Finest Hour 185

Action This Day – Summer 1894, 1919, 1944

4.1.2

November 20, 2019

Finest Hour 185, Third Quarter 2019

Page 42

By Michael McMenamin

125 Years Ago

Summer 1894 • Age 19

“Bring Molly”

In My Early Life, Churchill wrote a misleadingly benign account of his fatally-ill father’s departure on a round-the-world tour. He received by messenger, Winston wrote, “the college adjutant’s order to proceed at once to London. My father was setting out the next day on a journey round the world….We drove to the station the next morning—my mother, my younger brother, and I. In spite of the great beard, which he had grown during his South African journey four years before, his face looked terribly haggard and worn with mental pain. He patted me on the knee in a gesture which however simple was perfectly informing. There followed his long journey round the world. I never saw him again, except as a swiftly-fading shadow.”

The disagreement between Winston and his father as to whether he would go into the Infantry, as his father insisted, or the Cavalry, as Winston wanted, was never resolved before his father’s death in January 1895. They exchanged letters on the subject during Lord Randolph’s global journey, but to no result. Winston optimistically wrote his mother on 10 July that he hoped to “pass high” his Sandhurst exams “…as I shall take the opportunity of writing a long letter to Papa on the subject of Cavalry. I have been piling up material for some time and I have a most formidable lot of arguments.”

In the event, Winston did write such a letter, but it did not impress his father, who replied: “I do not enter into your lengthy letter…in which you enlarge on your preference for the Cavalry over the 60th Rifles. I could never sanction such a change….So that you had better put that out of your head altogether at any rate during my lifetime during which you will be dependent on me. So much for that subject.”

Fortunately for Winston, there was more to life that summer than his father’s morose behavior. He and his brother Jack went to Switzerland on holiday that August, but earlier, during July, he enjoyed the company of Adela Mary (nicknamed both Polly and Molly) Hacket, with whom he enjoyed a friendship and correspondence from late 1893 through most of 1894. He wrote to his mother in on 30 December 1893 that he was sorry to be leaving Blenheim “and nothing but the thought of the beautiful Polly Hackett consoles me.” Miss Hacket, also nineteen, had similar feelings for him. She wrote to Winston on 28 March 1894 apologizing for not having answered his earlier letter and offering as an excuse: “I have been waiting for your photograph which you promised and I want so much.” On 18 July, his brother Jack wrote him from Harrow saying, “Mind and come on Saturday & Bring Molly. I will have Tea in my room à la Xmas 92. You remember. But let me know whether she is going to come.”

2025 International Churchill Conference

Apparently, Molly did come with him, and without a chaperone, for Winston bragged about it to his mother in a 22 July letter: “Yesterday Molly Hacket and I made our great expedition to Harrow—quite alone. As soon as we got down there—we received three telegrams with ‘Congratulations’ from young Clay and others,” Clay being Herbert Spender-Clay, a Churchill friend and fellow Sandhurst cadet. Both Molly and Winston knew they were being “naughty” by Victorian standards in travelling “quite alone” and by having “tea” in a boy’s room. The fact they received congratulatory telegrams meant they had told their friends ahead of time about their “great expedition.”

100 Years Ago

Summer 1919 • Age 44

“A Fatal Mistake”

The Civil War in Russia continued during the summer to be a source of irritation between Prime Minister Lloyd George and Churchill, the Minister for War and Air. The War Cabinet determined on 4 July that “a state of war did exist as between Great Britain and the Bolshevist Government of Russia.” Some 200 ships of the Royal Navy were thus blockading Russia’s Baltic ports.

The Prime Minister had the responsibility to fashion a consensus through his War Cabinet on a policy for Britain’s self-acknowledged war with the Bolsheviks. But other than to persuade the War Cabinet to withdraw British troops in Northern Russia—a decision made before Churchill entered the Cabinet as Secretary for War but which he successfully implemented—Lloyd George never did this. As a consequence, the Cabinet lurched from crisis to crisis during the summer of 1919 when it came to making decisions about offering aid in the form of munitions, food, and trade to the anti-Bolshevik armies operating in Northern and Southern Russia.

Churchill outlined his position on “Britain’s Foreign Policy” in the 22 June edition of The Weekly Dispatch. In it, he urged four specific points: (1) that Britain remain “firm friends” with the United States; (2) that it “in concert with the United States…aid and protect France who has been so terribly weakened by… the war”; (3) that Germany “after an interval which should not be too long, should take her place in the League of Nations” because “we cannot afford to drive the German Nation into the jaws of Russian Bolshevism.”

His fourth point was that “Russia, too, will be wanted in the League of Nations as one of the great agents and guarantors of the peace and progress of the world. But Bolshevik Russia can never form part of such a League. The Bolshevik leaders themselves would be the first to admit this.…They seek as the first condition of their being the overthrow and destruction of…every…Government now standing in the world.”

Churchill summarized this last point: “To sustain and encourage all those forces in Russia which are striving for the destruction of the Bolshevik tyranny and the establishment of the Russian people upon a broad and genuine democratic basis.”

Notwithstanding the War Cabinet’s recognition that “a state of war” existed between Britain and the Bolsheviks, nothing remotely resembling Churchill’s proposed foreign policy on Russia was ever adopted. On the evening of 29 July, after the Cabinet failed to adopt his policy, Churchill spoke in the House of Commons and neatly summarized the policy toward Russia that, by default, became British foreign policy: “We should make a fatal mistake if we assume…that we should not interest ourselves in the affairs of Russia, and that we should leave the Russian people to stew in their own juice.” Sadly, what Churchill feared came to pass.

75 Y ears Ago

Summer 1944 • Age 69

“Get anything out of the Air Force you can….”

Following the success of the D-Day landings, new developments in the war kept Churchill fully occupied in the summer of 1944. On 13 June, the Germans began firing V-1 rockets at Britain. By 6 July, these terror weapons had killed 2,752 civilians, more than the 2,443 British troops killed during the Normandy landings. When Home Secretary Herbert Morrison suggested that some Allied forces in France be diverted from their drive toward Germany and sent to capture V-1 launching sites on the French coast, Churchill said no. The Prime Minister explained somewhat callously to the House of Commons that: “This form of attack is, no doubt, of a trying character, a worrisome character… but people have just got to get used to that.”

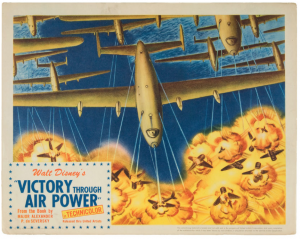

Early in July, the British government learned that more than two-and-half million Jews had been murdered in gas chambers at Auschwitz, previously thought to be only a slave-labor camp. Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann appealed to Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden to bomb the railways from Budapest leading to the camp. Eden passed this on to Churchill who told Eden, “Get anything out of the Air Force you can, and invoke me if necessary.” Eden went to the Secretary State for Air, who told him it was “out of our power,” as it could be done only during daylight raids, which the RAF could not do. Only the Americans flew daylight bombing, and the US War Department had turned down such a request on 26 June. US policy subsequently remained unchanged.

Churchill sailed for Quebec on 5 September to attend another conference with President Roosevelt. He was accompanied by his wife Clementine and arrived in Nova Scotia on 10 September, where they took a train to Quebec City and were greeted at the station by President Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor. During the meetings, FDR floated the scheme conceived by Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau to convert “Germany into a country primarily agricultural and pastoral in its character,” with no industrialization permitted. Churchill and FDR signed an agreement to this effect. In a telegram to the War Cabinet, Churchill said that he “was at first taken aback” by the proposal but then began to think of “the beneficial consequences to us” that might follow. The plan quickly died, however, for various reasons. Among them, Churchill changed his mind when Field Marshal Brooke “pointed out that a populous Germany would be needed as a future ally against Russia.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.