Finest Hour 182

War Lord in Training: Churchill and the Royal Navy during the First World War

December 19, 2018

Finest Hour 182, Fall 2018

Page 20

By Matthew S. Seligmann

Matthew S. Seligmann is Professor of Naval History at Brunel University, London, and author of Rum, Sodomy, Prayers, and the Lash Revisited: Winston Churchill and Social Reform in the Royal Navy 1900–1915. See review on p. 44.

Churchill’s contribution to naval affairs in the First World War is a polarizing topic. It divided people at the time and it remains a matter of sharply delineated opinions even now. The reasons for this are not difficult to spot. Although no decisive sea engagement was fought while Churchill was First Lord of the Admiralty, the opening ten months of the war were nevertheless eventful, and the operations that took place at that time appeared to highlight the worst aspects of Churchill’s character as a civilian naval leader. The reality is—inevitably—more complex, but a quick check of what went visibly wrong and what appeared to go right will illustrate the point.

The First World War began at a fortuitous moment for the Royal Navy: a test mobilization had been carried out in July 1914, and the main fleet of dreadnought battleships and battle cruisers was therefore already assembled and crewed when the moment of destiny arrived. All that was required was to withhold the order to disperse and despatch the ships instead to their designated war stations. That was all well and good, but what would happen thereafter was less clear.

There is a famous story recorded in the brutally frank diary of Captain Herbert Richmond, then Assistant Director of Naval Operations, that on the second day of the conflict Churchill had remarked that “Now we have our war, the next thing is to decide how we are going to carry it on.”1 For the intellectual and hyper-critical Richmond, Churchill’s off-the-cuff admission was simply appalling. It was, he confided, “a damning confession of inadequate preparation for war.”2 Richmond’s outrage would have been fully justified had the First Lord’s quip been illustrative of the state of the Royal Navy in 1914. It was not, however, strictly speaking, true; or, at least, it was not entirely true, and Churchill had played an important role in many important reforms instituted prior to the outbreak of hostilities.

Home Waters

I n the period from October 1911, when Churchill was appointed to the Admiralty, to August 1914, when war broke out, a great deal of time and effort had been expended on readying the Royal Navy for a trial of strength against Germany. A naval staff had been created, new ships had been designed and ordered, more powerful weapons had been introduced, steps had been taken to create a naval aviation service, a start had been made to transform the coal-powered fleet into one that would be fuelled in the future by oil, pay and conditions for both officers and men had been improved in the quest to ensure that the service could both recruit and retain the number and quality of personnel that it needed, and plans of various kinds had been drawn up for what to do should the cataclysm come. Churchill had played a characteristically significant role in these reforms, and many of his contributions were positive. For example, the Admiralty had been charged with making sure that should the government decide to send an army to France, it would get there safely. Come the day, the Navy was prepared to protect the transports carrying the Expeditionary Force across the Channel. All of them arrived without mishap.

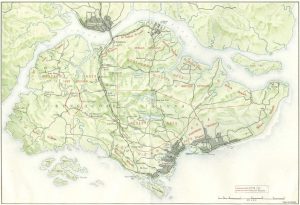

There were, however, other areas where things did not run smoothly. In the years before 1914, for example, the British naval leadership had wrestled with the question of how to conduct a campaign against Germany. In some respects this was straightforward. The British Isles were a natural 600-mile breakwater blocking Germany’s access to the open ocean. German warships could be hemmed into the North Sea, German merchant vessels denied access to the high seas, and neutral trade with Germany could be significantly curtailed. The fundamental ingredients for a campaign of economic warfare were thus in place.

Geography, although an aid in some respects, was a hindrance in others. In particular, Britain’s 600- mile east coast was difficult to defend. Warships scattered along its length to protect all parts could easily be isolated and defeated in detail. Concentrating the fleet in one location, however, also created challenges, since there were no fortified harbours along the majority of this coastline that could accommodate such an array of warships in safety. This compelled the Admiralty to seek a base out of range of German torpedo boats where the Royal Navy’s big ships would be safe from a surprise attack. Several such anchorages existed in Scotland. There were advantages and disadvantages to each, however, and the Admiralty found it hard to make a decision. The result was that come August 1914 some work had been undertaken at each location, especially Rosyth. Churchill had requested extra funding from a reluctant Treasury to expedite matters, but none of the anchorages was actually complete. Thus, when the fleet sailed for Scapa Flow at the start of August, the ships reached a spacious but largely unsecured position. It did not take long for the lack of defences to become a source of anxiety. As the potential of German submarines became ever more obvious, the fear grew that Scapa Flow could be penetrated by u-boats and British ships sunk while at anchor. To avert this, parts of the fleet were regularly dispatched to the supposedly safer waters west of Scotland. It was there that the brand new super dreadnought HMS Audacious struck a German mine and foundered.

Was this perilous position Churchill’s fault? It is always possible that this disaster would have happened anyway: that even without the fear of u-boats, big ships would have been sent away for gunnery practice and one of them would have struck a mine and been lost. That, however, is a counter-factual. In reality it was fear of u-boats that drove the Grand Fleet to practice shooting in western waters. Arguably, therefore, Audacious was a victim—and an expensive one—of the Admiralty’s inability to decide upon and secure funding for a properly defended base in advance of war.

The second challenge posed by the selection of Scottish harbours was that they were located at the very northernmost tip of Britain. Consequently, ships based there were stationed at a considerable distance from much of the shoreline that they were supposed to protect. Indeed, they were further away from East Anglia and the south Yorkshire coast than was the German fleet in Wilhelmshaven. This raised the possibility that should the Germans undertake an operation against a British port, not only might they reach their target unimpeded, but worse still, having made an attack, they might get clean away before the British force sailing south from Scotland could intercept them. This unwelcome prospect had long been known to British authorities. Manoeuvres in 1912 and 1913, both of which had modelled German raids, had illustrated this clearly, and the danger had been admitted by Churchill at the Committee of Imperial Defence.

Although the so-called “North Sea Problem” had been easily identified, no viable solution had been found by the time the fighting started; and the war would show that it was no mere hypothetical possibility. On 3 November 1914, German battle cruisers shelled the Norfolk coastal town of Great Yarmouth. On 16 December, a raid was undertaken against Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby. Civilians were killed, and the British public railed against the brutal German “baby killers,” as Churchill promptly labelled them—thus alchemizing this vivid demonstration of national vulnerability into a valuable propaganda coup. Nevertheless, the fact that the Royal Navy could not prevent such attacks reflected badly on the service and its leaders, Churchill included.

Overseas

Difficulties also existed in preserving British interests in more distant waters. Much thought had gone into the defence of the wider empire. Nevertheless, many early war-time efforts went badly awry. The first major mishap occurred in the Mediterranean. This was a vital artery of empire, linking the metropolis to territories in India, Australasia, and the Far East. As a result, the Royal Navy had traditionally maintained a strong presence there. Admittedly, in 1912, Churchill had wanted to scale this back in order to concentrate on the North Sea, but after the Germans created their Mittelmeer Division—consisting of the new battle cruiser Goeben and the modern light cruiser Breslau—there was no doubt that a powerful British force was needed to counter this. Accordingly, at the outbreak of war, the British Mediterranean Fleet consisted of two battle cruisers and four armoured cruisers. Their mission was to locate their German counterparts, bring them to battle, and destroy them. They failed.

Sir Archibald Berkeley Milne, the C-in-C Mediterranean, had assumed that the German ships would head west in order to return to Germany and had deployed his battle cruisers accordingly. When the German vessels actually sped east to Constantinople, he was ill-placed to stop them. The armoured cruisers, commanded by Rear-Admiral Ernest Troubridge, were better situated and actually had an opportunity to bring the Germans to battle. Troubridge, however, had previously received orders not to engage a superior force. Believing that his armoured cruisers were outclassed by the German battle cruiser and that his instructions meant that he should not therefore oppose them, he declined to fight. As a result, the German ships were able to reach Constantinople unharmed. Once there, they added impetus to the decision of the Ottoman government to aid Britain’s enemies.

The escape of the Goeben and Breslau was a fiasco that did no credit to the Royal Navy; and Churchill, although not the commander on the spot, cannot escape a share of the blame. Indeed, he was directly implicated. To begin with, he had appointed both Milne and Troubridge—neither of whom could be said to represent the cream of the naval officer corps—to these desirable and, as it turned out, highly important commands. Moreover, especially in the appointment of Milne, Churchill had done so against the explicit advice of the former First Sea Lord, Lord Fisher. In Fisher’s opinion, Milne was more courtier than naval leader and would prove a disaster in any serious test. He berated Churchill for putting relations with the King ahead of his duty to the Navy. Events did not suggest that Fisher was wrong. This was not all. Churchill had played a part in drafting the orders that Milne and Troubridge had received and had also sent out a number of ambiguous signals during the vital early days of the war. This poor staff work, which both Milne and Troubridge would later cite in defence of their actions, again came down partly to Churchill.

If the war began badly in the Mediterranean, it did not prove any more successful in Latin America. At the outset of the conflict, the German East Asia Squadron commanded by Maximilian Graf von Spee had disappeared into the vast wastes of the Pacific Ocean. Where it would reappear was a matter of conjecture, but British forces were deployed to meet it wherever that turned out to be. One of these was the North American Squadron led by Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. Cradock’s armada was something of a hodgepodge. At its heart were two obsolescent armoured cruisers: Good Hope and Monmouth. In addition, Cradock had at his disposal the aging pre-dreadnought battleship Canopus, the armed merchant cruiser Otranto, and, his sole modern warship, the light cruiser Glasgow. Quite how such a ramshackle force was supposed to engage the modern and powerful German East Asia Squadron was not entirely clear, and Cradock’s orders, like those to Milne and Troubridge, were not free of ambiguity.

It appears that Churchill expected Cradock to keep his ships together so that, in the event of an encounter with the Germans, the heavy artillery of the Canopus could keep the Germans at bay. This was hardly a winning strategy. Moreover, given that Canopus could barely make twelve knots (half what Spee’s ships could do), keeping the rest of the squadron under the shelter of its guns effectively ruled out searching for the Germans. If Cradock was going to find his opponent, he would need to leave the Canopus behind. He did so. Unfortunately that meant that when his rag-tag collection of vessels located Graf Spee’s greatly superior force, the result was catastrophe. At the battle of Coronel, both Monmouth and Good Hope were sunk with heavy loss of life. As with the escape of the Goeben and Breslau, Churchill was not there on the spot and cannot take the blame for battlefield decisions over which he had no control. At the same time, however, it was his administration that put together Cradock’s ill-assembled squadron and exposed it to its doom.

Victories?

Of course not every engagement ended in defeat, but even the victories displayed deficiencies that reflected badly on the Churchill Admiralty. One such was the battle of Heligoland Bight in August 1914, when the Royal Navy undertook a raid in strength into German home waters during which three German light cruisers were cut off and sunk. To all intents and purposes this was a clear victory, not the least because it intimidated the Kaiser, who—fearing further losses—placed heavy restrictions on his admirals’ ability to conduct offensive operations. What this masked, however, was the total confusion that surrounded the British attack. Owing to poor staff work and inadequate communication, not all of the British units taking part in the battle were aware that the Admiralty had ordered additional forces to sea that day. As a result, on several occasions British vessels were misidentified by other British vessels as hostile. Only good fortune prevented a series of blue on blue attacks that might well have produced serious losses.

Failings also marred the Battle of Dogger Bank. On 24 January 1915, the battle cruisers of the German First Scouting Group were ambushed by their British counterparts. In the ensuing engagement, the German armoured cruiser Blücher was sunk—a photograph of her final moments providing an excellent propaganda piece for the Royal Navy. Once again, apparent success masked an underlying failure, namely that the remaining German ships escaped; and they did so due to poor British command, control, and communications procedures. To add insult to injury, after-battle analysis, which might have corrected this defect, did not do so. Once again, while one cannot blame Churchill for decisions taken on the spot, deficiencies in organization can be laid at his door.

The Dardanelles

Of course, Churchill’s tenure as First Lord is inescapably tarred by the attempt to force the Dardanelles. As Christopher Bell has shown, Churchill’s political opponents used this campaign, often in unfair ways, as part of their efforts to oust him. The opprobrium he has received for this ill-executed and costly operation is, thus, not fully deserved. Equally, however, for all the eloquence and skill of his defence, it was undoubtedly a failure—one moreover that cost Churchill his job. As with the battles previously described, poor staff work played a major part in this. This is significant, because inadequacies in this area underscored so many of the problems faced by the Royal Navy in the First World War.

But can Churchill be blamed? In one sense, clearly he can. The Admiralty War Staff was an organization he had devised, and its wartime activities were under his supervision. On the other hand, the Naval Staff was a new creation. It had come into being in early 1912, meaning that fewer than two years were available to hone and refine it before war came. Unsurprisingly, the Naval Staff was not ready, but the ways in which it was deficient would not become evident until it was put to the test. Eventually, the problems would be ironed out, and the Naval Staff would be transformed into a proficient planning body. This, however, came too late for Churchill, who neither escaped criticism for the Naval Staff’s early failures nor reaped the benefits of its later successes. Such is politics. Accordingly, it would be in the Second World War rather than the First that Churchill would make his reputation as a successful war leader.

Endnotes

1. A. J. Marder, ed., Portrait of an Admiral: The Life and Papers of Sir Herbert Richmond (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1952), p. 92.

2. Ibid.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.