Churchill 2024

Celebrate the 150th Anniversary of Winston Churchill's Birth

A year of events to celebrate this important anniversary.

Find Out MoreWriting, Articles & Books

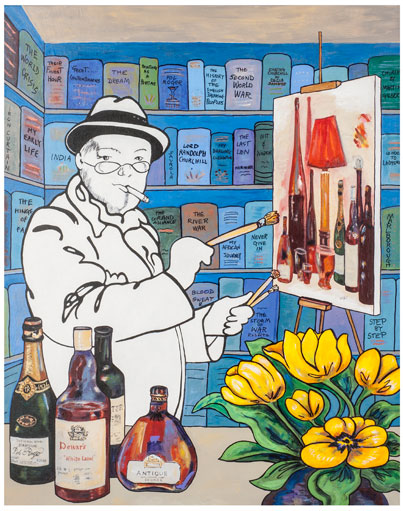

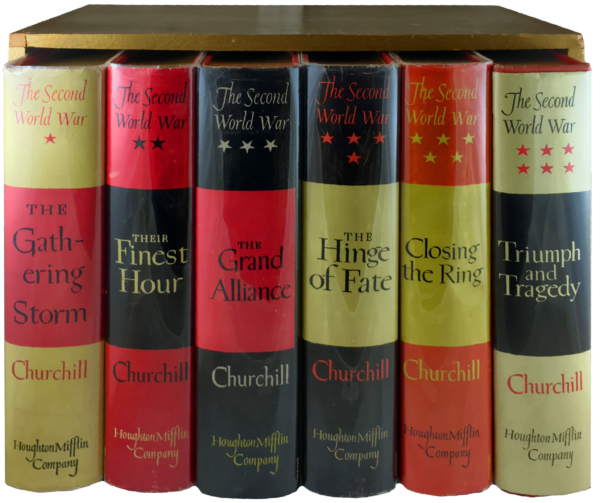

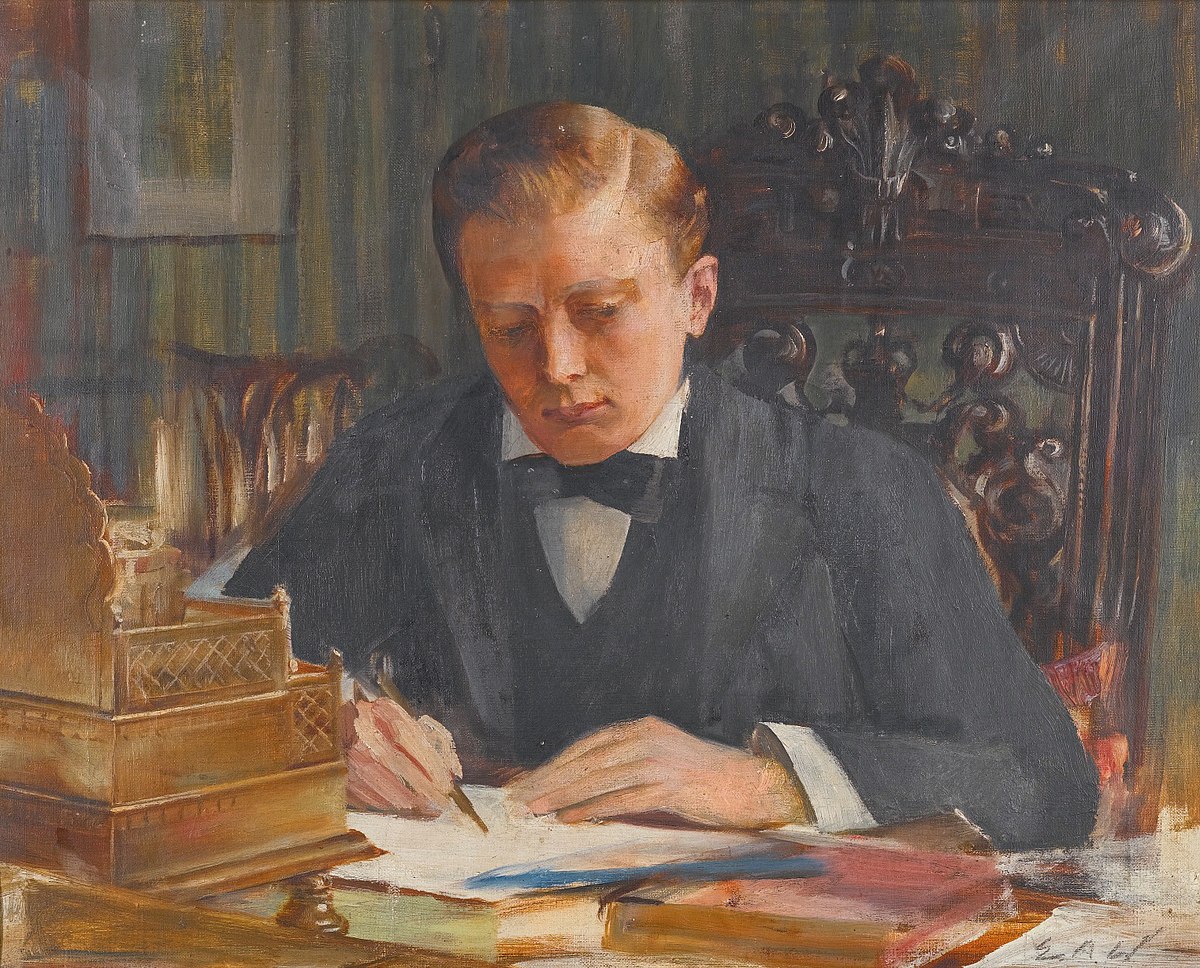

In his lifetime, Churchill published more than 40 books in 60 volumes.

View his writingYoung Churchillians

Working to celebrate the life and achievements of a great leader.

Young ChurchilliansPublications

In his lifetime, Churchill published more than 40 books in 60 volumes.

View PublicationsSubscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.