Finest Hour 185

Churchill, Hitler, and the Battle of Britain

The Supermarine Spitfire

December 22, 2019

Finest Hour 185, Third Quarter 2019

Page 19

By A. P. N. Lambert

Air Commodore Andrew Lambert is a retired RAF officer who flew Phantoms and Tornado fighters. He commanded operations in Northern Iraq, the Falklands, and Bosnia.

In July 1934, just a year after Adolf Hitler’s assumption of power, Winston Churchill declared that Germany had created a rudimentary air force, contrary to the Treaty of Versailles. Hitler already possessed some 400 military aircraft, with an aircraft industry capable of producing 100 more each month. Churchill argued that the German air force was already approximately two-thirds the strength of the RAF’s Home Defence Force.

Churchill also emphasised England’s extreme geographical vulnerability to air attack. While Berlin was some 600 miles away, London was just 100 miles from potential enemy bases. As he said in the House, in words that would come to haunt him in 1940: “With our enormous Metropolis here, the greatest target in the world,…a valuable fat cow tied up to attract the beasts of prey…we are in a position…in which no other country in the world is at the present time.”1

The Chancellor, Sir John Simon, had myopically asserted that a strong economy was “the fourth arm of defence,” leaving Britain unprepared for war in 1938. While the Munich accord did at least give Britain breathing space for rearmament, Chamberlain’s message of “peace in our time” was seen as a message of weakness, not strength.

2024 International Churchill Conference

Amongst the most successful pre-war rearmament measures, however, was the “shadow factory” scheme. Several leading motor manufacturers provided redundant capacity for aeroengine/airframe production with the ability to switch production on demand. By April 1940, Britain was already producing more fighters per month than Germany.

The Dowding System

Almost alone amongst senior RAF staff, Air Marshal Sir Hugh “Stuffy” Dowding, one of the war’s largely unsung heroes, disagreed with Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and the widely held belief that “the bomber will always get through.” This thinking led to the conclusion that the only sure means of defence was being able to threaten more of the enemy’s women and children than they could of yours, and that fighters were therefore of marginal utility. Churchill was one of the few political figures supporting Dowding.

Quietly, and under Dowding’s close direction, Britain had been developing an integrated air defence system that was superior to anything in the rest of the world. Certainly, Germany had point-defence radar, but nothing that brought it all together; indeed, the Luftwaffe considered that radar would give only enough warning for fighters to scramble just before an attack, thereby anchoring them to the point defence of their airfield.

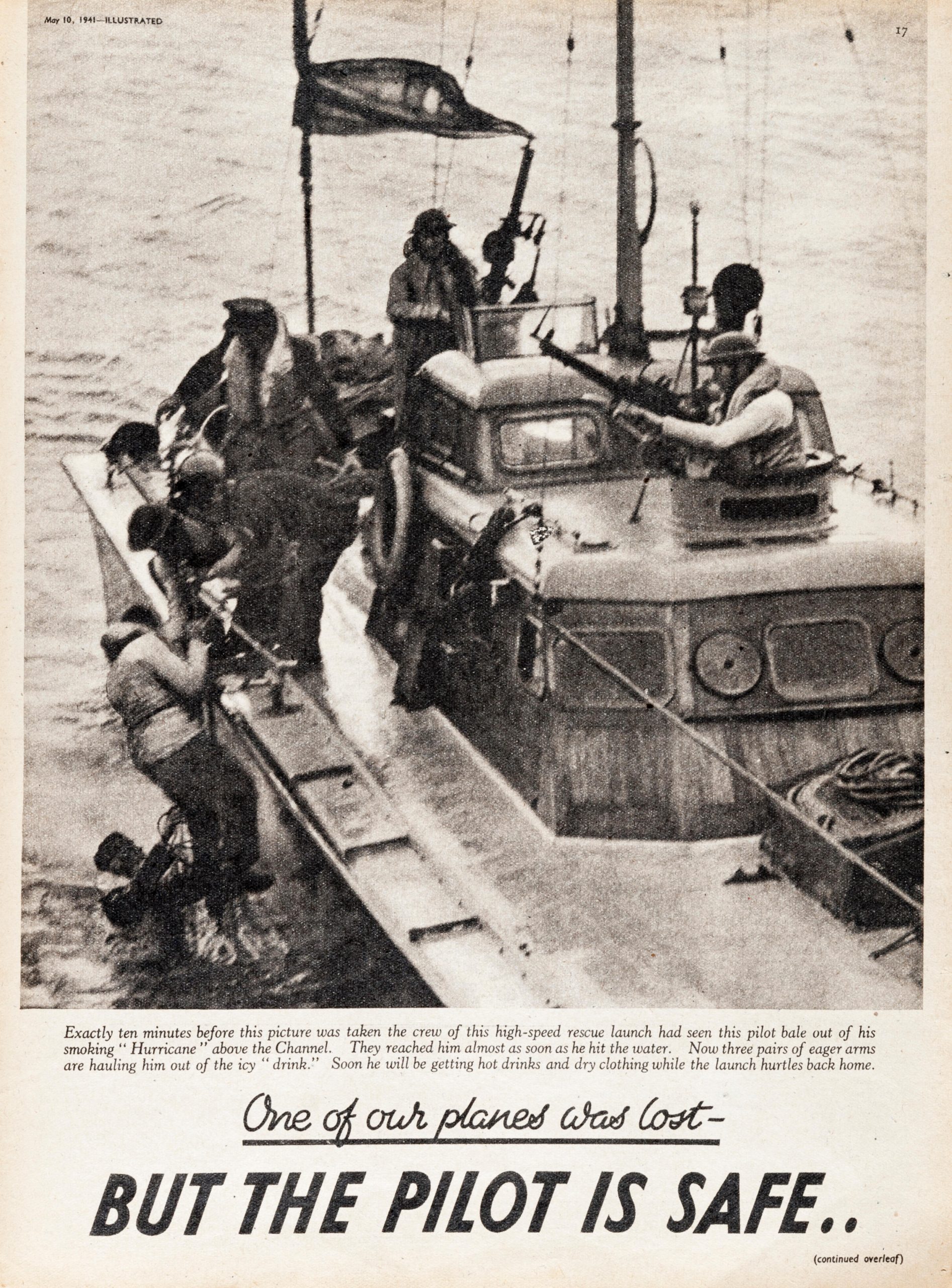

Comprising a series of (unsophisticated) high and low-level coastal radars, with Observer Corps reporting posts overland, radars and observers fed information on air movements to a Filter Room where reports were judged, coordinated, and deconflicted, before being presented to commanders as a minute-by-minute air situation. This, combined with the introduction of modern monoplane fighters, such as the Hurricane and then the Spitfire, allowed Britain to have an effective air shield, which neither the Poles, the French, nor even the Germans, had. As Churchill said: “All the ascendancy of the Hurricanes and Spitfires would have been fruitless but for this system…and all was now fused together into a most elaborate instrument of war, the like of which existed nowherein the world.”2

Not only did this “Dowding System” offer the Commander-in-Chief a recognised air picture, it was disseminated down to operational commanders at Group Headquarters, and still further to Sectors from where fighters could be offered tactical direction by radio (“Vector one-five-zero; climb to Angels two-zero; bandits are in your right two o’clock”). This offered the freedom to intercept wherever seemed best without being tied to geographical features. Moreover, the warning allowed fighters to be held at ground alert and scrambled only to meet incoming raids, thereby avoiding continuous (wasteful) patrols, which required at least three fighters for every one that met the enemy.

Husbanding Resources

Once fighting began, however, Dowding still had to argue against Churchill’s commitment to France. The C-in-C watched almost helplessly as his fighter squadrons were steadily committed into a losing battle, leaving his air defences progressively denuded. On 16 May, a message from French General Gamelin asked for ten more fighter squadrons “at once.” Churchill flew to Paris. In acrimonious discussions, the defeat of France was being attributed to Churchill’s failure to provide sufficient air support. The Prime Minister gave way.

Dowding was alarmed: “our armies may well be defeated in France but, assuming we are to fight on, the minimum air defence necessary was assessed as 52 squadrons yet we have only 36 remaining, of which in the last few days a further 10 have been also despatched.” He demanded:

as a matter of paramount urgency the Air Ministry will consider and decide what level of strength is to be left to the Fighter Command for the defences of this country, and will assure me that when this level has been reached, not one fighter will be sent across the Channel however urgent and insistent the appeals for help may be…if the Home Defence Force is drained away…defeat in France will involve the final, complete and irremediable defeat of this country.3

Roughly two-thirds of all fighters sent to France were lost, with many just abandoned in various states of repair. Equally worrying were losses in groundcrew and support equipment. Fortunately, with airbases far from the Panzer assault, many were later repatriated from uncaptured French ports, though the RAF lost some 800 men when the troopship Lancastria was bombed and sunk on 17 June.

Fateful Decisions

Following the fall of France, Churchill warned ominously:

What General Weygand called the Battle of France is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin….Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this Island or lose the war.…Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves, that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, “This was their finest hour.”4

Immediately, Churchill appointed the press baron Lord Beaverbrook as Minister of Aircraft Production. Beaverbrook overhauled all aspects of war-time aircraft production. He increased production targets by 15% across the board, took control of aircraft repairs and RAF storage units, and was perpetually at odds with all other departments, especially in his prioritisation of aircraft over tanks.5

Had there been no English Channel, the Wehrmacht would no doubt have marched successfully on London. Hitler’s ill-considered invasion of Norway, however, had virtually destroyed his Kriegsmarine. Just three capital ships remained available, and no assault on Britain could be contemplated against a British Home Fleet of nine battleships, three carriers, nineteen cruisers and up to a hundred destroyers dominating the home seas, and with the Royal Air Force still commanding British skies.

Hitler favoured an invasion only if there was no other way. German naval commander Admiral Raeder understandably favoured a joint air-naval blockade, seeing invasion prospects as very uncertain. The best timing for such an attack, in Raeder’s judgement, would not be until May 1941. But Hitler was not convinced that such a delay was acceptable. The weather could be as bad in May, the Royal Navy no less strong, and the British Army far more prepared. All this argued that the balance would swing in Britain’s favour.

Illustrated magazine, summer 1940

And here the fatal overconfidence of Luftwaffe commander Herman Göring combined with Hitler’s opportunism. Göring, a highly successful fighter pilot who had been awarded the Blue Max in the First World War, had supported Hitler in his rise to political power, and was now minister for rearmament, a post for which his natural arrogance, morphine addiction, and laziness made him particularly unsuited. His Luftwaffe had indeed done well, but only as a striking arm of the new Blitzkrieg form of attack, and any independent role was outside the Luftwaffe’s doctrine, capability, and practice. Of course, given the weakness of the Kriegsmarine and the vulnerability of any invasion armada, success in the air offered the best prospect of protecting any rapid dash across the Channel. To prevent RAF attacks on the invasion fleet, as well as to offer some defence against the Royal Navy, the Luftwaffe had first to gain mastery of the skies.

Hitler signed Directive 16 for Operation Sea Lion (the invasion of Britain) on 16 July. For this, air superiority was a sine qua non.

Hoping to appear statesmanlike, Hitler spoke in the Reichstag on 19 July in a low-key style offering Britain his victor’s terms. After what seemed a very reasonable offer by the “Master of Europe,” Germans were incredulous when the proposal was almost flippantly rejected— though with some justification it turns out once the terms for defeated France became known.

If Britain could still be coerced or defeated: well and good. If not, then she would be finally isolated once Russia were conquered. But, if the invasion were to be postponed to 1941, as Raeder wanted, any assault would inevitably conflict with Operation Barbarossa (the invasion of Russia). So, would it be Barbarossa in 1941, followed by Britain in 1942? Or would Churchill simply capitulate once Moscow fell? Perhaps Hitler wanted to keep all his options open. If air superiority, then Sea Lion; if not, then Barbarossa! Probably Hitler thought his indecisiveness was flexibility.

Göring, far more preoccupied with his own business, failed to attend any of Hitler’s meetings. On 30 July, therefore, Hitler sent a brusque note directing Göring to put his forces at twelve hours’ notice to “begin the great battle of the Luftwaffe against England.” On 31 July, however, at a meeting with his senior generals in Berchtesgaden, Hitler directed that planning should already begin for the assault on Russia.

Objectives

The aims of Göring’s “great battle” were for the Luftwaffe to grasp air superiority, destroy the rest of the RAF, prepare the ground for invasion (while protecting its own bases and ports), and perhaps even coerce the British into surrender. If invasion were ordered, the Luftwaffe would defeat the Royal Navy’s task forces, protect the invasion fleet, and provide support for the offensive on London—quite a tall order!

For the RAF, in contrast, the task was simple: survive.

The German concept of battle was founded both on military momentum and ill-considered strategic clichés. There was little real prospect of success, but much to be lost through failure.

Bizarrely, the Battle of Britain did not need to be fought at all. Hitler could have consolidated his position on the continent, ignored the British, and begun his planning for Barbarossa. The British could have retreated to their island home, licked their wounds, built up their depleted forces, and considered what to do next. But the die was cast.

Führer Directive 17 (“The Conduct of Air and Naval Warfare against Britain”) was issued on 1 August. Its purpose was to “establish conditions favourable for the conquest of Britain.” The attack would begin on 5 August, with “the priority to overcome the British Air Force…in the shortest possible time,” then to concentrate on bombing enemy ports, except those required for Sea Lion. Terror attacks on cities were withheld.

The Luftflotte commanders, with bases dotted along the Channel coast, saw it as their primary task to destroy the RAF’s fighters, not only by attacking British airfields, but also by air combat in the skies over Britain. Göring believed that this was achievable in just four good days, with the campaign begun by Adlerangriff, an “eagle attack.”

Unsurprisingly, Luftwaffe direction of the battle was erratic. When the weather was good, the offensive was not ready; once begun, targets seemed chosen at random, and priorities reflected changing strategies. RAF forward operating bases were heavily struck while main fighter bases were almost ignored; when Adlerangriff was finally ordered on 13 August, it was then cancelled due to weather. The first real coordinated attack finally began on 15 August.

While RAF fighters concentrated on bombers, they became vulnerable to fighter escorts. According to wildly optimistic Luftwaffe Intelligence, by 16 August eight RAF bases were deemed to be out of action and 770 RAF fighters destroyed. Nevertheless, the Luftwaffe’s vulnerable Stukas had had to be withdrawn from combat, and fighter escorts tied ever closer to the bombers.

Pivoting

Churchill followed the battles closely, and many Cabinet discussions focused on pilot training and fighter production. On 16 August, the Prime Minister visited HQ 11 Group and, witnessing the bravery and losses as aircraft plummeted, said he “had never been so moved,” “never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few,” words that he used later in his famous Commons speech.

Both sides sought to characterise it as a great and glorious battle. But in reality, it was a campaign of attrition. In air combat two factors are dominant: the unseen fighter, and shortage of fuel. In both cases, the British had an advantage. With radar, RAF fighters were warned of the location of the enemy, and in dogfights over Britain German fighters were always at a fuel disadvantage. Added to this were the capture of downed German pilots, the relative ratios of fighter production, the incompetence and bluster of Göring, and the ambivalence of Hitler. Though a hard-fought battle, the result was probably inevitable.

Although attacks on cities were withheld, navigation errors, and just plain fear, caused an increasing number of bombs to fall on civilians. In July, 258 had been killed followed by 1,075 deaths in August. On the night of 18– 19 August, bombs fell on southwest London. Extensive bombing of central London followed on the 22nd and 23rd, and further bombing of Slough and the West on the 23rd and 24th.

As the weight of German bombs on London increased, Churchill pressed the War Cabinet to endorse reprisal attacks on Berlin. Whether this was a deliberate inducement to divert German effort from the hard-pressed RAF airfields onto the vast city of London remains a subject of debate. Perhaps London was indeed “a valuable fat cow tied up to attract the beasts of prey”—a necessary sacrifice to alleviate the suffering of Fighter Command.

The RAF first raided Berlin on the night of 25 August 1940. Hitler, in a blast of offended righteousness, condemned the RAF bombers as pirates, and, in his Sportpalast speech of 4 September, asserted that Germany’s response would be to repay the British tenfold, and determined now to “eradicate” British cities. The transfer to attacking London had two effects. First, it did indeed reduce pressure on British fighter airbases, but—equally—the greater distance to London for German bombers reduced their fighter escort time. This, and the additional time the RAF was given to assemble “Big Wings,” made German bombers increasingly vulnerable. As Luftwaffe losses mounted, daylight bombing became unsustainable.

Aerial Trafalgar

On 15 September, Churchill visited HQ 11 Group and witnessed what is now regarded as the peak of the battle. Churchill asked Air Officer Commanding Air Vice Marshal Park what reserves he had; the answer was “none.” But that week the Luftwaffe lost 298 aircraft, including ninety-nine fighters, while the RAF lost 120.

Fighter Command was far from beaten. When 17 September came, the compiler of the War Diary at German War Headquarters recorded: “The enemy air force is still by no means defeated; on the contrary it shows increasing activity. The weather situation as a whole does not permit us to expect a period of calm….The Führer therefore decides to postpone ‘Sealion’ indefinitely.”6

For Hitler, it may not have been his “main show,” but its impact was indeed strategic: Britain would fight on despite the nightly bombing attacks of the Blitz; the US public would progressively support Britain; and the mighty German war machine was now clearly beatable. Opportunism had proved no substitute for proper strategy.

In a 1942 broadcast, George Orwell suggested that the Battle of Britain had played the same part in history as Trafalgar in 1805. In both cases victory minimised the risk of invasion, even though it still took many years to win the war, but in the autumn of 1940 that was sufficient.7

Endnotes

1. Commons Debate, 30 July 1934, Hansard, vol. 292, cc. 2325–447.

2. https://books.google.com/books?id=800EAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA47

3. Letter C-in-C Fighter Command to the Air Council, 16 May 1940, in Norman L. R. Franks, RAF Fighter Command (London: Patrick Stephens, 1992), p. 62.

4. Churchill, Speech to House of Commons, 18 June 1940.

5. Geoffrey Best, Churchill and War (London: Bloomsbury, 2005), p. 178.

6. German Naval Staff Records in John Killen, The Luftwaffe: A History (London: Pen and Sword, 2013), p. 149.

7. Richard Overy, The Battle of Britain (London: Penguin, 2004), p. 122.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.