Finest Hour 177

Winston Churchill and the “New Navalism”

December 26, 2017

Finest Hour 177, Summer 2017

Page 12

By W. Mark Hamilton

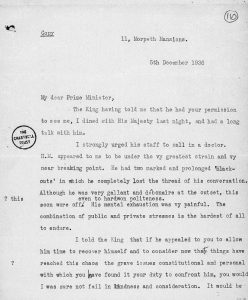

At the start of his parliamentary career in 1901, Winston Churchill promoted the old Victorian themes of “peace, retrenchment, and reform,” but at the conclusion of his first decade as an MP, he was a champion of what was known as “New Navalism” and a vocal advocate of a greatly enlarged Royal Navy. At mid-decade, he had changed his party political affiliation from Conservative to Liberal.

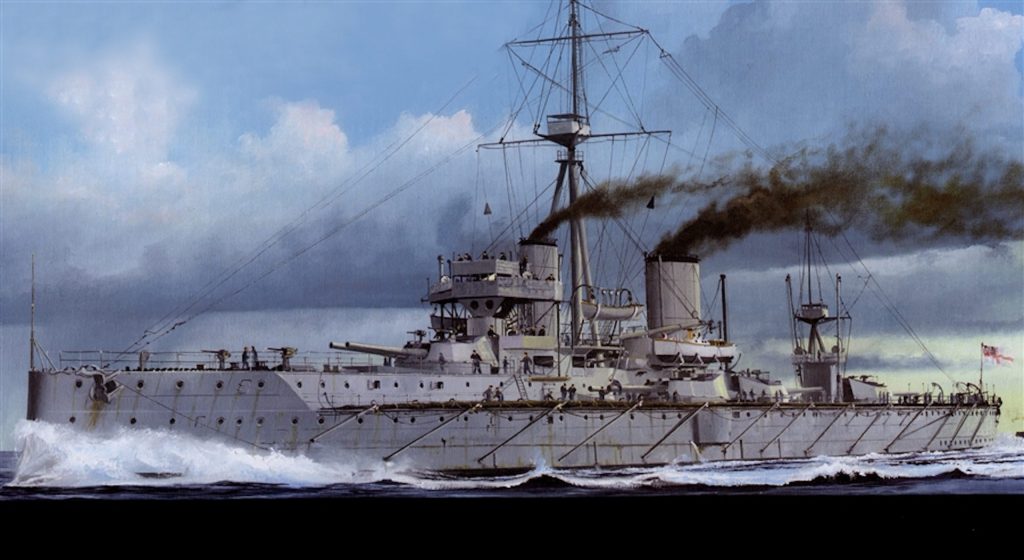

The Royal Navy for centuries had been a central fabric in British life, with a glorious and long history. In the first decade of the twentieth century, however, the Senior Service found itself threatened by rival naval powers, which it had never experienced in a global supremacy lasting a hundred years. In 1914, the British Navy was almost as sacred as the Crown—and just as popular. Public interest in the strength of the Royal Navy heightened as the total amount of naval expenditures surpassed all previous records.

The period of “New Navalism” stretched from 1889 until 1914, during which time there was but one three-year period (1905–1908) when naval expenditures were not increasing. The “New Navalism” was a natural product of the combination of economic nationalism and national imperialism, as promoted by the American “Father of the New Navalism,” Alfred Thayer Mahan.

Little Navalist

With his departure from the Conservative Party to the Liberal Party in 1904, Churchill pushed back against this tide of the “New Navalism.” In addressing the Cobden Centenary meeting in June 1904, Churchill said that he protested the “machinery of national slaughter and hoped…the Liberals could promote a reduction of armaments.”1

2025 International Churchill Conference

As late as 1908, with his close political ally David Lloyd George, Churchill called the Navy “a toy for the rich,” and the War Office he termed the “Ministry of Slaughter.”2

The Navalists would, with Churchill’s arrival as First Lord of the Admiralty in October 1911, speak of his previously held reformist “Little Navy” views, and they would remain chronically suspicious of Churchill’s political agenda.3 In even stronger reformist language, Churchill had said, “I see little glory in an Empire which can rule the waves and is unable to flush its sewers.”4

At the time of the 1907 Second Hague Peace Conference, Churchill had noted, “Europe is now groaning beneath the weight of armies. There is scarcely a single important government whose finances are not embarrassed; there is not a parliament or a people from whom the cry of weariness has not been wrung.…”5

After 1889 there had been a growing sense of British national insecurity, and by 1914 the nation was a great imperial power on the defensive. After 1900, the “New Navalism” took on both importance and urgency, as the British were increasingly insecure in a highly competitive world.

The Naval Lobby

Who were these Navalists with whom Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty had to contend? The British Navy League, established in 1895, was one of the most visible and vocal forces in the organization and dissemination of Navalism. The League was founded to secure popular support for a strengthened British Navy and to make large sections of the public aware of the obligations and duties of British sea power. Press baron Alfred Harmsworth was a charter member of the Navy League, as were Fleet Street journalists, including The Times’ James Richard Thursfield.

The Navy League was a solid middle-class patriotic organization, and one that the great aristocratic families and the Royal Family served as patrons but rarely as active participants. Churchill himself was a member but seemed, as did the other elites, to have avoided active participation and in fact on occasion resented the League’s strong naval agitation and what he saw as interference with “official” naval policy. The League historically had worked to bolster the influence of the professional sea-lords at the expense of the civilian First Lord of the Admiralty. In 1911, Churchill did serve as honorary vice-president for the Port of Manchester branch of the League,6 and in 1922, he could be found speaking at Navy League-sponsored public meetings decrying the decline of British sea power.7 He had avoided another fiercely patriotic group—the Imperial Maritime League, which had been critical of Churchill’s early years as First Lord, but then reversed its views as war approached.8

Even though Churchill’s Liberal Party was less “Navalist” than the Conservatives, the party of H. H. Asquith and Sir Edward Grey contained a strong Navalist lobby. Navalism was never as incompatible with Liberalism as many radicals liked to claim, and the Royal Navy met other needs besides those of national defense and imperial power—e.g., jobs.9

British per capita defense spending before 1914 was the highest of the great European powers, and Navalism was a vital part of Edwardian militarism. Navalism was not just strategic, but was a political and ideological movement to enhance national prestige. In Britain, the most prominent public exponents of Navalism were the popular leagues and political pressure groups.

The British Navy League, the Imperial Maritime League, and the National Service League could justly claim in 1914 more members and adherents than any political party of the period. Public confidence in the Royal Navy sharply increased in the aftermath of the Boer War and the British Army’s less-than-stellar performance.

The Ambivalent Navalist

No British politician had a longer relationship with the Royal Navy in the twentieth century than did Churchill, even though as a youth he had been an “army man.” As late as 1909, Leo Maxse’s National Review attacked ministerial leaders of the “Little Navy Party,” citing David Lloyd George and Churchill.10

In April 1909, The Times published a letter from Churchill, then president of the Board of Trade, arguing against any British naval-building rivalry with the ambitious United States of America.11 At the same moment, Churchill pleaded with the Admiralty for naval contracts to relieve the unemployment in the Clyde and Tyne naval yards.

In 1909, the “Naval question” had severe competition from a variety of pressing domestic political issues including tariff reform, Irish home rule, social welfare, and women’s rights. Social needs even touched the Royal Navy, with Navy League demands for improved lower-deck catering and visits by League leaders to sample food onboard Mediterranean fleet ships. This event could have sparked the campaign of Churchill and Admiral Sir John Fisher for reform of lower-deck conditions. It was also in 1909 that the naval-building “dreadnought panic” commenced, which ultimately never subsided before the outbreak of war in 1914. The Navalist slogan referring to needed new dreadnoughts was, “We want eight and we won’t wait!” Churchill observed, “The Admiralty had demanded six ships; the economists offered four; and we finally compromised on eight.”12

The First Lord of Navalism

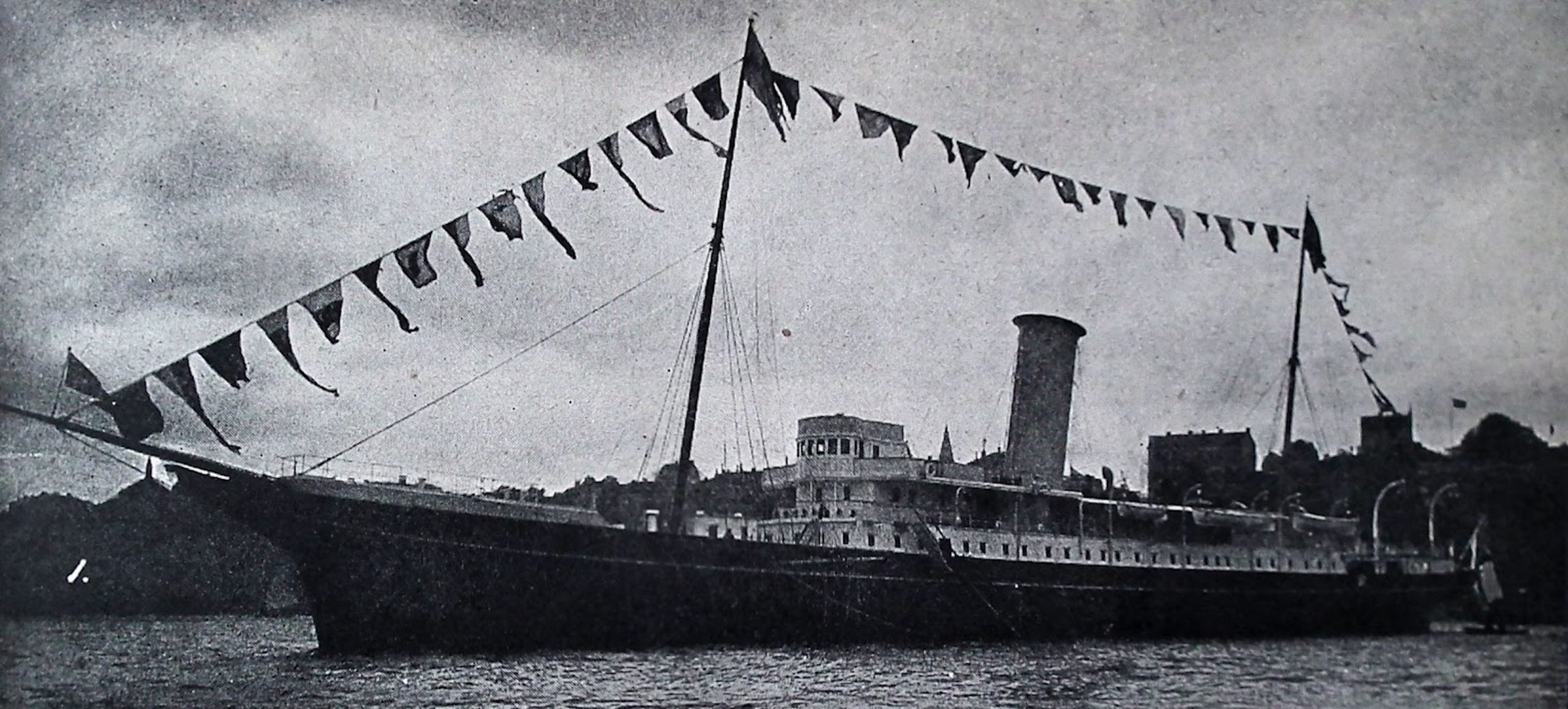

By the time Churchill arrived at the Admiralty in October 1911, his view had changed dramatically, and he had adopted a strongly pro-Navalist agenda. This sharp reversal of attitude did not escape Lloyd George, who wrote to Churchill, “You have become a water creature. You think we all live in the sea, and all your thoughts are devoted to sea life, fishes, and other aquatic creatures. You forget that most of us live on land. ”13 When not in London, the First Lord was aboard the Admiralty yacht Enchantress, inspecting ships, naval dockyards, bases, and schools, always asking questions, questions, and more questions.

The Liberal government and Churchill came under Navy League attack for allowing Trafalgar Square to be used for public speeches and demonstrations. Trafalgar Day as a national commemoration had been suggested and promoted by leading Navalists, but George Bernard Shaw had no use for the “Cult of Nelson” and suggested Nelson’s grand column be torn down!

As always completely engaged in his new responsibilities, Churchill became acutely aware of the Imperial German naval threat. With the Agadir Crisis (July 1911), he firmly concluded that Germany was a serious threat to British naval supremacy and to the wider European balance of power. From this crisis point forward, Churchill’s mind was never free of military matters, and—as the British had been for centuries—particularly sensitive to any naval challenge.14 As Churchill himself stated, he went to the Admiralty to “discharge this responsibility for the four most memorable years of my life.”15

As the years passed and war approached, Churchill became increasingly concerned with the German naval challenge, as the arms race intensified and the shrill voices of Navalism grew louder. But he never became a prisoner of the “New Navalism” even as Armageddon approached. In March 1912, he suggested a “Naval Holiday,” by which he meant the temporary suspension of British and German naval building. He reached out to the Canadian and Australian governments for imperial naval support.

The Gathering Storm

In many respects, Churchill and the ruling elites were the “official minds of Navalism,” but they could never totally escape the public pressures and influences that swirled around them.

The methods and organization of the “New Navalism” and Churchill must be placed within the context of the wider European events, which ultimately led to war in the summer of 1914.

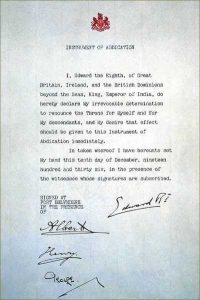

Of all the major historical debates of the last century, none has been more attractive to successive generations of historians than the origins of the First World War. It has been described as the seminal catastrophe of the twentieth century. The “New Navalism” had been a major contributor to this catastrophe, and the escalating Anglo-German naval race must be seen as the major underlying force leading to war between London and Berlin. Winston Churchill and his Royal Navy were ready when the confrontation came.

W. Mark Hamilton holds a Ph.D. in International History from the London School of Economics and Political Science and is author of The Nation and the Navy: Methods and Organization of British Navalist Propaganda, 1889–1914 (1986).

Endnotes

1. W. Mark Hamilton, The Nation and the Navy: Methods and Organization of British Navalist Propaganda, 1889–1914 (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1986), p. 332.

2. William Manchester, The Last Lion: Winston Churchill, 1874–1932 (Boston: Little Brown, 1983), p. 406.

3. H. V. Bonham–Carter, Winston Churchill as I Knew Him (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1965), p. 256.

4. Randolph Churchill, Winston S. Churchill, vol. II, Young Statesman, 1901–1914 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1967), p. 267.

5. Robert Rhodes James, Churchill: A Study in Failure, 1900– 1939 (London: Littlehampton, 1969), p. 26.

6. Matthew Johnson, “The Liberal Party and the Navy League in Britain before the Great War,” Twentieth Century British History, 22:2 (2011), p. 145.

7. Christopher Bell, Churchill and Sea Power (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 101.

8. N. C. Fleming “The Imperial Maritime League: British Navalism Conflict, and the Radical Right, 1907–1920,” War in History, 23:3 (1916), p. 319.

9. Johnson, p. 137.

10. Ibid., p. 147.

11. Ibid., p. 149.

12. Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis, vol. I, 1911–1914 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1923), p. 33.

13. Randolph Churchill, p. 558.

14. Roy Jenkins, Churchill: A Biography (London: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 202.

15. Manchester, p. 431.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.