Finest Hour 200

“What Was MY Monty Doing Now?”

Battle of El Alamein

July 16, 2024

Churchill, Montgomery, and the Political Battle of El Alamein

Finest Hour 200, Fourth Quarter 2022

Page 20

By Nigel Hamilton

Nigel Hamilton is author of Monty: The Making of a General (1981) from which this article has been adapted and expanded.

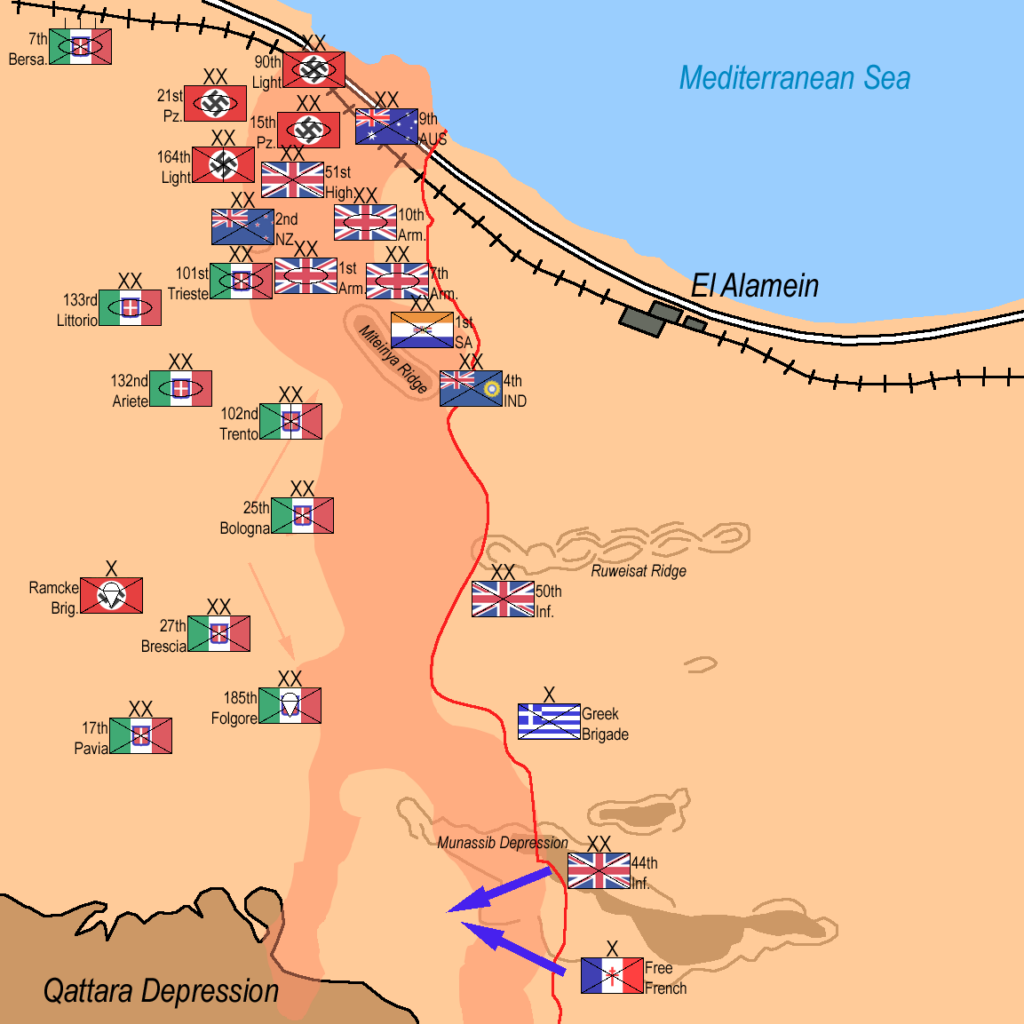

In August 1942 Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) Alan Brooke, inspecting the Middle East, decided to replace General Claude Auchinleck with General Harold Alexander as Commande-rin-Chief of the theatre. Since Auchinleck had doubled as commander of the British 8th Army at Alamein, west of Cairo, a new army commander was also required. Despite warnings by his military advisers, Churchill chose General “Strafer” Gott, a brave but exhausted Corps commander he had met when visiting the defeated army. Gott was killed when flying back to Cairo for a rest and bath, however. A summons was therefore dispatched by Churchill to London to send out General Bernard Montgomery, forever remembered as “Monty.”

After halting Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s final Panzer offensive to seize Cairo that month, Montgomery carefully prepared an offensive to be mounted against Germany’s Afrika Korps (DAK). If successful the counter-attack would push the German-Italian Panzer Army—led by its already legendary commander, “the Desert Fox”—out of Egypt and turn the tide against the Axis powers in North Africa.

The battle began on the evening of 23 October 1942, but— as typically happens in war—not all went according to plan.

2025 International Churchill Conference

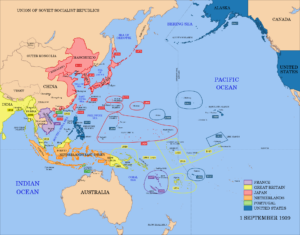

Lieutenant-General Herbert Lumsden, commanding the 10th Armoured Corps, was supposed to use his tanks to lead a Corps de Chasse in conjunction with the main attack, which would be carried out by 30 Corps, led by Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese, while it was hoped that 13 Corps, led by Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks, would distract Rommel further south. The initial phase of the battle was given the inappropriate name—given the massed artillery barrage— “Lightfoot.”

Though the initial “breakin” cleared a number of lanes through the half-million mines Rommel had sown at Alamein, the British assault across the Miteiriya Ridge, the German defensive line, essentially failed. Despite having previously agreed with Monty’s battle plan, Lumsden now fiercely protested to the army commander in the early hours of 25 October that the pathway for British armour had not been sufficiently cleared of mines and barbed wire, or from anti-tank fire, making it suicidal to press the attack further. Montgomery felt Lumsden had suffered a failure of nerve; nevertheless he revised his plan by reducing his attack from using six armoured regiments to one, and placing the remainder in reserve.

Alarm Bells

The lone remaining armoured regiment engaged in the battle, the Staffordshire Yeomanry, suffered brutal losses, but it was the withdrawal of the majority of 8th Army’s armour that did more than anything else during the Battle of El Alamein to cause consternation in Cairo and London.

There had been no mention of such an eventuality in the “Lightfoot” plan, which assumed that British armour would remain “out” in the minefields until it had destroyed the Axis armour. Yet General Montgomery started to withdraw the entire 10th Corps on 28 October.

Quite who began to spread the rumour that all was not well with 8th Army is unknown—but from General Sir Alan Brooke’s diary it is clear that the culprit in London was Anthony Eden, Churchill’s Foreign Secretary. On the night of 28 October, Eden went round to 10 Downing Street “to have a drink with him [Churchill] and had shaken his confidence in Montgomery and Alexander and had given him the impression that the Middle East offensive was petering out!!” Brooke learned the following morning: “Before I got up this morning I was presented with a telegram which PM wanted to send Alexander. Not a pleasant one!” Brooke managed to scotch the telegram, but at Eden’s insistence the British Minister of State in Cairo, Richard Casey, was cabled to go up to the Alamein front and report back.

When Brooke heard about it a little later, he was furious. During a Chiefs-of-Staff meeting, “while we were having final interviews with Eisenhower, I was sent for by [the] PM,” Brooke noted, “and had to tell him fairly plainly what I thought of Anthony Eden and [his] ability to judge a tactical situation at this distance.” In his Notes on My Life, Brooke later elaborated: “What, he [Churchill] asked, was MY Monty doing now, allowing the battle to peter out?… He had done nothing now for the last three days, and now he was withdrawing troops from the front. Why had he told us he would be through in seven days if all he intended to do was to fight a half-hearted battle. Had we not got a single general who could even win a single battle, etc. etc. When he stopped to regain his breath I asked him what had suddenly influenced him to arrive at these conclusions.” On hearing that the culprit was Eden, Brooke lost his temper. “The strain of battle had its effect on me,” Brooke acknowledged in retrospect, “the anxiety was growing more intense every day and my temper was on the edge.”

Churchill retorted that he was entitled to consult whomsoever he pleased. “He continued by saying that he was dissatisfied with the course of the battle and would hold a Chiefs-of-Staff meeting under his chairmanship at 12:30 to be attended by some of his colleagues.” In front of South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts and the Chiefs of Staff, Churchill—who was not only Prime Minister, but had appointed himself Minister of Defence—produced the infamous telegram again, criticizing Alexander and Montgomery. All Churchill’s fears about the depth of the Axis minefields at Alamein (which he had seen on his visit) and the peril of delaying the British offensive beyond September seemed to have been borne out. Once again Churchill’s own political position was at stake, not only in terms of possible Parliamentary rejection of his premiership, but in relation to the Prime Ministers of the Commonwealth, whose troops were so deeply committed in the Alamein battle. On top of the casualties suffered by New Zealand, Australian, South African, Canadian, and Indian forces in Greece, North Africa, the Far East, and at Dieppe, the heavy losses sustained already at Alamein promised—if Montgomery failed to achieve decisive victory—to cost Churchill his premiership.

Brooke, however, was in the same critical situation, and his diary records quite unequivocally how much he felt his position as CIGS hung on the successful outcome of the battle of Alamein: “if we had failed again I should have little else to suggest beyond my relief by someone with fresh and new ideas!” he confessed at the end of the battle. Yet it was precisely the critical importance of the battle to his military strategy and to his personal position that now made Brooke stand up to Churchill in a way that he had failed to do in August, when Churchill appointed the exhausted Gott to command the 8th Army. Brooke had not heard from Montgomery directly, but he felt sure the general was withdrawing formations in order to create new striking reserves. “I then went on to say that I was satisfied with the course of the battle up to the present and that everything I saw convinced me that Monty was preparing for his next blow.” Churchill climbed down, and dissembled to Smuts, pretending he had not previously discussed the matter with Brooke, and that he agreed with the CIGS entirely. The telegram was scrapped.

Anxieties

Brooke, however, was far from convinced by his own military logic. “On returning to my office,” he later recalled, “I paced up and down, suffering from a desperate feeling of loneliness. I had during the morning’s discussion tried to maintain an exterior of complete confidence. It had worked: confidence had been restored. I had told them what I thought Monty must be doing, and I knew him well, but there was just that possibility that I was wrong, and that Monty was beat.”

Were Brooke’s fears groundless? In a letter to Brooke on 1 November, as the battle still raged, Montgomery insisted he had “managed to keep the initiative throughout and so far Rommel has had to dance entirely to my tune; his counter-attack and thrusts have been handled without any difficulty up to date.” This was neither true nor helpful; the battle, after all, was not meant to be a grinding one of defense; it was planned to be an offensive battle that would destroy Rommel’s army, at the end of extended Axis supply lines going all the way back to Tunis. In terms of offensive battle, Monty blamed Lumsden, deriding the armoured general’s performance as Commander of the British Corps de Chasse, one which did not look ready to chase anyone.

To his staff, as opposed to his letters to Brooke, however, Monty showed nothing but confidence. He retired to his trailer bed at the same time each night, beneath a portrait of his opponent, Rommel, and exuded optimism by day. Yet from his diary and his bitter disappointment in Lumsden and the contribution of British armour, it is evident he was far from satisfied with the way the battle had gone since the break-in on the first night. In withdrawing the tanks of 10 Corps—which suffered grievously from German 88-mm anti-tank weapons possessed with laser-like accuracy unmatched by British weapons—he was in reality bowing to the inevitable. From the very beginning Lumsden and the Armoured Commanders had been understandably unwilling to fight “up front” in closely contested, heavily-mined desert, with no cover. In withdrawing his armour, Montgomery was thus abandoning the policy he had laid down for the battle—that of the armoured “shield,” which would protect the infantry’s “crumbling” attacks and draw upon itself German armoured counter-attacks. Instead, faute de mieux, he was reverting to an almost First World War infantry-style battle—one that would entail yet more heavy casualties.

That Montgomery considered his armour to be more of a liability than a help in winning the battle—beyond the fear it had raised in Rommel’s mind—is demonstrated by the fact that, within hours of Rommel’s having thrown in the combined weight of his Afrika Korps, Monty was planning to send his entire armoured Corps to the rear, and allow Leese to undertake the protection of his own bridgehead with artillery, not tanks. The armour had indeed been instrumental in forcing Rommel into costly armoured counterattacks—but in such a limited, still heavily mined area that, as Monty recorded in his diary, he would “never get the armoured divisions out that way.”

For the moment, then, Montgomery decided to fight the battle of Alamein as an infantry battle, keeping his armour entirely in reserve. On the night of 28 October, the Australians delivered their next “crumbling” attack northwards from the bridgehead. Through this Australian “thumb,” as it was called at 8th Army headquarters, Monty hoped to pass the combined armour-infantry reserve he was assembling under the intrepid New Zealand commander, Lieutenant-General Bernard Freyberg; since the British army had failed to push out the intended armoured shield ahead of the infantry, however, it was now increasingly difficult for the heroic Australians to make headway in such a narrow area.

Rommel’s View

For Rommel the battle had already become, quite literally, a matter of life or death—“rivers of blood” sacrificed for a line in the sand. He had written to his wife on the morning of 28 October—at the same time that Churchill was ranting against his general in the field—“Whether I would survive a defeat lies in God’s hands…After I am gone, you must bear the mourning proudly.” The capture of a British map showing Montgomery’s intended drive north-west from the Australian salient confirmed Rommel’s feeling that the critical moment of the battle had arrived—though he mistakenly thought Montgomery was about to launch an all-out armoured break-through. Accordingly, “the whole of Afrika Korps had to be put into line,” he recorded in his Memoirs, and he “again informed all commanders that this was a battle for life or death and that every officer and man had to give of his best.”

That evening Rommel’s day report to OKW (the German High Command) for 28 October was decrypted, describing the situation as “grave in the extreme.” Churchill summoned Brooke at 11:30 pm—an hour and a half after the Australian attack began—and showed him Rommel’s decrypted message, obtained from Ultra: “He had a specially good intercept he wanted me to see and was specially nice,” Brooke recorded in his diary. Referring to the Middle East, he said, “Would you not like to have accepted the offer of Command I made to you and be out there now?”

After Churchill’s tirade that morning, this volte-face astonished Brooke—especially when Churchill went on to say how grateful he was that Brooke had elected to stay and serve the Prime Minister in London.

The courageous resistance put up by the Germans in the north blunted the Australian attack, which reached the coastal railway line, but not the sea. For Rommel, however, it was quite obviously but the tip of the iceberg. “No one can conceive the extent of our anxiety during this period,” he wrote afterwards.

The RAF and the Royal Navy had kept up their pressure on Rommel’s petrol supply routes— as at Montgomery’s earlier, defensive battle at Alam Halfa— and by the morning of 29 October Rommel was clear that he must prepare for withdrawal to Fuka, on the coast, further back, “before the battle reached its climax.” To his wife he confessed in his daily letter: “I haven’t much hope left.” He was certain that this was the decisive battle of the war. At 2:45 pm Rommel’s aide noted in his diary: “C-in-C enlarges over lunch on his plan to prepare a line for the army to fall back on at Fuka when the time comes, now that the northern part of the Alamein line is no longer in our hands.”

Monty’s View

For Montgomery the responsibility for ensuring actual victory hung heavily. The battle had raged for eight long nights and seven days. From the tally kept of enemy tanks and guns destroyed, as well as mounting numbers of prisoners and his Ultra decrypts, he knew how desperate the situation must look to Rommel, however. At 11:15 pm the previous night, 28 October, his Intelligence staff had identified 90th Light Division, formerly in the southern sector, fighting in the extreme north, to the west of the Australians—an indication that Rommel was throwing everything he had into that sector in order to prevent 8th Army breaking out. But the heavy casualties sustained by the Australians and the damage done to their support tanks on the minefields forced Monty to postpone their follow-up attack: “The new front is being re-organized and the attack will be resumed tomorrow night, i.e. Friday, 30 October, when I hope the Australians will reach the sea and clean up the whole area.”

Concerned over the rising casualties, knowing Rommel was near to cracking and having his own version of the Afrika Korps in reserve, still, Montgomery was in no hurry. For the first time in the battle, however, he was now made unequivocally aware of Allied pressure being brought to bear on Churchill in London, especially the American military. At 11:50 am on 29 October he was informed that Churchill’s son-in-law, Duncan Sandys, would visit him the next day; meanwhile, Alexander himself suddenly appeared with Richard Casey, bearing Churchill’s revised telegram. In this the Prime Minister pointed to the imminent American and British landings in North-West Africa (Operation TORCH) and painted a rosy (though illusory) picture of the prospects—namely that the French would assist the Allies in Tunisia and perhaps rise up in Vichy France. “Events may therefore move more quickly, perhaps considerably more quickly, than had been planned,” Churchill signaled, urging that everything now be done to expedite a victory by 8th Army to help TORCH.

Montgomery’s chief of staff, Major-General “Freddie” de Guingand, recalled the new urgency. “There had been a signal or two which suggested that some people were a bit worried that things had not gone faster.” De Guingand coyly remembered: “Montgomery’s reply to such suggestions was that he had always predicted a ten-day ‘dog-fight’ and he was perfectly confident that he would win the battle. I was taken aside by Casey, who asked me whether I was quite happy about the way things were going.”

In fact Casey was so alarmed by the apparent stalemate and the withdrawal of the entire Corps de Chasse that he showed de Guingand a draft signal to London preparing Churchill for a possible reverse. Edgar Williams, Montgomery’s Intelligence chief, remembered the moment quite clearly and recalled that de Guingand suddenly had “an incredible burst of temper, saying: ‘For God’s sake don’t [send it]! If you do, I’ll see you’re drummed out of political life,’” a threat which greatly amused Williams at the time, since de Guingand clearly had “no appreciation that he [Casey] wasn’t in political life anyway!”

In his Memoirs Montgomery claimed to have been too busy to bother about what signal Casey eventually sent. Yet the evidence of his diary confirms that he certainly took seriously the pressure from Casey and Churchill. Churchill’s telegram stated that TORCH was going ahead on the date planned—ten days away—on “8 November,” as Monty recorded in his diary. “It is becoming essential to break through somewhere, and to bring the enemy armour to battle, and to get armoured cars astride the enemy supply routes. We must make a great effort to defeat the enemy, and break up his Army, so as to help TORCH. I have therefore decided to modify my plan,” he concluded: and set down his new intention.

Rather than driving the New Zealanders in a self-replenishing combined armour-infantry offensive through the Australian “thumb” and along the coast to Sidi Rahman, Montgomery would allow the Australians to continue their assault towards the sea in the far north; instead of exploiting it, however, he would then put all his reserve forces into an infantry and armoured attack westwards from the Kidney Ridge area. This “hole” would be “blown” by Freyberg, and would be some three miles deep; through it Monty would then pass his entire armoured Corps and two armoured car regiments:

The Armd Car Regts will be launched right into open country to operate for four days against the enemy supply routes. The two Armoured Divisions will engage and destroy the DAK. This, in effect, is a hard blow with my right, followed the next night with a knock-out blow with my left. The blow on night 31 Oct/1 Nov will be supported by some 350 guns firing about 400 rounds a gun. I have given the name SUPERCHARGE to the operation.

From being held back in reserve until Leese had gradually smashed an infantry path through the Axis forces along the coast, Lumsden’s 10 Corps was being asked once again to take part in an offensive capacity—“a knockout blow.” Whether the armour would cooperate any better than it had in the battle so far remained, however, to be seen.

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.