conflict. When he set off across the Atlantic in August 1941 for his first wartime meeting with President Roosevelt, however, Churchill had several days journey on the battleship HMS Prince of Wales. It is at this point that Forester’s books start to appear in Churchill’s story. “A comparatively idle day,” Private Secretary John Martin wrote in his diary at sea, “PM reading ‘Hornblower’ and doing no work.”15

Churchill’s extensive wartime travels were only beginning. Four months later, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he was again crossing the ocean to meet the President. This time he was travelling on HMS Duke of York. At the end of the voyage, he dictated a letter to his wife to say that he had read Forester’s Brown on Resolution (1929), “which is a charming love story most attractively told.”16 True up to a point. It would have been more accurate, however, to say that the non-Hornblower novel was about the sole able-bodied survivor of a sunken Royal Navy warship in the First World War, who single-handedly delays a German cruiser undergoing repairs long enough to ensure its destruction by pursuers.

After the Second World War, Forester returned to writing about Hornblower. When Churchill received his copy of Lord Hornblower in 1951, he wrote Forester a fan letter:

I read Lord Hornblower during twenty-four hours. I have only one complaint to make about it; it is too short. This is the fault which, if I may say so, belongs in my opinion to all your writings on this inspiring topic. You have created a personality which calls back from the past a grand but hard manifestation of the Royal Navy, in its age of glory. The dark side is not concealed, but, after all we fought and conquered not only for Britain against Napoleon, but kept our place among nations to render other services to the whole world in a succeeding century.

“Thank you so much,” Churchill ended, “for sending me a signed copy which I shall always prize. Please write more about it all.”17

Not surprisingly, a Forester book turned up as part of Churchill’s convalescent reading in summer 1953. “I have been reading Forester’s book about 1814,” Churchill told Lord Moran,” He has the art of narrative; it is only the harmonious arrangement of facts.”18 What worked once, worked again. Nine years later, Churchill suffered a broken hip during a visit to Monte Carlo. He was flown to London and admitted to the Middlesex Hospital. When Prime Minister Harold Macmillan went to visit the patient he described as the Greatest Living Englishman, he noted in his diary that Churchill, then eighty-seven, “was sitting up, reading a novel of C. S. Forester.” “He seemed very cheerful and quite talkative,” Macmillan observed.19

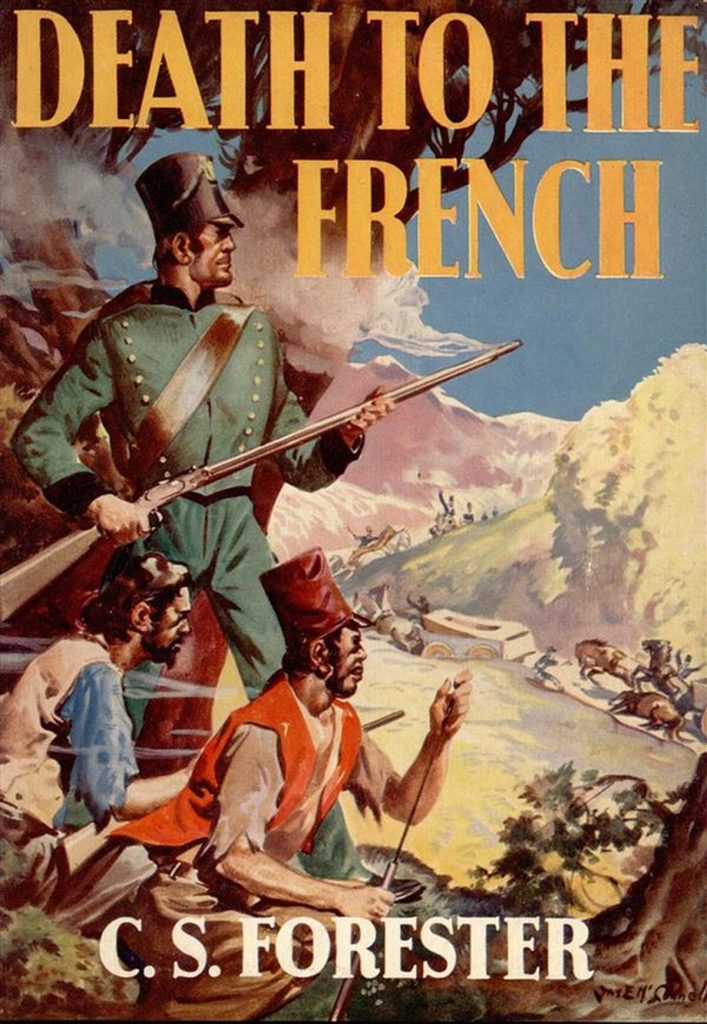

But the greatest story of them all about Churchill’s affinity for Forester comes from the time when he was still Prime Minister in December 1953. Recovered from his stroke, he flew to Bermuda to meet US President Dwight D. Eisenhower and French Prime Minister Joseph Laniel. Twenty years earlier, Forester had written a pair of novels set in the Peninsular War. Churchill chose the flight to Bermuda as the time to read one of them.

The British party was travelling “in high state in the stratocruiser Canopus.” Joining Churchill were Lord Moran, Professor Frederick Lindemann, and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden. For lunch, the four men squeezed into a small table: “the Prof. and the P.M. on one side,” Moran recorded, “Anthony and I opposite.” “After greeting Anthony cheerfully, Winston took up his book…by C. S. Forester, and kept his nose in it throughout the meal.”20 The title of the book: Death to the French.

Endnotes

1. Winston S. Churchill, Thoughts and Adventures (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2009), pp. 317–18.

2. Roy Howells, Simply Churchill (London: Robert Hale, 1965),

p. 109.

3. Ibid. The first film version of Agatha Christie’s play, which she developed from one of her short stories, starred Charles Laughton and premiered in Britain on 30 January 1958.

4. Ibid., pp. 109–10.

5. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Volume VIII, Never Despair, 1945–1965 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1988), p. 145.

6. Ibid., p. 1243.

7. Lord Moran, Churchill (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966), p. 426.

8. Ibid., p. 457.

9. Ibid., p. 465.

10. Ibid., p. 455.

11. Ibid., p. 750.

12. Lady Williams, in conversation with the author, 1 September 2020.

13. Ibid.

14. Edmund Murray, Churchill’s Bodyguard (London: Star, 1988), pp. 93–94.

15. John Martin, Downing Street: The War Years (London: Bloomsbury, 1991), p. 57.

16. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Volume VII, Road to

Victory: 1941–1945 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986), p. 20.

17. Gilbert, Churchill VIII, p. 620.

18. Moran, p. 478.

19. Gilbert, Churchill VIII, p. 1337.

20. Moran, p. 533.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.