Finest Hour 200

Seeing the Balance Turn

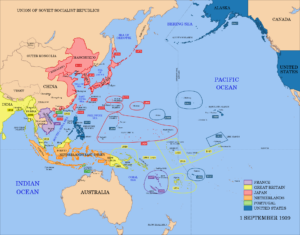

Map of the Battle of the Atlantic

July 16, 2024

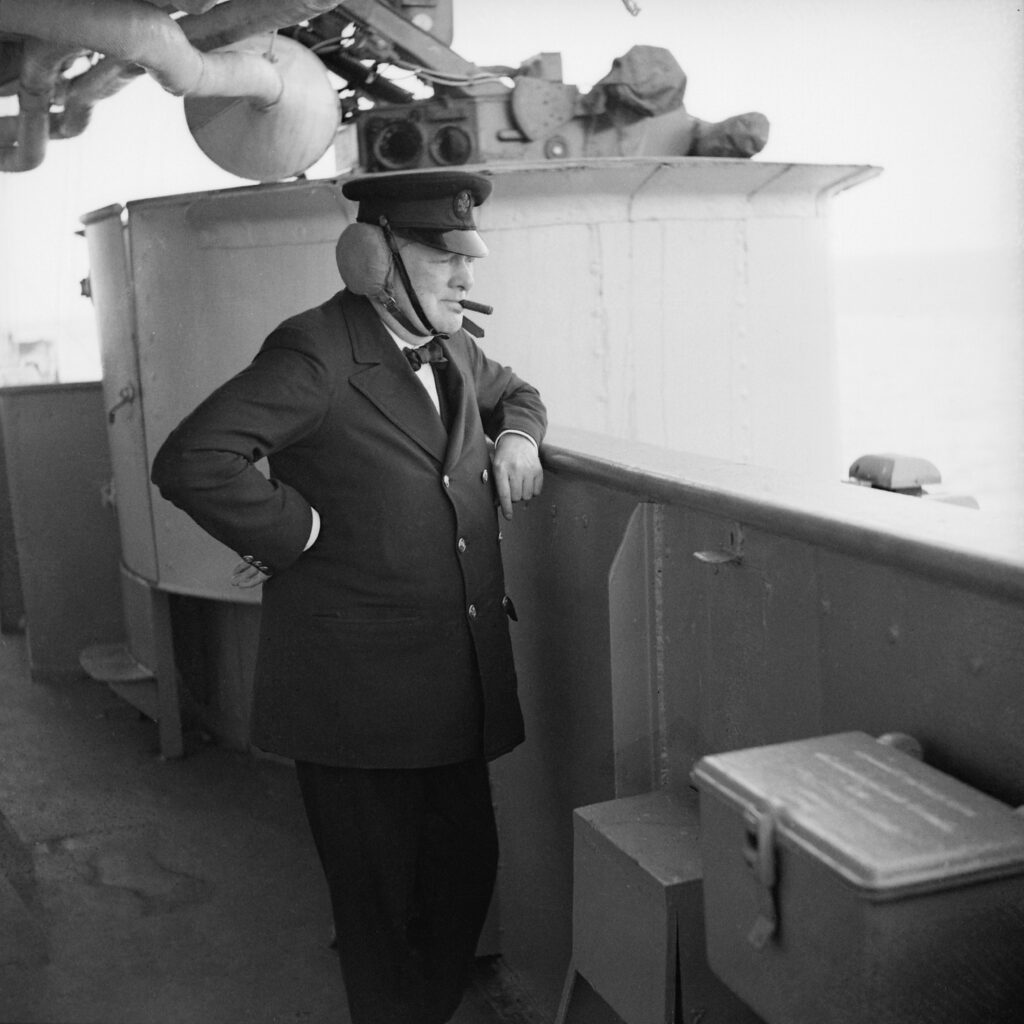

Winston Churchill and the Battle of the Atlantic1

Finest Hour 200, Fourth Quarter 2022

Page 14

By Evan Wilson

Evan Wilson is an associate professor in the Hattendorf Historical Center at the US Naval War College, specializing in the naval history of Britain and other countries from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries. This essay is based on a 2021 article he published in the Journal of Military History.

After the Second World War, Winston Churchill recalled that there was one campaign on which the entire British and indeed Allied effort had depended: “Amid the torrent of violent events one anxiety reigned supreme. Battles might be won or lost, enterprises might succeed or miscarry, territories might be gained or quitted, but dominating all our power to carry on the war, or even keep ourselves alive, lay our mastery of ocean routes and the free approach and entry to our ports.”2 Failure in the Battle of the Atlantic meant failure in the war. It really was as simple as that.

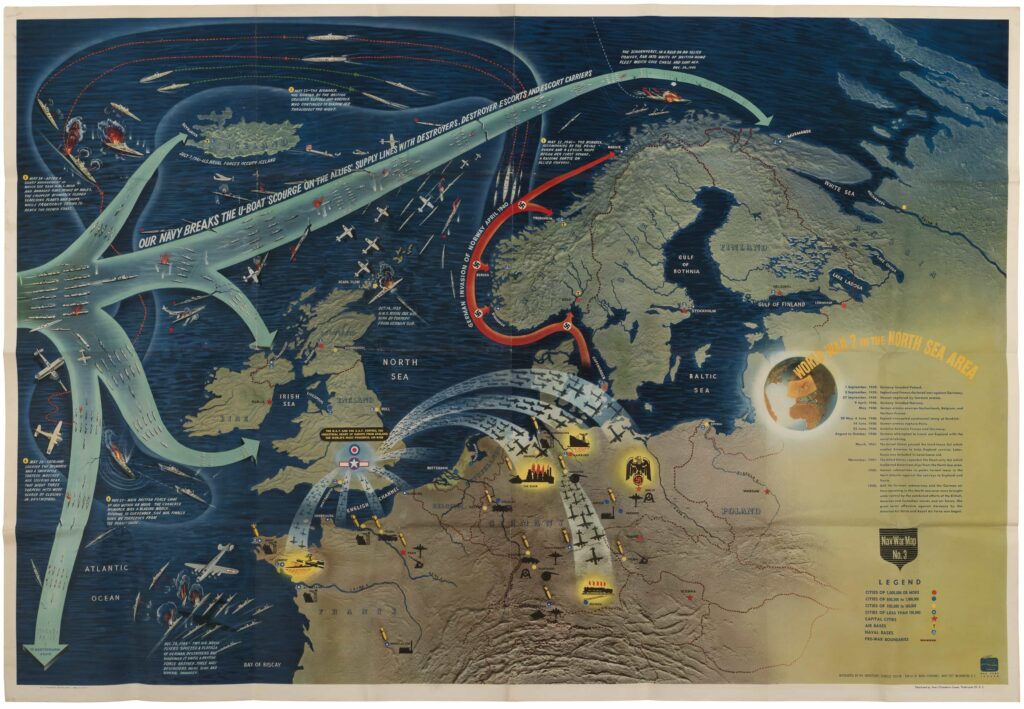

What is not so simple is making sense of the ebbs and flows of the Battle of the Atlantic eighty years later. The battle (really, campaign) began on the first day of the war, when the British and Canadians instituted naval control of shipping, or the convoy system. It lasted until the last week of the war, when American warships sank U-853 off the coast of Rhode Island and an RAF Catalina damaged U-320 off the coast of Norway. In between, thousands of individual battles, many of them now forgotten, were fought across thousands of square miles of ocean. The result is well understood: the Allies defeated the U-boat threat and secured the sea lines of communication between North America and Europe. But when they achieved that goal and how they did it remain questions that animate historians today.

A good starting point for answering those questions is Churchill himself. No person in history has been so well-placed to make sense of them. Not only was he the wartime leader who experienced the victories and defeats at sea in real time, but also after the war he wrote influential and bestselling histories of those events. As he saw it, the Allies won because of the overwhelming tonnage produced by American shipbuilding. It arrived in the theater just in time, in the winter and spring of 1942–43. Those pivotal months saw both the nadir and the zenith of the Allied war against the U-boats. In The Hinge of Fate, he claimed, “The year 1942 was to provide many rude shocks and prove in the Atlantic the toughest of the whole war.”3 But in April 1943, he wrote in Closing the Ring, “we could see the balance turn.”4

2025 International Churchill Conference

Churchill’s interpretation of the events has largely stood the test of time. It is still common to read narratives of the battle that suggest that the Germans were on the brink of victory as 1942 turned to 1943, only to suffer a backbreaking defeat that spring. But more recent scholarship, relying on both decades of historical analysis as well as access to German sources unavailable to Churchill, suggests a different interpretation. In fact, while there are some superficial reasons why the battle seemed to turn in the spring of 1943, a deeper look shows that the Allied position was already very strong. In short, Churchill largely identified the how, but he was too pessimistic about the when.

To understand why this new interpretation matters, we need to begin with the standard narrative of the 1942–43 turning points. What follows relies both on Churchill’s own accounts as leader, as well as his and other historians’ narratives of the Battle of the Atlantic that have been written in the years since.

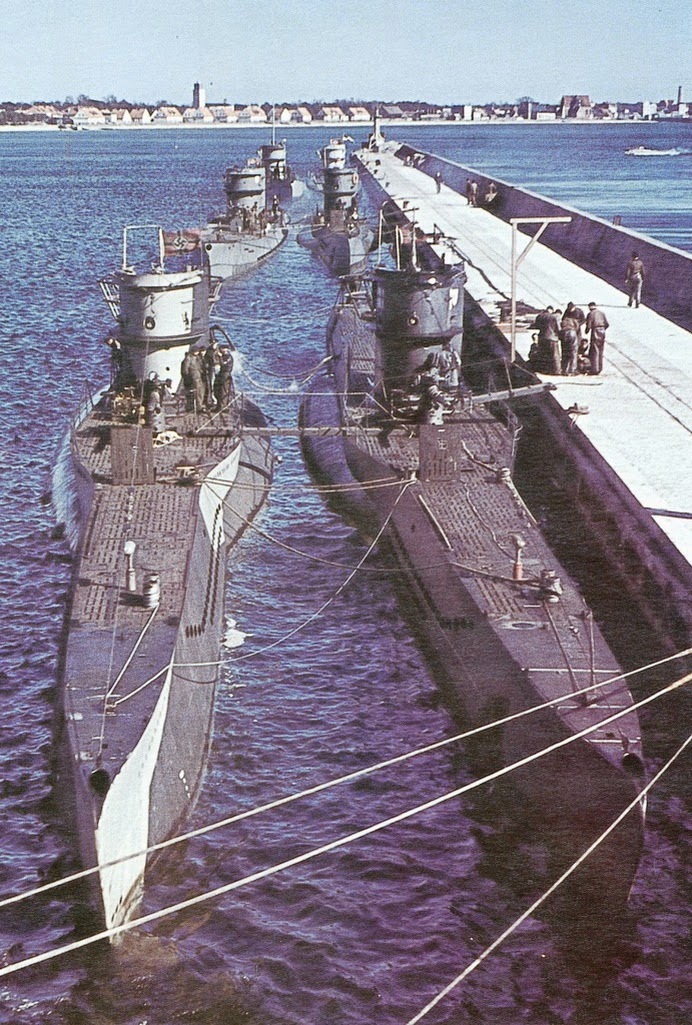

Churchill’s Torments

Churchill wrote fretfully to President Roosevelt on October 31, 1942: “The spectacle of all these splendid ships being built, sent to sea crammed with priceless food and munitions, and being sunk—three or four every day—torments me day and night.”5 What spurred Churchill’s letter to Roosevelt was news of the massive shipping losses the Allies had suffered that month. German U-boats had sunk eighty-nine ships displacing 583,690 tons. Worse news was to come, as in November, the Germans sank 126 ships displacing 802,160 tons. Admiral Karl Dönitz, soon to be head of the German navy, had for the first time seen his U-boats achieve his goal of sinking 800,000 tons per month. He estimated that he could close the Atlantic if that rate was sustained for an extended period. Alarm bells rang on both sides of the Atlantic that winter. If the Germans had made a breakthrough in the convoy war, the entire European theater was in jeopardy.

The next three months provided some relief to the Allies. Bad weather in December, January, and February across the North Atlantic prevented U-boats from spotting targets more than it prevented convoys from getting through. U-boats were naturally poor sailors, and it was difficult to see anything from a conning tower in heavy seas. But once the weather abated in March 1943, the U-boats picked up right where they left off. HX-229 was a fast eastbound convoy that overtook the slow convoy SC-122 in mid-ocean, meaning that on March 16, there were about 100 ships within 150 miles of each other in the North Atlantic. Combined, the two convoys had just fourteen escorts, and they were well away from land-based air cover. From the German perspective, this was as ripe a target as could be hoped for, and Dönitz directed more than three dozen U-boats to attack. They sank eight ships, and the next day, U-338 by itself sank four ships with one torpedo salvo. Across the entire month of March 1943, Allied losses totaled eighty-four ships displacing more than 635,000 tons. Allied leaders worried that the Germans were getting close to sinking enough ships again to threaten the Anglo-American artery.

In fact, they were not. On March 19, Bletchley Park finally broke German signals again, after thirteen months in the dark following the introduction of the fourth rotor on Enigma machines. In late April, the westbound convoy ONS-5 suffered thirteen ships sunk over the course of an epic continuous battle that pitted at least forty-two U-boats against just twelve escorts. But the cost to the U-boats was high—seven were sunk and a further seven were severely damaged. It was a harbinger of casualties to come. In May, convoy SC-130 used Bletchley Park decrypts to route through a gap in Dönitz’s wolfpacks, but Dönitz countered using signals intelligence of his own. In the resulting battle, none of the thirty-eight merchant ships in the convoy was sunk, but three U-boats went down, including one with Dönitz’s son on board. All told, the Germans lost forty-one U-boats in May 1943—an unsustainable casualty rate that forced Dönitz to redeploy them away from the North Atlantic. “We had lost the Battle of the Atlantic,” he later wrote in his memoirs.6 What turned the tide, most historians argue, was the development and deployment of new technologies, combined with increased firepower. Allied escorts now had radar that allowed them to engage U-boats before they reached the convoys, and USS Bogue was deployed as the first escort carrier in March, vastly increasing air cover in mid-ocean.

What Happened?

There is much to recommend the standard narrative. As illustrated by the four famous convoys HX-229, SC-122 (Allied losses), ONS-5 (a draw), and SC-130 (an Allied victory), superior Allied firepower steadily transformed the U-boats from the hunters to the hunted. Yet it is worth taking a step back to ask whether this is really the whole story. There are hints in the retelling of the convoy battles that something might be off. For example, the three months of December 1942 to February 1943, when bad weather hampered the U-boats’ effectiveness, were three months in which Dönitz failed to achieve his tonnage target. Also, while the famous convoys were fighting their way back and forth across the Atlantic, many other convoys reached their destinations unnoticed by the Germans (not to mention some historians).

On the night of March 16, it is true that eight ships and their crews were lost in wave after wave of wolfpack attacks; it is also true that four other convoys were in the Atlantic, bringing vital supplies to Gibraltar and to the Soviet Union. While ONS5 desperately clawed its way back to Halifax, no fewer than eight other convoys totaling 350 ships were at sea, unharried by wolfpacks. In his history, Churchill correctly identified the stakes in the Battle of the Atlantic: if these convoys all suffered the same fate as HX-229 and SC-122, the Allied war effort might collapse. But they did not. Therefore, the careful historian should ask whether the Atlantic was as close to being closed in the winter and spring of 1942–43 as Churchill (and many historians since) have told us. Put another way, were those few months in the North Atlantic really the “hinge of fate”?

To answer this question, it can be helpful to think about what it would have looked like if the Germans had closed the Atlantic. It would not have meant that no Allied ship could have steamed across the Atlantic. It is simply too big an ocean for even hundreds of U-boats to patrol. Rather, German victory would have meant sinking sufficient supplies consistently, over a long enough period, to starve Britain into a negotiated peace. In practice, the Germans probably would have deterred most convoys from sailing by sinking ships at such a high rate that the cost to the Allies in ships, men, and material could not have been borne. It is impossible to be precise about how much tonnage the Germans would have needed to sink to achieve this goal, but for the purposes of this argument, we can take Dönitz’s own estimate from July 1941 of 800,000 tons per month for an extended period as a starting point.

When framed like that, it becomes clear that Germany’s best opportunity to win the Battle of the Atlantic was not in 1943 but instead in the opening years of the war. Following the fall of France in June 1940, Britain was isolated, as readers of this journal know well. To keep from having to fight on the beaches, it was essential to get foodstuffs and war material delivered safely from overseas. Dönitz leapt at the opportunity to operate his U-boats out of bases in northwestern France, which undermined British naval strategy and dramatically shortened the transit times for U-boats to the convoy routes. Meanwhile, the United States was not yet mobilized and hesitant to join the war. A concerted effort to starve Britain out in the months following the fall of France stood a chance of success. Churchill certainly thought so: “The U-boat attack was our worst evil. It would have been wise for the Germans to stake all upon it.”7

Yet the Germans did not stake all upon it, for two reasons. First, the fall of France shocked the world. No informed observer, and more specifically, no leading German naval officer, thought that less than a year into the war, U-boats would be able to bypass the English Channel and North Sea chokepoints to gain direct access to the North Atlantic shipping routes. As a result, the Germans did not prioritize U-boat construction before the war. When the war began, the Germans had fewer submarines than the French. After France fell, U-boat construction had to compete for resources with the Wehrmacht’s preparations for the invasion of the Soviet Union. It was not until July 1941 that Dönitz finally had more operational U-boats than he had had on the first day of the war.

The second reason why the Germans did not stake all upon the U-boats was that they feared the consequences of putting all their eggs in one naval basket. Not only was it not certain that U-boats would be able to locate, attack, and sink sufficient ships to starve the British, but the last time they had tried this strategy, in the First World War, it had accelerated American entry. Everyone remembered the Lusitania. Nothing caused the German Naval War Staff more anxiety than a repeat of those events. They understood that the U-boat was an economic weapon designed for a long war, but that Germany’s best chance of winning the war depended on knocking Britain out quickly. By attacking the shipping lanes that connected Britain to Canada, they increased the chances that they would bring about American entry.

The Germans feared American entry because they recognized that American economic power would tip the scales towards the Allies before a single American serviceman fired a shot. Specifically, in the Atlantic, the United States could build ships faster than the Germans could sink them. In December 1942, the Germans sank 400,000 tons—down from their November peak because of the weather, but nevertheless an ominous achievement. Yet that month, American yards produced more than a million tons of ships. It was the first month in which they reached that milestone, but they surpassed it in nearly every month for the rest of the war. Dönitz’s U-boats could not afford a single month below their target of 800,000 tons, yet it turned out that November 1942 was the only month they reached it. In any case, now that American shipbuilding was mobilized, their target was almost certainly too low.

Few understood this equation better than Winston Churchill. It is ironic that his framing of the spring 1943 turning point in the Battle of the Atlantic has had the unintended consequence of downplaying the importance of getting the Americans into the war. After all, that was his great fixation from the moment he became Prime Minister. He was famously euphoric after Pearl Harbor: “No American will think it wrong of me if I proclaim that to have the United States at our side was to me the greatest joy…. So we had won after all!”8 The reason, as far as the Atlantic was concerned, was simple: “The foundation of all our hopes and schemes was the immense shipbuilding programme of the United States.”9

Diminishing the Danger

It is true that shipbuilding alone was not enough to win the war or even to keep the Atlantic open. It is easy to get distracted by the astonishing accomplishment of American shipbuilding, important as it was. The Battle of the Atlantic was not simply an economic race in which a referee would award victory to the side with the greatest tonnage; it was a shooting war, and U-boats had to be sunk. Convoy battles like HX-229 and SC-122 were not sustainable for the Allies, no matter how many ships were launched. The U-boats had to be defeated to prevent those kinds of convoys from becoming the norm. It was essential to develop the technologies, build the platforms, and train the men to attack U-boats on and below the surface. In that sense, the spring of 1943 really was a turning point because U-boat losses became unsustainable. Dönitz’s own admission of defeat dates from this period for that reason.

When we study the Battle of the Atlantic and its role in the Second World War, we need to be able to hold two seemingly contradictory thoughts in our heads at the same time. The first is that it was highly unlikely that the Germans could ever close the Atlantic. They did not prioritize that strategy before the war, and the fall of France caught them as much off guard as it did the British. The more ships the Germans sank, the closer Britain came to starvation, but also the higher the risk that Germany would bring the United States into the war. The Germans knew this, which is why their approach to the Atlantic was always a little hesitant. The second thought is that even though German victory in the Battle of the Atlantic was unlikely, Allied leaders had to worry disproportionately about it. Defeat in the Atlantic meant defeat in the war. The chances of British defeat were highest from June 1940 through December 1941, and the Anglo-Canadian accomplishment of those eighteen months stands out as the greatest of the campaign.

The convoy battles of the spring of 1943 allow us to reconcile those thoughts. The arrival of millions of tons of American shipping in the winter of 1942–43 lowered the stakes in the Atlantic for the Allies, but it did not eliminate them entirely. Now that the United States was in the war, moreover, there was no reason for the Germans to hesitate. After Dönitz became the head of the navy and prioritized U-boat construction, the great confrontations between wolfpacks and convoys could take center stage. None of the Allied leaders relished the idea of trying to invade Hitler’s Europe while the sea lines of communication were under such threat. Even if a German victory was highly unlikely, the U-boat menace had to be eliminated. Despite a scare in March 1943, the convoys and their escorts won. While the Atlantic campaign continued right up to the last week of the war, Allied escorts, escort carriers, and air power broke the back of the U-boat force in May and June 1943. That victory substantially diminished the danger to the sea lines of communication, and in that sense proved to be fundamental to Allied victory in Europe. Therefore, we should not be surprised to read from those who were there that the convoy battles of early 1943 really were the hinge of fate.

Endnotes

1. I am grateful to Mahlon Sorensen for his assistance in preparing this article. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the US Government, the US Navy, or the US Naval War College.

2. Winston Churchill, The Second World War, vol. III, The Grand Alliance (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1950), p. 98.

3. Winston Churchill, The Second World War, vol. IV, The Hinge of Fate (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1950), pp. 95–96.

4. Winston Churchill, The Second World War, vol. V, Closing the Ring (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1951), p. 8.

5. Craig L. Symonds, World War II at Sea: A Global History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 373.

6. Karl Dönitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days, translated by Jak P. Mallmann Showell (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1990), p. 341.

7. Churchill, Hinge of Fate, p. 110.

8. Churchill, The Grand Alliance, p. 539.

9. Churchill, Closing the Ring, p. 4.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.