Finest Hour 185

The Artist and the Aviator: The Case for Churchill and Roosevelt Viewing Victory Through Air Power

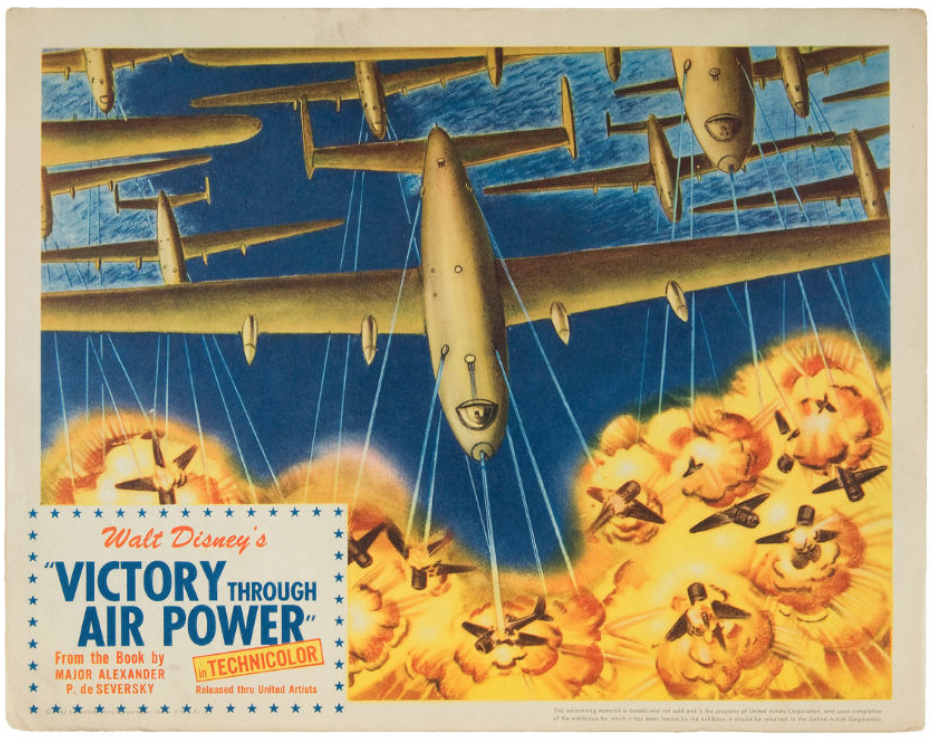

Publicity poster for Victory Through Air Power

August 19, 2019

Finest Hour 185, Third Quarter 2019

Page 34

By Paul F. Anderson

Paul F. Anderson is founder of the Disney History Institute, which focuses on Walt Disney’s creative legacy, and has worked and consulted for the Disney family and company on numerous historical projects.

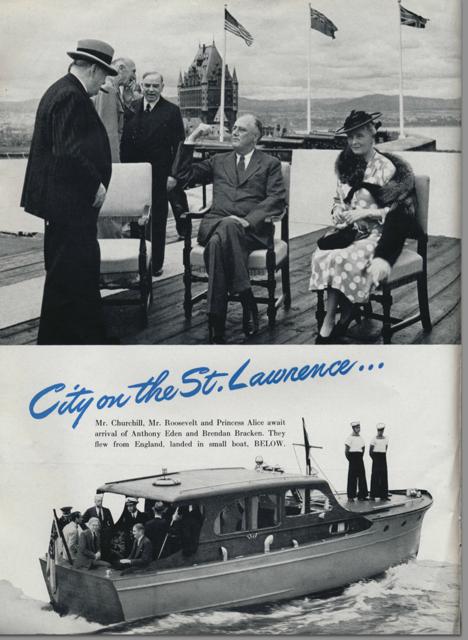

Following the Second World War, the claim was made by Walt Disney and Alexander P. de Seversky that the film Victory Through Air Power (1943), based on the book of the same name, was viewed by Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt at the Quebec Conference. This viewing, the claim continues, helped to increase the support the two leaders gave to strategic air power in defeating the Axis. The story has been repeated by Disney historians ever since. But is it true?

In April 1942 the book Victory Through Air Power by Major Alexander P. de Seversky was published with little fanfare, but within a month it appeared on the New York Times bestseller list. By August it had reached number one—so popular it prompted a paperback reissue, practically unheard of at the time. Interest continued at a fever pitch, and it was condensed for publication in Reader’s Digest and serialized in newspapers. By fall, Gallup’s Audience Research Institute estimated five million people had read the book in one form or another.

The book’s popularity was in large part due to timing. It was the early stages of the war for the United States, and the country had faced many setbacks. The book offered bold solutions, a self-help manual for a frustrated public on how to win the war. The “secret” was long-range air power.

One American totally won over by Seversky’s argument was Walt Disney. In 1941 Walt had caught the flying fever on a goodwill trip to South America, done at the behest of the US Government. “I had decided to make a picture on the history of aviation,” recalled Walt in 1942, and “when I read…Victory Through Air Power, I was impressed with Major Seversky’s clear vision of the present and future role of air power.”1

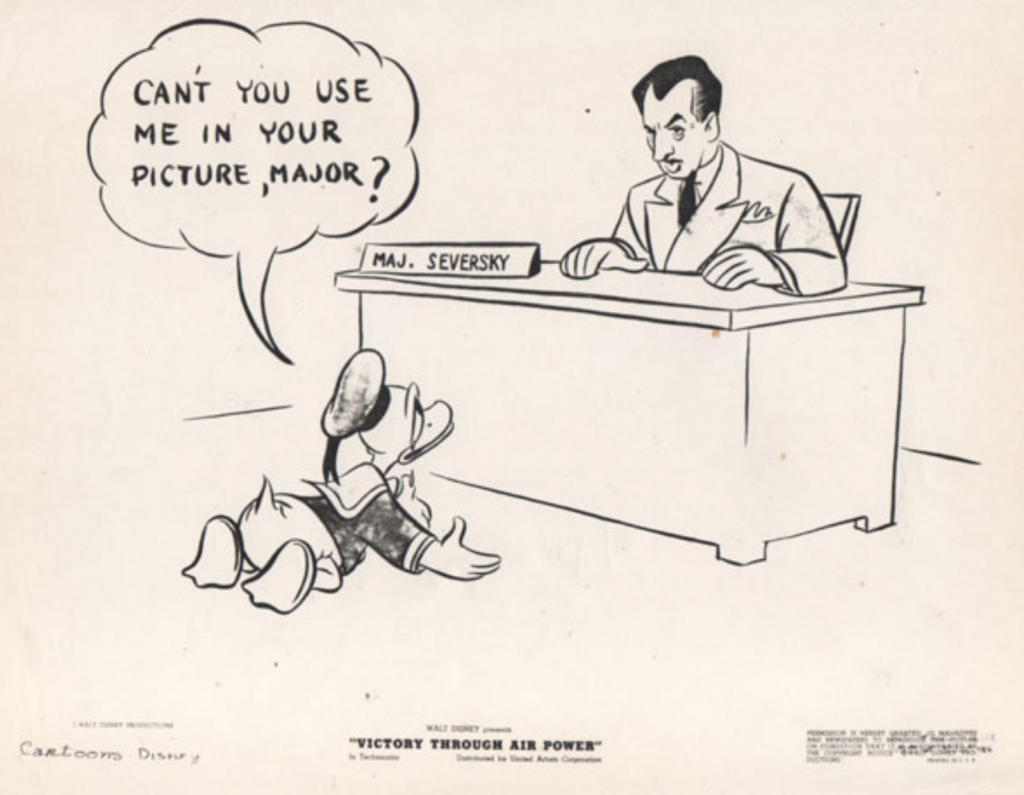

Within a month Walt instructed that the film rights be purchased with the caveat that all inquiries eliminate the Disney name. Straightaway the rights were secured, and Walt contacted Seversky to serve as a consultant. At first the major was puzzled when his secretary informed him that Walt Disney was on the phone; the aviator could not figure out why Mickey Mouse was interested in air power. After a short explanation, Seversky learned that Walt was a student of aviation and was enthralled by the book’s theories. There followed a thirteen-month collaboration during which the artist and the aviator dedicated themselves to making a film about what they unreservedly believed was the strategy for winning the war.

The Claim

A decade after the war ended, a story began to surface that at one of the most desperate times for the Allied powers during the war, the film version of Victory Through Air Power had influenced some very important people during the 1943 Quebec Conference and helped to shape the outcome of the war. The people were Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt. But the evidence supporting this claim is anecdotal and comes primarily from Seversky and Disney sources. It would not be the first time the Disney publicity machine got hold of a tidbit and cultivated it to such a point that myth moved into the realm of accepted truth.

As a historian of the Disney Studio, I have long taken an interest in this compelling story. Churchill and Roosevelt deciding strategy after viewing a Disney film?! I just had to get to the bottom of that. Given the importance of the subject, the existence of so many Disney sources making the claim, and the voluminous documentation that exists for both Churchill and Roosevelt, I thought the task of confirming it all would be easy. Yet after many years of intensive research, I have not found a shred of evidence supporting any screening of Victory Through Air Power at the 1943 Quebec Conference. What follows is my personal journey as a Disney historian to discover the truth, share what I have unearthed, and express my own feelings on the subject.

The Search Begins

Verifying the claim clearly requires a primary source, preferably one created close to the event. Official documents would be best, but the only official document that could conclusively verify that the film was made available to the two leaders would be a military order requesting that it be flown to the Quebec Conference. The Signal Corps was the branch of the US Army that was responsible for all military communications, so somewhere in their records would be an order to have the film flown to Canada. The US National Archives records group where this document would reside, however, has no easy way of finding such an order out of the 1,044,784 items I would have to go through. This was so limiting that I decided anecdotal evidence by the particulars, such as a piece of correspondence or a diary notation, would work as well. Thus I started my quest.

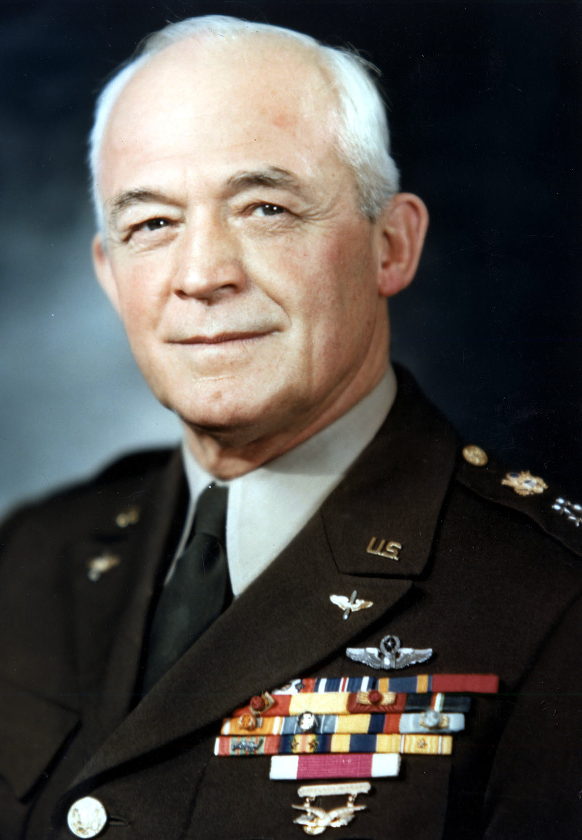

I began seeking any personal anecdotes (written or spoken) from a non-Disney/non-Seversky source. Yet after years of poring through the written records, journals, notes, correspondence, and transcripts of such people as Churchill, Roosevelt, General “Hap” Arnold, General George C. Marshall, Admiral William D. Leahy, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, and others, I found nothing.

The deeper I delved, the more it seemed that some conspiracy was afoot to keep me from finding the truth. Materials concerning the proceedings in Quebec are sparse and inadequate due to the secrecy involved. I was actually informed by a few Canadian historians that, partly because of secrecy and partly because government officials in Quebec did not understand the historic importance of the conference, very few records were kept.

In the Roosevelt Presidential Library, “The Log of the President’s Visit to Canada: 16 August 1943 to 26 August 1943” was prepared by his Naval Aides, which may be the reason there is no mention of a film about Air power. The US Navy was quite afraid of the Disney film, feeling that it might sway public sentiment heavily towards air power and thus away from the navy.

Things did not pan out across the Atlantic either. The staff at the British National Archives at Kew were helpful but could not do the research for me. A professor friend of mine spent a few days digging around Kew on my behalf but once again, nothing. At my request, the Director of the Churchill Archives, Allen Packwood, kindly ran a keyword search of his vast database using “Disney,” “Seversky,” and “Victory Through Air Power,” but answers came there none.

Diaries were kept by Generals Marshall and Arnold. But Marshall was an Army man and not an advocate of air power at the conference, so it was no great surprise to find no mention of the film by him. Arnold, however, commanded the US Army Air Force. Surely he of all people would have something to say. Unfortunately, he was recuperating from heart troubles at the time, and his diary entries concerning the conference are not extensive. Other Quebec attendees did not keep records, and I was unable to locate any useful correspondence.

Seversky Surprise

The Nassau County Libraries in Long Island, New York made me hopeful when I learned that they held the bulk of Seversky’s papers. I had finally found my Holy Grail and would once and for all know that FDR and Churchill had indeed watched the film and that it changed the strategic course of the war towards long-range airpower!

I made my own long-range air plans so I could fly off to my Holy Grail of research. It was not to be. In 1974, Seversky died without heirs, and his papers were given to the Republic Aircraft Corporation on Long Island. A decade later the company was extinct, and the papers made their journey to the Nassau County Library System. Within this loosely-connected federation of Long Island libraries, the papers were passed from location to location until finally, one day, they disappeared!!

I spent weeks on the phone with many helpful folks from the library, and no one knew where Seversky’s papers were or where they might have ended up. The closest I came to discovering their whereabouts and what may have happened was when the Assistant Director told me, “We had a reference collection once, but it was phased out a number of years ago as it was too specialized for us.” I briefly thought about digging around in a few Long Island landfills but ultimately decided against it.

My new Long Island friends continued to look for material, and I was hopeful when they informed me that they had additional research on Seversky done in the early 1990s by an aerospace historian. It appeared that within these personal papers, moreover, that there were documents proving the film’s appearance in Quebec. I went through a portion of these papers, which were held at the Cradle of Aviation Museum in New York, but found nothing. I was told that there were plenty more of Seversky’s papers in the system and that I should not give up. But as of this writing, no more have been found.

More Frustrations

Short of primary source material from the conference principals, I began branching out. General Laurence Kuter was at Quebec as “Hap” Arnold’s assistant chief of air staff for plans and combat operations. An early air power historian, Murray Green, interviewed Seversky on 16 April 1970. In this interview Seversky tells Green the story of the film being shown at the conference and states: “So Larry Kuter was ordered to fly this picture all the way to Quebec. Did he tell you that story?” To which Green replies, “I will ask him about it.”2 The very next day, 17 April 1970, Green did an interview with Kuter…and forgets to ask him about flying the film to Quebec! Kuter died in 1979. History was now taunting me.

I looked for still other individuals who attended the conference, but, along with Kuter, all of the key participants had passed away. So I began searching through the names of staff that might still be alive. I was assisted by two brilliant historians in this process, Dik Daso, curator at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, and Duane Reed, historian at the US Air Force Academy. They thought a member of Arnold’s staff might still be alive. They had not heard of his passing, and such news travels quickly in the tight-knit air-power community. I began my quest to find Jacob Edward Smart.

After more than four months, I managed to track down the retired ninety-five-year-old, four-star general in South Carolina and went to interview him. During the Quebec Conference, he was indeed a key member of Arnold’s staff. But he told me that he was only in attendance at Quebec for the last three days. He missed most of the conference because earlier in the month of August 1943, he was leading the bombing raids over the Ploesti oil fields in Romania. He did recall seeing Seversky on a number of occasions, but Smart could not have seen the film in Quebec since he was not in attendance when it is supposed to have been shown.

The Case for the Defense

Despite the cold trail, there are historical clues that help support the claim made about the showing of the film. The most obvious is that the Allied powers did emerge from the conference with a decided bias towards long-range air power. A telegram from Roosevelt and Churchill was sent to Marshal Stalin of the Soviet Union on 24 August 1943 to bring him up to date on strategic decisions agreed to at the conference. In a statement that would have made Walt and Seversky proud, the telegram read: “The bomber offensive against Germany will be continued on a rapidly increased scale from bases in the United Kingdom and Italy. The objectives of this air attack will be to destroy the German air combat strength, to dislocate the Germany military, industrial, and economic system.”3

While evidence independent of Disney and Seversky is lacking, there is still a good case to be made based on their personal accounts. I studied each one based on what was said, when it was said, how it was said, and then—finally—by considering possible motives. I also took a look at the various deviations from one version to another.

The claim did not appear during the war. This is not surprising since the proceedings at the conference would have been highly classified at the time. Attendees would not have been permitted to speak about it until long afterwards. If Walt did know, he would have been bound by secrecy. The same was true for Seversky. So the fact that the story did not appear until a decade after the war is not surprising. The Ultra Secret, after all, was not revealed until three decades after the war.

The earliest version of the story comes from a 1956 interview Walt did with Pete Martin. In referring to Victory Through Air Power, Walt declares: “It was even flown by special request to Quebec at the Quebec Conference for Churchill and the others to see. And I got that straight from the fellow who flew it up there and he was a General in the Air Corps.”4 (Walt is, of course, speaking of Larry Kuter.) Listening to the interview in context provides even more insight into Walt’s thinking—he is talking casually, commenting on whatever comes into his mind, and it is not rehearsed.

Seversky repeatedly told the story in interviews and articles. The most notable is in a 1967 article he wrote for Aerospace Historian, the official publication of the Air Force Historical Foundation. Seversky wrote that “At the request of Mr. Churchill, General Arnold asked General Larry Kuter, who is now Vice President of Pan American Airways, to have the film flown to Quebec at once. President Roosevelt and Churchill, closeted together, saw the film twice.”5 Not only did General Kuter get this publication, he was on the Board of Trustees for the Air Force Historical Foundation. Never once did Kuter dispute the story, even though he had plenty of opportunity to do so. Seversky had everything to lose and nothing to gain if the story were proved false. Yet during his entire career, he never once wavered from the story—nor was he, or the story, ever challenged.

Seversky and Disney were not the only individuals to tell of the film’s glorious victory in Quebec. The story surfaces in the 1960 book Taken at the Flood: The Story of Albert D. Lasker by John Gunther. Lasker was an advertising executive so taken with the theories espoused in the book that he assisted Disney and Seversky in publicizing the film. This reference at least might be considered an independent source void of any Disney touch. Gunther writes:

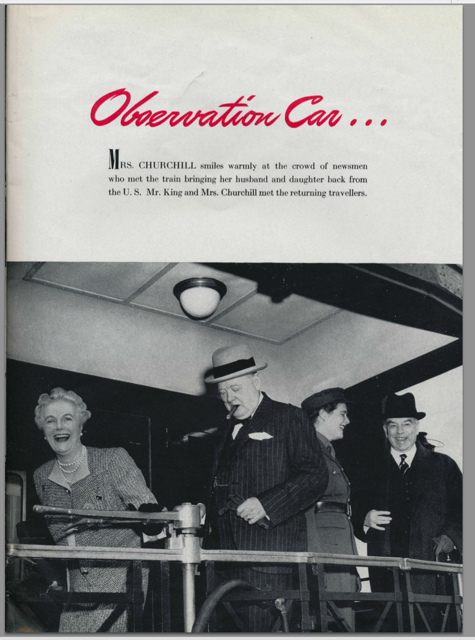

Several times Lasker tried to arrange a meeting between Roosevelt and Seversky, or at the least have Victory Through Air Power shown at the White House; he failed, largely because Admiral Leahy, who thought that Seversky was a crackpot, was now F.D.R.’s watchdog on such matters. Meantime, the film received wide attention in theaters in England. Lasker, through a British friend, got a print to Winston Churchill, and the Prime Minister was much impressed by it.

Came the Quebec Conference between Roosevelt and Churchill in the summer of 1943, critical military decisions, preparatory to the invasion of Europe the next year had to be made, but the conference was deadlocked. F.D.R. and General Marshall wanted to set a definite date for the operation, but Churchill, the RAF, and General Arnold felt that this should not be done until certain conditions were met, such as undisputed command of the air over the English Channel. In an effort to break through this impasse Churchill asked Roosevelt if he had ever seen Victory Through Air Power. F.D.R. said No, and a print was flown by fighter plane from New York to Quebec; the President and Prime Minister saw it together that night privately, and Roosevelt was much excited by the way Disney’s aircraft masterfully wiped ships off the seas. It was run again the next day, and then F.D.R. invited the Joint Chiefs to have a look at it. This played an important role in the decision, which was then taken, to give the D-Day invasion sufficient air power.

A good many years later Lasker heard about the details of all this, and naturally he was pleased and impressed.6

Gunther was a respected journalist and would have had no reason to fabricate the story. My search for the truth took me to Jon Meacham, author of the bestselling Franklin and Winston: An Intimate Portrait of an Epic Friendship (2003) and a member of the International Churchill Society’s Board of Advisers. In our correspondence, he explained that he trusted Gunther’s account: “Gunther was a journalistic insider—one of the great foreign correspondents of his time—who could get in to see the Roosevelts and clearly had excellent sources in the Roosevelt circle.” I asked if Meacham had uncovered anything in his research to support the claim that Roosevelt and Churchill viewed Victory in Quebec. “That story is news to me,” he replied, “but it seems in character: FDR and Churchill often watched movies together, and often recommended films to each other.”7

After Walt

Interviews with Disney old-timers are replete with versions of how Walt saved the day when Victory was shown at the conference. Walt was proud of the film and was not shy about telling the story to those involved. Director H. C. Potter told film historian Leonard Maltin: “Walt told me this story, and swore this was what happened. When Churchill came over to the Quebec Conference, they were trying to get Roosevelt interested in this long-range bombing idea, and Roosevelt didn’t know what the Hell they were talking about. Churchill said, ‘Well, of course you’ve seen Victory Through Air Power…’ and Roosevelt said, ‘No, what’s that?’ Air Marshal Tedder and Churchill worked on Roosevelt until Roosevelt put out an order to the Air Corps to fly a print of Victory Through Air Power up to Quebec. Churchill ran it for him, and that was the beginning of the U.S. Air Corps Long Range Bombing.”8

Even “after Walt” the story has life. It has surfaced in numerous Disney books and articles but always without citation, each retelling built on previously published versions. No one ever questioned the source.

Even “after Walt” the story has life. It has surfaced in numerous Disney books and articles but always without citation, each retelling built on previously published versions. No one ever questioned the source.

Now that I am at the end of my journey, after all the research I have done and countless hours of contemplation, I honestly feel that this should be considered “accepted Disney historical truth.” As a professor and historian, however, I must conclude there is no documented evidence that Churchill and Roosevelt viewed Victory Through Air Power during their 1943 meeting in Quebec. As with many legends, it may not have been the way it was, but it’s the way it should have been.

Endnotes

1. Walt Disney and Alexander P. de Seversky, “A Joint Statement about the Motion Picture ‘Victory Through Air Power,’” New York Herald Tribune, 29 July 1943.

2. Murray Green, “Interview with Alexander P. de Seversky,” 16 April 1970, p. 24.

3. Churchill and Roosevelt to Stalin, 23 August 1943, in William C. Fray and Lisa A. Spar, eds., The Avalon Project: The Quebec Conference, Yale Law School: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy, New Haven, CT.

4.Walt Disney in conversation with Pete Martin, “Walt Disney Oral History, Reel 9,” 1956, Disney History Institute.

5. Alexander de Seversky, “Walt Disney: An Airman in His Heart,” Aerospace Historian, spring, 1967, p. 5.

6. John Gunther, Taken at the Flood: The Story of Albert D. Lasker (New York: Harper, 1960), pp. 285–86.

7. Jon Meacham to author, 19 April 2004.

8. Leonard Maltin, The Disney Films (New York: Hyperion, 1995), p. 61.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.