Bulletin #153 — Mar 2021

Churchill & Islam

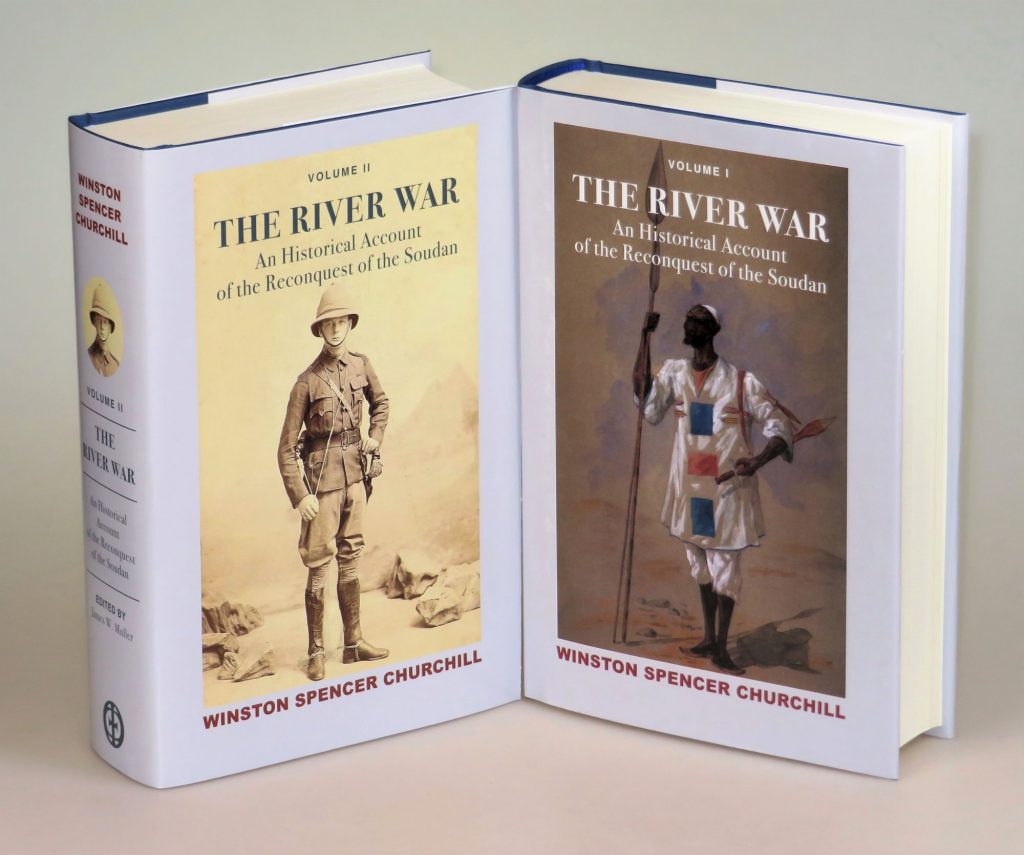

Photo: The Churchill Book Collector

February 27, 2021

By JAMES W. MULLER

The long-awaited definitive edition of Winston Churchill’s book The River War has now been published. The roots of the conflict in which young Lt. Churchill charged with the 21st Lancers at Omdurman went back to a revolt in Sudan initiated by the Mahdi, a charismatic leader in the Muslim world. The newest issue of Finest Hour explores the subject “Churchill, Race, and Religion” and includes the observations of the Mahdi’s grandson about how the River War affected Churchill. In his introduction to the new scholarly edition of The River War, editor James W. Muller also examines how Churchill’s views about Islam were formed by his early experiences in Asia and Africa. Here follow extracts.

In The River War, Churchill calls Islam “Mohammedanism” and Muslim law “Mohammedan,” terms used by analogy with “Christianity” and “Christian” and more in favor among non-Muslims than among Muslims, who see them as misnaming Islam and the Muslim faithful as if Muhammad were analogous in Islam to Christ in Christianity. In fact, for Muslims the Qur’an as God’s word is the better analogy to Christ for Christians; in Islam true religious devotion belongs to God, who is divine, not to his Prophet, who is human, and whose followers therefore worship not Muhammad but only God. Few would be glad to think that they were fanatics.

The effects of both the “frenzy” and the “apathy” Churchill imputes to Muslims are hardly complimentary. He finds them in the thrall of “a degraded sensualism,” spoiling their lives both in this world and the next. He argues that they confuse women and slaves with property. Despite his acknowledgment that “individual Moslems may show splendid qualities,” that thousands of Muslims are “brave and loyal soldiers of the Queen,” and that all Muslims “know how to die,” he judges them paralyzed in their “social developement” and Islam the strongest “retrograde force…in the world.”

But Churchill did not write to curry favor with Muslims. He may indeed have hoped to sow seeds of doubt about their religion in the minds of some readers—whether they were Muslims or not. He was certainly trying to explain Islam to readers most of whom were not devout Muslims and had no particular sympathy with that religion. Churchill’s critique of Islam is based on his reading and on his observation of the Muslims he had encountered in India and on the Nile. If, instead of shying away from his words out of a wish to conform to a current notion of what is politically correct, we look squarely at his argument, we see that he considers the religion a curse to its votaries because it leads them either to superhuman confidence that they will be saved if they die fighting for God—“fanatical frenzy,” as Churchill describes it—or to diffidence that makes them practically inert, relying on God alone to look after them—“fearful fatalistic apathy,” in Churchill’s words.

Churchill had seen frenzy in the Muslims’ way of warfare both in India and in the Sudan: Pathans and Dervishes alike are inclined to fight to the death for their God, certain that if they are killed they will go to paradise. One sees the effects of this propensity, he thinks, in the fact that, while “nearly all civilised soldiers sit down when they are severely wounded,” Britain’s opponents in her little wars against devout Muslims have “to be hopelessly disabled before they admit their injury” and give up the fight. He likens their behavior to hydrophobia because he does not think it reasonable for human beings to be so indifferent to their bodies as to fight on, even when severely wounded, because they have faith in another life to come. Yet a prudent man might risk his life to defend his honor.

Churchill contrasts an army of soldiers “following their officers in blind ignorance” with an army of civilized soldiers, in which each man was “an intelligent human being, who thought for himself, acted for himself, took pride in himself, and knew his own mind,” when he describes the achievement of the Twenty-first Lancers in the cavalry charge. But Churchill does not discount the valor of his enemy either. He discerns nobility in the Dervishes who charged the British Maxim guns and “died to clear their honour from the stain of defeat”: “the Arabs who were conquered by [Britain’s Gen.] Kitchener fought in the pride of an army.”

It is inertia, on the other hand, that Churchill finds responsible for “improvident habits, slovenly systems of agriculture, sluggish methods of commerce, and insecurity of property”—all of which paralyze “social developement” of the sort that modern men account as progress. This inertia comes from submitting entirely to God—the literal meaning of Islam—and attributing everything that happens to him. It is the opposite of taking off one’s “coat to the work.” Instead of exerting themselves to think and act for themselves, rulers and subjects alike give themselves up to crude feelings—to selfish desires on a greater or smaller scale, depending on whether they “rule” or merely “live” as “followers of the Prophet.” This “degraded sensualism” leaves life on earth without the “grace and refinement” and the next life without the “dignity and sanctity” that civilization imparts to men.

The charge that Churchill makes against Islam is that Muslim law does not recognize the civilized distinction between women and physical property, which means that slavery will not end until Muslim law is replaced by a law recognizing the equal rights of all human beings. It is easier for those who are stronger to oppress those who are weaker and for those who are weaker to submit to those who are stronger, but civilization means not taking advantage of those who are weaker simply because one can and not bowing to those who are stronger simply because one must.

Lest complacent readers take their own superiority to the Muslims for granted, Churchill reminds them that Islam is strong: “No stronger retrograde force exists in the world.” He alerts them, in case they have not paid much attention to it up till now, that it is “a militant and proselytising faith” that “has already spread throughout Central Africa, raising fearless warriors at every step.” But, as the accomplishments and professed ambitions of the Mahdi and his Khalifa suggest, it respects no boundaries to its own entitlements, except the strength and superior technology of its enemies. Civilized nations that respect the rights of their weak as well as their strong citizens must maintain the strength to defend themselves against uncivilized nations that respect only strength.

Churchill warns that the survival of “the civilization of modern Europe” depends on its superior force and its confident understanding of its own superiority to “fearless warriors” who would destroy it. Those who blithely insist that no culture is better than any other and shudder at Churchill’s insensitivity to the claims of his country’s enemies when he distinguishes between civilization and savagery would have far more to shudder about “were it not that Christianity,” with its legacy of mercy to the weak, “is sheltered in the strong arms of science.” In particular, unless “the faith of Islam” that countenances a “law that every woman must belong to some man as his absolute property” is replaced by a faith and a law that recognize the rights of women, one cannot rue Churchill’s insistence on the superiority of the civilization that does recognize them. For to dismiss Churchill’s claim that the British Empire was superior to the Dervish Empire as merely a prejudice is to dismiss the rights of women in the same way.

The new edition of The River War is now available direct from the publisher, St. Augustine’s Press. To order, please CLICK HERE.

For information about the limited issue, leather-bound set available exclusively from the Churchill Book Collector please CLICK HERE. Remaining supplies are extremely limited.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.