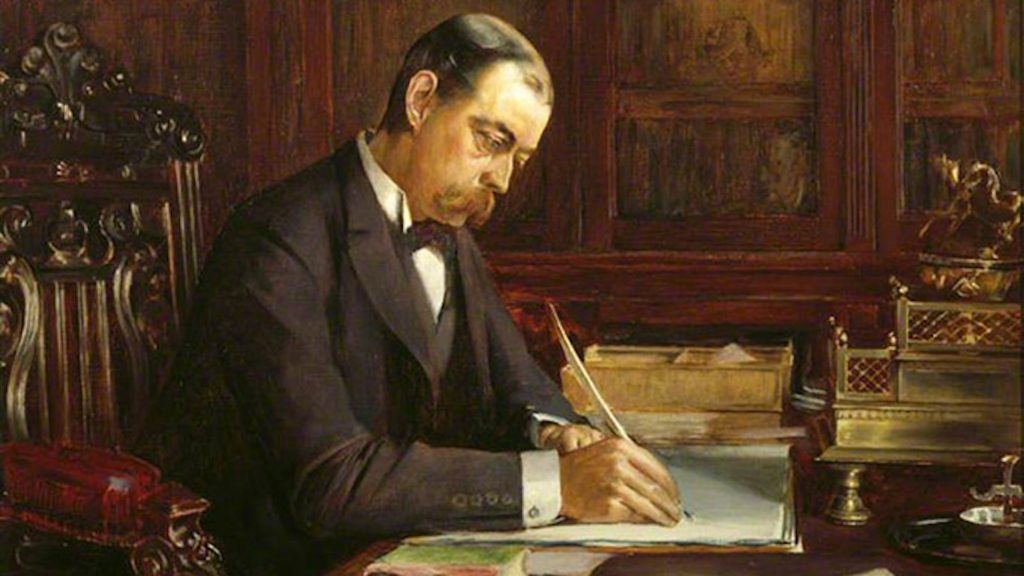

Lord Randolph Churchill

2025 International Churchill Conference

Join Us in Washington, DC, October 9-11

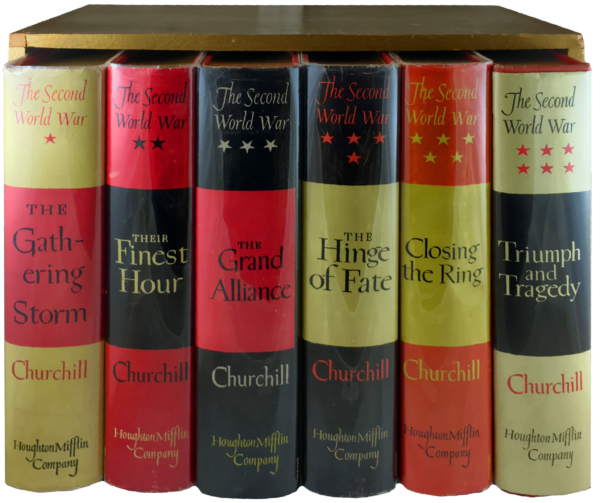

2025 is the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War.

Find Out MoreWriting, Articles & Books

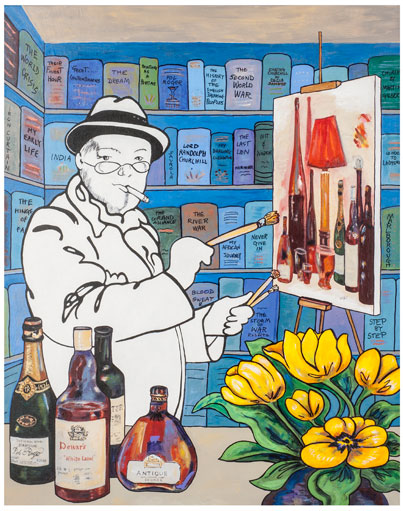

In his lifetime, Churchill published more than 40 books in 60 volumes.

View his writingYoung Churchillians

Working to celebrate the life and achievements of a great leader.

Young ChurchilliansPublications

In his lifetime, Churchill published more than 40 books in 60 volumes.

View PublicationsSubscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.