Bulletin #190 — Mar 2024

Yankee Connections

To view in full, right click and choose "Open in New Window"

February 26, 2024

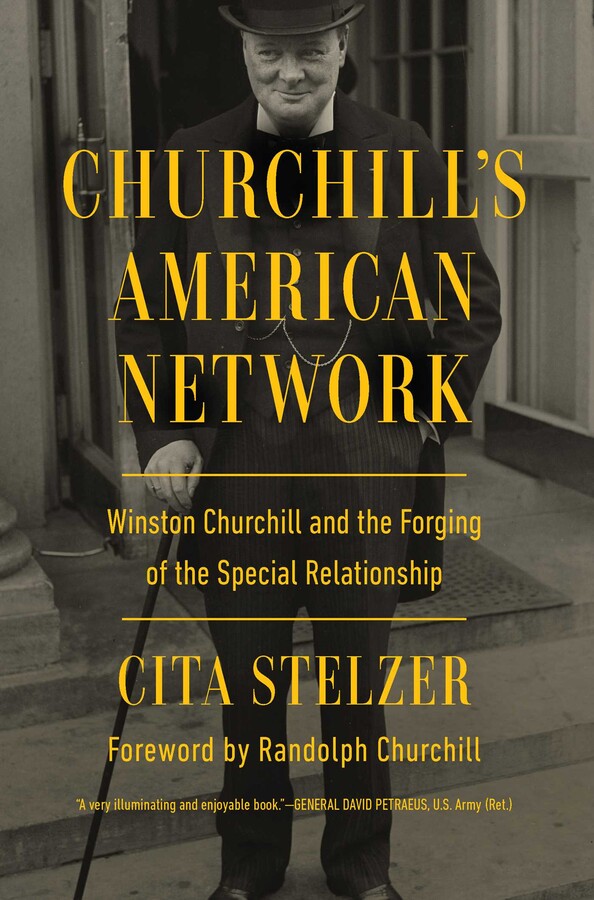

Cita Stelzer, Churchill’s American Network: Winston Churchill and the Forging of the Special Relationship, Pegasus, 2024, 336 pages, $29.95. ISBN 978–1639364855

Review by Oliver Rhodes

The Senate Committee on Foreign Relations had much to discuss in 1941, including the question of Winston Churchill’s credibility as a war leader. Chairman Tom Connally, an isolationist, asked the hearing whether the Prime Minister could be trusted on his promise not to handover the Royal Navy to Hitler in the event of invasion. “Senator, I have known Winston Churchill for twenty-five years,” protested Robert McCormick of Chicago. “A more thoroughly honourable man never lived.”

McCormick was an isolationist, a Republican and no friend of the British Empire. Thankfully, however, McCormick was part of Churchill’s American network—the subject of a new study by Cita Stelzer.

Churchill is not the only British Prime Minister to have courted America, but he was, far and away, the most successful.Churchill’s American Network: Winston Churchill and the Forging of the Special Relationship documents Churchill’s visits to the United States in 1895, 1901, 1929 and 1931-32. It shows how Churchill’s cultivation of friendships across the Atlantic swayed American public opinion in his country’s favour at the moment of crisis.

2024 International Churchill Conference

The American network was long in the making. In 1901, at twenty-six, Churchill was already carving his profile as a speaker and war hero on the western side of the Atlantic. The Chicago Tribune, then edited by McCormick’s grandfather, then had Churchill pegged as a “future premier of England.”

By 1940 Churchill had appeared on Time’s front cover four times, including in the magazine’s first year of publication in 1923. In 1941 its proprietor Henry Luce made him Man of the Year.

Not all his connections were made Stateside. McCormick was a reporter for the Chicago Tribune when they were introduced in London in 1915, while Churchill was Lord of the Admiralty. But his visits to the country were spiritual voyages into the future, into the centre of what Churchill would later call “the Anglo-Saxon” world. “A great, crude, strong, young people are the Americans,” a twenty-one-year-old Churchill wrote to his brother in 1895, on his first visit to New York, “who moves about his affairs with a good-hearted freshness which may be the envy of older nations of the earth.”

The same could have been said of Churchill himself, dotting about the country on speaking tours, networking with steel magnates and bankers, and telling jokes about the idiocy of Prohibition to packed music halls in Chicago and Chattanooga. Stelzer’s account reveals a hustler who was unafraid to have his image prostrated to the public and to use every connection “as a springboard, not a sofa.” On first meeting Churchill in the 1903, British Fabian Beatrice Webb famously said he resembled “the American speculator more than the English aristocrat.” Churchill’s supposed Americanism would haunt him later in his career when his colleagues considered too ambitious and too pushy.

Much of the new source material for the book comes from the American press, at times sycophantic in its devotion to Churchill. Not every American was impressed. Franklin Roosevelt, who first met Churchill in London in 1919, recalled him being “a stinker” (according to Joseph P. Kennedy, hardly an unbiased source). Elements of Churchill’s Toryism, and his occasionally mumbling, aloof style, did not always charm. Stezler’s work nonetheless helps explain a man whose appetite for risk, and whose relative lack of inhibition or shame, was at times better nurtured in the caustic atmosphere of Prohibition America than in Edwardian Britain.

Recalling the moment he became Prime Minister in 1940, Churchill said he felt he was “walking with destiny,” that “all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.” For most British Prime Ministers, the special relationship is diplomatic artifice. For Churchill, it was the apotheosis of a forty-year courtship with America and with Americans – one which proved crucial for his and his nation’s survival.

Oliver Rhodes was a Henry Fellow at Harvard University from 2022 to 2023. He previously studied an MPhil and BA in History at the University of Cambridge.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.