Bulletin #182 — Jul 2023

Churchill to a Beat

June 27, 2023

Winston Churchill in the Lyrics of Popular Music

By Teresa Dalton and Greg Dhuyvetter

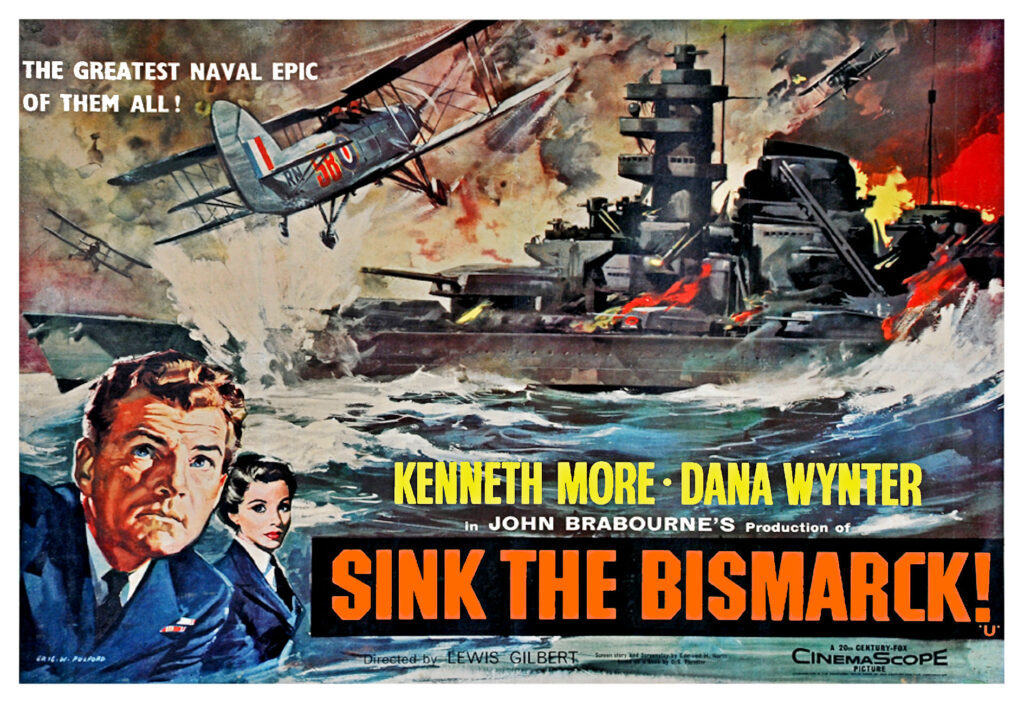

It all began with the Bismarck—specifically the sinking thereof. While cruising one morning in the music land that is Spotify, we found ourselves listening to Johnny Horton’s 1960 warhorse Sink the Bismarck and were surprised to remember that Churchill makes a cameo appearance at the half-way point of the song. This accidental discovery led to what at the time seemed to be two simple questions, “How many other popular songs mention Churchill?” and “Do these songs paint Churchill in a positive light, or is he remembered for his all-too-human imperfections?” For researchers, however, there are no such things as simple questions (particularly when you know virtually nothing about the subject), as we were soon to learn on our path down the complex rabbit hole of “WSC in dancing shoes.”

Methodology

The search began with the query, “all songs with Winston Churchill in the lyrics” producing a list of eighty-seven (and about a million non-existing songs proffered up by ChatGPT). We decided to limit our search to songs written after Sink the Bismarck in order to avoid wartime anthems, which we felt would be a different study. Each song, performer, and mention of Churchill was cross-checked with various lyric websites and/or with Spotify. Analysis was conducted on the twenty-two songs meeting the following criteria:

2024 International Churchill Conference

- the name “Winston Churchill” or “Churchill” was directly in the lyrics (there were several songs that included quotes from Sir Winston, or even his voice, but these were studies for another day)

- the song lyrics could be found on more than one website

- the lyrics were in English

See the table accompanying this articled for the full list of the songs we found along with the link to a Spotify playlist of all available tunes.

There is almost no end to the number of ways one could build thematic groupings for these songs. We begin by identifying a few general characteristics. The greatest number of times Churchill is mentioned in any one song is nine, while seventeen songs mention him only once. The longest song to make the list is twenty-three minutes; the shortest one is a mere 150 seconds. Coincidentally, the shortest song is also the one with nine mentions of Churchill. Out of the twenty-two songs, ten had Churchill-positive lyrics, eight were negative, and four were neutral. Along with Churchill, there were other notable individuals mentioned in some of these songs: Douglas MacArthur, Gene Autry, John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Noël Coward, Sherlock Holmes, Petula Clark, Beatrice Potter, Buddha, Vera Lynn, Richard Burton, Himmler, and Jesus Christ.

Diving through these surface comparisons, we moved on to the more interesting aspects of these songs as we conducted content analyses. Through this process of grouping, regrouping, and degrouping, we identified three categories:

- Churchill cited within a historical context

- Churchill’s name and reputation used symbolically

- Outliers, not conforming to either of the first two categories

A note about the analyses that follow: we focused on the Churchill citing, rather than the broader meaning of the song, and also, recognizing that there is seldom one correct meaning for song lyrics, we willingly agree that ours is not the only legitimate interpretation. We invite future discovery.

Historical Context

A number of songs with both positive and negative approaches to Churchill the man, set the name in a historical context, referring to actual actions and words of Churchill’s time. The story song Sink the Bismarck (where this whole quest started) is the most historically referential. Churchill implores the soldiers to do whatever they can to “sink the Bismarck to the bottom of the sea.” The song is a reenactment of actual events in which Churchill is portrayed as the wise leader recognizing the need to eliminate this most powerful and destructive German warship. His order is seen as a positive, society-affirming act, and the loss of 2,000 lives a strategic success, “We had to sink the Bismarck ’cause the world depends on us.” Not all songs, however, reference Churchill’s military decisions similarly, some viewed his actions unfavorably.

The words, orders, and approach toward war are portrayed quite differently in Jona Lewie’s 1980 protest song Stop the Cavalry and the Kinks’ 1969 protest melody Mr. Churchill Says. Both of these songs weigh the military optimism portrayed in Sink the Bismarck against the true cost to individuals and to countries. Stop the Cavalry begins with Churchill speaking to soldiers, praising them, and telling them how well the war is going: “Mr. Churchill comes over here / To say we’re doing splendidly.” The rest of the song, however, told in the voice of a soldier, tells a very different story: “But it’s very cold out here in the snow / Marching to and from the enemy.” As the song continues, the speaker becomes emblematic of all soldiers destined to fight and die for others’ “splendid” success. Mr. Churchill Says is a close parallel, with the optimistic encouragement of Churchill, “Mr. Churchill says / We gotta fight the bloody battle to the end,” contrasted with the real costs of such warfare, “Did you hear that plane flying overhead? / There’s a house on fire and there’s someone lying dead.” In both of these songs, the cost of Chuchillian optimism is shown as a dire parallel to the current conflicts when each song was written.

In the two remaining songs of this section, other words of Churchill are shown to have effects on lives and minds. The ska band The Specials’ B.L.M. tells the story of the speaker’s father, who heard Churchill extending an invitation to all parts of the empire: “Sir Winston Churchill shout across the Western Islands / He said ‘Come help us rebuild this country devastated by war.’” But rather than bringing a shining future, this invitation leads to generational devastation of a family which heeded this offer only to discover the dismal conditions available to non-Brits in post-war England: “No dogs, no Irish, no Blacks / Welcome to England.” Graham Parker’s Protection begins with a quote attributed to Churchill as a starting point for an exploration of love and loss: if “all you be damned, we can’t have heaven crammed.” There is no safety and no happy ending for anyone. Parker positions Churchill as the truth teller, the one who recognizes the pain of existence. This general loss of security is broadened as the song continues to discuss the loss of love which is “The knife in the heart that tears you apart.” While apparently referring to a historic quote heard by the artist, the speaker of Protection, takes the words of Churchill beyond their intended context further than any of the other historical songs, as the leader giving orders in Bismarck is now giving private messages to the artist.

Symbolic Use

The largest number of songs only vaguely refer to Churchill’s historical actions. Rather, they use the name as an icon or metaphor, both positively and negatively, to advance the primary theme of each song.

Three songs in this category use Churchill as a symbol of the glorious past of England and the West. Ian Dury’s England’s Glory is a listing song; that is, he positions Churchill with a host of other famous names. He includes Churchill as one more of the “jewels in the crown of England’s glory,” stacking him with real and fictitious heroes of the realm. Churchill is used far more directly in Ian Hunter’s Death of a Nation. The song describes Churchill as an almost Arthurian figure in a dream, castigating the current path of the country: “look what they’ve done, it’s the death of a nation.” This type of lionizing of Churchill as an emblem of British strength and hyper masculinity is seen most clearly in Bill Andersons’s Where Have All Our Heroes Gone? This song offers Churchill as a model for young boys to fight for victory and “Not just let-your-enemy-have-it-all kind of artificial peace.” The name and reputation of Churchill is assumed to have power to inspire, even in a fallen world.

The positive portrayal of Churchill depicted in the songs described so far differs from that represented in a number of songs that refer to Churchill in dismissive, disrespectful, and mocking ways. Peter Frampton’s Thank You Mr. Churchill, from the album of the same name, expresses gratitude to Churchill for “making sure that I was born” presumably through his actions and decisions during the war. The rest of the song, however, advocates a new way, moving past the violence of war into a world of peace and help for the poor. The thanks to Mr. Churchill are qualified and dismissive. Churchill’s name and image also fare poorly in the Kinks’ Supper’s Ready, where on successive lines Churchill, as the symbol of a fallen Britain, is described as, “dressed in drag,” “a plastic bag,” and “The frog [that] was a prince.” The glory of the past, as represented by Churchill has become tawdry and diminished. This mockery becomes overt in the Fall’s nearly incomprehensible Tempo House. Churchill is ridiculed for his “speech imp-p-p-p-pediment” and his actions: “Look what he did / He razed half of London.” This mockery is complete in Eels’ Your Lucky Day in Hell, where a female character is described as “Winston Churchill in drag.” This is the second reference to Churchill in drag from among the twenty-two songs. It is not a comment on his character but rather a direct assault on his looks as the epitome of female unattractiveness. Whether seen as a worn-out relic of the past or a subject of overt mockery, songs use the name Churchill for what it represents in the mind of the songwriter and the hearts of the listeners.

Some artists have taken this symbolism to a heightened level of inveighing: Winston Churchill as a destructive force. In Wardance and Oliver’s Army, Churchill becomes a symbol of jingoistic Britain. The resurrection of Churchill is associated with “power and glory fever” in Wardance, which underlies the premise that sentiments of Churchill’s time are being brought back to destroy young people. After all, it is young people who will be asked to fight the wars and risk sacrificing their lives. In a similar manner, Elvis Costello sings of anti-military sentiment in Oliver’s Army. This now infamous song from 1979 brings the horror and brutality of war into focus: “He didn’t crack a smile / But it’s no laughing party / When you’ve been on the murder mile.” Churchill is used a symbol of the British machine: “Just a word in Mr. Churchill’s ear.” The famous war leader represents the force behind mobilization of the British military in hotspots all over the world. In each of these songs the name Churchill is synonymous with senseless military destruction.

Churchill fares better with rappers and their lyrics. His name is used, not only for the number of syllables it contains and their rhyming characteristics, but also for symbolism in two rap songs. In Freeman, Churchill is drawn upon for the character he represents: “And I speak with chest and I keep it real and I lead like Winston Churchill.” Here we see the song’s protagonist building himself up with his similarities to this iconic figure while also stating, “I don’t chase clout and I don’t chase hoes,” truly noble qualities to which one should aspire. In a similar manner, the rapper Catfish refers to Churchill in Little Kid as having “dark mind bright but a pretty bright soul.” This identification with Churchill continues as he states that, like Churchill, he will never surrender. One has to wonder how Churchill, if alive today, would react to being part of the rap scene.

Finally, when reviewing songs with Churchillian symbolism, we have two that speak to aspects of Churchill’s personal struggles. Churchill’s own metaphor of “black dog” for depression makes its way into song lyrics as well as his name. In Charlie Penn’s It’s All about Winston Churchill, the title refrain is repeated nine times, while the speaker talks about his life coming apart due to loss of love. The speaker states multiple times, “The big black dog will move on when I’m gone.” In other words, depression will clear after the current crisis. This is more than a mere nod to Churchill’s life, it is a direct association with his emotional burden. In a similar manner, Manic Street Preacher’s Black Dog on My Shoulder uses the name of Churchill only to identify the metaphor for the exploration of the speaker’s own despair: “Black dog’s a-coming tonight / My dilemma but not my choice / Winston Churchill, can you hear my voice?” While there is nothing unique in a song about depression, these artists use a controlling metaphor, identified with a wink to the cigar-smoking depressive.

Outliers

While most of the songs analyzed fall into the above two categories (historical and symbolic) there are a handful that evade categories yet are nonetheless important as we seek to understand the public sentiments captured by song artists. The first to consider is Quicksand byDavid Bowie. In traditional Bowie style, this song moves from the mystical to the earthly: “Of imagery I’m living in a silent film….Can’t take my eyes from the great salvation / Of bullshit faith.” Churchill fits in among those Bowie rails against: Himmler, Homo Sapiens, prophets, Man— “Living proof of Churchill’s lies.” Churchill is both a person and a myth. In A Somewhat New Medium, the artist ironically juxtaposes a quote on a sign, “Americans are slow to hostility,” attributed to Churchill with the bizarre scatological reality of a bird’s feces on someone’s shirt. This is, however, a misquote. The original statement by Churchill was, “There are no people in the world who are so slow to develophostile feelings….” Slight errors in the quote notwithstanding, Churchill seems to be a placeholder for any serious leader in both songs; just about any influential world leader may have worked. This remains true for the other outlier songs: there is no particular link to Churchill with the exception of his name being used yet each of the following songs bring a fresh new way to consider the man.

Taking Churchill (and his name) in decidedly unique directions, we find two songs: I Like Sikhs and (You & Me and) Winston Churchill. In both the artists invite the listener to recall Churchill but for quite different reasons. For You & Me it is about a fanciful life that could include Churchill. For Sikhs, it is written with a kind of warning that we must not forget this important world leader. (You & Me and) Winston Churchill situates Churchill as one of three friends, experiencing life: picnicking, drinking, getting a home together, going to a rave party, getting a dog. This song is upbeat, the three friends come to appreciate each other’s friendship and that of a dog who “will grow into your best friend you can depend.” The image of Winston Churchill at a rave, with the attendant drugs and glowsticks, keeps this song lighthearted. This friendship song appears to be intended as a positive view of Churchill, a guy with whom one could party. I Like Sikhs seeks to defend Churchill from possible censure, keeping his name and reputation alive. Sikhs, a song from 2021, provides a list of what the artist refers to as “irrational rants of affection,” as he welcomes the listener to the “snowflake generation.” Inclusion in the list seems to suggest a canceling that has either already occurred or is likely to happen. The artist “likes”: Scots, postal carriers in shorts in cold weather, Gavin & Stacey, Goths and Geeks, Hare Krishnas, statues, massive Afro hair, and Churchill, to name a few. Churchill would probably be proud to be included in this inventory: positioned as an important figure to be remembered, imperfect as he was.

From rap to county, from folk to rock, Sir Winston Churchill continues to live in the lyrics of popular music long after his death. His presence (and the interesting ways it is used) not only speaks to his ongoing importance in Britain and throughout the West, it also provides comment on the nature of art and song. Cultural icons, such as Churchill become the vocabulary and shorthand of popular art, moving society forward while sometimes looking backwards.

Teresa Dalton, Ph.D. is Professor of Teaching at the University of California, Irvine. Gregory Dhuyvetter, MA is Executive Director of Western Catholic Educational Association.

* * *

The following is a list of all songs mentioned in this article, along with artists and year of recording. It is important to note that a number of these songs do (or would) earn the E rating (explicit lyrics) on Spotify, so beware. A Spotify playlist of all available songs can be found at: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/3rWFve60GstcO43QONApIH?si=0zOA36e3SLGevtL_swGExg

| Name | Artist | Year |

| A Somewhat New Medium | MC Paul Barman | 2002 |

| B.L.M. | The Specials | 2019 |

| Black Dog on My Shoulder | Manic Street Preachers | 1998 |

| Death of a Nation | Ian Hunter | 2001 |

| Freeman | M1Liter | 2022 |

| England’s Glory | Ian Dury | 1996 |

| I Like Sikhs | Phil Goodman | 2021 |

| It’s All About Winston Churchill | Charlie Penn | 2021 |

| Little Kid | Catfish | 2017 |

| Mr. Churchill Says | The Kinks | 1969 |

| Oliver’s Army | Elvis Costello | 1979 |

| Protection | Graham Parker | 1989 |

| Quicksand | David Bowie | 1971 |

| Sink the Bismarck | Johnny Horton | 1960 |

| Stop the Cavalry | Jona Lewie | 1980 |

| Supper’s Ready | Genesis | 1972 |

| Tempo House | The Fall | 1998 |

| Thank You Mr. Churchill | Peter Frampton | 2010 |

| Wardance | XTC | 1992 |

| Where Have All Our Heroes Gone | Bill Anderson | 1994 |

| (You & Me and) Winston Churchill | Pagan Wanderer Lu | 2009 |

| Your Lucky Day in Hell | Eels | 1992 |

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.