Finest Hour 189

Why Have the Scots Forsaken Churchill?

Churchill and fellow officers of the

September 21, 2020

Finest Hour 189, Third Quarter 2020

Page 08

By Alastair Stewart

Alastair Stewart is a Scottish public affairs consultant and freelance writer. His mum, granny, and grandad gave him a lifelong interest in Winston Churchill.

In the United Kingdom today, there is a debate about our history and our statues. Raised are two perennial questions: what is truth and what is an acceptable legacy? That debate has literally and physically targeted the Ivor Roberts-Jones statue of Winston Churchill in Parliament Square.

Yet Scots, forever ready for a feisty debate, are left looking around for a comparable statue of Churchill even to protest. While most communities are proud of their connections to significant historical figures, a Dundee historian has said of his city, where Churchill served as the local MP for nearly fifteen years, “A statue of Winston Churchill here would be as welcome for many as a swim through vomit.”1 Does he speak for all Scotland?

The Invisible Man

In 2019, an elected Member of the Scottish Parliament courted controversy and praise when he tweeted that Churchill was a “white supremacist” and a “mass murderer” interspersed with hand-clapping emojis.2 The shock value aside, the post quickly revealed the pantomime view of Churchill, which underpins his legacy in Scotland.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Pervasive myths continue to abound that Churchill abandoned the 51st Highland Division in 1940, set soldiers of the Black Watch on his Dundee constituency in 1911, sent tanks into Glasgow in 1919, and would have abandoned Scotland if Nazi invasion had come in 1940. (See the following article.)

Of course Churchill said things that are distasteful to modern sensibilities; he was born in the age of the cavalry charge and died when the Beatles were at their zenith. Issues on race, women’s suffrage, and Irish Home Rule are all topics that have to be contextualised to be understood.

But Scots are unlikely to be convinced. Social media, sound bites, and ferocious campaigns for Scottish independence and Brexit have bled nuance dry. Churchill is either a bogeyman or a hero, a visceral stand-in for debates on Scottish unionism, or British and Scottish nationalism—usually in 280 characters.

In Dundee, there is barely any acknowledgement that Churchill was there at all. In the lobby of the Queen’s Hotel, there is a plaque commemorating his campaign headquarters that went up in 2008. There is also a copy of a letter he sent to Clementine, famously complaining about a maggot in his kipper that “flashed his teeth.”3

The formal Dundee acknowledgement is dire: there is one plaque. Unveiled in 2008 by Churchill’s daughter Lady Soames, the marker commemorates the centenary of Churchill’s first election to Parliament from the city in 1908. It has now been vandalised.

There are a smattering of other tributes to be found to Churchill in Scotland, including a bust in the City of Edinburgh Council building and a Churchill suite in the capital’s Prestonfield Hotel. At the Dalmeny Estate, the family seat of the Earldom of Rosebery (see story on p. 20), there is a tree planted by Churchill in 1946. And in the Edinburgh Central Library there is a plaque honouring suffragist Elsie Inglis that includes a tribute from Churchill reading, “She will shine forever in history.”4

In Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, there is a four-foot bronze figure of Churchill by Scots sculptor David McFall. This is a smaller version of the full-size statue erected in Churchill’s former constituency of Woodford in 1959. In the Orkney Islands, Willie Budge’s 2011 monument to the Churchill Barriers at Scapa Flow (see story in FH 171) is, rather aptly, just a shadow of Churchill made from a rudder.

It is impossible to pronounce in absolutes, but observation, particularly of social media, reveals several core explanations and myths, which reinforce general Scottish despondency over Churchill. First, there is the recurring belief that Churchill simply did not care about, or was at least indifferent to, Scotland. Second, Churchill is seen to have tried to suppress Scottish strikes, an extension of perceived English and aristocratic suppression of the Scottish working class.

Third, the case for Scottish independence is nearly always made in reaction to the British state, Brexit, and British history (of which Churchill is a giant). Fourth, the prevalence of social media, in tandem with the absence of a single source or leading voice speaking about Churchill and Scotland, has allowed grievance politics to fill the void. Fifth, modern Scottish education generally focuses on the deeds of empire, including slavery and colonialism, with no broader context for the time. This moral rigidity makes even passing support for the British Empire or Churchill taboo and implicitly racist.

Troubles Left and Right

There is a persistent myth that Scotland is more left-wing than England. Repeated polls cannot give a definitive answer. “Left-wing about what?” would be a better retort—one can be socially liberal and a hawk on defence without tautology. Still, Scottish exceptionalism is a normative and predominantly nationalist ideology about being a “good global citizen.”5 Scotland is implicitly placed as morally superior to the UK Government, the British Empire, and Churchill.

And yet Scotland, in partnership with England since 1707, built the British Empire. At one stage, Scots were estimated to comprise one-third of all imperial governors.6 Scots provided vast numbers of traders, administrators, and pioneers, who took a considerable share of the imperial spoils.7 The extraordinary influence of Scots at nearly all levels of the empire makes today’s “acute case of cultural amnesia” all the more puzzling.8

Popular history is a supply and demand industry. The popularity and awareness of Scottish tragedies such as the Highland Clearances have bolstered the politics of grievance. Scottish education has never corrected the public imbalance and focuses disproportionately on episodic wars with England led by William Wallace and Robert Bruce. Empire receives perfunctory attention, at best, despite Scotland’s central role (Dundee, for example, was the “Juteopolis” of the empire).9 Churchill, long taken for granted alongside unionism, has fallen out of favour and is now cast as the villain—much like the United Kingdom itself.

Many have noticed the dichotomy between Scottish sentimentalism and rationalism.10 The Scottish National Party (SNP) has been in power in Scotland since 2007 and has taken the majority of Scottish seats at Westminster since 2015. Yet the independence referendum held in 2014 was defeated 55% to 45%.

Since the referendum, Churchill—the epitome of British and English identity—has become the chief bogeyman. In particular, “Cybernats,” the unofficial, online foot soldiers of independence, have put Churchill in their crosshairs over the last decade. Not to be outdone, unionist trolls have made Churchill a reactionary poster boy to independence arguments.

The reasons are not just the lack of education and the prevalence of social media, but the disproportionate number of young people now involved in political discourse. Scotland lowered the voting age to sixteen during the referendum, and most SNP voters were under forty at the 2019 general election. Concurrently, successive polling has shown that most UK students do not know who Churchill was or think he has been made up.11

The broader debate around statues that has now emerged compounds existing problems. Headlines reinforce falsehoods because Churchill’s life is not taught correctly in schools. He has been reduced to his repertoire of bon mots, both real and false, that may have passed into common parlance but which reinforce misperceptions. Scots left, right, and centre hold popular misconceptions about Churchill.

Many think of Churchill as an entertaining drunk, despite evidence to the contrary. Some consider him representative of his aristocratic background, not knowing that as a young MP he was considered a traitor to his class for helping to found the welfare state. Others say he was a warmonger and murderer, unaware that in 1916 Churchill led Scottish troops in the trenches, an experience that led to his opposition to a premature cross-channel invasion during the Second World War, which would have resulted in mass slaughter.

Ironically, even some of Churchill’s defenders in Scotland rely on an untruth by frequently citing one of the most famous remarks Churchill never made: “Of all the small nations of this Earth, perhaps only the ancient Greeks surpass the Scots in their contribution to mankind.” The quote flourishes but with no source— like many myths in the digital age.

Why Scots Should Put a Kilt on Churchill

The £12 billion tourism industry is important to Scotland. Playing up the many Churchill connections could only enhance this. There is even a genuine picture of Churchill sitting in a Glengarry bonnet (above). Yet despite a smattering of Churchill busts and portraits spread across the country (notably the one on the cover of this issue), there is no mad dash to take full advantage of Churchill’s extensive connections with Scotland. When actor Brian Cox—a Dundonian himself—played Churchill in a 2017 movie filmed in Edinburgh, the event passed with barely a flutter of excitement. The closest one comes to finding Scottish tourism playing up Churchill is a “Fortress Orkney” site-seeing map.12

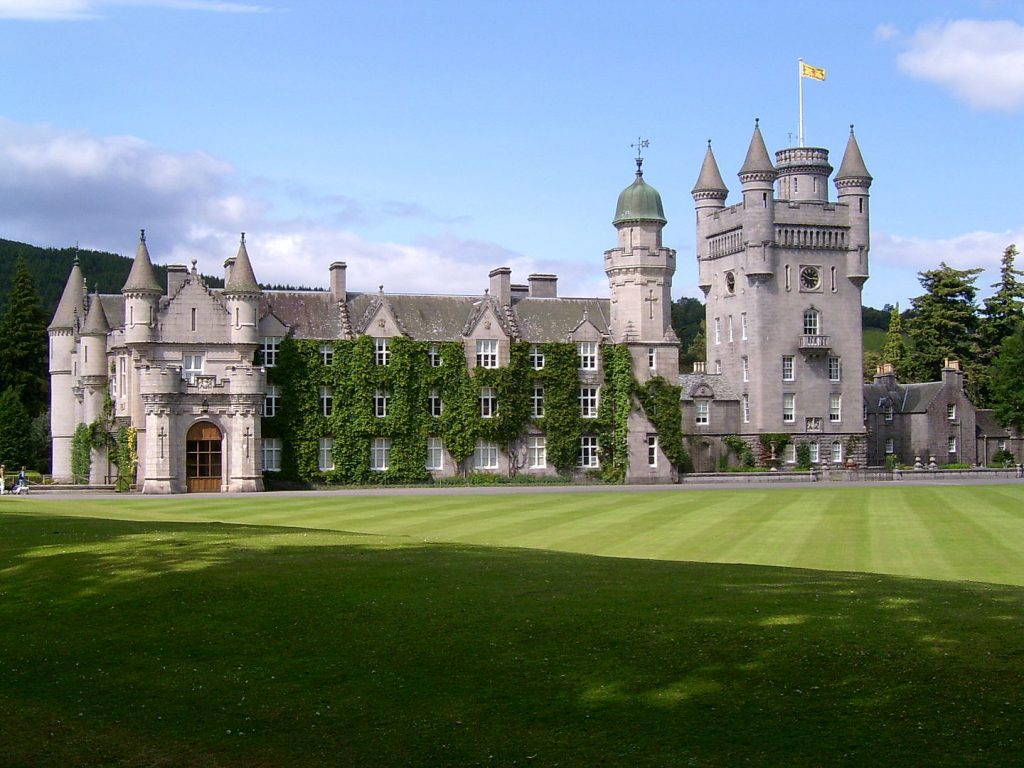

But there is so much that could be done! In addition to those already mentioned, there are many other connections between Churchill and Scotland; his wife Clementine was of Scottish descent, a granddaughter of the 10th Earl of Airlie; his aptly named first biographer, Alexander MacCallum Scott, was Scottish; he made frequent trips to Balmoral to attend upon the Sovereign; he served as Rector of the University of Edinburgh in 1929; he formed the Commandos from Scotland in 1940 and ordered the creation of the Scapa Flow bridges that same year.

Churchill’s son Randolph even (unsuccessfully) contested the Ross and Cromarty by-election in 1936. There is also an emotional matter to consider that has not been examined: Churchill mourned his daughter Marigold in Scotland shortly after her death in 1921. The saga, then, is replete with anecdotage, anger, joy, sorrow, and adventure. Churchill losing his Scottish seat in 1922 to a prohibitionist candidate is the grandest of punchlines.

And then there is the military history: Churchill’s substantial connections with Scotland during the two World Wars (see story on p. 26). During the First World War, Churchill commanded the 6th Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front. His Adjutant was Andrew Dewar Gibb (a future Leader of the SNP), who wrote a book about the experience. Gibb recorded Churchill saying to his troops that, “Although an Englishman, it was in Scotland that I found the three best things in my life: my wife, my constituency and my regiment.”13 Churchill’s second in command was Archibald Sinclair, who went on to become the Leader of the Liberal Party and a member of Churchill’s coalition government starting in 1940. During the Second World War, Churchill proposed a meeting with Roosevelt and Stalin and suggested Invergordon as a venue: “the weather might well be agreeable in Scotland at that time.” The US president declined.14

More successfully, during the war Churchill appointed a Scot, James Stuart, to serve as Chief Whip. Churchill’s four Scottish secretaries of state during the war represented all of the major parties of government: David John Colville (Conservative MP and not to be confused with Churchill’s Private Secretary John Colville, himself the grandson of a Scottish peer), Ernest Brown (Liberal), Thomas Johnston (Labour), and the 6th Earl of Rosebery (Liberal).

When trying to persuade Tom Johnston to join his government, Churchill proclaimed, “Good heavens, man, come in here and help me make history!”15 The Prime Minister picked Johnston because he was left-wing and could help prevent a repeat of the Red Clydesdale disruption that occurred during the First World War.

The Second World War has also generated at least one example of Scots trying to prove a connection with Churchill that may not be true but would be good for tourism. In 2019, the BBC reported that the Prime Minister purportedly held a secret meeting in Scotland with General Eisenhower in 1944 to discuss the D-Day landings.16

There are today Churchill connections good for Scottish trade, including his preference for Johnny Walker whisky, Drambuie liqueur, Dundee cake, and Scottish grouse. He even considered purchasing a small estate near Edinburgh before buying his lifelong home of Chartwell in Kent in 1922.

And where are the books? While there have been many articles and essays published about Churchill in Scotland over the years, including one book about his time in Dundee, there has yet to be even one dedicated volume about Churchill and the Scots. The omission teeters on the bizarre, given the vast library of books on seemingly every facet of Churchill’s life.

Despite all of the opportunities, however, the Scots themselves have done little to stake their many claims to Churchill.

The Saltire Bulldog

So, are there any ways for Scots to think of Churchill as one of their own? Yes, many.

First, Churchill sincerely cared about Scotland. During his time as a Scottish MP, he served in a series of senior ministerial posts: President of the Board of Trade, Home Secretary, First Lord of the Admiralty, Minister of Munitions, and Secretary of State for both War and Air. All of these ministries deeply involved Scotland. In a 1942 speech in Edinburgh, Churchill reflected that “I still preserve affectionate memories of the banks of the Tay.”17

Churchill was, in fact, the original nationalist—and a federalist. Unionism and nationalism were always complementary and interchangeable forces in Scotland for the first part of the twentieth century—and Churchill knew this. As early as 1913, he looked forward to the day “when a federal system will be established in these Islands which will give Wales and Scotland the control within proper limits of their own Welsh and Scottish affairs.”18

A YouTube search for “Churchill and Scotland” yields a trove of British Pathé videos now generally forgotten. Some of the best footage is from 1942, when Edinburgh authorities bestowed the Freedom of the City on Churchill (an honour he also accepted from Aberdeen, Ayr, Perth, and Stirling). Admittedly, he turned down the same honour from Dundee in 1943. Rejection is hard to forget (see story on p. 32).

Should Auld Acquaintance Be Forgot?

Why, then, Scotland’s persistent rejection of Churchill? Part of the problem is that he is considered an exclusively English figure. His daughter Mary Soames summarized it best in a letter to her father in his final years: “I owe you what every English man, woman and child does—Liberty itself.”19

Scots are no more cognitively dissonant about their history than any other country, but the UK is confused. Devolution is not mutually exclusive with British identity, but there is an undoubted scramble for the future that struggles to explain figures like Churchill.

In an effort to promote Scottishness, we risk cutting ourselves off from our rich shared tapestry—including Winston Churchill. The rise in English nationalism (fuelled by the absence of its own devolved and exclusive assembly) is as much a challenge to pride, and history, in the UK’s story.

But Britain is a colossus. Churchill’s time in Scotland and his story with our nation is so much more than the simplistic view of him as a “carpetbagger” who needed a constituency.20 In 1936, the Edinburgh Evening News wrote that Randolph Churchill’s Scottish by-election defeat “seems to be regarded as another nail in the political coffin” of his father.21 Scotland has been wrong before and needs to fix its relationship with Churchill. There is more to Scotland and Churchill than people know. Churchill happily borrowed from Charles Murray when he told his 1942 Edinburgh audience: “Auld Scotland counts for something still.”22

Endnotes

Note: All website references were accessed 25 June 2020.

1. Michael Alexander, “Is It Time for Scotland’s ‘Racist’ Statues to Be Torn Down or Has ‘Political Correctness’ Gone Too Far?” The Courier.co.uk, 13 June 2020.

2. Ross Greer, https://twitter.com/ross_greer/status/1088871720382091264?s=20

3. Mary Soames, ed., Speaking for Themselves: The Personal Letters of Winston and Clementine Churchill (Toronto: Stoddart, 1998), p. 32.

4. https://www.edinburghchamber.co.uk/war-hero-and-suffragist-dr-elsie-inglis-honoured-atcentral-library/

5. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-future/

6. Andrew Mackillo and Steve Murdoch, Military Governors and Imperial Frontiers c. 1600–1800: A Study of Scotland and Empires (Leiden: Brill, 2003), p. xxxiv.

7. T. M. Devine, Scotland’s Empire: 1600–1815 (London: Penguin, 2012).

8. T. M. Devine, Scotland and the Union: 1707–2007 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), p. 113.

9. https://edinburgh.universitypressscholarship. com/view/10.3366/edinburgh/9780748686148.001.0001/ upso-9780748686148

10. Carol Craig, The Scots’ Crisis of Confidence (Argyll: Argyll Publishing, 2011), p. 36.

11. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/ news/uknews/1577511/Winston-Churchill-didnt-really-exist-say-teens.html

12. https://orkneyuncovered.co.uk/ fortress-orkney-multi-day-wartime-tour/?doing_wp_cron=159312 0519.8651900291442871093750

13. Andrew Dewar Gibb, With Winston Churchill at the Front (Yorkshire: Frontline Books, 2016), p. 136.

14. http://digicoll.library.wisc. edu/cgi-bin/FRUS/FRUS-idx?type=turn&id=FRUS. FRUS1944&entity=FRUS. FRUS1944.p0028&q1=invergordon

15. Tom Johnston, Memories (London: Collins, 1952), p. 148.

16. http://www.bbc.com/travel/ story/20190604-the-top-secretmeeting-that-helped-win-d-day

17. http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/policy/1942/421012b.html

18. https://digital.nls.uk/churchill/ intermediate2.html

19. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, Vol. VIII, Never Despair, 1945–1965 (London: Heinemann, 1988), p. 1366.

20. Tony Patterson, Churchill: A Seat for Life (Dundee: Winter, 1980).

21. Edinburgh Evening News, 13 February 1936.

22. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=dAFZr1MVjF4

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.