Finest Hour 177

Churchill, the Royal Navy, and the Bismarck

The Bismarck

October 5, 2017

Finest Hour 177, Summer 2017

Page 40

By Fred Glueckstein

In his war memoirs, Winston Churchill wrote of the danger in the Atlantic: “Besides the constant struggle with the U-boats, surface raiders had already cost us over three-quarters of a million tons of shipping. The two enemy battle-cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the cruiser Hipper remained poised at Brest under the protection of their powerful A. A. batteries, and no one could tell when they would again molest our trade routes. By the middle of May [1941] there were signs that the new Battleship Bismarck, possibly accompanied by the new 8-inch-gun cruiser Prinz Eugen, would soon be thrown into the fight.”1

Based on naval intelligence, Churchill knew the German battleship was a fast and powerful vessel and the most heavily armored ship afloat. The Bismarck had eight 15-inch guns in four turrets, two fore and two aft. It also had eighty-one smaller guns, mostly anti-aircraft.

The Bismarck also had a special anti-torpedo belt made of nickel-chrome steel, which the Germans believed would ensure that no torpedo in use by the British could penetrate. With some reason, Germans were convinced that the Bismarck was nearly unsinkable.

Design, Construction, and Launching

In 1934, the German Navy’s Construction Office began work on the preliminary and contract design on the Battleships designated “F” (Bismarck) and “G” (Tirpitz). Dr. Hermann Burkhardt designed the ships. On 16 November 1935, five months after Germany signed the Anglo-German Naval Treaty, the Bismarck was officially ordered. The contract for building the ship went to the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg.

On 1 July 1936, the keel was placed and construction began. On 13 February 1939, Adolf Hitler was at the Blohm & Voss shipyard to preside over the launching of the ship. More than 60,000 people, including government and military officials as well as yard workers, were in attendance.

In his pre-launch speech, Hitler formally named the vessel in honor of Germany’s statesman Otto von Bismarck. Dorothee von Lowenfeld-Bismarck, daughter of von Bismarck’s second son, smashed a champagne bottle on the bow and declared: “On the order of the Führer, I christen you with the name Bismarck.”2

The new ship’s captain was Ernst Lindemann. The crew of the Bismarck numbered 103 officers, including the ship’s surgeons and midshipmen and 1,962 petty officers and sailors. Fleet staff, prize crews, and war correspondents raised the number on the Bismarck to more than 2,000.3

On 8 August 1940, Churchill wrote to Archibald Sinclair, the Secretary of State for Air, and Cyril Newall, the Chief of Air Staff, to examine the possibility of “heavy attacks” on the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau at Kiel, the Bismarck at Hamburg, and the Tirpitz at Wihelmshaven, as they were all targets of supreme importance.4On 13 October, Churchill wrote to General Ismay for the Combined Chiefs of Staff: “The greatest prize open to Bomber Command is the disabling of Bismarck and Tirpitz.”5 Churchill’s desire did not occur.

Towards the end of April 1941, the Bismarck was provisioned for three months at sea. Captain Lindemann entered in the War Diary: “Even though my crew, with few exceptions, has had no combat experience, I have the comforting feeling that, with this ship, I will be able to accomplish any mission assigned to me. This feeling is strengthened by the fact that, in combination with the level of training, we have for the first time in years a ship whose fighting qualities are at least a match for any enemy.”6

On 1 May, Hitler inspected the Bismarck and Tirpitz. Although quiet during the inspection and briefings, Hitler was aware of the British Fleet’s superiority and concerned that the big ships might be lost, which would also hurt his prestige. Hitler also thought that commerce raiding deviated from the proper mission of warships; however, he reluctantly permitted the operation.

Fearful that Hitler might change his mind, Erich Raeder, Commander in Chief of Kriegsmarine, and Günther Lütjens, Fleet Commander, did not inform him that the Bismarck was scheduled to sail in two weeks. The ship’s departure was not reported until the Bismarck had been at sea for four days.7

Heading to the Atlantic

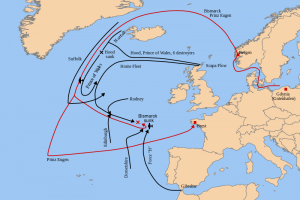

The Royal Navy’s pursuit of the Bismarck began on 21 May 1941 at 0800 when the Admiralty received a coded message from a British agent in Sweden. The previous afternoon, the agent had seen two large German warships steaming north through the strait between Sweden and Denmark.

The ominous report was transmitted to Sir John Tovey, the commander in chief of the Home Fleet aboard his flagship King George V.8 Aerial reconnaissance identified the German warships as the battleship Bismarck and the Prinz Eugen. It was clear to Admiral Tovey that the Bismarck was headed to the North Atlantic to sink British shipping.

Tovey was correct. The Operation Order for the Bismarck issued by Raeder and the Chief of the Seekriegsleitung, Admiral Schniewind, on 2 April 1941 read: “The primary mission of this operation also is the destruction of the enemy’s shipping; enemy warships will be engaged only when primary mission makes it necessary and it can be done without excessive risk.”9

The Bismarck’s presence was extremely troubling to Tovey, as ten prized convoys were at sea. An eleventh convoy with 20,000 troops for Egypt was ready to sail the next day, with the aircraft carrier Victorious and battle cruiser Repulse as escorts. Tovey was aware that none of the convoys had necessary naval defenses against the Bismarck.

Tovey knew the Bismarck had to be found and destroyed. His Home Fleet at Scapa Flow included two new 35,000-ton battleships, his flagship King George V and her sister ship Prince of Wales. The 42,000-ton Hood, also a battle cruiser, was available. It was the largest vessel in the Navy and its pride. Like all battle cruisers, however, the Hood had forgone armor protection for speed. Upon deliberation, Tovey knew that the only ship that could challenge the Bismarck was the Hood.

Sinking of the Hood

On the night of 21 May, a squadron of the Home Fleet, including the Hood and the Prince of Wales, sailed from Scapa Flow to confront the German ships. The Admiralty also ordered Vice Admiral James Somerville northward from Gibraltar with Force H—Renown, Ark Royal, the cruiser Sheffield, and six destroyers—to protect the convoy that was out to sea with 20,000 troops or to join in the battle. Somerville’s ships left Gibraltar on the 24th, and as Churchill later wrote: “They carried with them, as it turned out, the Bismarck’s fate.”10

At 0535 on 24 May, British lookouts saw on the horizon the shapes of two German warships. Soon, the Hood and Prince of Wales confronted the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. After both sides opened fire, the Hood and Prince of Wales were ordered to turn to port away from the Germans to allow them to use their aft guns, and to fire broadsides with all their large cannon.

American journalist William L. Shirer wrote of what occurred: “As the British ships veered around, a salvo from the Bismarck hit the Hood midships. Observers on both sides saw a scene they had never before looked upon at sea. Between the two funnels of the Hood there was suddenly a volcanic flame that erupted skyward for a thousand feet. Then in a second or two it burned out, and a dense cloud of smoke settled over the sea.”11 Of the 1,419 men aboard the Hood, only three men were picked up alive. Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland, Captain Ralph Kerr, and the rest of the crew went down with the ship.

Upon learning of the Hood Churchill wrote: “At about seven I was awakened to hear formidable news. The Hood, our largest and also our fastest capital ship, had blown up. Although somewhat lightly constructed, she carried eight 15-inch guns, and was one of our most cherished naval possessions. Her loss was a bitter grief, but knowing of all the ships that were converging towards the Bismarck I felt sure we should get her before long, unless she turned north and went home.”12

Inside six hours of the loss of the Hood, the Admiralty deployed a number of warships against the Bismarck, which included four battleships, two battle cruisers, two aircraft carriers, three heavy cruisers, ten light cruisers, and twenty-one destroyers.

Chasing the Bismarck

The Royal Navy was unaware the Bismarck had been damaged. One of the two shells from the Prince of Wales had pierced the German vessel below the water line and exploded among some of her oil tanks, blowing a hole in the ship’s side. Water poured into the damaged tanks, making the remaining fuel unusable and causing the ship to leave an oil slick in its wake.

With its fuel supply fast dwindling, the Bismarck reduced speed. In addition, the ship’s rudder was jammed, which affected its steering. The mighty German battleship was in dire straits. After confirming that the Bismarck was trailing oil, the Prinz Eugen broke away permanently to refuel from a tanker and undertake action on its own.

In the early morning of 25 May, the British lost contact with the Bismarck. Unknown to them, Fleet Admiral Guenther Luetjens onboard the Bismarck decided that the ship would steam southeast to St. Nazaire for repairs. Due to an error in plotting, Tovey believed the German warship would be heading to its home port through the Norwegian Sea, and he sailed northerly with the Home Fleet, searching in vain for his prey.

Meanwhile, Vice Admiral Somerville raced full speed northwest with Force H. At the same time, Captain Dalrymple-Hamilton of the battleship Rodney under the command of Tovey believed that the Bismarck was heading toward France. He decided not to follow orders and remain where he was. Somerville, who was not under Tovey’s direct command, also disregarded orders for the northeast search.

On the afternoon of 25 May, Tovey was radioed the position of the Bismarck. He was shocked to learn that the German battleship was heading southeast to a French port and not sailing north for her home haven. The Admiral’s navigation officer checked his plotting and confirmed the arithmetic mistake. At 1810, Tovey directed the Home Fleet to a new course southeast.

While the Admiralty ordered all British ships in the Atlantic to try and intercept the Bismarck, its exact location was unknown. Efforts to find the German warship by three Catalinas, American flying boats, were unsuccessful.

Air Marshal Sir Frederick Bowhill, a rare blend of an English officer who had been both in the merchant marine and a pilot in the RAF, had a feeling the Bismarck was headed for Brest or St. Nazaire. The Admiralty agreed and extended the search further north. The entire search area became a “rectangle tilted northeast” about two hundred miles long and a hundred miles wide.

On 26 May, scouting planes from Somerville’s Ark Royal were sent out at dawn. By ten o’clock there was no news from the scouting planes. At 1030, however, a message was received by a dozen British ships from a Catalina: “…One battleship…sighted…position 49 30 north…21 50 west…steering 150 degress [roughly southeast by east]…speed…20 knots….”13 The Bismarck was again located.

By 26 May, the British fleet was upon the Bismarck. Among the ships were the Ark Royal, Renown, Sheffield, and the destroyer flotilla of Captain Philip Vian.

After receiving the Admiralty’s radio signal that a Catalina had found the Bismarck, Captain Benjamin Martin of the heavy cruiser Dorsetshire, escorting a northbound convoy 300 miles north of the Bismarck, felt he had a good chance of intercepting the warship. Captain Martin decided to intercede.

On a second aerial attempt, fifteen Swordfish biplanes from the Ark Royal, each carrying one 1,600 pound torpedo under its fuselage, attacked the Bismarck; two, possibly three struck the warship. Captain Vian’s destroyers were then surrounding the Bismarck.

The Reckoning

On the 27th, Churchill went to the Admiralty and watched the scene on the charts in the War Room. News was received every few minutes. While the Royal Navy was engaging the Bismarck, Churchill left the Admiralty and went to the House of Commons to report about the battle in Crete and the Bismarck.

“This morning shortly after daylight the Bismarck, virtually at a standstill, far from help, was attacked by the British pursuing battleships,” said Churchill. “I do not know what were the results of the bombardment. It appears, however that the Bismarck was not sunk by gunfire, and she will now be dispatched by torpedo. It is thought that this is now proceeding, and it is also thought that there cannot be any lengthy delay in disposing of this vessel. Great as is our loss in the Hood, the Bismarck must be regarded as the most powerful, as she is the newest, battleship in the world.”

Churchill had just sat down when a slip of paper was handed to him, and he rose again. Asking for the indulgence of the House, he said: “‘I have received news that the Bismarck is sunk.’ They seemed content,” wrote Churchill.14

Churchill later wrote about what occurred: “It was the cruiser Dorsetshire that delivered the final blow with torpedoes, and at 1040 the great ship turned over and foundered. With her perished nearly 2,000 Germans and their Fleet Commander, Admiral Lutjens. One hundred and ten survivors, exhausted but sullen, were rescued by us. The work of mercy was interrupted by the appearance of a U-boat and the British ships were compelled to withdraw.”15

For Churchill and the English people, the sinking of the Bismarck was an important triumph against Hitler. At the time, it had an important effect on the nation’s morale. Most importantly, it safeguarded future shipping convoys on the Atlantic, which were vital to the nation’s survival. The Royal Navy’s success in sinking the Bismarck entered the annals of England’s esteemed naval history.

Fred Glueckstein is a regular contributor to Finest Hour and author of Churchill and Colonist II (2014).

Endnotes

1. Winston Churchill, The Second World War, vol. III, The Grand Alliance (London: Cassell, 1950), p. 270.

2. John Asmussen, Bismarck & Tirpitz: The History. http://www. bismarck-class.dk/index.html

3. Baron Burkard Von Müllenheim-Rechberg, translated by Jack Sweetman, Battleship Bismarck: A Survivor’s Story (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1980), pp. 29–30.

4. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. VI, Finest Hour 1939–1941 (Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press, 2011), p. 711.

5. Winston Churchill, The Second World War, vol. II, Their Finest Hour (London: Cassell, 1949), pp. 444, 578.

6. Von Müllenheim-Rechberg, pp. 62–63.

7. Ibid., p. 72.

8. William L. Shirer, The Sinking of the Bismarck (New York: Random House, 1962), p. 6.

9. Von Müllenheim-Rechberg, p. 256.

10. Churchill, The Grand Alliance, p. 272.

11. Shirer, p. 35.

12. Churchill, The Grand Alliance, p. 272.

13. Shirer, p. 82.

14. Churchill, The Grand Alliance, p. 283.

15. Ibid.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.