Churchill in the News

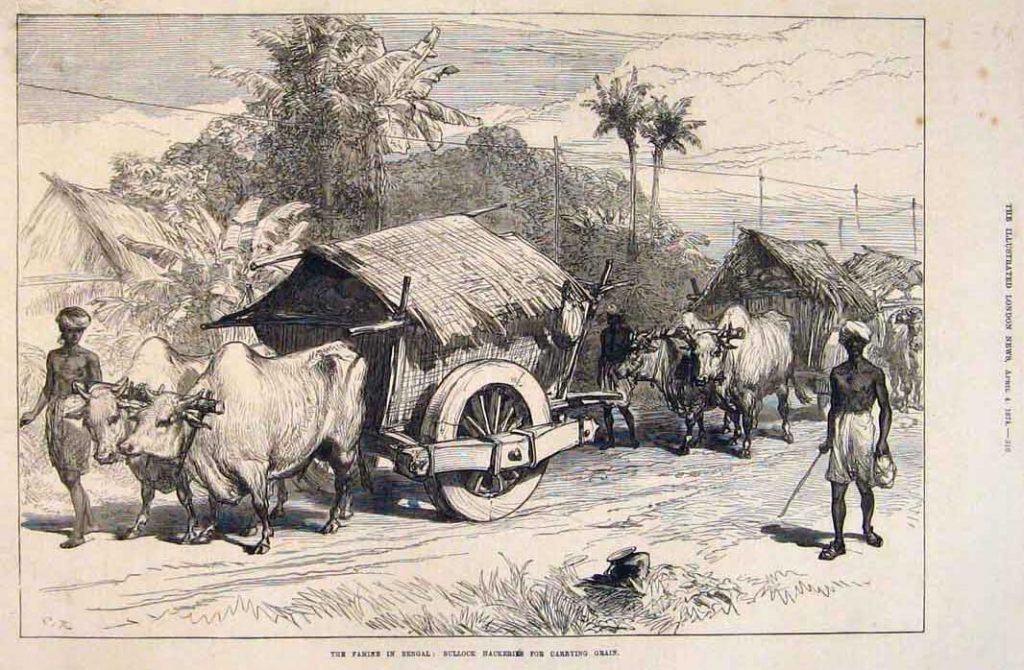

The Bengali Famine

"The Famine in Bengal: Bullock Hackeries for Carrying Grain," from the Illustrated London News, 1874

November 18, 2008

The editors of Finest Hour wish to bestow their 2008 Utter Excess Award on MWC (“Media With Conscience”) News in Vancouver for its November 18th editorial by Gideon Polya, charmingly entitled, “Media Lying Over Churchill’s Crimes”

“Churchill is our hero because of his leadership in World War 2,” Polya writes, “but his immense crimes, notably the WW2 Bengali Holocaust, the 1943-1945 Bengal Famine in which Churchill murdered 6-7 million Indians, have been deleted from history by extraordinary Anglo-American and Zionist Holocaust Denial.”

The article goes on to cite a long list of Churchill “crimes,” including all the old chestnuts (poison-gassing the Iraqis, warmongering before World War I, attacking Gallipoli, bombing German cities, etc.); and some new ones: “Churchill actively sought the entry of Japan into World War 2.” (That one brings to mind Churchill’s occasional observation that he had never heard the opposite of the truth stated with greater precision.) We have dealt with most of them before (over and over)—so let’s consider the flagship accusation.

The Bengali Holocaust

Mr. Polya begins by dismissing all historians who disagree with him as Anglo-American and Zionist propagandists, including official biographer Sir Martin Gilbert—who, since it’s always a good idea to question the accused, we asked for comment. “Churchill was not responsible for the Bengal Famine,” Sir Martin replied. “I have been searching for evidence for years: none has turned up. The 1944 Document volume of the official biography [Hillsdale College Press] will resolve this issue finally.”

We next turned to Arthur Herman’s excellent and balanced Gandhi & Churchill (New York: Bantam, 2008, reviewed in Finest Hour 138: 51-52). There is quite a lot on the Bengal Famine (pp 512 et. seq.), which Herman believes “did more than Gandhi to undermine Indian confidence in the Raj.” Secretary of State for India Leo Amery, Herman writes, “at first took a lofty Malthusian view of the crisis, arguing that India was ‘overpopulated’ and that the best strategy was to do nothing. But by early summer even Amery was concerned and urged the War Cabinet to take drastic action…

“For his part, Churchill proved callously indifferent. Since Gandhi’s fast his mood about India had progressively darkened…..[He was] resolutely opposed to any food shipments. Ships were desperately needed for the landings in Italy…Besides, Churchill felt it would do no good. Famine or no famine, Indians will ‘breed like rabbits.’ Amery prevailed on him to send some relief, albeit only a quarter what was needed.” A quarter of what was needed may also have been all that was possible by ship, but Churchill was also hoping for more aid from India itself.

The Facts

We asked author Herman to elaborate. He writes: “The idea that Churchill was in any way ‘responsible’ or ‘caused’ the Bengal famine is of course absurd. The real cause was the fall of Burma to the Japanese, which cut off India’s main supply of rice imports when domestic sources fell short, which they did in Eastern Bengal after a devastating cyclone in mid-October 1942. It is true that Churchill opposed diverting food supplies and transports from other theaters to India to cover the shortfall: this was wartime. Some of his angry remarks to Amery don’t read very nicely in retrospect. However, anyone who has been through the relevant documents reprinted in The [India] Transfer of Power volumes knows the facts:

“Churchill was concerned about the humanitarian catastrophe taking place there, and he pushed for whatever famine relief efforts India itself could provide; they simply weren’t adequate. Something like three million people died in Bengal and other parts of southern India as a result. We might even say that Churchill indirectly broke the Bengal famine by appointing as Viceroy Field Marshal Wavell, who mobilized the military to transport food and aid to the stricken regions (something that hadn’t occurred to anyone, apparently).”

The salient facts are that despite his initial expressions about Gandhi, Churchill did attempt to alleviate the famine. As William Manchester wrote, Churchill “always had second and third thoughts, and they usually improved as he went along. It was part of his pattern of response to any political issue that while his early reactions were often emotional, and even unworthy of him, they were usually succeeded by reason and generosity.” (The Last Lion, Boston: 1982, I: 843-44).

The Unconsidered Factor: World War II

If the famine had occurred in peacetime, it would have been dealt with effectively and quickly by the Raj, as so often in the past. At worst, Churchill’s failure was not sending more aid—in the midst of fighting a war for survival. And the war, of course, is what Churchill’s slanderers avoid considering.

Martin Gilbert writes about the situation at the time: “The Japanese were on the Indian border with Burma—indeed inside India at Kohima and Imphal in the state of Assam. Gandhi’s Quit India movement, and Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army then fighting alongside the Japanese provided the incentive for a full-scale Japanese invasion. The Royal Air Force and the Army were fully stretched. We know what terrors the Japanese wreaked n non-Japanese natives in Korea, the Philippines, and Malaya.” If the RAF planes supporting India’s defense were pulled off for a famine airlift, far more than three million would have died. The blame for insufficient famine relief lies with those who prevented those planes from being used: the Japanese.

The case against Churchill collapses when we consider the war—just like the oft-repeated complaints that he did nothing for Australia after Japan attacked, or that he didn’t attend Roosevelt’s funeral out of pique or envy. There was a war on. More pressing military matters were at hand which governed his actions and decisions.

Bottom Line

What have we left beside the falsehood of “deliberate, sustained, remorseless starving to death of 6-7 million Indians”? As a wrap to its condemnation, “Media With Conscience” culls out every critical quote it can find by Churchill on Indians. Thirteen years ago at our 1995 conference, one of these was recited by William F. Buckley, Jr.:

“Working his way through disputatious bureaucracy from separatists in New Delhi he exclaimed, to his secretary, ‘I hate Indians.’ I don’t doubt that the famous gleam came to his eyes when he said this, with mischievous glee—an offence, in modern convention, of genocidal magnitude.”

Sure enough, the quotation resurfaces in “Media With Conscience,” described as Buckley predicted: an offense of genocidal magnitude.

This article is a prize-winning example of non-history: the myopic determination to find feet of clay in a man who was human and made mistakes, like everybody else, but who remains admirable, warts and all, mostly because he gave all his papers to an archive where carpers can pore over them.

One of his more balanced critics observed recently that Churchill may have had one foot of clay, but that the other foot was anchored firmly in his innate decency. His biographer once remarked that, as he sorted through the tons of paper in Churchill’s archive, “I never felt that he was going to spring an unpleasant surprise on me. I might find that he was adopting views with which I disagreed. But I always knew that there would be nothing to cause me to think: ‘How shocking, how appalling.’”

Yes, Churchill had a blind spot where Gandhi was concerned, despite the positive things he wrote and said to Indians, from Birla and Gandhi in 1935 to Nehru in 1953, which his critics never bother to quote. And Thomas Malthus may have influenced Amery’s initial view that the famine was caused by overpopulation. But Winston Churchill did not cause or wish for the death of Bengalis. His impulses in situations of human suffering were the opposite of hateful. After World War I, for example, it was Churchill who urged the Cabinet to send boatloads of food to the blockaded Germans—a proposal greeted with derision by colleagues such as Prime Minister Lloyd George, who preferred to “squeeze the German lemon until the pips squeak.” Their policy prevailed—and we all know what it led to twenty years later.

Perhaps the best summation of this particular piece of invective is that lovely line by Jack Nicholson in the charming film As Good As It Gets: “Sell crazy someplace else. We’re all stocked up here.”

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.