Finest Hour 200

Churchill and the Hinge of Fate:

The Western Pacific, 1939

July 16, 2024

Confronting the Onslaught of Japan

Finest Hour 200, Fourth Quarter 2022

Page 08

By John H. Maurer

John H. Maurer is Alfred Thayer Mahan Professor of Sea Power and Grand Strategy at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island.

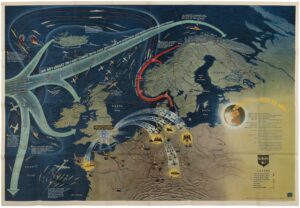

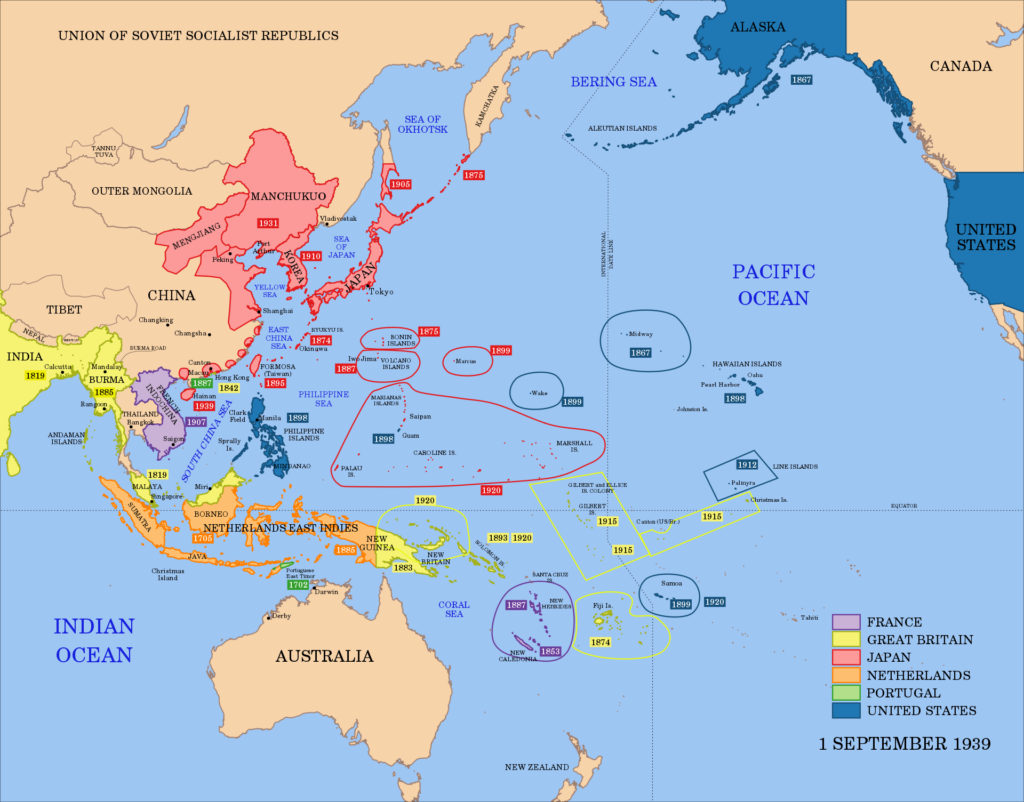

On the eve of the Second World War, the celebrity globetrotting American journalist John Gunther could write, “Great Britain, as everyone knows, is the greatest Asiatic power.”1 Confirmation of Gunther’s claim about Britain’s position in Asia could readily be grasped just by looking at a map of the world, showing British imperial possessions colored in red. The British Empire controlled a vast expanse of territory in Asia, sweeping in a great arc from New Zealand and Australia in the South Pacific to Southeast Asia and South China, and on to India and the Middle East. A quarter of the world’s population, with much of it concentrated in South Asia, lived within Britain’s empire. The empire, too, was rich in the resources that it possessed. A superpower, the leading state of the international system, Britain possessed economic interests and upheld security commitments stretching around the globe.

The Rising Sun

When the gathering storm of the Second World War broke, dangerous great-power challengers aspired to expand their own empires at Britain’s expense. In Asia, the militant nationalist extremists leading Japan imagined their country engaged in a Darwinian struggle to assert their imperial ambitions, and these dreams of empire put their country on a collision course with Britain. To Japan’s rulers, the decline and fall of the British empire in Asia seemed close at hand. One Japanese commentator on world politics and naval strategy argued that “the relative positions of Japan and Britain are incompatible. The teaching of history is that war is inevitable, unless, indeed, England gives way.” He boasted that for Britain to “fight Japan is to court destruction. England had better swallow her pride and make way. That is the wisest thing she can do to protect herself.”2 His message was strident and clear: Japan was the rising great power in the struggle for mastery in Asia, while Britain was on the way out.

The outbreak of war in Europe presented Japan with a golden opportunity to expel British power from Asia. The war against Hitler’s Germany was a struggle for survival. Britain’s armed forces were engaged in desperate fighting to defend the home islands from air attack and deter invasion, to keep open critical sea lanes, to stop Rommel’s German-Italian army from advancing in North Africa, and to provide supplies and weapons that the Soviet Union needed to stay in the struggle. The rulers of Germany and Japan collaborated to advance their international ambitions by negotiating first the Anti-Comintern Pact and, later, the Tripartite Pact. The leaders of Germany and Japan agreed to support each other in “the establishment of a new order” in Europe and Asia. A worst-case scenario was unfolding in which Britain faced being at war with two powerful and aggressive adversaries at opposite ends of the globe.

2025 International Churchill Conference

Winston Churchill had foreseen and warned against this danger of Britain having to fight at the same time wars against major adversaries in Europe and Asia. He had predicted that “should Germany at any time make war in Europe, we may be sure that Japan will immediately light a second conflagration in the Far East.”3 From such a dire strategic predicament, Churchill saw salvation for Britain by aligning with the United States to stop and roll back Japanese aggression in the Pacific. The Japanese strike on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines, along with Hitler’s declaration of war, did bring the entry of the United States into the global struggle. Churchill would later record the relief that he felt at the news of Japan’s attack on the United States. “No American will think it wrong of me if I proclaim that to have the United States at our side was to me the greatest joy,” he wrote. “I knew the United States was in the war up to the neck and in to the death. So we had won after all!” With the United States in the war, Churchill “went to bed and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.”4

Japan’s victories on sea and on land at the onset of fighting in the Pacific, however, seemed to belie Churchill’s belief in the ultimate victory of the Grand Alliance. Britain and the United States suffered one major defeat after another at the hands of Japan. The Japanese surprise attack crippled the American battleline at Pearl Harbor. Just several days later, on 10 December 1941, Japanese land-based naval aircraft, operating out of bases in French Indochina, modern-day Vietnam, struck and sank the British battleship Prince of Wales and battle cruiser Repulse—so-called Force Z—off the coast of Malaya. In sending Force Z to Singapore, Churchill had hoped that it would deter Japanese aggression as well as form the vanguard for a buildup of British naval power in Asia. Called the “decisive deterrent” by Churchill, the forward-deployed capital ships of Force Z failed to achieve their strategic purpose of deterrence and instead became tempting targets to Japanese naval pilots. Churchill would later write that upon hearing the news of Force Z’s destruction, “In all the war I never received a more direct shock.”5

More defeats at sea soon followed. Four months after the destruction of Force Z, the cruisers Cornwall and Dorsetshire quickly sank when deluged with bombs delivered by aircraft from Japanese carriers raiding into the Indian Ocean. The battle fleet assembled by Britain in the Indian Ocean stood no chance in a standup fight with the Japanese carrier force. To avoid annihilation, the British fleet steamed out of harm’s way, retreating all the way across the Indian Ocean to the east coast of Africa to escape Japan’s carrier air power. By pioneering a transformation in the use of air power in naval warfare, the Japanese navy leaped ahead of adversaries, gaining a first-strike strategic advantage that it used to devastating effect. Britain’s Royal Navy had lost command of the sea.

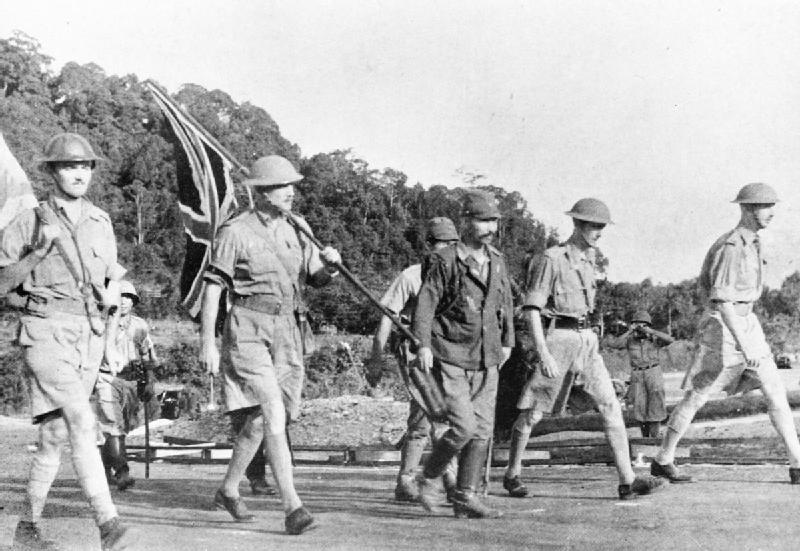

Bereft of an effective naval defense, Malaya and Singapore were open to a Japanese seaborne invasion and their loss was inevitable. Japanese ground forces, landed on the first day of the war, quickly advanced down the Malay peninsula. Singapore fell after a campaign of little more than two months. The rapid defeat of the British forces in Malaya and mass surrender at Singapore staggered Churchill. The British defenders on the ground outnumbered the attacking Japanese invaders, and Churchill expected and urged them to offer a determined and prolonged resistance. As the Japanese launched their final assault to seize Singapore, Churchill sent stern, fight “to the bitter end” orders to British commanders in Asia. “There must at this stage be no thought of saving the troops or sparing the population,” Churchill ordered, “Commanders and British officers must die with their troops. The honour of the British Empire and of the British Army is at stake.” Churchill exhorted his commanders to have the forces under their command fight as stubbornly as the Russian soldiers on the Eastern Front and as the Americans were doing in the Philippines.6 No amount of exhortation, however stirring, could change the outcome. General Arthur Percival surrendered his forces unconditionally on 15 February 1942. The British surrender did not spare Singapore’s population from an orgy of violent terror unleashed by the Japanese conquerors drunk with victory, nor did it prevent the cruel treatment meted out on prisoners of war during their years of captivity.

What Happened?

Could Britain have avoided these defeats? Given Churchill’s strategic priorities in the world war, Britain was practically bound to suffer opening defeats once Japan’s rulers decided to attack. While shortchanging British defenses in Asia, Churchill’s priorities nonetheless made sound strategic sense: (1) defense of the homeland from air assault and potential invasion; (2) keeping open the vital sea lanes of the North Atlantic; (3) sending whatever Britain could spare in supplies and weapons to the Soviet Union; (4) offensive operations against the German-Italian army in North Africa and to secure the Middle East; and (5) finally, a buildup of forces to deter Japan from attacking. Churchill’s strategic priorities ranked deploying forces and supplies to fighting fronts. He explained these strategic priorities to the House of Commons. Confident that if Japan attacked, then the United States would come into the war, Churchill wanted to use Britain’s “limited resources on the actual fighting fronts.” He believed that “if Japan ran amok in the Pacific, we should not fight alone”7

Only by changing these strategic priorities could Britain have hoped to find additional forces to mount a more effective defense against Japan. For example, Britain might have adopted a defensive stance in the Middle East and then sent more ground and air forces to Asia. Britain could also have diverted to Asia aircraft and tanks sent to the Soviet Union. British weapons and supplies delivered to the Soviet Union during 1941 would have helped bolster defenses against the opening Japanese offensive drives. For example, British Hurricane fighter aircraft, if shipped to Singapore rather than the Soviet Union, would have helped to prevent Japan from gaining air superiority in Southeast Asia.

These strategic tradeoffs, however, would have entailed running greater risk of defeat in the Middle East and on the Eastern Front. In both theaters, any weakening of the forces arrayed against the German attackers could well have resulted in military disaster. The Soviet Red Army came perilously close to defeat in the Battle of Moscow and around Leningrad. In North Africa, the German-Italian army inflicted major defeats on the British armed forces, which could have lost Egypt. Staving off disastrous defeats on the Eastern Front or in the Middle East held a higher strategic priority in the period leading up to Japan’s attack. In Russia and Egypt, the Germans came frighteningly close to breaking down the Soviet and British defenses.

A shift in strategic priorities to defend more effectively against Japan would have required that Britain deploy a strong air force and competitive fleet to Southeast Asia, as well as ground forces. Such a massive British buildup of combat forces to conduct sustained operations in Asia would also have entailed a huge logistical effort, with supply chains stretching over great distances, which appeared beyond the available shipping resources. To blunt the Japanese opening offensive, Britain would have had to draw down its air strength in the home islands to acquire the needed forces. If Britain could not gain air superiority, then Japan would have the advantage in the fighting. Beating back Japan’s opening offensive drive, too, would require command of the sea. Japan’s force of six large aircraft carriers, however, was markedly superior to any fleet that Britain could deploy to the Pacific. If the two navies had fought a major fleet battle in the South China Sea or the Indian Ocean, the Royal Navy would most likely have suffered a crushing defeat. Churchill was honest with the House of Commons that, with the Japanese victories at Pearl Harbor and over Force Z, “naval superiority in the Pacific and in the Malaysian Archipelago has passed from the hands of the two leading naval Powers into the hands of Japan.”8 Britain’s loss of air superiority and command of the sea sealed the fate of Singapore.

What Next?

An ugly strategic reality confronted Churchill in late 1941: regaining naval superiority over Japan and commanding the seas of Asia was beyond Britain’s strength while the war against Nazi Germany raged in Europe. Already before the First World War, when serving as First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill had imagined a dreadful future scenario where the British fleet could no longer defend the empire in Asia. “If the power of Great Britain were shattered on the sea,” he warned, “the only course for the five millions of white men in the Pacific would be to seek the protection of the United States.”9 Faced by the looming danger of war with Japan, Churchill reposed his confidence in the American battle fleet to deter Japanese offensive action against the British empire. He believed “that over the whole of the Pacific scene brooded the great power of the United States Fleet, concentrated at Hawaii. It seemed very unlikely that Japan would attempt the distant invasion of the Malay Peninsula, the assault upon Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies, while leaving behind them in their rear this great American fleet.”10

But Churchill’s confidence in the striking power of the American fleet was misplaced. The American battle fleet at Pearl Harbor lacked the capability to execute war plans for an early offensive even before the Japanese attack. The strike at Pearl Harbor, of course, shattered whatever deterrent effect the American battle fleet might have posed to Japanese offensive action in Southeast Asia. Allegations that Churchill possessed foreknowledge of the Pearl Harbor attack and withheld this information from Roosevelt, as conspiracy theories maintain, thus make no sense because he looked to the American fleet to frustrate a Japanese offensive against the British empire. By striking at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese upset Churchill’s strategic calculations and exposed British weakness in Asia.

The appalling defeats suffered by Britain called into question Churchill’s war leadership. Calls came for Churchill to turn over the strategic direction of the war to other (more competent) hands. The defeats in Asia and North Africa prompted two major debates in the House of Commons in which critics assailed Churchill’s decisions. In The Hinge of Fate, Churchill provides a narrative account of the debates, which stand comparison with the speeches recorded by Thucydides in his famous history of ancient Athens, where the Athenian people held their leaders to account for their decisions in war. Churchill’s youngest daughter Mary recorded in her wartime diary the anxiety that she and her parents felt during the debate in the House of Commons when a vote of censure was moved against the government: “As I sat in the gallery & listened to all those carping voices—I watched the unhappy set of Papa’s shoulders—& my heart went out to him in his anxiety & grief.” Sitting through the debate, she felt “terribly tensed up. Mummie obviously feeling the strain.”11

Churchill adamantly refused to cede strategic direction of Britain’s war effort, despite criticism in the press. He insisted, “It is most important that at the summit there should be one mind playing over the whole field, faithfully aided and corrected, but not divided in its integrity.” To this principle of high command in formulating and executing Britain’s strategy he adhered unwaveringly. He threatened that he would not “remain Prime Minister for an hour” if forced to give up his leadership role in directing overall strategy of the war. This threat to resign, he recalled, “repelled all challenges” to his leadership, because no one on the British political scene appeared as able and popular to lead the country in war.12

It was not just threats to resign, however, that secured Churchill’s position of leadership. He provided a realistic appraisal of Britain’s predicament and, despite defeats, offered a path forward to victory. “His speech was a remarkable performance,” his daughter Mary recorded. “Measured—exact—reasoned— dignified—& throughout an undertone of unalterable determination & sober hopefulness.”13 The vote in the House overwhelmingly supported the government by 475 to 25. Still, critics among the ranks of the Conservative party feared, “Once more Churchill has triumphed and he will presumably lead us on to our doom. Always wrong about everything…words, words, follies—foolishness—why has England so taken him to her heart—hasn’t she?”14

The British people took Churchill to heart because he stood out among those around him. He was incomparable as a leader. Churchill knew that “words” matter in a democracy. He justified his decisions in detail and with thoughtful analysis. The British people listened and were convinced: they understood that war carried risks and costs. Britain faced dangerous adversaries who held the initiative. Churchill also inspired others to fight on through disappointment and adversity. The task at hand, he explained, was to hold the ring in the face of powerful blows from the enemy as the tide of war was turning to favor the Grand Alliance. Churchill and Britain would survive the Japanese onslaught.

The Hinge Turns

At the border of India, the Japanese armed forces reached a strategic culminating point from which they could advance no further. What explains Japan’s inability to continue raining down shattering blows and driving on the offensive against the British empire? First, the Japanese army suffered from over-extension. Almost two-thirds of the Japanese army’s ground forces and half its air units were tied down fighting against the Chinese nationalist regime led by Chiang Kai-shek. While the Japanese army scored repeated successes on the battlefield in the fighting on the Chinese mainland, they could not break the will of Chiang’s regime to fight on. In addition, the new conquests in Asia spread out the Japanese army from the border of India to the jungles of New Guinea. The overextended Japanese army lacked the forces to stay on the offensive by invading India or Australia.

Second, American offensive actions drew Japan’s leaders to turn their attention to the Pacific and away from South Asia and Australia. The Doolittle bombing raid on the Japanese homeland stung Japan’s naval leaders to turn their attention to the task of bringing to battle and destroying the American force of aircraft carriers, which had escaped the strike on Pearl Harbor. At the Battle of Midway, the United States wrested the strategic initiative in the war at sea by sinking four Japanese aircraft carriers. Quick to capitalize on the Japanese defeat at Midway, American forces landed on Guadalcanal, and General MacArthur attacked out of Australia into New Guinea. Both offensives met tough resistance and suffered heavy losses, but they succeeded in moving forward and inflicting even heavier casualties on the Japanese. The tide had turned in the Pacific War. Japan’s opening bid for victory had stalled, and Japanese forces were in retreat, beaten back by determined American offensives.

It was Churchill’s lot to lead Britain during the opening stages of the world war when British arms suffered defeats in the struggle against Germany and Japan. Beating back the conquests and bringing about the downfall of the German and Japanese regimes, Churchill knew, hinged upon enlisting the fighting power of the United States. A lesson Churchill learned from the First World War was that “the Allies would have been beaten if America had not come in.”15

In these desperate contests, the British Empire could hold the line and buy time for the United States to mobilize for war. Britain, however, lacked the strength to roll back the initial victories won by Germany and Japan, let alone topple the German and Japanese regimes. Only the massive deployment of American military power overseas from the New World to the Old could accomplish that ambitious aim. This appreciation of America’s importance in the global balance of power guided Churchill’s strategy in both world wars. While Churchill could not prevent the initial defeats suffered by Britain in Asia and the Pacific, he did know that the tide had turned in the unrelenting struggle and the war was won once “the United States, united as never before, have drawn the sword for freedom and cast away the scabbard.”16

Endnotes

1. John Gunther, Inside Asia (New York: Harper, 1939), p. X.

2. Tōto Ishimaru, Japan Must Fight Britain (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1936), pp. 104 and 279.

3. Winston S. Churchill, “Germany and Japan,” 27 November 1936, in Step by Step (New York: Putnam’s, 1939), pp. 65–66.

4. Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War, vol. 3, The Grand Alliance (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950), pp. 606 and 608.

5. Churchill, Grand Alliance, p. 620.

6. Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War, vol. 4, The Hinge of Fate (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950), p. 100.

7. Churchill address, “War Situation,” House of Commons, 27 January 1942, accessed at https://hansard.parliament.uk/ Commons/1942-01-27/debates/ d6c63f66-e4ea-4ba4-8958- 3ad126eaa503/WarSituation.

8. Churchill address, “War Situation.”

9. Robert Rhodes James, ed., Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches, vol. 3, 1914–1922 (London: Chelsea House Publishers, 1974), p. 2258.

10. Churchill address, “War Situation.”

11. Emma Soames, ed., Mary Churchill’s War: The Wartime Diaries of Churchill’s Youngest Daughter (London: Two Roads, 2021), p. 150.

12. Churchill, Hinge of Fate, p. 91.

13. Soames, ed., Mary Churchill’s War, p. 151.

14. Simon Heffer, ed., Henry “Chips” Channon: The Diaries, vol. 2, 1938–43 (London: Hutchinson, 2021), p. 817.

15. Admiral William S. Sims recorded Churchill’s comments about the war situation in a letter to his wife, 10 May 1917, Sims Papers, box 9, Library of Congress.

16. Winston S. Churchill, Speech before a Joint Session of Congress on 26 December 1941, https://winstonchurchill.org/ old-site/learn/speeches-learn/u-scongress-december-1941/

Subscribe

WANT MORE?

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.